Culture of Ireland

Culture Name

Irish

Alternative Names

Na hÉireanneach; Na Gaeil

Orientation

Identification. The Republic of Ireland (Poblacht na hÉireann in Irish, although commonly referred to as Éire, or Ireland) occupies five-sixths of the island of Ireland, the second largest island of the British Isles. Irish is the common term of reference for the country's citizens, its national culture, and its national language. While Irish national culture is relatively homogeneous when compared to multinational and multicultural states elsewhere, Irish people recognize both some minor and some significant cultural distinctions that are internal to the country and to the island. In 1922 Ireland, which until then had been part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, was politically divided into the Irish Free State (later the Republic of Ireland) and Northern Ireland, which continued as part of the renamed United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland occupies the remaining sixth of the island. Almost eighty years of separation have resulted in diverging patterns of national cultural development between these two neighbors, as seen in language and dialect, religion, government and politics, sport, music, and business culture. Nevertheless, the largest minority population in Northern Ireland (approximately 42 percent of the total population of 1.66 million) consider themselves to be nationally and ethnically Irish, and they point to the similarities between their national culture and that of the Republic as one reason why they, and Northern Ireland, should be reunited with the Republic, in what would then constitute an all-island nation-state. The majority population in Northern Ireland, who consider themselves to be nationally British, and who identify with the political communities of Unionism and Loyalism, do not seek unification with Ireland, but rather wish to maintain their traditional ties to Britain.

Within the Republic, cultural distinctions are recognized between urban and rural areas (especially between the capital city Dublin and the rest of the country), and between regional cultures, which are most often discussed in terms of the West, the South, the Midlands, and the North, and which correspond roughly to the traditional Irish provinces of Connacht, Munster, Leinster, and Ulster, respectively. While the overwhelming majority of Irish people consider themselves to be ethnically Irish, some Irish nationals see themselves as Irish of British descent, a group sometimes referred to as the "Anglo-Irish" or "West Britons." Another important cultural minority are Irish "Travellers," who have historically been an itinerant ethnic group known for their roles in the informal economy as artisans, traders, and entertainers. There are also small religious minorities (such as Irish Jews), and ethnic minorities (such as Chinese, Indians, and Pakistanis), who have retained many aspects of cultural identification with their original national cultures.

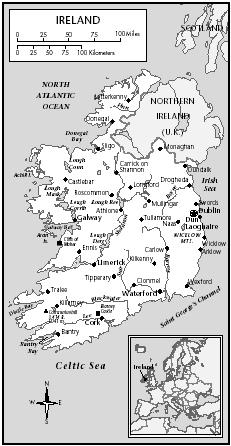

Location and Geography. Ireland is in the far west of Europe, in the North Atlantic Ocean, west of the island of Great Britain. The island is 302 miles (486 kilometers) long, north to south, and 174 miles (280 kilometers) at its widest point. The area of the island is 32,599 square miles (84,431 square kilometers), of which the Republic covers 27, 136 square miles (70,280 square kilometers). The Republic has 223 miles (360 kilometers) of land border, all with the United Kingdom, and 898 miles (1,448 kilometers) of coastline. It is separated from its neighboring island of Great Britain to the east by the Irish Sea, the North Channel, and Saint George's Channel. The climate is temperate maritime, modified by the North Atlantic Current. Ireland has mild

Ireland

winters and cool summers. Because of the high precipitation, the climate is consistently humid. The Republic is marked by a low-lying fertile central plain surrounded by hills and uncultivated small mountains around the outer rim of the island. Its high point is 3,414 feet (1,041 meters). The largest river is the Shannon, which rises in the northern hills and flows south and west into the Atlantic. The capital city, Dublin (Baile Átha Cliath in Irish), at the mouth of the River Liffey in central eastern Ireland, on the original site of a Viking settlement, is currently home to almost 40 percent of the Irish population; it served as the capital of Ireland before and during Ireland's integration within the United Kingdom. As a result, Dublin has long been noted as the center of the oldest Anglophone and British-oriented area of Ireland; the region around the city has been known as the "English Pale" since medieval times.

Demography. The population of the Republic of Ireland was 3,626,087 in 1996, an increase of 100,368 since the 1991 census. The Irish population has increased slowly since the drop in population that occurred in the 1920s. This rise in population is expected to continue as the birthrate has steadily increased while the death rate has steadily decreased. Life expectancy for males and females born in 1991 was 72.3 and 77.9, respectively (these figures for 1926 were 57.4 and 57.9, respectively). The national population in 1996 was relatively young: 1,016,000 people were in the 25–44 age group, and 1,492,000 people were younger than 25. The greater Dublin area had 953,000 people in 1996, while Cork, the nation's second largest city, was home to 180,000. Although Ireland is known worldwide for its rural scenery and lifestyle, in 1996 1,611,000 of its people lived in its 21 most populated cities and towns, and 59 percent of the population lived in urban areas of one thousand people or more. The population density in 1996 was 135 per square mile (52 per square kilometer).

Linguistic Affiliation. Irish (Gaelic) and English are the two official languages of Ireland. Irish is a Celtic (Indo-European) language, part of the Goidelic branch of insular Celtic (as are Scottish Gaelic and Manx). Irish evolved from the language brought to the island in the Celtic migrations between the sixth and the second century B.C.E. Despite hundreds of years of Norse and Anglo-Norman migration, by the sixteenth century Irish was the vernacular for almost all of the population of Ireland. The subsequent Tudor and Stuart conquests and plantations (1534–1610), the Cromwellian settlement (1654), the Williamite war (1689–1691), and the enactment of the Penal Laws (1695) began the long process of the subversion of the language. Nevertheless, in 1835 there were four million Irish speakers in Ireland, a number that was severely reduced in the Great Famine of the late 1840s. By 1891 there were only 680,000 Irish speakers, but the key role that the Irish language played in the development of Irish nationalism in the nineteenth century, as well as its symbolic importance in the new Irish state of the twentieth century, have not been enough to reverse the process of vernacular language shift from Irish to English. In the 1991 census, in those few areas where Irish remains the vernacular, and which are officially defined as the Gaeltacht , there were only 56,469 Irish-speakers. Most primary and secondary school students in Ireland study Irish, however, and it remains an important means of communication in governmental, educational, literary, sports, and cultural circles beyond the Gaeltacht. (In the 1991 census, almost 1.1 million Irish people claimed to be Irish-speaking, but this number does not distinguish levels of fluency and usage.)

Irish is one of the preeminent symbols of the Irish state and nation, but by the start of the twentieth century English had supplanted Irish as the vernacular language, and all but a very few ethnic Irish are fluent in English. Hiberno-English (the English language spoken in Ireland) has been a strong influence in the evolution of British and Irish literature, poetry, theater, and education since the end of the nineteenth century. The language has also been an important symbol to the Irish national minority in Northern Ireland, where despite many social and political impediments its use has been slowly increasing since the return of armed conflict there in 1969.

Symbolism. The flag of Ireland has three equal vertical bands of green (hoist side), white, and orange. This tricolor is also the symbol of the Irish nation in other countries, most notably in Northern Ireland among the Irish national minority. Other flags that are meaningful to the Irish include the golden harp on a green background and the Dublin workers' flag of "The Plough and the Stars." The harp is the principal symbol on the national coat of arms, and the badge of the Irish state is the shamrock. Many symbols of Irish national identity derive in part from their association with religion and church. The shamrock clover is associated with Ireland's patron Saint Patrick, and with the Holy Trinity of Christian belief. A Saint Brigid's cross is often found over the entrance to homes, as are representations of saints and other holy people, as well as portraits of the greatly admired, such as Pope John XXIII and John F. Kennedy.

Green is the color associated worldwide with Irishness, but within Ireland, and especially in Northern Ireland, it is more closely associated with being both Irish and Roman Catholic, whereas orange is the color associated with Protestantism, and more especially with Northern Irish people who support Loyalism to the British crown and continued union with Great Britain. The colors of red, white, and blue, those of the British Union Jack, are often used to mark the territory of Loyalist communities in Northern Ireland, just as orange, white, and green mark Irish Nationalist territory there. Sports, especially the national ones organized by the Gaelic Athletic Association such as hurling, camogie, and Gaelic football, also serve as central symbols of the nation.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. The nation that evolved in Ireland was formed over two millennia, the result of diverse forces both internal and external to the island. While there were a number of groups of people living on the island in prehistory, the Celtic migrations of the first millennium B.C.E. brought the language and many aspects of Gaelic society that have figured so prominently in more recent nationalist revivals. Christianity was introduced in the fifth century C.E. , and from its beginning Irish Christianity has been associated with monasticism. Irish monks did much to preserve European Christian heritage before and during the Middle Ages, and they ranged throughout the continent in their efforts to establish their holy orders and serve their God and church.

From the early ninth century Norsemen raided Ireland's monasteries and settlements, and by the next century they had established their own coastal communities and trading centers. The traditional Irish political system, based on five provinces (Meath, Connacht, Munster, Leinster, and Ulster), assimilated many Norse people, as well as many of the Norman invaders from England after 1169. Over the next four centuries, although the Anglo-Normans succeeded in controlling most of the island, thereby establishing feudalism and their structures of parliament, law, and administration, they also adopted the Irish language and customs, and intermarriage between Norman and Irish elites had become common. By the end of the fifteenth century, the Gaelicization of the Normans had resulted in only the Pale, around Dublin, being controlled by English lords.

In the sixteenth century, the Tudors sought to reestablish English control over much of the island. The efforts of Henry VIII to disestablish the Catholic Church in Ireland began the long association between Irish Catholicism and Irish nationalism. His daughter, Elizabeth I, accomplished the English conquest of the island. In the early seventeenth century the English government began a policy of colonization by importing English and Scottish immigrants, a policy that often necessitated the forcible removal of the native Irish. Today's nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland has its historical roots in this period,

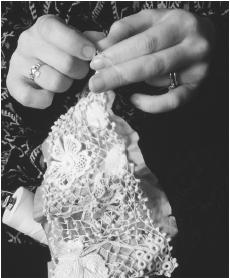

A woman makes clones knots between the main motifs in a piece of hand-crochet.

when New English Protestants and Scottish Presbyterians moved into Ulster. William of Orange's victory over the Stuarts at the end of the seventeenth century led to the period of the Protestant Ascendancy, in which the civil and human rights of the native Irish, the vast majority of whom were Catholics, were repressed. By the end of the eighteenth century the cultural roots of the nation were strong, having grown through a mixture of Irish, Norse, Norman, and English language and customs, and were a product of English conquest, the forced introduction of colonists with different national backgrounds and religions, and the development of an Irish identity that was all but inseparable from Catholicism.

National Identity. The long history of modern Irish revolutions began in 1798, when Catholic and Presbyterian leaders, influenced by the American and French Revolutions and desirous of the introduction of some measure of Irish national self-government, joined together to use force to attempt to break the link between Ireland and England. This, and subsequent rebellions in 1803, 1848, and 1867, failed. Ireland was made part of the United Kingdom in the Act of Union of 1801, which lasted until the end of World War I (1914–1918), when the Irish War of Independence led to a compromise agreement between the Irish belligerents, the British government, and Northern Irish Protestants who wanted Ulster to remain part of the United Kingdom. This compromise established the Irish Free State, which was composed of twenty-six of Ireland's thirty-two counties. The remainder became Northern Ireland, the only part of Ireland to stay in the United Kingdom, and wherein the majority population were Protestant and Unionist.

The cultural nationalism that succeeded in gaining Ireland's independence had its origin in the Catholic emancipation movement of the early nineteenth century, but it was galvanized by Anglo-Irish and other leaders who sought to use the revitalization of Irish language, sport, literature, drama, and poetry to demonstrate the cultural and historical bases of the Irish nation. This Gaelic Revival stimulated great popular support for both the idea of the Irish nation, and for diverse groups who sought various ways of expressing this modern nationalism. The intellectual life of Ireland began to have a great impact throughout the British Isles and beyond, most notably among the Irish Diaspora who had been forced to flee the disease, starvation, and death of the Great Famine of 1846–1849, when a blight destroyed the potato crop, upon which the Irish peasantry depended for food. Estimates vary, but this famine period resulted in approximately one million dead and two million emigrants.

By the end of the nineteenth century many Irish at home and abroad were committed to the peaceful attainment of "Home Rule" with a separate Irish parliament within the United Kingdom while many others were committed to the violent severing of Irish and British ties. Secret societies, forerunners of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), joined with public groups, such as trade union organizations, to plan another rebellion, which took place on Easter Monday, 24 April 1916. The ruthlessness that the British government displayed in putting down this insurrection led to the wide-scale disenchantment of the Irish people with Britain. The Irish War of Independence (1919–1921), followed by the Irish Civil War (1921–1923), ended with the creation of an independent state.

Ethnic Relations. Many countries in the world have sizable Irish ethnic minorities, including the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Argentina. While many of these people descend from emigrants of the mid- to late nineteenth century, many others are descendants of more recent Irish emigrants, while still others were born in Ireland. These ethnic communities identify in varying degrees with Irish culture, and they are distinguished by their religion, dance, music, dress, food, and secular and religious celebrations (the most famous of which is the Saint Patrick Day's parades that are held in Irish communities around the world on 17 March).

While Irish immigrants often suffered from religious, ethnic, and racial bigotry in the nineteenth century, their communities today are characterized by both the resilience of their ethnic identities and the degree to which they have assimilated to host national cultures. Ties to the "old country" remain strong. Many people of Irish descent worldwide have been active in seeking a solution to the national conflict in Northern Ireland, known as the "Troubles."

Ethnic relations in the Republic of Ireland are relatively peaceful, given the homogeneity of national culture, but Irish Travellers have often been the victims of prejudice. In Northern Ireland the level of ethnic conflict, which is inextricably linked to the province's bifurcation of religion, nationalism, and ethnic identity, is high, and has been since the outbreak of political violence in 1969. Since 1994 there has been a shaky and intermittent cease-fire among the paramilitary groups in Northern Ireland. The 1998 Good Friday agreement is the most recent accord.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

The public architecture of Ireland reflects the country's past role in the British Empire, as most Irish cities and towns were either designed or remodeled as Ireland evolved with Britain. Since independence, much of the architectural iconography and symbolism, in terms of statues, monuments, museums, and landscaping, has reflected the sacrifices of those who fought for Irish freedom. Residential and business architecture is similar to that found elsewhere in the British Isles and Northern Europe.

The Irish put great emphasis on nuclear families establishing residences independent of the residences of the families from which the husband and wife hail, with the intention of owning these residences; Ireland has a very high percentage of owner-occupiers. As a result, the suburbanization of Dublin is resulting in a number of social, economic, transportation, architectural, and legal problems that Ireland must solve in the near future.

The informality of Irish culture, which is one thing that Irish people believe sets them apart from British people, facilitates an open and fluid approach between people in public and private spaces. Personal space is small and negotiable; while it is not common for Irish people to touch each other when walking or talking, there is no prohibition on public displays of emotion, affection, or attachment. Humor, literacy, and verbal acuity are valued; sarcasm and humor are the preferred sanctions if a person transgresses the few rules that govern public social interaction.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. The Irish diet is similar to that of other Northern European nations. There is an emphasis on the consumption of meat, cereals, bread, and potatoes at most meals. Vegetables such as cabbage, turnips, carrots, and broccoli are also popular as accompaniments to the meat and potatoes. Traditional Irish daily eating habits, influenced by a farming ethos, involved four meals: breakfast, dinner (the midday meal and the main one of the day), tea (in early evening, and distinct from "high tea" which is normally served at 4:00 P.M. and is associated with British customs), and supper (a light repast before retiring). Roasts and stews, of lamb, beef, chicken, ham, pork, and turkey, are the centerpieces of traditional meals. Fish, especially salmon, and seafood, especially prawns, are also popular meals. Until recently, most shops closed at the dinner hour (between 1:00 and 2:00 P.M. ) to allow staff to return home for their meal. These patterns, however, are changing, because of the growing importance of new lifestyles, professions, and patterns of work, as well as the increased consumption of frozen, ethnic, take-out, and processed foods. Nevertheless, some foods (such as wheaten breads, sausages, and bacon rashers) and some drinks (such as the national beer, Guinness, and Irish whiskey) maintain their important gustatory and symbolic roles in Irish meals and socializing. Regional dishes, consisting of variants on stews, potato casseroles, and breads, also exist. The public house is an essential meeting place for all Irish communities, but these establishments traditionally seldom served dinner. In the past pubs had two separate sections, that of the bar, reserved for males, and the lounge, open to men and women. This distinction is eroding, as are expectations of gender preference in the consumption of alcohol.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. There are few ceremonial food customs. Large family gatherings often sit down to a main meal of roast chicken and ham, and turkey is becoming the preferred dish for Christmas (followed by Christmas cake or plum pudding). Drinking behavior in pubs

The informality of Irish culture facilitates an open and fluid approach between people in public places.

is ordered informally, in what is perceived by some to be a ritualistic manner of buying drinks in rounds.

Basic Economy. Agriculture is no longer the principal economic activity. Industry accounts for 38 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) and 80 percent of exports, and employs 27 percent of the workforce. During the 1990s Ireland enjoyed annual trade surpluses, falling inflation, and increases in construction, consumer spending, and business and consumer investment. Unemployment was down (from 12 percent in 1995 to around 7 percent in 1999) and emigration declined. As of 1998, the labor force consisted of 1.54 million people; as of 1996, 62 percent of the labor force was in services, 27 percent in manufacturing and construction, and 10 percent in agriculture, forestry, and fishing. In 1999 Ireland had the fastest growing economy in the European Union. In the five years to 1999 GDP per capita rose by 60 percent, to approximately $22,000 (U.S.).

Despite its industrialization, Ireland still is an agricultural country, which is important to its self-image and its image for tourists. As of 1993, only 13 percent of its land was arable, while 68 percent was devoted to permanent pastures. While all Irish food producers consume a modest amount of their product, agriculture and fishing are modern, mechanized, and commercial enterprises, with the vast bulk of production going to the national and international markets. Although the image of the small-holding subsistence farmer persists in art, literary, and academic circles, Irish farming and farmers are as advanced in technology and technique as most of their European neighbors. Poverty persists, however, among farmers with small holdings, on poor land, particularly in many parts of the west and south. These farmers, who to survive must rely more on subsistence crops and mixed farming than do their more commercial neighbors, involve all family members in a variety of economic strategies. These activities include off-farm wage labor and the acquisition of state pensions and unemployment benefits ("the dole").

Land Tenure and Property. Ireland was one of the first countries in Europe in which peasants could purchase their landholdings. Today all but a very few farms are family-owned, although some mountain pasture and bog lands are held in common. Cooperatives are principally production and marketing enterprises. An annually changing proportion of pasture and arable land is leased out each year, usually for an eleven-month period, in a traditional system known as conacre.

Major Industries. The main industries are food products, brewing, textiles, clothing, and pharmaceuticals, and Ireland is fast becoming known for its roles in the development and design of information technologies and financial support services. In agriculture the main products are meat and dairy, potatoes, sugar beets, barley, wheat, and turnips. The fishing industry concentrates on cod, haddock, herring, mackerel, and shellfish (crab and lobster). Tourism increases its share of the economy annually; in 1998 total tourism and travel earnings were $3.1 billion (U.S.).

Trade. Ireland had a consistent trade surplus at the end of the 1990s. In 1997 this surplus amounted to $13 billion (U.S). Ireland's main trading partners are the United Kingdom, the rest of the European Union, and the United States.

Division of Labor. In farming, daily and seasonal tasks are divided according to age and gender. Most public activities that deal with farm production are handled by adult males, although some agricultural production associated with the domestic household, such as eggs and honey, are marketed by adult females. Neighbors often help each other with their labor or equipment when seasonal production demands, and this network of local support is sustained through ties of marriage, religion and church, education, political party, and sports. While in the past most blue-collar and wage-labor jobs were held by males, women have increasingly entered the workforce over the last generation, especially in tourism, sales, and information and financial services. Wages and salaries are consistently lower for women, and employment in the tourism industry is often seasonal or temporary. There are very few legal age or gender restrictions to entering professions, but here too men dominate in numbers if not also in influence and control. Irish economic policy has encouraged foreign-owned businesses, as one way to inject capital into underdeveloped parts of the country. The United States and the United Kingdom top the list of foreign investors in Ireland.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. The Irish often perceive that their culture is set off from their neighbors by its egalitarianism, reciprocity, and informality, wherein strangers do not wait for introductions to converse, the first name is quickly adopted in business and professional discourse, and the sharing of food, tools, and other valuables is commonplace. These leveling mechanisms alleviate many pressures engendered by class relations, and often belie rather strong divisions of status, prestige, class, and national identity. While the rigid class structure for which the English are renowned is largely absent, social and economic class distinctions exist, and are often reproduced through educational and religious institutions, and the professions. The old British and Anglo-Irish aristocracy are small in number and relatively powerless. They have been replaced at the apex of Irish society by the wealthy, many of whom have made their fortunes in business and professions, and by celebrities from the arts and sports worlds. Social classes are discussed in terms of working class, middle class, and gentry, with certain occupations, such as farmers, often categorized according to their wealth, such as large and small farmers, grouped according to the size of their landholding and capital. The social boundaries between these groups are often indistinct and permeable, but their basic dimensions are clearly discernible to locals through dress, language, conspicuous consumption, leisure activities, social networks, and occupation and profession. Relative wealth and social class also influence life choices, perhaps the most important being that of primary and secondary school, and university, which in turn affects one's class mobility. Some minority groups, such as Travellers, are often portrayed in popular culture as being outside or beneath the accepted social class system, making escape from the underclass as difficult for them as for the long-term unemployed of the inner cities.

Symbols of Social Stratification. Use of language, especially dialect, is a clear indicator of class and other social standing. Dress codes have relaxed over the last generation, but the conspicuous consumption of important symbols of wealth and success, such as designer clothing, good food, travel, and expensive cars and houses, provides important strategies for class mobility and social advancement.

Political Life

Government. The Republic of Ireland is a parliamentary democracy. The National Parliament ( Oireachtas ) consists of the president (directly elected by the people), and two houses: Dáil Éireann (House of Representatives) and Seanad Éireann (Senate). Their powers and functions derive from the constitution (enacted 1 July 1937). Representatives to Dáil Éireann, who are called Teachta Dála , or TDs, are elected through proportional representation with a single transferable vote. While legislative

People walk past a colorful storefront in Dublin.

power is vested in the Oireachtas, all laws are subject to the obligations of European Community membership, which Ireland joined in 1973. The executive power of the state is vested in the government, composed of the Taoiseach (prime minister) and the cabinet. While a number of political parties are represented in the Oireachtas, governments since the 1930s have been led by either the Fianna Fáil or the Fine Gael party, both of which are center-right parties. County Councils are the principal form of local government, but they have few powers in what is one of the most centralized states in Europe.

Leadership and Political Officials. Irish political culture is marked by its postcolonialism, conservatism, localism, and familism, all of which were influenced by the Irish Catholic Church, British institutions and politics, and Gaelic culture. Irish political leaders must rely on their local political support—which depends more on their roles in local society, and their real or imagined roles in networks of patrons and clients—than it does on their roles as legislators or political administrators. As a result there is no set career path to political prominence, but over the years sports heroes, family members of past politicians, publicans, and military people have had great success in being elected to the Oireachtas. Pervasive in Irish politics is admiration and political support for politicians who can provide pork barrel government services and supplies to his constituents (very few Irish women reach the higher levels of politics, industry, and academia). While there has always been a vocal left in Irish politics, especially in the cities, since the 1920s these parties have seldom been strong, with the occasional success of the Labour Party being the most notable exception. Most Irish political parties do not provide clear and distinct policy differences, and few espouse the political ideologies that characterize other European nations. The major political division is that between Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, the two largest parties, whose support still derives from the descendants of the two opposing sides in the Civil War, which was fought over whether to accept the compromise treaty that divided the island into the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland. As a result, the electorate does not vote for candidates because of their policy initiatives, but because of a candidate's personal skill in achieving material gain for constituents, and because the voter's family has traditionally supported the candidate's party. This voting pattern depends on local knowledge of the politician, and the informality of local culture, which encourages people to believe that they have direct access to their politicians. Most national and local politicians have regular open office hours where constituents can discuss their problems and concerns without having to make an appointment.

Social Problems and Control. The legal system is based on common law, modified by subsequent legislation and the constitution of 1937. Judicial review of legislation is made by the Supreme Court, which is appointed by the president of Ireland on the advice of the government. Ireland has a long history of political violence, which is still an important aspect of life in Northern Ireland, where paramilitary groups such as the IRA have enjoyed some support from people in the Republic. Under emergency powers acts, certain legal rights and protections can be suspended by the state in the pursuit of terrorists. Crimes of nonpolitical violence are rare, though some, such as spousal and child abuse, may go unreported. Most major crimes, and the crimes most important in popular culture, are those of burglary, theft, larceny, and corruption. Crime rates are higher in urban areas, which in some views results from the poverty endemic to some inner cities. There is a general respect for the law and its agents, but other social controls also exist to sustain moral order. Such institutions as the Catholic Church and the state education system are partly responsible for the overall adherence to rules and respect for authority, but there is an anarchic quality to Irish culture that sets it off from its neighboring British cultures. Interpersonal forms of informal social control include a heightened sense of humor and sarcasm, supported by the general Irish values of reciprocity, irony, and skepticism regarding social hierarchies.

Military Activity. The Irish Defence Forces have army, naval service and air corps branches. The total membership of the permanent forces is approximately 11,800, with 15,000 serving in the reserves. While the military is principally trained to defend Ireland, Irish soldiers have served in most United Nations peacekeeping missions, in part because of Ireland's policy of neutrality. The Defence Forces play an important security role on the border with Northern Ireland. The Irish National Police, An Garda Siochána , is an unarmed force of approximately 10,500 members.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

The national social welfare system mixes social insurance and social assistance programs to provide financial support to the ill, the aged, and the unemployed, benefitting roughly 1.3 million people. State spending on social welfare comprises 25 percent of government expenditures, and about 6 percent of GDP. Other relief agencies, many of which are connected to the churches, also provide valuable financial assistance and social relief programs for the amelioration of the conditions of poverty and inequity.

Nongvernmental Organizations and Other Associations

Civil society is well-developed, and nongovernmental organizations serve all classes, professions, regions, occupations, ethnic groups, and charitable causes. Some are very powerful, such as the Irish Farmers Association, while others, such as the international charitable support organization, Trócaire , a Catholic agency for world development, command widespread financial and moral support. Ireland is one of the highest per capita contributors to private international aid in the world. Since the creation of the Irish state a number of development agencies and utilities have been organized in partly state-owned bodies, such as the Industrial Development Agency, but these are slowly being privatized.

Gender Roles and Statuses

While gender equality in the workplace is guaranteed by law, remarkable inequities exist between the genders in such areas as pay, access to professional achievement, and parity of esteem in the workplace. Certain jobs and professions are still considered by large segments of the population to be gender linked. Some critics charge that gender biases continue to be established and reinforced in the nation's major institutions of government, education, and religion. Feminism is a growing movement in rural and urban areas, but it still faces many obstacles among traditionalists.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Marriages are seldom arranged in modern Ireland. Monogamous marriages are the norm, as supported and sanctioned by the state and the Christian churches. Divorce has been legal since 1995. Most spouses are selected through the expected means of individual trial and error that have become the norm in Western European society. The demands of farm society and economy still place great pressure on rural men and women to marry, especially in some relatively poor rural districts where there is a high migration rate among

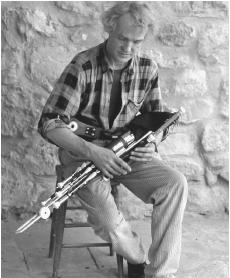

Eugene Lamb, an uillean pipe maker in Kinvara, County Galway, holds one of his wares.

women, who go to the cities or emigrate in search of employment and social standing commensurate with their education and social expectations. Marriage festivals for farm men and women, the most famous of which takes place in the early autumn in Lisdoonvarna, has served as one way to bring people together for possible marriage matches, but the increased criticism of such practices in Irish society may endanger their future. The estimated marriage rate per thousand people in 1998 was 4.5. While the average ages of partners at marriage continues to be older than other Western societies, the ages have dropped over the last generation.

Domestic Unit. The nuclear family household is the principal domestic unit, as well as the basic unit of production, consumption, and inheritance in Irish society.

Inheritance. Past rural practices of leaving the patrimony to one son, thereby forcing his siblings into wage labor, the church, the army, or emigration, have been modified by changes in Irish law, gender roles, and the size and structure of families. All children have legal rights to inheritance, although a preference still lingers for farmers' sons to inherit the land, and for a farm to be passed on without division. Similar patterns exist in urban areas, where gender and class are important determinants of the inheritance of property and capital.

Kin Groups. The main kin group is the nuclear family, but extended families and kindreds continue to play important roles in Irish life. Descent is from both parents' families. Children in general adopt their father's surnames. Christian (first) names are often selected to honor an ancestor (most commonly, a grandparent), and in the Catholic tradition most first names are those of saints. Many families continue to use the Irish form of their names (some "Christian" names are in fact pre-Christian and untranslatable into English). Children in the national primary school system are taught to know and use the Irish language equivalent of their names, and it is legal to use your name in either of the two official languages.

Socialization

Child Rearing and Education. Socialization takes place in the domestic unit, in schools, at church, through the electronic and print media, and in voluntary youth organizations. Particular emphasis is placed on education and literacy; 98 percent of the population aged fifteen and over can read and write. The majority of four-year-olds attend nursery school, and all five-year-olds are in primary school. More than three thousand primary schools serve 500,000 children. Most primary schools are linked to the Catholic Church, and receive capital funding from the state, which also pays most teachers' salaries. Post-primary education involves 370,000 students, in secondary, vocational, community, and comprehensive schools.

Higher Education. Third-level education includes universities, technological colleges, and education colleges. All are self-governing, but are principally funded by the state. About 50 percent of youth attend some form of third-level education, half of whom pursue degrees. Ireland is world famous for its universities, which are the University of Dublin (Trinity College), the National University of Ireland, the University of Limerick, and Dublin City University.

Etiquette

General rules of social etiquette apply across ethnic, class, and religious barriers. Loud, boisterous, and boastful behavior are discouraged. Unacquainted people look directly at each other in public spaces, and often say "hello" in greeting. Outside of formal introductions greetings are often vocal and are not accompanied by a handshake or kiss. Individuals maintain a public personal space around themselves; public touching is rare. Generosity and reciprocity are key values in social exchange, especially in the ritualized forms of group drinking in pubs.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. The Irish Constitution guarantees freedom of conscience and the free profession and practice of religion. There is no official state religion, but critics point to the special consideration given to the Catholic Church and its agents since the inception of the state. In the 1991 census 92 percent of the population were Roman Catholic, 2.4 percent belonged to the Church of Ireland (Anglican), 0.4 percent were Presbyterians, and 0.1 percent were Methodists. The Jewish community comprised .04 percent of the total, while approximately 3 percent belonged to other religious groups. No information on religion was returned for 2.4 percent of the population. Christian revivalism is changing many of the ways in which the people relate to each other and to their formal church institutions. Folk cultural beliefs also survive, as evidenced in the many holy and healing places, such as the holy wells that dot the landscape.

Religious Practitioners. The Catholic Church has four ecclesiastical provinces, which encompass the whole island, thus crossing the boundary with Northern Ireland. The Archbishop of Armagh in Northern Ireland is the Primate of All Ireland. The diocesan structure, in which thirteen hundred parishes are served by four thousand priests, dates to the twelfth century and does not coincide with political boundaries. There are approximately twenty thousand people serving in various Catholic religious orders, out of a combined Ireland and Northern Ireland Catholic population of 3.9 million. The Church of Ireland, which has twelve dioceses, is an autonomous church within the worldwide Anglican Communion. Its Primate of All Ireland is the Archbishop of Armagh, and its total membership is 380,000, 75 percent of whom are in Northern Ireland. There are 312,000 Presbyterians on the island (95 percent of whom are in Northern Ireland), grouped into 562 congregations and twenty-one presbyteries.

Rituals and Holy Places. In this predominantly Catholic country there are a number of Church-recognized shrines and holy places, most notably that of Knock, in County Mayo, the site of a reported apparition of the Blessed Mother. Traditional holy places, such as holy wells, attract local people at all times of the year, although many are associated with particular days, saints, rituals, and feasts. Internal pilgrimages to such places as Knock and Croagh Patrick (a mountain in County Mayo associated with Saint Patrick) are important aspects of Catholic belief, which often reflect the integration of formal and traditional religious practices. The holy days of the official Irish Catholic Church calendar are observed as national holidays.

Death and the Afterlife. Funerary customs are inextricably linked to various Catholic Church religious rituals. While wakes continue to be held in homes, the practice of utilizing funeral directors and parlors is gaining in popularity.

Medicine and Health Care

Medical services are provided free of charge by the state to approximately a third of the population. All others pay minimal charges at public health facilities. There are roughly 128 doctors for every 100,000 people. Various forms of folk and alternative medicines exist throughout the island; most rural communities have locally known healers or healing places. Religious sites, such as the pilgrimage destination of Knock, and rituals are also known for their healing powers.

Secular Celebrations

The national holidays are linked to national and religious history, such as Saint Patrick's Day, Christmas, and Easter, or are seasonal bank and public holidays which occur on Mondays, allowing for long weekends.

The Arts and Humanities

Literature. The literary renaissance of the late nineteenth century integrated the hundreds-year-old traditions of writing in Irish with those of English, in what has come to be known as Anglo-Irish literature. Some of the greatest writers in English over the last century were Irish: W. B. Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, Frank O'Connor, Seán O'Faoláin, Seán O'Casey, Flann O'Brien, and Seamus Heaney. They and many others have constituted an unsurpassable record of a national experience that has universal appeal.

Graphic Arts. High, popular, and folk arts are highly valued aspects of local life throughout Ireland.

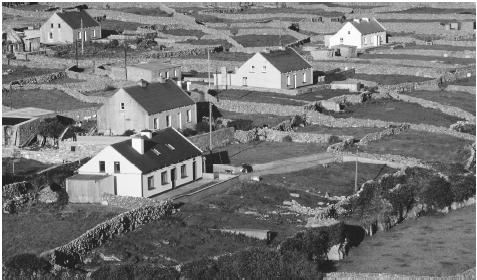

Walls separate individual fields on Inisheer, one of Ireland's Aran Islands.

Graphic and visual arts are strongly supported by the government through its Arts Council and the 1997-formed Department of Arts, Heritage, Gaeltacht, and the Islands. All major international art movements have their Irish representatives, who are often equally inspired by native or traditional motifs. Among the most important artists of the century are Jack B. Yeats and Paul Henry.

Performance Arts. Performers and artists are especially valued members of the Irish nation, which is renowned internationally for the quality of its music, acting, singing, dancing, composing, and writing. U2 and Van Morrison in rock, Daniel O'Donnell in country, James Galway in classical, and the Chieftains in Irish traditional music are but a sampling of the artists who have been important influences on the development of international music. Irish traditional music and dance have also spawned the global phenomenon of Riverdance. Irish cinema celebrated its centenary in 1996. Ireland has been the site and the inspiration for the production of feature films since 1910. Major directors (such as Neill Jordan and Jim Sheridan) and actors (such as Liam Neeson and Stephen Rhea) are part of a national interest in the representation of contemporary Ireland, as symbolized in the state-sponsored Film Institute of Ireland.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

The government is the principal source of financial support for academic research in the physical and social sciences, which are broadly and strongly represented in the nation's universities and in government-sponsored bodies, such as the Economic and Social Research Institute in Dublin. Institutions of higher learning draw relatively high numbers of international students at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels, and Irish researchers are to be found in all areas of academic and applied research throughout the world.

Bibliography

Clancy, Patrick, Sheelagh Drudy, Kathleen Lynch, and Liam O'Dowd, eds. Irish Society: Sociological Perspectives , 1995.

Curtin, Chris, Hastings Donnan, and Thomas M. Wilson, eds. Irish Urban Cultures , 1993.

Taylor, Lawrence J. Occasions of Faith: An Anthropology of Irish Catholics , 1995.

Wilson, Thomas M. "Themes in the Anthropology of Ireland." In Susan Parman, ed., Europe in the Anthropological Imagination , 1998.