Culture of Iceland

Culture Name

Icelandic

Orientation

Identification. Scandinavian sailors discovered Iceland in the mid-ninth century, and the first settler recognized in the literary-historical tradition, Ingólfur Arnason, arrived in 874. The book of settlements ( Landnámabók ), which contains information on four hundred settlers, was compiled in the twelfth century. The story set down there and repeated to this day is that a Norse Viking named Flóki sailed to Iceland, but spent so much energy hunting and fishing that he did not lay up hay for his livestock, which died in the winter, and had to return. He then gave the island its unpromising name.

Among the settlers and the slaves the Scandinavians brought were people of Irish as well as Norse descent; Icelanders still debate the relative weight of the Norse and Irish contributions to their culture and biology. Some date a distinctive sense of "Icelandicness" to the writing of the First Grammatical Treatise in the twelfth century. The first document was a recording of laws in 1117. Many copies and versions of legal books were produced. Compilations of law were called Grágas ("gray goose" or "wild goose").

In 930, a General Assembly was established, and in 1000, Iceland became Christian by a decision of the General Assembly. In 1262–1264, Iceland was incorporated into Norway; in 1380, when Norway came under Danish rule, Iceland went along; and on 17 June 1944, Iceland became an independent republic, though it had gained sovereignty in 1918 and had been largely autonomous since 1904.

The sense of Iceland as a separate state with a separate identity dates from the nineteenth-century nationalist movement. According to the ideology of that movement, all Icelanders share a common heritage and identity, though some argue that economic stratification has resulted in divergent identities and language usage.

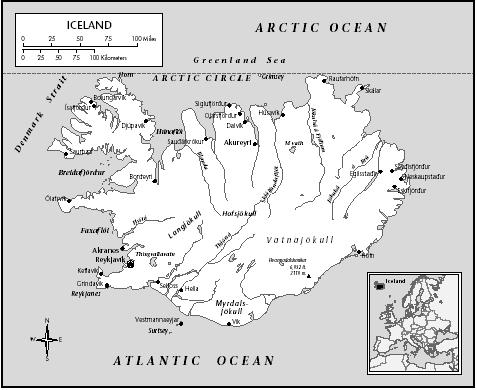

Location and Geography. Iceland is an island in the north Atlantic Ocean between Greenland and Norway just south of the Arctic Circle. It covers 63,860 square miles (103,000 square kilometers), of which about 620 are cultivated, 12,400 are used for grazing, 7,500 are covered by glaciers, 1,900 are covered by lakes, and 41,500 are covered by lava, sands, and other wastelands. The Gulf Stream moderates the climate. The capital is Reykjavík.

Demography. In 1993, the population was 264,922. In 1703, when the first census was done, the population was 50,358. In 1992, there were 63,540 families that averaged three members. In 1993, the population of the capital area was 154,268.

Linguistic Affiliation. Icelandic is a Germanic language related to Norwegian. Medieval Icelandic, the language of the historical-literary tradition, sometimes is called Old Norse. Icelandic has been said to be virtually unaltered since medieval times, although many Icelanders disagree. There are no family names. Everyone has one or two names and is referred to as the son or daughter of his or her father. Thus, everyone has a patronymic, or father's name. Directories are organized alphabetically by first name. There is some debate about the uniformity of the language. Purists of the nationalist-oriented independence tradition insist that there is no variation in Icelandic, but linguistic studies suggest variation by class. While all the people speak Icelandic, most also speak Danish and English.

Symbolism. The international airport is named Leif Erikson Airport after the first voyager to North America, and a statue of Erikson stands in front of the National Cathedral. A heroic statue of the first

Iceland

settler is in the downtown area of the capital. The nationalist-oriented ideology stresses identification with medieval culture and times while downplaying slavery and later exploitative relations of the aristocracy and commoners. This romantic view of the saga tradition informs nationalist symbolism and nationalist-influenced folklore. There is a whole genre of romantic landscape poetry depicting the beauty of the island. Some of it goes back to the saga tradition, quoting Gunnar, a hero of Njal's saga, who refused to depart after being outlawed because as he looked over his shoulder when his horse stumbled, the fields were so beautiful that he could not bear to leave. More recently, rhetoric about whaling has achieved symbolic proportions as some have viewed attempts to curtail the national tradition of whale hunting as an infringement on their independence. Independence Day on 17 June is celebrated in Reykjavík. Neighborhood bands march into the downtown area playing songs, and many people drink alcoholic beverages. The major symbols of Icelandicness are the language and geography, centered on the beauty of the landscape. Many people know the names of the farms of their ancestors and can name fjords and hills, and the map in the civic center in Reykjavík has no place names because it is assumed that people know them. The folkloristic tradition contains many stories of trolls, among them the ones that come from the wastelands to eat children at Christmas and their twelve sons who play pranks on people. Various features of landscape are associated with stories recorded in the official folklore.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. Between 1602 and 1787, Denmark imposed a trade monopoly that

Swimmers bathe in the Blue Lagoon thermal baths in Iceland.

restricted imports and kept fishing under its control. A farming elite developed a system of self-contained farms and opposed the development of fishing, which would threaten the supply of cheap labor if relied on. After independence, fishing finally developed. The trade monopoly organized Iceland as a tributary state for mercantile purposes and created a class of farmers with entrenched interests and power to defend them against the fisheries. The trade monopoly created the autonomous Icelandic farm as the primary social, economic, and political unit. When the tributary system became a hindrance to organizing for capitalism, the elite engineered backwardness to serve its interests. This backwardness was not a local dynamic and was not culturally determined but served a large international Danish system. When Denmark's absolute monarchy was replaced by a nation-state, this provided a context for Icelandic independence. Although farmers tried to perpetuate their hold over the economy, industrial fishing became the backbone of the national economy. The "independence struggle" started in the mid-nineteenth century. Nationalist ideology presents the movement as an autonomous great awakening. In the service of the independence movement, the elite developed distinctive images of what it meant to be Icelandic, aided by historians and legalists, folklorists, and linguists. These images described an ideal lifestyle of an elite. Danes thought Icelandic culture embodied the most noble elements in the Norse experience and looked to Iceland for inspiration. Thus, Icelandic leaders could argue that the nation's future should match the glories of its past. Icelandic students in Denmark began to import ideas of nationalism and romanticism. The Icelandic elite followed the Danes in identifying with a romantic image of a glorious Icelandic past. As the Danes began to modernize and develop, they set the conditions for Icelandic independence. Finally it was conditions beyond Danish control—when Denmark was occupied by Germany in World War II, followed by the occupation of Iceland by British and then American troops— that pushed Iceland into independence. Given independence and population growth, along with new sources of outside capital, the government focused on the development of industrial fishing and the infrastructure to support it.

National Identity. The working class identified with national political movements and parties and thus helped ratify the elite's vision of Iceland. The ideology developed by members of the farming elite was one of the individual, the holiness and purity of the countryside, and the moral primacy of the farm and farmers. The most significant individuals were the farmers. This ideology was perpetuated in academic writings, schools, and law. Foreign scholars and anthropologists, along with local folklorists, created a bureaucratic folklorism that considered the intellectual superior to the rural people and the rural people as the most superior of all exotics. Such constructs could not be perpetuated as most people abandoned the countryside in favor of fishing villages and wage work or salaried positions in Reykjavík. Icelanders generalized and democratized the concept of the elite and combined it with competitive consumerism. This led to a new cultural context that weakened the ideology of the farmer elite. The main ideological task of the independence movement was to develop a paradigm that would prove that the nationalistic power struggle would change the lives of ordinary people. The past and the countryside were emphasized as pure, while working people in the cities were considered trash. The folklore movement displaced discussions of competition for power to earlier times and reduced diversity to uniformity in service of the state. As the population grew and the economy turned more toward fishing in the coastal towns and villages, farmers lost their economic place. The main goal of the nationalist ideology that the elite promulgated was to conserve the old order. The glory of the sagas was held up as a model, and certain celebrations were revived to emphasize the connection. However, today most Icelanders live in the area of the capital, and their culture is international.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

In 1991, there were 4,754 farms. More than half the people (154,268) live in the Reykjavík area. The next largest town is Akurery, with a population of 14,799. Keflavík, where the NATO base and the international airport are, has a population of 7,581. The Westman Islands are home to 4,883 people. The realities of daily life for most people are urban and industrial or bureaucratic. Until recently, social life was centered on households and there was little public life in restaurants, cafés, or bars. There is a thriving consumer economy. People are guaranteed the right to work, health care, housing, retirement, and education. Thus, there is no particular need to save. People therefore purchase homes, country houses, cars, and consumer goods to stock them. Private consumption in 1993 reached $10,600 per capita.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. The writer Halldor Laxness once observed that "life is salt fish." During some of the events inspired by the romantic folkloric revival, people consume brennivín, an alcoholic beverage called "black death," along with fermented shark meat and smoked lamb, which is served at festive occasions. Icelanders are famous for the amount of coffee they drink and the amount of sugar they consume.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. For homecomings and family gatherings, there is usually a sumptuous spread of cakes and pastries, including crullers and thin pancakes rolled around whipped cream.

Basic Economy. The major occupations in 1991 were agriculture, fishing, and fish processing. The main industries were building, commerce, transportation and communications, finance and insurance, and the public sector. Fish and fish products are the major export item. While dairy products and meat are locally produced, grain products are imported. Some vegetables are produced in greenhouses, and some potatoes are locally produced. Other food is imported, along with many consumer goods. In 1993, consumer goods accounted for 37.2 percent of imports, intermediate goods 28 percent, fuels 8 percent, and investment goods 25.8 percent.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. There is a lack of extreme stratification in a country that values egalitarian relationships. Working-class people are likely to indicate their class status by language use, incorporating into their speech what purists call "language diseases."

Political Life

Government. Iceland has a multiparty parliamentary system, and there is a written constitution. Presidents are elected for four-year terms by direct popular vote but serve a parliamentary function and do not head a separate executive branch. The parliament is called Althingi after the medieval general assembly. It has sixty three members elected by popular vote for four-year terms. Each party puts forward a list of candidates, and people vote for parties, not candidates. The seats in the parliament are then distributed to parties according to the placement of people in their lists. Thus, elections

Flowers adorn a public square. Icelanders take extreme care in the upkeep of public areas.

have more to do with policies and positions on issues than with personalities.

Leadership and Political Officials. After elections, the president asks one party, usually the one with the largest number of votes, to form a government of cabinet officers. There has never been a majority in the parliament, and so the governments are coalitions. The real political competition starts after elections, when those elected to the parliament jockey for positions in the new government. If the first party cannot form a coalition, the president will ask another one until a coalition government is formed. Cabinet ministers can sit in the parliament but may not vote unless they have been elected as members. This cabinet stays in power until another government is formed or until there are new elections. The president and the Althingi share legislative power because the president must approve all the legislation the parliament passes. In practice, this is largely a ritual act, and even a delay in signing legislation is cause for public comment. Constitutionally, the president holds executive power, but the cabinet ministers, who are responsible to the Althingi , exercise the power of their various offices. The parliament controls national finances, taxation, and financial allocations and appoints members to committees and executive bodies. There is an autonomous judicial branch. The voting age is 18, and about 87.4 percent of the people vote. The major parties include the Independence Party, Progressive Party, People's Alliance, Social Democrats, Women's Party, and Citizens/ Liberal Party. Each party controls a newspaper to spread and propagate its views. The mode of interaction with political officials is informal.

Social Problems and Control. There are few social problems, and crime is minimal. There is some domestic abuse and alcoholism. The unemployment rate is very low. Police routinely stop drivers to check for drunkenness, and violators have to serve jail time, often after waiting for a space in the jail to become available. There are no military forces.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

Since independence, there has been a high standard of living. From 1901 to 1960, real national income rose tenfold, with an annual average growth rate over 4 percent. This was the period in which the national economy was transformed from a rural economy based on independent farms to a capitalist fishing economy with attendant urbanization.

Gender Roles and Statuses

The Relative Status of Women and Men. There is more gender equality than there is in many other countries. The open nature of the political system allows interested women to organize as a political party to pursue their interests in the parliament. There are women clergy. Fishing is largely in the hands of men, while women are more prominent in fish processing.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. There is a relative lack of formal marriage, and out-of-wedlock births (13 to 36 percent) have never been stigmatized. Women frequently have a child before they marry. Many people are related to numerous half siblings from their parents' other children by other mates.

Domestic Unit. The domestic unit is the household, and larger kin groups come together for annual reunions. Friendship and other connections are very important, and many people who are referred to by kin terms are not genealogically related.

Socialization

Infant Care. Infants are isolated in carriages and cribs, not continuously held. Public health nurses check on newborns to be sure they are on the growth curves and check for signs of neglect, abuse, or disease. Since both men and women usually work, it is common for children to be kept in day care centers from an early age.

Child Rearing and Education. Children are centers of attention, and classes are given on child rearing and parenting. Thus, even teenagers are familiar with approved methods of child rearing. Education is respected and considered a basic right. University education is available to all who want it and can afford minimal registration fees. Education is compulsory between ages 7 and 16 but may be continued in middle schools or high schools, many of which are boarding schools.

Higher Education. A theological seminary was founded in 1847, followed by a medical school in 1876 and a law school in 1908; these three schools were merged in 1911 to form the University of Iceland. A faculty of philosophy was added to deal with matters of ideology (philology, history, and literature). Later, faculties of engineering and social sciences were added.

Etiquette

Social interaction is egalitarian. Public comportment is quiet and reserved.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. The state church is the Evangelical Lutheran Church, of which 92.2 percent of the population are nominal if not practicing members. Other Lutherans constitute 3.1 percent of the population, Catholics 0.9 percent, and others 3.8 percent. There is a Catholic church and churches of other groups in Reykjavík. There are many Lutheran churches, and their clergy substitute for social service agencies. Other religions include Seventh-Day Adventists, Pentecostals, Jehovah's Witnesses, Bahai, and followers of the Asa Faith Society, which looks to the gods represented in the saga tradition. Less than 2 percent of the population in 1993 was not affiliated with a religious denomination. Confirmation

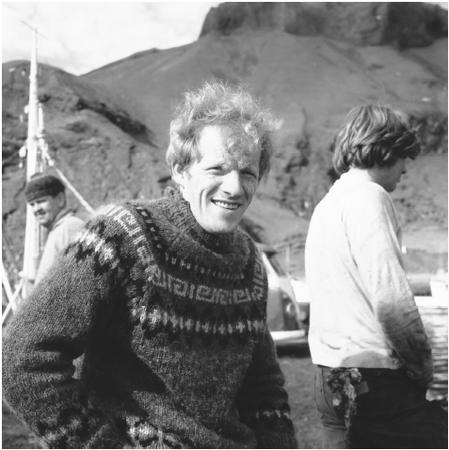

Icelandic fishermen provide the key ingredient for one of the country's main exports, fish and fish products.

is an important ritual for adolescents, but many who are confirmed are not active.

Medicine and Health Care

Universal medical care is provided as a right. There is a modern medical system.

Secular Celebrations

Most holidays are associated with the Christian religious calendar. Others include the first day of summer on a Thursday from 19 to 25 April, Labor Day on 1 May, National Day on 17 June, and Commerce Day on the first Monday of August. These holidays are observed by having a day off from work and possibly traveling to the family summer house for a brief vacation.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. There is an art museum in Reykjavík, and several artists have achieved the status of "state artists" with government-funded studios, which become public museums after their deaths. There is a theater community in Reykjavík. Literature has a long history.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

The University of Iceland is the center for scientific research. There is much work on geothermal energy sources. The National Science Foundation funds research, and Iceland belongs to international federations for the support of physical and social science research. There is a faculty of engineering and a faculty of social science at the university.

Bibliography

Durrenberger, E. Paul. The Dynamics of Medieval Iceland: Political Economy and Literature . University of Iowa Press, 1992.

——. Icelandic Essays: Explorations in the Anthropology of a Modern Nation , 1995.

—— and Gísli Pálsson. The Anthropology of Iceland ,1989.

Pálsson, Gísli. Coastal Economies, Cultural Accounts: Human Ecology and Icelandic Discourse , 1990.

——. The Textual Life of Savants: Ethnography, Iceland, and the Linguistic Turn , 1995.

—— and E. Paul Durrenberger. Images of Contemporary Iceland: Everyday Lives and Global Contexts , 1996.