Culture of Honduras

Culture Name

Honduran

Alternative Names

Hondureño catracho (the national nickname; can be amusing, insulting, or friendly, depending on the context. "Catracho" comes from the name of Florencio Xatruch, the general who led the Honduran expeditionary force against William Walker in Nicaragua in 1856.)

Orientation

Identification. The name of the country means "depths." It was so named by Christopher Columbus on his fourth voyage because of the deep waters at the mouth of the Tinto o Negro River off the Mosquito Coast. Regional traditions exist in the south (Choluteca and Valle) and the north coast as well as among the minority ethnic groups. All these people self-identify as Hondurans, however. Spanish-speaking people in the center of the country are the most numerous and are culturally dominant. They do not use a special name to refer to themselves or their region.

Location and Geography. The nation has an area of 43,266 miles (112,492 square kilometers). Honduras is in the middle of Central America. The physical environment is tropical, with a long dry season (six months or more) in the south and the interior and a shorter dry season in the north. The center of the country originally was covered with pine and broadleaf forests of oak and other trees, but much of the pine forest has been logged and much of the oak forest has been cut for farming. The north coast was once primarily rain forest, but much of it has been cleared for commercial banana plantations. The northeast is called the Mosquitia. It includes the "Mosquito Coast," which is actually a long series of white sand beaches and freshwater lagoons. Inland from the coast, the Mosquitia has one of the last great stands of tropical rain forest left in North America, plus pine woods and grasslands.

Different ethnic groups live in specific environments. The Anglo-African-Caribbean "Bay Islanders" live on the Bay Islands off the north coast. The Garífuna people live along the Caribbean Coast of Central America, from Belize to Nicaragua. The Miskito and Tawahka people live in the rain forests of the eastern lowlands, and in similar lands in neighboring areas of Nicaragua. The Pech and Jicaque people live in some of the more remote areas in the central highlands. The Chortí and Lenca peoples live in the rugged western highlands. Hispanic-Hondurans live in the north, south, and center of the country.

The capital city, Tegucigalpa, was chosen because it is near the geographic center of the country. It completely fills a small, deep valley in the headwaters of the Choluteca River, in the central highlands.

Demography. Honduras had a population of 5,990,000 in 1998. In 1791, the population was only 93,501. The pre-Hispanic population was probably much higher, but conquest, slavery, and disease killed many people. The population did not reach one million until 1940.

The major ethnic group include the Chortí, a native people with a population of about five thousand in the department of Copán. There may still be a few people who can speak the Chortí language, which belongs to the Mayan family. The Lenca are a native people in the departments of La Paz, Intibucá, and Lempira, as well as some other areas. The Lenca language is extinct, and culturally the Lenca are similar in many ways to the other Spanish-speaking people in the country. The Lenca population is about one hundred thousand. The Jicaque are a native people who live in the department of Yoro and the community of Montaña de la Flor (municipality of Orica) in the department of

Honduras

Francisco Morazán. Only those in Montaña de la Flor still speak the Tol (Jicaque) language, which is in the Hokan family. The Jicaque group in Yoro is much larger and has been almost completely assimilated into the national culture. There are about nineteen thousand Jicaque in Yoro and about two hundred in Montaña de la Flor. The Pech are a native people in the departments of Olancho and Colón, with a few living in Gracias a Dios in the Mosquitia. They speak a Macro-Chibchan language and have a population of under three thousand. The Tawahka are a native people in the department of Gracias a Dios in the Mosquitia. Tawahka is a Macro-Chibchan language that is very closely related to Sumo, which is spoken in Nicaragua. Most Tawahkas also speak Misquito and Spanish. The Tawahka population is about seven hundred. The Misquitos are a native people with some African and British ancestry who reside in the department of Gracias a Dios in the Mosquitia. Misquito is a Macro-Chibchan language, although most Misquitos speak fluent Spanish. The Misquito population is about thirty-four thousand. The Garífuna are a people of African descent with some native American ancestry. They originated on the Caribbean island of Saint Vincent during colonial times from escaped slaves who settled among a group of Arawak-speaking Carib Indians and adopted their native American language. In 1797, the Garífuna were forcibly exiled by the British to Roatán in the Bay Islands. The Spanish colonial authorities welcomed the Garífuna, and most of them moved to the mainland. The Garífuna population is about one hundred thousand. The Bay Islanders are an English-speaking people who are long settled in the Caribbean. Some are of African descent, and some of British descent. The Bay Islanders population is about twenty-two thousand.

Linguistic Affiliation. Spanish is the dominant national language. Although originally imposed by the conquistadores, it has been widely spoken in Honduras for over two hundred years. Almost all residents speak Spanish, although some also speak English or one of the Native American languages discussed in the previous paragraph. Honduran Spanish has a distinct accent. Hondurans use some words that are not heard in other Spanish-speaking countries, and this gives their speech a distinctive character.

Symbolism. In spite of the 1969 war with El Salvador and tense relations with Nicaragua, the Honduran people feel that they are part of a larger Central American community. There is still a sense of loss over the breakup of Central America as a nation. The flag has five stars, one for each Central American country (Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica). Factory goods are not labeled "made in Honduras," but "Central American product, made in Honduras." Independence Day (15 September) is shared with the other Central American countries, and is a fairly muted national holiday. Some people complain that there is little point celebrating independence from Spain, since Honduras has become virtually a colony of the United States. By 1992, Columbus Day had become a day of bereavement, as Hondurans began to realize the depth of cultural loss that came with the Spanish conquest. May Day is celebrated with parades and speeches. In the 1990s, the national government found this symbol of labor unity threatening and called out the army to stand with rifles before the marching workers.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. Francisco Morazán led the fight for independence from Spain (achieved in 1821) and resistance to the breakup of Central America (1830). In 1855, North American soldiers of fortune (filibusterers) led by William Walker tried to convert Central America into a United States colony. They held Nicaragua until they were expelled in 1857 by Nicaraguan regular troops and volunteer fighters. In 1860 Walker invaded Honduras, at Trujillo, where he ended up before an army firing squad. United States banana companies dominated Honduran politics after 1911. Fruit companies were able to choose presidents and as late as the 1970s were powerful enough to refuse to pay higher taxes imposed on banana exports by the military government. A 1920 letter by a U.S. fruit company executive describing how easily Honduran politicians could be bribed and dominated is still a source of national embarrassment.

National Identity. Because of the relationship of Honduras with the United States, the national culture often is defined in opposition to that of the United States. Hondurans feel an affinity with other Latin Americans and Central Americans, although this is mixed with fear and resentment of some neighboring countries, especially El Salvador and Nicaragua.

The Spanish conquest was a violent episode of genocide and slavery. It produced a people with blended European, native American, and African ancestry. Many Latin American countries have a similar large ethnic group called mestizos or criollos, but what is unusual about Honduras is that the Spanish-speaking people of mixed ancestry, who make up about 88 percent of the population, proudly call themselves indios (Indians). Hondurans call indigenous peoples indígenas, not indios.

Ethnic Relations. Music, novels, and television shows circulate widely among Spanish-speaking countries and contribute to a sense of Latin culture that transcends national boundaries. Ethnic relations are sometimes strained. For centuries, most indigenous peoples lost their land, and the nation did not value their languages and cultures. The Indian and Garífuna people have organized to insist on their civil and territorial rights.

The Bay Islanders (including those of British decent and those of African descent) have ties with the United States. Because the Islanders speak English, they are able to work as sailors on international merchant ships, and despite their isolation from the national culture, they earn a higher income than other residents.

Arab-Hondurans are descended from Christian Arabs who fled Muslim persecution in the early twentieth century after the breakup of the Ottoman Empire. Many have successful businesses. Some Hispanic-Hondurans envy the economic status of Arab-Hondurans, who are usually called turcos, a name they dislike since they are not of Turkish descent. (Many of the original Arab immigrants carried passports of the Ottoman Empire, whose core was Turkey.)

Urbanism,Architecture, and the Use of Space

In the cities, houses are made of store-bought materials (bricks, cement, etc.), and some of the homes of wealthy people are large and impressive. In the countryside, each ethnic group has a distinct architectural style. Most of the homes of poor rural people are made of local materials, with floors of packed earth, walls of adobe or wattle and daub, and roofs of clay tiles or thatch.

The kitchen is usually a special room outside the house, with a wood fire built on the floor or on a

Rural homes vary in style but are usually made of local materials.

raised platform. Porches are very common, often with one or more hammocks. The porch often runs around the house and sometimes connects the house to the kitchen. When visiting a rural home, one is received on the breezy porch rather than inside the house. The porch is used like the front parlor. The house is often plastered with mud, and people paint designs on it with natural earths of different colors.

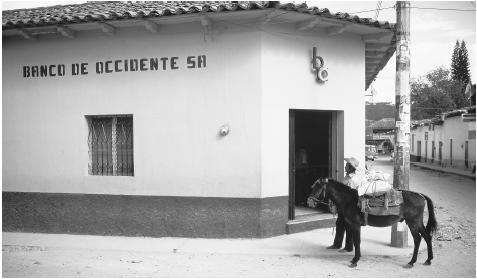

A central plaza forms the heart of most towns. Important government buildings face it, as does a Catholic chapel or cathedral. Successful businesses are situated on or near the plaza. People are attracted to their city centers, and some municipal governments have started converting inner-city streets to pedestrian walkways to accommodate the crowds. Plazas are formal parks. People sit on benches under the trees and sometimes chat with friends or strangers. Villages have an informal central place located near a soccer field and a few stores and a school. In the afternoon, some people tie their horses to the front porch of the store, have a soft drink, and watch children play ball.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Beans and corn tortillas are the mainstays of the diet. The beans are usually fried, and the tortillas are small, thick, and usually handmade; ideally, they are eaten warm. A farm worker's lunch may be little more than a large stack of tortillas, a few spoonfuls of beans, and some salt. The ideal meal includes fried plantains, white cheese, rice, fried meat, a kind of thickened semisweet cream called mantequilla , a scrambled egg, a cabbage and tomato salad or a slice of avocado, and a cup of sweet coffee or a bottled soft drink. These meals are served in restaurants and homes for breakfast, lunch, and dinner year-round. Plantains and manioc are important foods in much of the country, especially the north and the Mosquitia. Diners often have a porch or a door open to the street. Dogs, cats, and chickens wander between the tables, and some people toss them bones and other scraps. There are Chinese restaurants owned by recent immigrants. In the early 1990s, North American fast-food restaurants became popular.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Special and holiday foods are an improved version of the typical meal but feature more meat and perhaps more of an emphasis on cream and fried plantains. Christmas food includes torrejas , a white bread soaked in hot syrup, and nacatamales, which are like the Mexican tamales, but are larger and moister with a more gelatinous dough and are wrapped in banana leaves.

Basic Economy. Fifty-four percent of economically active people work in agriculture. Most are smallholder farmers who call themselves campesinos . Because the internal food market is irregular, campesinos try to grow their own maize (corn), beans, and plantains. Once they have achieved that goal, they raise a cash crop. Depending on whether they live in a valley, the mountains, or along the coast and on whether they live near a good road, a campesino household may raise a cash crop of coffee, cattle, cabbage, tomatoes, citrus fruit, maize, beans, or other vegetables. Long-term donations of wheat from the United States have kept food prices low but have provided a disincentive for grain farmers. Some large-scale commercial farmers produce melons, beef, coffee, and shrimp for export.

Land Tenure and Property. Land may be private, communal, cooperative, or national. Private land includes buildings and most of the agricultural and grazing land and some forested land. Communal land usually consists of the forest or rough pasture traditionally used by a rural community. Forest trees are owned by the government even if an individual owns the land. Many smallholders and rural communities do not have clear title to or ownership papers for their land even though their families have worked it for generations.

Cooperatives were formed in the mid-1970s to manage land taken from large landowners under agrarian reform policies. Much of this land is of good quality, and cooperatives can be several hundred acres in size. Most of the members or their parents once worked on large estates that were expropriated, usually by the workers and occasionally with some violence, and often suffered some repression while doing so. These farms are still owned cooperatively, although in almost all cases the farmers found it too difficult to work them collectively, and each household has been assigned land to work on its own within the cooperative's holdings. By 1990, 62,899 beneficiaries of agrarian reform (about 5 percent of the nation, or 10 percent of the rural people) held 906,480 acres of land (364,048 hectares, or over 4 percent of the nation's farmland). In the 1970s and 1980s, wealthy people, especially in the south, were able to hire lawyers to file the paperwork for this land and take it from the traditional owners. The new owners produced export agricultural products, and the former owners were forced to become rural laborers and urban migrants or to colonize the tropical forests in eastern Honduras.

As late as the 1980s there was still national land owned but not managed by the state. Anyone who cleared and fenced the land could lay claim to it. Some colonists carved out farms of fifty acres or more, especially in the eastern forests. By the late 1980s, environmentalists and indigenous people's advocates became alarmed that colonization from the south and the interior would eliminate much of the rain forest and threaten the Tawahka and Miskito peoples. Much of the remaining national land has been designated as national parks, wilderness areas, and reserves for the native peoples.

Commercial Activities. In the 1990s, Koreans, Americans, and other foreign investors opened huge clothing factories in special industrial parks near the large cities. These maquilas employ thousands of people, especially young women. The clothing they produce is exported.

Major Industries. Honduras now produces many factory foods (oils, margarine, soft-drinks, beer), soap, paper, and other items of everyday use.

Trade. Exports include coffee, beef, bananas, melons, shrimp, pineapple, palm oil, timber, and clothing. Half the trade is with the United States, and the rest is with other Central American countries, Europe, Japan, and the rest of Latin America. Cotton is now hardly grown, having been replaced by melon and shrimp farms in southern Honduras. Petroleum, machinery, tools, and more complicated manufactured goods are imported.

Division of Labor. Men do much of the work on small farms. Tortilla making is done by women and takes hours every day, especially if the maize has to be boiled, ground (usually in a metal, hand-cranked grinder), slapped out, and toasted by hand, and if the family is large and eats little else. Campesino children begin playing in the fields with their parents, and between the ages of about six and twelve, this play evolves into work. Children specialize in scaring birds from cornfields with slingshots, fetching water, and carrying a hot lunch from home to their fathers and brothers in the field. Some villagers have specialties in addition to farming, including shopkeeping, buying agricultural products, and shoeing horses. In the cities, job specialization is much like that of other countries, with the exception that many people learn industrial trades (mechanics, baking, shoe repair, etc.) on the job.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. Large landholdings and, to a lesser extent, successful businesses generate income for most of the very wealthy. Some of these people,

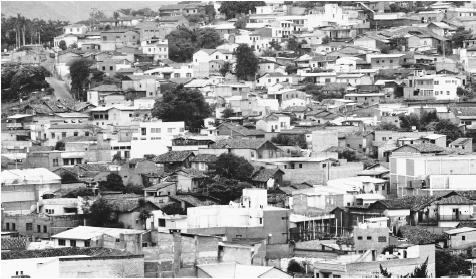

In cities such as Tegucigalpa, extended families may share the same house until the younger couple can afford their own home.

especially in the city of Danlí, consider themselves a kind of aristocracy, with their own social clubs and old adobe mansions downtown. These people import new cars and take foreign vacations.

Educated, professional people and the owners of mid size businesses make up a group with a lifestyle similar to that of the United States middle class. However, some professionals earn only a few hundred dollars a month. They may work several jobs and tend to have old cars and small houses that are often decorated with much care.

Urban workers are often migrants from the countryside or the children of migrants. They tend to live in homes they have built for themselves, gradually improving them over the years. Their earnings may be around $100 a month. They tend to travel by bus.

Campesinos may earn only a few hundred dollars a year, but their lifestyle may be more comfortable than their earnings suggest. They often own land, have horses to ride, and may have a comfortable, if rudimentary home of wood or adobe, often with a large, shady porch. If a household has a few acres of land and if the adults are healthy, these people usually have enough to feed their families.

Symbols of Social Stratification. As in many countries, wealthier men sometimes wear large gold chains around their necks. Urban professionals and workers dress somewhat like their counterparts in northern countries. Rural people buy used clothing and repair each garment many times. These men often wear rubber boots, and the women wear beach sandals. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, many men carried pistols, usually poked barrel-first into the tops of their trousers. By 2000 this custom had become somewhat less common. Many campesinos, commercial farmers, and agricultural merchants carried guns at that time.

There is a subtle difference in accent among the different classes. The highest-status people pronounce words more or less as in standard Spanish, and working-class pronunciation uses a few systematic and noticeable modifications.

Political Life

Government. The most important political offices are the national president, members of congress ( diputados ) and city mayors. In addition to the executive branch (a president and a cabinet of ministers) and a unicameral congress, there is a supreme court.

Leadership and Political Officials. Honduras still has the two political parties that emerged in the nineteenth century: the Liberales and the Nacionalistas. The Liberales originally were linked to the business sector, and the Nacionalistas with the wealthy rural landowners, but this difference is fading. Both parties are pro–United States, and pro-business. There is little ideological difference between them. Each is associated with a color (red for Liberals and blue for Nationalists), and the Nationalists have a nickname ( los cachurecos which comes from the word cacho, or "horn," and refers to the cow horn trumpet originally used to call people to meetings). People tend to belong to the same party as their parents. Working on political campaigns is an important way of advancing in a party. The party that wins the national elections fires civil servants from the outgoing party and replaces them with its own members. This tends to lower the effectiveness of the government bureaucracy because people are rewarded not for fulfilling their formal job descriptions but for being loyal party members and for campaigning actively (driving around displaying the party flag, painting signs, and distributing leaflets).

Political officials are treated with respect and greeted with a firm handshake, and people try not to take up too much of their time. Members of congress have criminal immunity and can literally get away with murder.

Social Problems and Control. Until the 1990s, civilians were policed by a branch of the army, but this force has been replaced by a civil police force. Most crime tends to be economically motivated. In cities, people do not leave their homes unattended for fear of having the house broken into and robbed of everything, including light bulbs and toilet paper. Many families always leave at least one person home. Revenge killings and blood feuds are common in some parts of the country, especially in the department of Olancho. Police are conspicuous in the cities. Small towns have small police stations. Police officers do not walk a beat in the small towns but wait for people to come to the station and report problems. In villages there is a local person called the regidor , appointed by the government, who reports murders and major crimes to the police or mayor of a nearby town. Hondurans discuss their court system with great disdain. People who cannot afford lawyers may be held in the penitentiary for over ten years without a trial. People who can afford good lawyers spend little time in jail regardless of the crimes they have committed.

Until after the 1980s, crimes committed by members of the armed forces were dismissed out of hand. Even corporals could murder citizens and

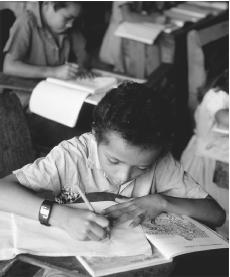

Rural children help with farm chores in addition to their school work.

never be charged in court. In 1991, some military men, including colonels, raped and murdered a university student. Her school and family, the press, and the United States embassy exerted pressure until two men were sent to prison. This event was the start of a movement to modernize and improve the court system.

Military Activity. The Cold War was difficult for Honduras. In the past thirty years, the military has gone through three phases. The military government of the 1970s was populist and promoted land reform and tried to control the banana companies. The governments in the 1980s were nominally civilian, but were dominated by the military. The civilian governments in the 1990s gradually began to win control of the country from the military.

In the 1980s, the United States saw Honduras as a strategic ally in Central America and military aid exceeded two hundred million dollars a year. The army expanded rapidly, and army roadblocks became a part of daily life. Soldiers searched cars and buses on the highways. Some military bases were covers for Nicaraguan contras. In the mid-1990s, the military was concerned about budget cuts. By 2000, the military presence was much more subtle and less threatening.

For several reasons, the Honduran military was less brutal than that of neighboring countries. Soldiers and officers tended to come from the common people and had some sympathies with them. Officers were willing to take United States military aid, but were less keen to slaughter their own people or start a war with Nicaragua.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

The most important social change in the last few years has been the influence of Evangelical Protestant missionaries, who have converted many Hondurans to Pentecostal religions. There are also urban social change agencies, and many that work in the villages. Their fields of activity include soil conservation, gardening, and natural pest control. One of the most important reformers was an agronomist educator-entrepreneur named Elías Sánchez, who had a training farm near Tegucigalpa. Sánchez trained tens of thousands of farmers and extension agents in soil conservation and organic fertilization. Until his death in 2000, he and the people he inspired transformed Honduran agriculture. Farmers stopped using slash-and-burn agriculture in favor of intensive, more ecologically sound techniques.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

United States military aid was accompanied by economic aid. Much of this money was disbursed to nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and during the 1980s there were over two hundred of these groups. About a hundred worked in agricultural programs. CARE, Catholic Relief Services, World Neighbors, and Habitat for Humanity were some of the many international organizations that opened offices in Honduras. By the early 1990s, Honduran biologists and some foreign scientists and activists were able to attract attention to the vast forests, which were often the homes of native peoples and were under threat from logging, colonial invasion and cattle ranching. The Miskito people's NGO, Mopawi, was one of several native people's organizations that attracted funding, forged ties with foreign activists, and were able to reverse destructive development projects. Most native peoples now have at least one NGO that promotes their civil rights. In the large cities there are some organizations that work in specific areas such as street children and family planning. Rural people receive much more attention from NGOs than do the urban poor.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. Men are more prominent than women in public life, but women have served as judges, big city mayors, trial lawyers, members of congress, cabinet members, and heads of the national police force. Women have been especially active in religious life. To counter the inroads made by Evangelical missionaries, the Catholic Church encourages lay members to receive ecclesiastical training and visit isolated communities, to perform religious services. These people are called celebradores de la palabra ("celebrators of the word"). They hold mass without communion. Many of them are women. Women also manage stores and NGOs and teach at universities. Male-only roles include buying and trucking agricultural products, construction, bus and taxi drivers, and most of the military.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Honduran people occasionally say that theirs is a machista (macho, sexist) country. This is mostly a stereotype, but some men shout catcalls at women on the street, especially when the men are in groups. There are also cases of sexual harassment of office staff. However, most men are fond of their families, tolerant of their behavior, and sensitive to women, who often have jobs outside the home or run small stores. Adolescents and young adults are not subject to elaborate supervision during courtship.

Marriage,Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Marriage is based on the Western ideal of falling in love. There are few formal rules prohibiting marriage with people of different social backgrounds, although people tend to marry neighbors or people they meet at school or work. Almost everyone eventually marries or lives with someone and has children. Founding a household is a financial struggle for most couples, and so women's earnings are appreciated. Divorce and remarriage are fairly common and are slightly stigmatized. Monogamy is the formal rule, although a middle-aged man who can afford to may set up a separate house with a younger woman. If they find out about the younger women, most wives find the idea disgusting and threatening to the marriage.

Domestic Unit. The ideal household of a couple and their children is not always possible. When young couples cannot afford housing, they may live with their parents until they have several children of their own. As in other Latin American countries,

Horses and mules provide transportation for some small landholders.

when a couple marries, their new family assumes both of their names. For example, if a woman named María García marries a man named Carlos Martínez, they and their children become the Martínez-García family. In many households, men and women make major decisions together regarding household expenses, children's education, etc. In the cities, many households with only a moderate income include a live-in domestic servant who does the housekeeping.

Inheritance. Inheritance practice varies widely, but in general when a person dies the widow or widower inherits half the property (called the parte conyugal, or "the spouse's part") and the children get the other half, unless a will was made to the contrary. The spouse's part provides economic security for widows and helps preserve farms more or less intact. Sometimes there is a preference for the oldest son to inherit a larger share. There is also a tendency for sons to inherit land and daughters to inherit livestock, furniture, and money.

Kin Groups. In the cities, families tend to spend Sunday afternoon having an elaborate meal with the wife's parents. The ideal is for married children to live near their parents, at least in the same city, if not in the same neighborhood or on a contiguous lot. This is not always possible, but people make an effort to keep in touch with the extended family.

Socialization

Child Rearing and Education. Urban professionals and elites are indulgent toward children, rarely punishing them and allowing them to interrupt conversations. In stores, middle-class shoppers buy things their children plead for. Obedience is not stressed. Bourgeois children grow up with self-esteem and are encouraged to feel happy about their accomplishments.

The urban poor and especially the campesinos encourage children to play in small groups, preferably near where adults are working. Parents are not over protective. Children play in the fields where their parents work, imitating their work, and after age of six or seven they start helping with the farm work. Campesinos expect children to be obedient and parents slap or hit disobedient children. Adults expect three- to four-year-old children to keep up with the family while walking to or from work or shopping, and a child who is told to hurry up and does not may be spanked. Campesino children grow up to be disciplined, long-suffering, and hard working.

Higher Education. Higher education, especially a degree from the United States or Europe, is valued, but such an education is beyond the reach of most people. There are branches of the National University in the major cities, and thousands of people attend school at night, after work. There are also private universities and a national agricultural school and a private one (Zamorano).

Etiquette

A firm handshake is the basic greeting, and people shake hands again when they part. If they chat a bit longer after the last handshake, they shake hands again just as they leave. Among educated people, when two women greet or when a man greets a woman, they clasp their right hands and press their cheeks together or give a light kiss on the cheek. Campesinos shake hands. Their handshakes tend to be soft. Country women greeting a person they are fond of may touch the right hand to the other person's left elbow, left shoulder, or right shoulder (almost giving a hug), depending on how happy they are to see a person. Men sometimes hug each other (firm, quick, and with back slapping), especially if they have not seen each other for a while and are fond of each other. This is more common in the cities. Campesinos are a little more inhibited with body language, but city people like to stand close to the people they talk to and touch them occasionally while making a point in a conversation. People may look strangers in the eye and smile at them. People are expected to greet other office workers as they pass in the hall even if they have already greeted them earlier that day. On country roads people say good-bye to people they pass even if they do not know each other. In crowded airports and other places where people have to wait in a long, slow line, some people push, shove, cut in front of others, go around the line, and attract attention to themselves to get served first.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Almost all Hondurans believe in God and Jesus Christ, though sometimes in a vague way. In a traditionally Catholic country, many people have joined Evangelical Protestant churches. People usually keep their religious beliefs to themselves but Catholics may wear a crucifix or religious medal around their necks. Many people have a sense of divine destiny. Accidental death is attributed to the will of God rather than to a seat belt that was not buckled or another physical cause. The upper classes are still predominantly Catholic, while many of the urban poor are now Evangelical. Newspapers carry stories of witchcraft, writing about people who were ill until a healer sucked a toad or a sliver of glass from their bodies.

Religious Practitioners. The Catholic Church is the national religion, as stated in the Constitution. However, the liberal reforms of the 1820s led to the confiscation of Church property, the closing of the seminary, and a great decline in the number and morale of the Catholic clergy. By the 1960s mass was only heard regularly in the larger towns. At that time, foreign clergy, including French Canadians, began revitalizing the Honduran Church. Many priests supported campesino movements in the 1970s, and some were killed for it by the military. In the 1980s the bishops were strong enough to play a key role in resisting pressure from the United States for Honduras to go to war with Nicaragua. Various Protestant churches have been active in Honduras since the early twentieth century, especially since the 1970s, and have gained many converts. The Evangelical clergy is an informal lay clergy for the most part and small Pentecostal chapels are common in villages and in poorer neighborhoods in the cities.

Rituals and Holy Places. Most Catholics go to church only on special occasions, such as Christmas and funerals. Evangelicals may go to a small chapel, often a wood shack or a room in a house, for prayer meetings and Bible readings every night. These can be important havens from the pressures of being impoverished in a big city.

There is a minor ritual called cruzando la milpa ("crossing the cornfield") practiced in the Department of El Paraíso in which a magico-religious specialist, especially one who is a twin, eliminates a potentially devastating corn pest such as an inch-worm or caterpillar. The specialist recites the Lord's Prayer while sprinkling holy water and walking from one corner to the other of the cornfield in a cross pattern. This person makes little crosses of corn leaves or caterpillars and buries them in four spots in the field.

Death and the Afterlife. Beliefs about the afterlife are similar to the general Western tradition. An additional element is the concept of the hejillo , (standard Spanish: hijillo ) a kind of mystic contagion that comes from a dead human body, whether death was caused by age, disease, or violence. People who must touch the body wash carefully as soon as possible to purify themselves.

Commercial agriculture is an important part of the Honduran economy.

Medicine and Health Care

Sickness or an accident is a nightmare for people in the countryside and the urban poor. It may take hours to get a patient to a hospital by traveling over long dirt roads that often lack public transportation. Doctors may be unable to do much for a patient if the patient's family cannot afford to buy medicine. If the patient is an adult, the household may have to struggle to make a living until he or she recovers. Some traditional medical practitioners use herbal medicines and set broken bones.

Secular Celebrations

Independence Day falls on 15 September and features marches and patriotic speeches. Labor Day, celebrated on 1 May, includes marches by workers. During Holy Week (the week before Easter), everyone who can goes to the beach or a river for picnics and parties. On the Day of the Cross ( Día de la Cruz ) in May in the countryside, people decorate small wooden crosses with flowers and colored paper and place the crosses in front of their homes in anticipation of the start of the rainy season. Christmas and the New Year are celebrated with gift giving, festive meals, dancing, and fireworks.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. Some art is publicly supported through the Ministry of Culture, as well as through sales of tickets, CDs, etc. Some artists also have day jobs.

Literature. There is a modest tradition of serious literary fiction. The novel Prisión Verde ( Green Prison ) by Ramón Amaya is perhaps the best known work of fiction. It describes the sufferings of workers on an early twentieth century banana plantation.

Graphic Arts. There is a Honduran school of impressionist painting whose favorite themes include village street scenes. This style was first developed by Antonio Velázquez of the historic mining village of San Antonio de Oriente, department of Francisco Morazán, in the 1950s. Velázquez was the barber at the nearby agricultural college at Zamorano. He was self-taught, and Hondurans refer to his style as "primitivist." Newspaper cartoons are popular and important for social critique. The cartoonist Dario Banegas has a talent for hilarious drawings that express serious commentary.

Performance Arts. There are various theater groups in San Pedro Sula and Tegucigalpa, of which the most important is the National Theater of Honduras (TNH), formed in Tegucigalpa in 1965. Its directors have been faculty members of various public schools and universities. Other groups include University Theater of Honduras (TUH) and the Honduran Community of Theater Actors (COMHTE), formed in 1982. These groups have produced various good plays. Honduras also has a National School of Fine Arts, a National Symphonic Orchestra, and various music schools. There are a handful of serious musicians, painters, and sculptors in Honduras, but the most well-known group of artists may be the rock band Banda Blanca, whose hit single "Sopa de Caracol" (Conch Soup) was based on Garífuna words and rhythms. It topped Latin music charts in the early 1990s. There are still some performances of folk music at fiestas and other events, especially in the country. The accordion, guitar, and other string instruments are popular.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

Perhaps the most highly developed social science is the archaeological study of the ancient Maya at the site of Copán and elsewhere in western Honduras. Much of this work is done by foreigners, but many Hondurans also conduct research. Among the applied sciences, the best known institution is the Pan-American School of Agriculture (Zamorano), near Tegucigalpa, where scientists and students conduct agricultural research. Zamorano attracts an international student body and faculty and offers the best practical education in commercial agriculture in Latin America. The Honduran Agricultural Research Foundation (FHIA) on the north coast, was once a research center for the banana industry. It is now supported by the Honduran and United States governments and other donors and conducts research on tropical crops.

Bibliography

Aguilar Paz, Jesús. Tradiciones y Leyendas de Honduras, 1972.

Becerra, Longino. Evolución Histórica de Honduras, 1999.

Beneditt, Leonardo, Ismael Zepeda, JoséAntonio Montoya et al. Enciclopedia Multimedia Honduras Nuestro País, 1999.

Bentley, Jeffery W. Diccionario Campesino Hondureño, in press, probable date of publication 2001.

Chapman, Anne. Masters of Animals: Oral Traditions of the Tolupan Indians, Honduras, 1978.

——. Los Hijos del Copal y la Candela, 1992.

Coelho, Ruy Galvão de Andrade. Los Negros Caribes de Honduras, 1995.

Durham, W. H. Scarcity and Survival in Central America: The Ecological Origins of the Soccer War, 1979.

Fash, William L. & Ricardo Agurcia Fasquelle. Visión del Pasado Maya, 1996.

Gamero, Manuel. "Iberoamérica y el Mundo Actual." In A. Serrano, O. Joya, M. Martínez, and M. Gamero (eds.), Honduras Ante el V Centenario del Descubrimiento de América, 1991.

Joya, Olga. "Identidad Cultural y Nacionalidad en Honduras." In A. Serrano, O. Joya, M. Martínez, and M. Gamero (eds.), Honduras Ante el V Centenario del Descubrimiento de América, 1991.

Martínez Perdomo, Adalid. La Fuerza de la Sangre Chortí, 1997.

Murray, Douglas L. Cultivating Crisis: The Human Cost of Pesticides in Latin America, 1994.

Pineda Portillo, Noé. Geografía de Honduras, 1997.

Pineda Portillo, Noé, Fredis Mateo Aguilar Herrera, Reina Luisa Portillo, José Rolando Díaz, and Julio Antonio Pineda. Diccionario Geográfico de América Central, 1999.

Salinas, Iris Milady. Arquitectura de los Grupos Étnicos de Honduras, 1991.

Salomón, Leticia. Poder Civil y Fuerzas Armadas en Honduras, 1997.

Stonich, Susan C. I Am Destroying the Land: The Political Ecology of Poverty and Environmental Destruction in Honduras, 1993.

Tucker, Catherine M. "Private Versus Common Property Forests: Forest Conditions and Tenure in a Honduran Community." Human Ecology, 27 (2): 201–230, 1999.