Culture of Guinea-Bissau

Culture Name

Guinean

Alternative Name

Formally known as The Republic of Guinea-Bissau

Orientation

Identification. "Guinea" was used by European explorers and traders to refer the coast of West Africa. It comes from an Arabic term meaning "the land of the blacks." "Bissau," the name of the capital, may be a corruption of "Bijago," the name of the ethnic group that inhabits the dozens of small islands along the coast. The combined name distinguishes the country from its southern neighbor, Guinea.

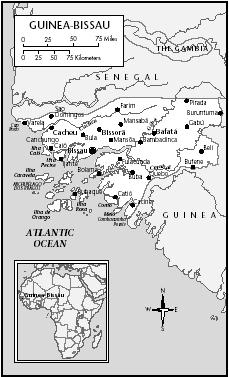

Location and Geography. Guinea-Bissau, one of the smallest and poorest West African nation-states, is surrounded by former French colonies. Sharing a border to the north with Senegal and to the south with Guinea, it has a land area of 13,944 square miles (36,125 square kilometers). The terrain is generally flat and nearly at sea level, although there are hills in the southeastern region. Wide tidal estuaries surrounded by mangrove swamps penetrate forty miles into the interior, where coastal rain forest gives way to sparsely wooded savanna.

Demography. In 1998, the population was at 1,206,311. The population is 76 percent rural, but almost 20 percent of the inhabitants live in the capital city. More than half the citizens were born after independence in 1974. Fula and Mandinga, who were traditionally politically centralized and make up the Moslem majority in the interior, account for roughly 30 percent of the population. Balanta, Manjaco, and Papel in the coastal and tidal zone constitute a sizable demographic majority.

Linguistic Affiliation. Government documents are written in Portuguese, students beyond the first few years of elementary school are taught in Portuguese, and government officials speak that language. However, only about 10 percent of the citizens are fluent in Portuguese. The national lingua franca is Criolu, which is derived primarily from Portuguese. Almost all Guineans born after 1974 know Criolu, although most speak it as a second language. Criolu developed in the era of slave trading, when it was used for communication between Portuguese merchant-administrators and the local populations. It became the primary language of Cape Verdeans, who were descendants of West African slaves and resettled in Portuguese coastal enclaves. These people were employed by the government in the lower levels of the colonial bureaucracy and engaged in local commercial activities. Criolu became the de facto national language during the struggle for liberation (1961–1974). Today Criolu is associated with an urban ethnic minority that identifies itself as Cape Verdean. It is also the language of national identity. Patriotic songs and slogans are invariably in Criolu and the national news is broadcast in that language.

Most residents are more comfortable speaking local African languages; close to half the population is monolingual in a local language. Balanta, Manjaco, and Papel speak related but mutually unintelligible languages that are distantly related to languages spoken in Senegal. The language of the Bijagos islanders off the coast is unrelated to that of any neighboring group. The languages spoken by Mandinga and Fula allow them to communicate with their cultural kin in neighboring nations.

Symbolism. The flag, with horizontal stripes of green, red, and yellow and a black star in the center, reflects an explicit concern to define the country in terms of national liberation and as pan-African rather than ethnic. During the revolution, efforts were made to minimize ethnic distinctions, and this

Guinea-Bissau

effort is reflected in the pervasive use of Criolu as the language of political slogans and patriotic celebration. Schools and avenues are named after heroes of the revolution, such as Domingos Ramos, who was killed while leading the first organized guerrilla battalion. Pan-African martyrs to national liberation such as Patrice Lumumba are similarly enshrined.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. By the sixteenth century, European traders had established permanent trading posts along the coast and encouraged local peoples to raid their neighbors for slaves. The slave trade created and reinforced ethnic distinctions in the region. Bijagos became notorious slave raiders, and Manjaco and Papel produced food for the coastal trading posts, along with trade goods, such as elaborately patterned textiles.

After the end of the slave trade in the mid-nineteenth century, Bijagos maintained their independence until the 1930s. Manjaco and Papel were among the first people in the region to migrate to Cape Verdean and European pontas or concessions, to share-crop peanuts. They were active in the wild rubber trade in the early twentieth century, migrating to Senegal and Gambia. The end of the slave trade led to political collapse and chaos among the more politically centralized Moslem groups in the interior. As Moslem factions fought, they also raided the coast, leading to confrontations with European traders.

The nation began as a colony consisting of the mainland territory and the islands of Cape Verde. Not until the first decades of the twentieth century were the Portuguese able to control the territory. Until then, the Portuguese had ruled only the coastal enclaves and were the virtual hostages of their African hosts, who controlled food and water supplies. In 1913 the Portuguese, under Teixeira Pinto, allied themselves with Fula troops under Abdulai Injai and defeated all the coastal groups. Then the Portuguese exploited divisions among the Moslems to destroy Injai and his followers, becoming the sole power in the region.

During the Salazarist era, the Portuguese built roads, bridges, hospitals, and schools. At the beginning of the 1960s their rule was contested by African nationalists under the leadership of Amilcar Cabral. By 1974, when Portugal recognized the nation's independence, the nationalist forces had developed a political and economic infrastructure providing basic services for the vast majority of local residents.

National Identity. The success of the revolutionary struggle created a strong sense of national identity that was reinforced by linguistic distinctiveness. Because of the upheaval caused by the war for liberation, large numbers of residents migrated to neighboring countries and to Europe.

Efforts to liberalize the economy and democratize the political system have led to corruption and exacerbated the gap in wealth between government officials and the citizens. As a result, the nation-state has come to be perceived as a platform for enriching oneself and one's family and a source of passports and identity papers that allow people to escape from the nation.

Ethnic Relations. In recent national elections, ethnically based parties have not been successful. As the nation becomes increasingly divided economically, ethnicity may become a way to mobilize factions.

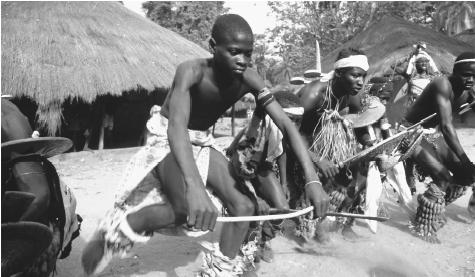

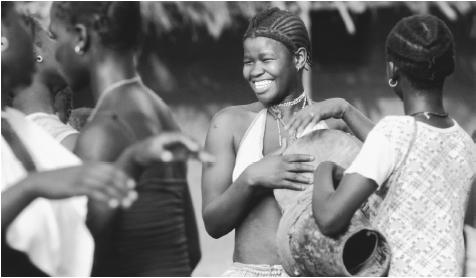

Young Bijagos Islands men perform ritual dances to attract wives in this matriarchal society. Most other ethnic groups in Guinea-Bissau are more patriarchal.

Recent coup attempts have divided the military, and animosity toward the wealthy may be increasingly directed at Cape Verdeans. Persons of Cape Verdean descent have been banned from running for the presidency.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

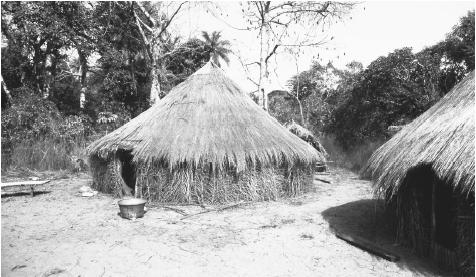

Bissau is a huge city relative to the country's size. Many of the larger buildings were constructed by the Portuguese. The core of the city is a planned colonial capital, with buildings, boulevards, and vistas in the modernist style. The smaller district capitals also feature colonial architecture. There are postcolonial buildings such as the Chinese hospital in Canchungo, but the architecture is largely West African. Rectangular houses with zinc roofs and concrete floors are common in villages and small towns. In villages, much housing is still traditional in form and materials. Dried mud and thatched circular huts in ethnically distinct styles are a common feature.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Rice is a staple among the coastal peoples. It is also a prestige food, and so the country imports it to feed the urban population. Millet is a staple crop in the interior. Both are supplemented with a variety of locally produced sauces that combine palm oil or peanuts, tomatoes, and onions with fish.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Most people participate in elaborate life cycle ceremonies in which family and community celebrates events such as birth, circumcision, marriage, and death. Most of these events, especially funerals, entail the sacrifice of livestock for consumption and ritual offering and the consumption of large quantities of palm wine or rum.

Basic Economy. The economy depends heavily on foreign aid to support the governmental bureaucracy, teachers and health workers, and the oversized military. The economy is basically agricultural; the vast majority of residents live off what they and their neighbors grow. Villagers depend on funds from emigrant workers. Urban government workers at all but the highest levels depend on their village kin for food. The West African franc (C.F.A.) is the currency used.

Land Tenure and Property. Traditional land tenure practices and systems of property ownership

Thatched houses in a Buboque Island village in the Bijagos Islands. Although cities display colonial architecture, villages feature these more traditional dwellings.

were not altered significantly by the colonial government or the independent state. A range of customary practices tend to protect the livelihoods of rural families and promote economic cooperation at the village level. There are no landless poor, but with economic liberalization and attempts to generate an export income, so-called empty lands have been granted to members of the government. Known as pontas, these concessions are enlarged extensions of earlier colonial practices. Ponta owners provide materials to local farmers who grow cash crops in exchange for a share of the profits or for wages.

Commercial Activities. There is a thriving rural market in livestock and foodstuffs. Most significantly Fula, Mandinga, and Balanta breed cattle and other livestock for consumption among the coastal groups who pay with funds repatriated by emigrant kin living in Senegal and Europe. There is some local business activity in Bissau but firms are small and relatively unimportant economically.

Trade. Guinea-Bissau produces and exports cashews, peanuts, fish and shellfish, and palm nuts. Export partners include Spain, Portugal, and Sweden. The country imports food, primarily rice, petroleum products, transport equipment, and consumer goods from Portugal, Russia, Senegal, and France.

Division of Labor. In urban centers, women work alongside men in the government. Urban men who are not employed by the government drive taxis, work in local factories, and are employed as laborers, sailors, and dock workers. Urban women do domestic work and trade in the markets. In the villages, children herd livestock, and young people work collectively to weed or prepare fields. Women do most domestic tasks. In some regions, women perform agricultural tasks that once were done by their husbands.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. In the colonial era, there were castes in Mandinga and Fula society, along with specific occupational groups. Among Manjaco and Papel, distinctions were made between aristocratic groups and commoners. Aristocrats among coastal and Moslem peoples continue to enjoy the privileges of rank.

Symbols of Social Stratification. Markers of wealth include business suits, cars, and cell phones. In the villages, funerals in wealthy families involve large slaughters of cattle; the dead are wrapped in greater quantities of cloth, and the guests are more numerous and better fed.

Political Life

Government. Until 1994, the country was a one-party republic with widespread participation and support. Today opposition parties have gained a considerable following and the current president ran against the revolutionary party.

The president selects a cabinet of ministers. Basic laws are enacted by the hundred delegates to the National Assembly, who are elected by universal sufferage.

Since the early 1990s, the government has increasingly privatized basic services and industries but continues to be the largest employer of workers outside the agricultural sector.

Leadership and Political Officials. Until the elections of 1999, almost all political leaders and officials came from the ranks of those who fought in the revolution. Midlevel and regional leaders often came from local aristocratic families.

Social Problems and Control. Social problems include smuggling, corruption, and emigration of the educated. With joblessness high in the capital city, there has been a rise in crime and prostitution.

Military Activity. The military forces that fought in the revolution emerged with prestige, organizational skill, and political authority. The armed forces were also large in proportion to the population. With the end of the Cold War and with economic and political liberalization, the army has become an economic burden and a threat to political stability. Several coups have been attempted since independence. The coup attempt of 1998 paralyzed the nation for six months and sent a flood of refugees to Senegal and Europe, because of protracted fighting in Bissau.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Rural Mandinga and Fula and the peoples of the coastal ethnic groups continue to practice arranged marriage in which a brideprice or groom service is given. However, young people can make matches on their own. Interethnic marriage rates are low but increasing. Men marry later than do women. Polygamy is accepted. Widows often remarry the husband's brother, thereby remaining in the same domestic household group.

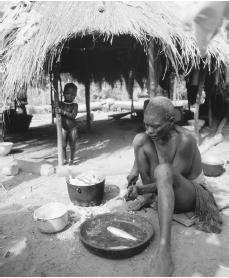

Women prepare fish of Buboque Island. Fish and shellfish are important in both Guinean diet and exports.

Domestic Unit. In the villages, the domestic unit is a large kinship group with common rights to agricultural property and obligations to work for one another.

Inheritance. Land passes from fathers to sons or from older brothers to younger brothers. Among the Manjaco and Papel, rice fields owned by domestic groups are inherited by a sister's sons, who act as caretaker-managers, dividing use rights to portions of the fields.

Kin Groups. All the ethnic groups are organized in fairly large kin groups known as clans or lineages. Most kin groups tend to be patrilineal and patrilocal, although there are also large categories of matrilineal kin who share rights to land and to local religious and political offices.

Socialization

Infant Care. High infant mortality rates result from a lack of modern health services.

Child Rearing and Education. Education at the primary school level is almost universal.

A peanut harvester in Bissau. These nuts, along with cashews and palm nuts, are among Guinea-Bissau's chief exports.

Higher Education. In the colonial era, only a handful of residents, primarily of Cape Verdean ancestry, went to Portugal for a higher education. Guineans in Senegal received degrees from French colonial institutions. During the revolution, many young people were sent to East Germany, the Soviet Union, Cuba, and China to be educated at the university and postgraduate level. After the revolution, the government was able to increase the literacy rate and the numbers of students who earned a high school diploma. Some of these students study in technical schools, but it is still necessary to go abroad for training in a university. Many students with such educations remain abroad.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Despite centuries of Catholic and Protestant missionary activity, few people claim to be Christian. The overwhelming majority (over 60 percent) of residents practice indigenous religions.

Rituals and Holy Places. The coastal groups believe that ancestor spirits exercise power over their living descendants, and those spirits are recognized in household shrines at which periodic offerings are made. In every village, there are dozens of shrines to tutelary or guardian spirits. These spirits are recognized at public ceremonies in which food and alcohol offerings are made and animals are sacrificed. Such spirits are thought to protect the community against misfortune. Individuals visit the shrines to request personal favors. Certain shrines have gained a transethnic reputation for reliability and power. Guineans abroad continue to return to those shrines and send money to pay for sacrifices and ceremonies.

Over 30 percent of Guineans are Moslem and recognize their allegiance to Islam through practices such as circumcision and fasting and various forms of Islamic mysticism.

Death and the Afterlife. The most elaborate and expensive life cycle rituals are associated with death, burial, and the enshrinement of ancestors.

Medicine and Health Care

Malaria and tuberculosis are rampant. Infant mortality rates are high and life expectancy is generally low because Western medicine is available only intermittently. Most residents seek out local healers, go to diviners, and make offerings at shrines. The government has made efforts to provide primary nursing care in the villages, but the country continues to rely on foreign doctors. There is a hospital in

Teenagers from Bijagos Islands playing the drums. Almost all children receive primary education in Guinea-Bissau.

the district capital of Canchungo that is run by Chinese medical personnel but also employs European doctors. Cubans once provided advance care in the hospital in Bissau.

Secular Celebrations

Independence Day, celebrated on 24 September, is the major national holiday. Carnival in Bissau, once a festival associated with Catholic Criolu culture, has become a multiethnic celebration.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. National television programming and radio programming provide some support for the arts.

Literature. Amilcar Cabral wrote extensively on the goals and theories of national liberation. His speeches are widely read today. Guineans of Cape Verdean ancestry such as Fausto Duarte, Terencio Anahory, and Joao Alves da Neves have begun to write fiction in Criolu. The Manjaco poet Antonio Baticam Ferreira has been published in Europe.

Graphic Arts. Art tends to be religious and traditional, and is made and used by villagers. There is not much of a market for tourist art, but Bijagos islanders produce carvings for the tourist markets.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

Until the civil war of 1998, there was a research program in Bissau called the Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas (INEP). During the war, the INEP building was damaged and its archives and library were vandalized.

Bibliography

Bigman, Laura. History and Hunger in West Africa: Food Production and Entitlement in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde, 1993.

Bowman, Joye. Ominious Transition: Commerce and Colonial Expansion in the Senegambia and Guinea, 1857– 1919, 1997.

Brooks, George E. Luso-African Commerce and Settlement in the Gambia and Guinea-Bissau Region, 1980.

Cann, John P. Counterinsurgency in Africa: The Portuguese Way of War, 1961–1974, 1997.

Forrest, Joshua. Guinea-Bissau: Power, Conflict, and Renewal in a West African Nation, 1992.

Galli, Rosemary, and Jocelyn Jones. Guinea-Bissau: Politics, Economics, and Society, 1987.

Lobban, Richard Andrew, Jr., and Peter Karibe Mendy. Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Guinea-Bissau, 3rd ed., 1999.

Lopes, Carlos. Guinea-Bissau: From Liberation Struggle to Independent Statehood, 1987.

Rodney, Walter. A History of the Upper Guinea Coast, 1545–1800, 1970.

Rudebeck, Lars. Guinea-Bissau: A Study in Political Mobilization, 1974.