Culture of Guatemala

Culture Name

Guatemalan

Alternative Name

Chapines

Orientation

Identification. The name Guatemala, meaning "land of forests," was derived from one of the Mayan dialects spoken by the indigenous people at the time of the Spanish conquest in 1523. It is used today by outsiders, as well as by most citizens, although for many purposes the descendants of the original inhabitants still prefer to identify themselves by the names of their specific language dialects, which reflect political divisions from the sixteenth century. The pejorative terms indio and natural have been replaced in polite conversation and publication by Indígena . Persons of mixed or non-indigenous race and heritage may be called Ladino , a term that today indicates adherence to Western, as opposed to indigenous, culture patterns, and may be applied to acculturated Indians, as well as others. A small group of African–Americans, known as Garifuna, lives on the Atlantic coast, but their culture is more closely related to those found in other Caribbean nations than to the cultures of Guatemala itself.

The national culture also was influenced by the arrival of other Europeans, especially Germans, in the second half of the nineteenth century, as well as by the more recent movement of thousands of Guatemalans to and from the United States. There has been increased immigration from China, Japan, Korea, and the Middle East, although those groups, while increasingly visible, have not contributed to the national culture, nor have many of them adopted it as their own.

Within Central America the citizens of each country are affectionately known by a nickname of which they are proud, but which is sometimes used disparagingly by others, much like the term "Yankee." The term "Chapín" (plural, "Chapines"), the origin of which is unknown, denotes anyone from Guatemala. When traveling outside of Guatemala, all its citizens define themselves as Guatemalans and/or Chapines. While at home, however, there is little sense that they share a common culture. The most important split is between Ladinos and Indians. Garifuna are hardly known away from the Atlantic coast and, like most Indians, identify themselves in terms of their own language and culture.

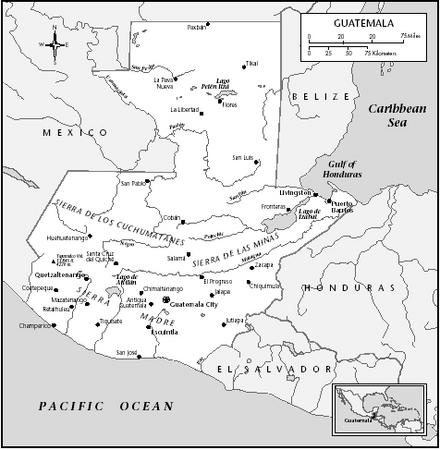

Location and Geography. Guatemala covers an area of 42,042 square miles (108,889 square kilometers) and is bounded on the west and north by Mexico; on the east by Belize, the Caribbean Sea, Honduras and El Salvador; and on the south by the Pacific Ocean. The three principal regions are the northern lowland plains of the Petén and the adjacent Atlantic littoral; the volcanic highlands of the Sierra Madre, cutting across the country from northwest to southeast; and the Pacific lowlands, a coastal plain stretching along the entire southern boundary. The country has a total of 205 miles (330 kilometers) of coastline. Between the Motagua River and the Honduran border on the southeast there is a dry flat corridor that receives less than forty inches (one hundred centimeters) of rain per year. Although the country lies within the tropics, its climate varies considerably, depending on altitude and rainfall patterns. The northern lowlands and the Atlantic coastal area are very warm and experience rain throughout much of the year. The Pacific lowlands are drier, and because they are at or near sea level, remain warm. The highlands are temperate. The coolest weather there (locally called "winter") occurs during the rainy season from May or June to November, with daily temperatures ranging from 50 to 60 degrees Fahrenheit in the higher altitudes, and from 60 to 70 degrees in Guatemala City, which is about a mile above sea level.

Guatemala

"Summer" denotes the period between February and May, when the temperature during the day in Guatemala City often reaches into the 80s.

The Spanish conquerors preferred the highlands, despite a difficult journey from the Atlantic coast, and that is where they placed their primary settlements. The present capital, Guatemala City, was founded in 1776 after a flood and an earthquake had destroyed two earlier sites. Although the Maya had earlier inhabited the lowlands of the Petén and the lower Motagua River, by the time the first Spaniards arrived, they lived primarily in the Pacific lowlands and western highlands. The highlands are still largely populated by their descendants. The eastern Motagua corridor was settled by Spaniards and is still inhabited primarily by Ladinos. Large plantations of coffee, sugarcane, bananas, and cardamom, all grown primarily for export, cover much of the Pacific lowlands. These are owned by large, usually nonresident, landholders and are worked by local Ladinos and Indians who journey to the coast from highland villages for the harvest.

Demography. The 1994 census showed a total of 9,462,000 people, but estimates for 1999 reached twelve million, with more than 50 percent living in urban areas. The forty-year period of social unrest, violence, and civil war (1956–1996) resulted in massive emigration to Mexico and the United States and has been estimated to have resulted in one million dead, disappeared, and emigrated. Some of the displaced have returned from United Nations refugee camps in Mexico, as have many undocumented emigrants to the United States.

The determination of ethnicity for demographic purposes depends primarily on language, yet some scholars and government officials use other criteria, such as dress patterns and life style. Thus, estimates of the size of the Indian population vary from 35 percent to more than 50 percent—the latter figure probably being more reliable. The numbers of the non-Mayan indigenous peoples such as the Garifuna and the Xinca have been dwindling. Those two groups now probably number less than five thousand as many of their young people become Ladinoized or leave for better opportunities in the United States.

Linguistic Affiliation. Spanish is the official language, but since the end of the civil war in December 1996, twenty-two indigenous languages, mostly dialects of the Mayan linguistic family, have been recognized. The most widely spoken are Ki'che', Kaqchikel, Kekchi, and Mam. A bilingual program for beginning primary students has been in place since the late 1980s, and there are plans to make it available in all Indian communities. Constitutional amendments are being considered to recognize some of those languages for official purposes.

Many Indians, especially women and those in the most remote areas of the western highlands, speak no Spanish, yet many Indian families are abandoning their own language to ensure that their children become fluent in Spanish, which is recognized as a necessity for living in the modern world, and even for travel outside one's village. Since the various indigenous languages are not all mutually intelligible, Spanish is increasingly important as a lingua franca . The Academy of Mayan Languages, completely staffed by Maya scholars, hopes its research will promote a return to Proto-Maya, the language from which all the various dialects descended, which is totally unknown today. Ladinos who grow up in an Indian area may learn the local language, but bilingualism among Ladinos is rare.

In the cities, especially the capital, there are private primary and secondary schools where foreign languages are taught and used along with Spanish, especially English, German, and French.

Symbolism. Independence Day (15 September) and 15 August, the day of the national patron saint, María, are the most important national holidays, and together reflect the European origin of the nation–state, as does the national anthem, "Guatemala Felíz" ("Happy Guatemala"). However, many of the motifs used on the flag (the quetzal bird and the ceiba tree); in public monuments and other artwork (the figure of the Indian hero Tecún Umán, the pyramids and stelae of the abandoned and ruined Mayan city of Tikal, the colorful motifs on indigenous textiles, scenes from villages surrounding Lake Atitlán); in literature (the novels of Nobel laureate Miguel Angel Asturias) and in music (the marimba, the dance called son) are associated with the Indian culture, even when some of their elements originated in Europe or in precolonial Mexico. Miss Guatemala, almost always a Ladina, wears Indian dress in her public appearances. Black beans, guacamole, tortillas, chili, and tamales, all of which were eaten before the coming of the Spaniards, are now part of the national culture, and have come to symbolize it for both residents and expatriates, regardless of ethnicity or class.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. Guatemala, along with other Central American Spanish colonies, declared its independence on 15 September 1821. Until 1839, it belonged first to Mexico and then to a federation known as the United Provinces of Central America. It was not until 1945 that a constitution guaranteeing civil and political rights for all people, including women and Indians, was adopted. However, Indians continued to be exploited and disparaged until recently, when international opinion forced Ladino elites to modify their attitudes and behavior. This shift was furthered by the selection of Rigoberta Menchú, a young Maya woman, for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1992.

Severe repression and violence during the late 1970s and 1980s was followed by a Mayan revitalization movement that has gained strength since the signing of the Peace Accords in 1996. While Mayan languages, dress, and religious practices have been reintroduced or strengthened, acculturation to the national culture has continued. Today more Indians are becoming educated at all levels, including postgraduate university training. A few have become professionals in medicine, engineering, journalism, law, and social work. Population pressure has forced many others out of agriculture and into cottage industries, factory work, merchandising, teaching, clerical work, and various white-collar positions in the towns and cities. Ironically, after the long period of violence and forced enlistment, many now volunteer for the armed forces.

Ethnic Relations. Some Ladinos see the Indian revitalization movement as a threat to their hegemony and fear that they will eventually suffer violence at Indian hands. There is little concrete evidence to support those fears. Because the national culture is composed of a blend of European and indigenous traits and is largely shared by Maya, Ladinos, and many newer immigrants, it is likely that the future will bring greater consolidation, and that social class, rather than ethnic background, will determine social interactions.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

The Spanish imposed a gridiron pattern on communities of all sizes, which included a central plaza, generally with a public water fountain known as a "pila," around which were situated a Catholic church, government offices, and the homes of high-ranking persons. Colonial homes included a central patio with living, dining, and sleeping rooms lined up off the surrounding corridors. A service patio with a pila and a kitchen with an open fireplace under a large chimney was located behind the general living area. Entrances were directly off the street, and gardens were limited to the interior patios.

Those town and house plans persist, except that homes of the elite now tend to be placed on the periphery of the town or city and have modified internal space arrangements, including second stories. An open internal patio is still popular, but gardens now surround the house, with the whole being enclosed behind high walls. The older, centrally located colonial houses are now occupied by offices or have been turned into rooming houses or hotels.

Indian towns retain these characteristics, but many of the smaller hamlets exhibit little patterning. The houses—mostly made of sun-dried bricks (adobe) and roofed with corrugated aluminum or ceramic tiles—may stretch out along a path or be located on small parcels of arable land. The poorest houses often have only one large room containing a hearth; perhaps a bed, table and chairs or stools; a large ceramic water jug and other ceramic storage jars; a wooden chest for clothes and valuables; and sometimes a cabinet for dishes and utensils. Other implements may be tied or perched on open rafters in baskets. The oldest resident couple occupies the bed, with children and younger adults sleeping on reed mats ( petates ) on the floor; the mats are rolled up when not in use. Running water in the home or yard is a luxury that only some villages enjoy. Electricity is widely available except in the most remote areas. Its primary use is for light, followed by refrigeration and television.

The central plazas of smaller towns and villages are used for a variety of purposes. On market days, they are filled with vendors and their wares; in the heat of the day people will rest on whatever benches may be provided; in early evening young people may congregate and parade, seeking partners of the opposite sex, flirting, and generally having a good time. In Guatemala City, the central plaza has become the preferred site for political demonstrations.

The national palace faces this central plaza; although it once was a residence for the president, today it is used only for official receptions and meetings with dignitaries. More than any other building, it is a symbol of governmental authority and power. The walls of its entryway have murals depicting scenes honoring the Spanish and Mayan heritages. Other government buildings are scattered throughout the central part of Guatemala City; some occupy former residences, others are in a newer complex characterized by modern, massive, high-rising buildings of seven or eight floors. Some of these structures are adorned on the outside with murals depicting both Mayan and European symbols.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Corn made into tortillas or tamales, black beans, rice, and wheat in the form of bread or pasta are staples eaten by nearly all Guatemalans. Depending on their degree of affluence, people also consume chicken, pork, and beef, and those living near bodies of water also eat fish and shellfish. With improvements in refrigeration and transport, seafood is becoming increasingly popular in Guatemala City. The country has long been known for vegetables and fruits, including avocados, radishes, potatoes, sweet potatoes, squash, carrots, beets, onions, and tomatoes. Lettuce, snow peas, green beans, broccoli, cauliflower, artichokes, and turnips are grown for export and are also available in local markets; they are eaten more by Ladinos than by Indians. Fruits include pineapples,

People walk past fast-food restaurants in Guatemala City, Guatemala. "Fast food" is a fairly recent addition to traditional Guatemalan diets.

papayas, mangoes, a variety of melons, citrus fruits, peaches, pears, plums, guavas, and many others of both native and foreign origin. Fruit is eaten as dessert, or as a snack in-between meals.

Three meals per day are the general rule, with the largest eaten at noon. Until recently, most stores and businesses in the urban areas closed for two to three hours to allow employees time to eat at home and rest before returning to work. Transportation problems due to increased traffic, both on buses and in private vehicles, are bringing rapid change to this custom. In rural areas women take the noon meal to the men in the fields, often accompanied by their children so that the family can eat as a group. Tortillas are eaten by everyone but are especially important for the Indians, who may consume up to a dozen at a time, usually with chili, sometimes with beans and/or stews made with or flavored with meat or dried shrimp.

Breakfast for the well to do may be large, including fruit, cereal, eggs, bread, and coffee; the poor may drink only an atol , a thin gruel made with any one of several thickeners—oatmeal, cornstarch, cornmeal, or even ground fresh corn. Others may only have coffee with sweet bread. All drinks are heavily sweetened with refined or brown sugar. The evening meal is always lighter than that at noon.

Although there are no food taboos, many people believe that specific foods are classified as "hot" or "cold" by nature, and there may be temporary prohibitions on eating them, depending upon age, the condition of one's body, the time of day, or other factors.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. The ceremonial year is largely determined by the Roman Catholic Church, even for those who do not profess that faith. Thus, the Christmas period, including Advent and the Day of the Kings on 6 January, and Easter week are major holidays for everyone. The patron saints of each village, town or city are honored on their respective days. The cofradia organization, imposed by the colonial Spanish Catholic Church, is less important now, but where it persists, special foods are prepared. Tamales are the most important ceremonial food. They are eaten on all special occasions, including private parties and celebrations, and on weekends, which are special because Sunday is recognized as being a holy day, as well as a holiday. A special vegetable and meat salad called fiambre is eaten on 1 November, the Day of the Dead, when families congregate in the cemeteries to honor, placate, and share food with deceased relatives. Codfish cooked in various forms is eaten at Easter, and Christmas is again a time for gourmet tamales and ponche , a rum-based drink containing spices and fruits. Beer and rum, including a fairly raw variety known as aguardiente are the most popular alcoholic drinks, although urban elites prefer Scotch whisky.

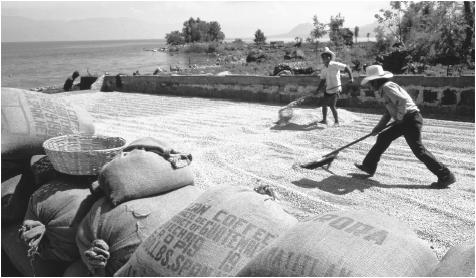

Basic Economy. Guatemala's most important resource is its fertile land, although only 12 percent of the total landmass is arable. In 1990, 52 percent of the labor force was engaged in agriculture, which contributed 24 percent of the gross domestic product. Although both Ladinos and Indians farm, 68 percent of the agricultural labor force was Indian in 1989. Forty-seven percent of Indian men were self-employed as farmers, artisans, or merchants; the average income for this group was only about a third of that for Ladino men. Agriculture accounts for about one-fourth of the gross domestic product.

The country has traditionally produced many agricultural products for export, including coffee, sugar, cardamom, bananas, and cotton. In recent years flowers and vegetables have become important. However, Guatemala is not self-sufficient in basic grains such as wheat, rice, and even maize, which are imported from the United States. Many small farmers, both Indian and Ladino, have replaced traditional subsistence crops with those grown for export. Although their cash income may be enhanced, they are forced to buy more foods. These include not only the basic staples, but also locally produced "junk" foods such as potato chips and cupcakes as well as condiments such as mayonnaise.

Affluent city dwellers and returning expatriates increasingly buy imported fruits, vegetables, and specialty items, both raw and processed. Those items come from neighboring countries such as Mexico and El Salvador as well as from the United States and Europe, especially Spain, Italy, and France.

Land Tenure and Property. The concept of private property in land, houses, tools, and machinery is well established even though most Indian communities have long held some lands as communal property that is allotted as needed. Unfortunately, many rural people have not registered their property, and many swindles occur, leading to lengthy and expensive lawsuits. As long as owners occupied their land and passed it on to their children or other heirs, there were few problems, but as the population has become more mobile, the number of disputes has escalated. Disputes occur within villages and even within families as individuals move onto lands apparently abandoned while the owners are absent. Sometimes the same piece of land is sold two

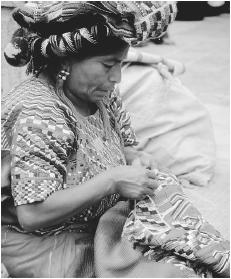

A woman embroidering in Antigua. Handicrafts have been produced and widely traded in Guatemala for centuries.

or more times to different outside persons, often speculators from urban areas who discover the fraud only when they find another person occupying the land. Some land disputes have occurred when agents of the government have illegally confiscated property belonging to Indian communities. In other cases, homeless peasants have taken over unused land on large private plantations and government reserves.

Commercial Activities. Agricultural products are the goods most commonly produced for sale within the country and for export. Handicrafts have been produced and widely traded since precolonial times and are in great demand by tourists, museums, and collectors, and are increasingly exported through middlemen. The most sought after items include hand woven cotton and woolen textiles and clothing items made from them; baskets; ceramics; carved wooden furniture, containers, utensils and decorative items; beaded and silver jewelry; and hand-blown glassware. These items are made in urban and rural areas by both Ladinos and Indians in small workshops and by individuals in their own homes.

Assembly plants known as maquilas produce clothing and other items for export, using imported materials and semiskilled labor. Despite criticisms of this type of enterprise in the United States, many Guatemalans find it a welcome source of employment with relatively high wages.

Major Industries. Guatemala has many light industries, most of which involve the processing of locally grown products such as chicken, beef, pork, coffee, wheat, corn, sugar, cotton, cacao, vegetables and fruits, and spices such as cinnamon and cardamom. Beer and rum are major industries, as is the production of paper goods. A large plastics industry produces a wide variety of products for home and industrial use. Several factories produce cloth from domestic and imported cotton. Some of these products are important import substitutes, and others are exported to other Central American countries and the United States.

Division of Labor. In the Ladino sector, upper-class men and women work in business, academia, and the major professions. Older Ladino and Indian teenagers of both sexes are the primary workers in maquilas , a form of employment that increasingly is preferred to working as a domestic. Children as young as four or five years work at household tasks and in the fields in farming families. In the cities, they may sell candies or other small products on the streets or "watch" parked cars. Although by law all children must attend school between ages seven and thirteen, many do not, sometimes because there is no school nearby, because the child's services are needed at home, or because the family is too poor to provide transportation, clothing, and supplies. The situation is improving; in 1996, 88 percent of all children of primary age were enrolled in school, although only 26 percent of those of high school age were enrolled.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. Social class based on wealth, education, and family prestige operates as a sorting mechanism among both Indians and Ladinos. Race is also clearly a component, but may be less important than culture and lifestyle, except in the case of the black Garifuna, who are shunned by all other groups. Individual people of Indian background may be accepted in Ladino society if they are well educated and have the resources to live in a Western style. However, Indians as a group are poorer and less educated than are non-Indians. In the 1980s, illiteracy among Indians was 79 percent, compared with 40 percent among Ladinos. In 1989, 60 percent of Indians had no formal education, compared with 26 percent of Ladinos. Indians with thirteen or more years of education earned about one-third less than did Ladinos with a comparable level of education.

Symbols of Social Stratification. Dress varies significantly by class and caste. Professional and white-collar male workers in the cities usually wear suits, dress shirts, and neckties, and women in comparable pursuits dress fashionably, including stockings and high-heeled shoes. Nonemployed upper-class women dress more casually, often in blue jeans and T-shirts or blouses. They frequent beauty salons since personal appearance is considered an important indicator of class.

Poorer Ladinos, whether urban or rural, buy secondhand clothing from the United States that is sold at low prices in the streets and marketplaces. T-shirts and sweatshirts with English slogans are ubiquitous.

Many Mayan women, regardless of wealth, education, or residence, continue to wear their distinctive clothing: a wraparound or gathered, nearly ankle-length skirt woven with tie-dyed threads that produce interesting designs, topped with a cotton or rayon blouse embroidered with flower motifs about the neck, or a more traditional huipil . The huipil is hand woven on a backstrap loom and consists of two panels sewn together on the sides, leaving openings for the arms and head. It usually is embroidered with traditional designs. Shoes or sandals are almost universal, especially in towns and cities. Earrings, necklaces, and rings are their only jewelry.

Indian men are more likely to dress in a Western style. Today's fashions dictate "cowboy" hats, boots, and shirts for them and for lower-class rural Ladinos. In the more remote highland areas, many men continue to wear the clothing of their ancestors. The revitalization movement has reinforced the use of traditional clothing as a means of asserting one's identity.

Political Life

Government. As of 1993, the president and vice-president and sixteen members of the eighty-member congress are elected by the nation as a whole for non-renewable four-year terms, while the remaining sixty-four members of the unicameral legislature are popularly elected by the constituents of their locales. Despite universal suffrage, only a small percentage of citizens vote.

There are twenty-two departments under governors appointed by the president. Municipalities are autonomous, with locally elected officials, and are funded by the central government budget. In areas with a large Mayan population, there have been two sets of local government leaders, one Ladino and one Mayan, with the former taking precedence. In 1996, however, many official or "Ladino" offices were won by Maya.

Leadership and Political Officials. Political parties range from the extreme right to the left and represent varying interests. Thus, their numbers, size, and electoral success change over time. It generally is believed that most elected officials use their short periods in office to aggrandize their prestige and line their pockets. Most take office amid cheering and accolades but leave under a cloud, and many are forced to leave the country or choose to do so. While in office, they are able to bend the law and do favors for their constituents or for foreigners who wish to invest or do business in the country. Some national business gets accomplished, but only after lengthy delays, debate, and procrastination.

Social Problems and Control. Since the signing of the Peace Accords in December 1996, there has been continued social unrest and a general breakdown in the system of justice. Poverty, land pressure, unemployment, and a pervasive climate of enmity toward all "others" have left even rural communities in a state of disorganization. In many Maya communities, their traditional social organization having been disrupted or destroyed by the years of violence, the people now take the law into their own hands. Tired of petty crime, kidnappings, rapes, and murders and with no adequate governmental relief, they frequently lynch suspected criminals. In the cities, accused criminals frequently are set free for lack of evidence, since the police and judges are poorly trained, underpaid, and often corrupt. Many crimes are thought to have been committed by the army or by underground vigilante groups unhappy with the Peace Accords and efforts to end the impunity granted to those who committed atrocities against dissidents.

Military Activity. In 1997, the army numbered 38,500. In addition, there is a paramilitary national police force of 9,800, a territorial militia of about 300,000, and a small navy and air force.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

Guatemala has governmental and nongovernmental agencies that promote change in agriculture, taxes, banking, manufacturing, environmental protection, health, education, and human and civil rights.

Since 1945 the government has provided social security plans for workers, but only a small percentage of the populace has received these health and retirement benefits. There are free hospitals and clinics throughout the country, although many have inadequate equipment, medicines, and personnel. Free or inexpensive health services are offered as charities through various churches and by private individuals.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. Among both Maya and Ladinos, women are associated primarily with the domestic world and men work in agriculture, business, and manufacturing. However, well-educated professional women are accepted and often highly respected; many are owners and managers of businesses. More of these women are Ladinas than Mayas. Statistically, women are less educated and lower paid than their male counterparts. Their numbers exceed those of males in nursing, secretarial, and clerical jobs. The teaching force at all levels has attracted women as well as men, but men predominate.

In rural areas, Maya women and men may engage in agriculture, but the crops they grow are different. Men tend to grow basic grains such as corn and beans as well as export crops such as green beans and snow peas. Women grow vegetables and fruits for local consumption and sale, as well as herbs and spices.

Handicrafts also tend to be assigned according to gender. Pottery is most often made by Indian women and Ladino men. Similarly, Indian women are the only ones who weave on backstrap or stick looms, while both Indian and Ladino men weave on foot looms. Indian men knit woolen shoulder bags for their own use and for sale. Men of both ethnicities do woodwork and carpentry, bricklaying, and upholstering. Indian men carve images of saints, masks, slingshots, and decorative items for their own use or for sale. Men and boys fish, while women and girls as well as small boys gather wild foods and firewood. Women and children also tend sheep and goats.

Rural Ladinas do not often engage in agriculture. They concentrate on domestic work and cottage industries, especially those involving sewing, cooking, and processing of foods such as cheese,

A market set up in front of the church in Chichicastenango, Guatemala. Market-based commerce is still a vital part of the Guatemalan economy.

breads, and candies for sale along the highways or in the markets.

The Relative Status of Men and Women. Indian and poor Ladino women (as well as children) are often browbeaten and physically mistreated by men. Their only recourse is to return to their parents' home, but frequently are rejected by the parents for various reasons. A woman from a higher-status family is less likely to suffer in this way, especially if her marriage has been arranged by her parents. While walking, a Maya woman traditionally trails her husband; if he falls drunk by the wayside, she dutifully waits to care for him until he wakes up.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Marriages are sometimes arranged in Maya communities, although most couples choose each other and often elope. Membership in private clubs and attendance at private schools provides a way for middle-class and upper-class young people to meet prospective mates. Parents may disapprove of a selection, but their children are likely able to persuade them. Marriages are celebrated in a civil ceremony that may be followed by a religious rite. Monogamy is the rule, although many men have a mistress as well as a wife. Among the poorer classes, both Mayan and Ladino, unions are free and ties are brittle; many children do not know, nor are they recognized by their fathers. Formal divorces are more common than many people believe, despite the disapproval of the Catholic Church. Until recently, a divorced woman did not have the right to retain her husband's surname; but she may sue for a share of his property to support herself and her minor children.

Domestic Unit. The nuclear family is the preferred and most common domestic unit. Among both Ladinos and Maya, a young couple may live at first in the home of the man's parents, or if that is inconvenient or overcrowded, with the parents of the woman. Wealthy Ladinos often provide elaborate houses close to their own homes as wedding presents for their sons and daughters.

Inheritance. Inheritance depends on a witnessed written or oral testament of the deceased, and since many people die without indicating their preferences, family disputes after death are very common among both Mayas and Ladinos. Land, houses, and personal belongings may be inherited by either sex, and claims may be contested in the courts and in intrafamily bickering.

A woman carries baskets of textiles along a street in Antigua. Guatemalan textiles are highly regarded for their quality.

Socialization

Infant Care. The children of middle-class and upper-class Ladinos are cared for by their mothers, grandmothers, and young women, often from the rural areas, hired as nannies. They tend to be indulged by their caretakers. They may be breastfed for a few months but then are given bottles, which they may continue using until four or five years. To keep children from crying or complaining to their parents, nannies quickly give them whatever they demand.

Maya women in the rural areas depend upon their older children to help care for the younger ones. Babies are breastfed longer, but seldom after two years of age. They are always close to their mothers during this period, sleeping next to them and carried in shawls on their backs wherever they go. They are nursed frequently on demand wherever the mother may be. Little girls of five or six years may be seen carrying tiny babies in the same way in order to help out, but seldom are they out of sight of the mother. This practice may be seen as education for the child as well as caretaking for the infant. Indian children are socialized to take part in all the activities of the family as soon as they are physically and mentally capable.

Child Rearing and Education. Middle-class and upper-class Ladino children, especially in urban areas, are not expected to do any work until they are teenagers or beyond. They may attend a private preschool, sometimes as early as eighteen months, but formal education begins at age seven. Higher education is respected as a means of rising socially and economically. Children are educated to the highest level of which they are capable, depending on the finances of the family.

Higher Education. The national university, San Carlos, has until recently had free tuition, and is still the least expensive. As a result, it is overcrowded, but graduates many students who would not otherwise be able to attain an education. There are six other private universities, several with branches in secondary cities. They grant undergraduate and advanced degrees in the arts, humanities, and sciences, as well as medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, law, engineering, and architecture. Postgraduate work is often pursued abroad by the better and more affluent students, especially in the United States, Spain, Mexico, and some other Latin American countries.

Etiquette

Etiquette varies considerably according to ethnicity. In the past, Indians were expected to defer to Ladinos, and in general they showed them respect and subservience at all times. In turn, they were treated by Ladinos as children or as persons of little worth. Some of those modes of behavior carried over into their own society, especially within the cofradia organization, where deliberate rudeness is considered appropriate on the part of the highest-ranking officers. Today there is a more egalitarian attitude on both sides, and in some cases younger Maya may openly show contempt for non-indigenous people. Maya children greet adults by bowing their heads and sometimes folding their hands before them, as in prayer. Adults greet other adults verbally, asking about one's health and that of one's family. They are not physically demonstrative.

Among Ladino urban women, greetings and farewells call for handshakes, arm or shoulder patting, embraces, and even cheek kissing, almost from first acquaintance. Men embrace and cheek kiss women friends of the family, and embrace but do not kiss each other. Children are taught to kiss all adult relatives and close acquaintances of their parents hello and goodbye.

In the smaller towns and until recently in the cities, if eye contact is made with strangers on the street, a verbal "good morning" or "good afternoon" is customary.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Roman Catholicism, which was introduced by the Spanish and modified by Maya interpretations and syncretism, was almost universal in Guatemala until the early part of the twentieth century, when Protestantism began to make significant headway among both Ladinos and Maya. Today it has been estimated that perhaps 40 percent or more adhere to a Protestant church or sect ranging from established churches with international membership to small local groups celebrating their own set of beliefs under the leadership of lay pastors.

Many Maya combine membership in a Christian fellowship with a continued set of beliefs and practices inherited from their ancient ancestors. Rituals may still be performed to ensure agricultural success, easy childbirth, recovery from illness, and protection from the elements (including eclipses) and to honor and remember the dead. The Garifuna still practice an Afro-Caribbean form of ancestor worship that helps to meld together families broken by migration, plural marriages, and a social environment hostile to people of their race and culture.

Many of the indigenous people believe in spirits of nature, especially of specific caves, mountains, and bodies of water, and their religious leaders regularly perform ceremonies connected with these sites. The Catholic Church has generally been more lenient in allowing or ignoring dual allegiances than have Protestants, who tend to insist on strict adherence to doctrine and an abandonment of all "non-Christian" beliefs and practices, including Catholicism.

Medicine and Health Care

Although excellent modern medical care is available in the capital city for those who can afford it and even for the indigent, millions of people in the rural areas lack adequate health care and health education. The medical training at San Carlos University includes a field stint for advanced students in rural areas, and often these are the only well-trained medical personnel on duty at village-level government-run health clinics.

The less well educated have a variety of folk explanations and cures for disease and mental illnesses, including herbal remedies, dietary adjustments, magical formulas, and prayers to Christian saints, local gods, and deceased relatives.

Most births in the city occur in hospitals, but some are attended at home by midwives, as is more usual in rural areas. These practitioners learn their skills from other midwives and through government-run courses.

For many minor problems, local pharmacists may diagnose, prescribe, and administer remedies, including antibiotics.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. The Ministry of Culture provides moral and some economic support for the arts, but most artists are self-supporting. Arts and handicrafts are important to all sectors of the population; artists are respected and patronized, especially in the cities where there are numerous art galleries. Even some of the smaller towns, such as Tecpán, Comalapa and Santiago de Atitlán offer paintings by local artists for sale to both foreign and Guatemalan visitors. There are dozens, perhaps hundreds, of indigenous "primitive" painters, some of whom are known internationally. Their products form an important part of the wares offered to tourists and local collectors. Non-indigenous painters are exhibited primarily in the capital city; these include many foreign artists as well as Guatemalans.

Graphic Arts. Textiles, especially those woven by women on the indigenous backstrap loom, are of such fine quality as to have been the object of scholarly study. The Ixchel Museum of Indian Textiles, located in Guatemala City at the Francisco

Men spread out coffee beans to dry them in the sun alongside Lake Atitlan. Agriculture is generally considered a male endeavor, although Maya women may grow vegetables and fruits for local sale and consumption.

Marroquín University, archives, preserves, studies, and displays textiles from all parts of the country.

Pottery ranges from utilitarian to ritual wares and often is associated with specific communities, such as Chinautla and Rabinal, where it has been a local craft for centuries. There are several museums, both government and private, where the most exquisite ancient and modern pieces are displayed.

Performance Arts. Music has been important in Guatemala since colonial times, when the Catholic Church used it to teach Christian doctrine. Both the doctrine and the musical styles were adopted at an early date. The work of Maya who composed European-style classical music in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries has been revived and is performed by several local performance groups, some using replicas of early instruments. William Orbaugh, a Guatemalan of Swiss ancestry, is known internationally for performances of classical and popular guitar music. Garifuna music, especially that of Caribbean origin, is popular in both Guatemala and in the United States, which has a large expatriate Garifuna population. Other popular music derives from Mexico, Argentina, and especially the United States. The marimba is the popular favorite instrument, in both the city and in the countryside.

There is a national symphony as well as a ballet, national chorus, and an opera company, all of which perform at the National Theater, a large imposing structure built on the site of an ancient fort near the city center.

Theater is less developed, although several private semiprofessional and amateur groups perform in both Spanish and English. The city of Antigua Guatemala is a major center for the arts, along with the cities of Guatemala and Quetzaltenango.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

Although the country boasts six universities, none is really comprehensive. All of the sciences are taught in one or another of these, and some research is done by professors and advanced students— especially in fields serving health and agricultural interests, such as biology, botany, and agronomy. Various government agencies also conduct research in these fields. However, most of those doing advanced research have higher degrees from foreign universities. The professional schools such as Dentistry, Nutrition, and Medicine keep abreast of modern developments in their fields, and offer continuing short courses to their graduates.

Anthropology and archaeology are considered very important for understanding and preserving the national cultural patrimony, and a good bit of research in these fields is done, both by national and visiting scholars. One of the universities has a linguistics institute where research is done on indigenous languages. Political science, sociology, and international relations are taught at still another, and a master's degree program in development, depending on all of the social sciences, has recently been inaugurated at still a third of the universities. Most of the funding available for such research comes from Europe and the United States, although some local industries provide small grants to assist specific projects.

Bibliography

Adams, Richard N. Cultural Surveys of Panama, Nicaragua, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras , 1957.

Asturias, Miguel Angel. Men of Maize , 1994.

——. The Mirror of Lida Sal: Tales Based on Mayan Myths and Guatemalan Legends , 1997.

Asturias de Barrios, Linda, ed. Cuyuscate: The Traditional Brown Cotton of Guatemala , 2000.

Aveni, Anthony F. The Sky in Mayan Literature , 1995.

Bahl, Roy W., et al. The Guatemalan Tax Reform , 1996.

Carlsen, Robert S. The War for the Heart and Soul of a Highland Maya Town , 1997.

Carmack, Robert. Rebels of Highland Guatemala: The Quiche-Mayas of Momostenango , 1995.

——, ed. Harvest of Violence , 1988.

Ehlers, Tracy B. Silent Looms: Women, Work, and Poverty in a Guatemalan Town , 1989.

Fischer, Edward F., and R. McKenna Brown, eds. Maya Cultural Activism in Guatemala , 1996.

Flannery, Kent, ed. Maya Subsistence , 1982.

Garrard, Virginia. A History of Protestantism in Guatemala , 1998.

Garzon, Susan, ed. The Life of Our Language: Kaqchikel Maya Maintenance, Shift and Revitalization , 1998.

Goldin, C. "Work and Ideology in the Maya Highlands of Guatemala: Economic Beliefs in the Context of Occupational Change." Economic Development and Cultural Change 41(1):103–123, 1992.

Goldman, Francisco. The Long Night of White Chickens , 1993.

Gonzalez, Nancie L. Sojourners of the Caribbean: Ethnogenesis and Ethnohistory of the Garifuna , 1988.

Handy, J. Gift of the Devil: A History of Guatemala , 1984.

Hendrickson, Carol. Weaving Identities: Construction of Dress and Self in a Highland Guatemalan Town , 1995.

McCreery, David. Rural Guatemala, 1760–1940 , 1994.

Menchú, Rigoberta, and Ann Wright (ed.). Crossing Borders , 1998.

Nash, June, ed. Crafts in the World Market: The Impact of Global Exchange on Middle American Artisans , 1993.

Perera, Victor. Unfinished Conquest: The Guatemalan Tragedy , 1993. Psacharopoulos, George. "Ethnicity, Education and Earnings in Bolivia and Guatemala," Comparative Education Review 37(1):9–20, 1993.

Reina, Ruben E. and Robert M. Hill II. The Traditional Pottery of Guatemala , 1978.

Romero, Sergio Francisco and Linda Asturias de Barrios. "The Cofradia in Tecpán During the Second Half of the Twentieth Century." In Linda Asturias de Barrios, ed. Cuyuscate: The Traditional Brown Cotton of Guatemala , 2000.

Scheville, Margot Blum, and Christopher H. Lutz (designer). Maya Textiles of Guatemala , 1993.

Smith, Carol, ed. Guatemalan Indians and the State: 1540 to 1988 , 1992.

Steele, Diane. "Guatemala." In Las poblaciones indígenas y. la pobreza en América Latina: Estudio Empírico , 1999.

Stephen, D. and P. Wearne. Central America's Indians , 1984.

Tedlock, Barbara. Time and the Highland Maya , 1990.

Tedlock, Dennis. Popul Vuh: The Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of the Gods and Kings , 1985.

Urban, G. and J. Sherzer, eds. Nation–States and Indians in Latin America , 1992.

Warren, Kay B. Indigenous Movements and Their Critics: Pan-Maya Activism in Guatemala , 1998.

Watanabe, John. Maya Saints and Souls in a Changing World , 1992.

Whetten, N. L. Guatemala, The Land and the People , 1961.

Woodward, R. L. Guatemala , 1992.

World Bank. World Development Indicators , 1999.