Culture of Yemen

Culture Name

Yemeni

Alternative Names

South Arabian, al-Yamani

Orientation

Identification. The name of the country is derived from the legendary ancestor Yaman, the son of Qahtan, or from the Arabic root ymn ("the right") since Yemen is located to the right of the Meccan sanctuary of Kaaba. Some scholars compare the Arabic word yumna ("happy") with the Roman name for the southwest Arabia, Arabia Felix ("Happy Arabia"). Inhabitants feel that they have a common culture, although local and class identities are still important.

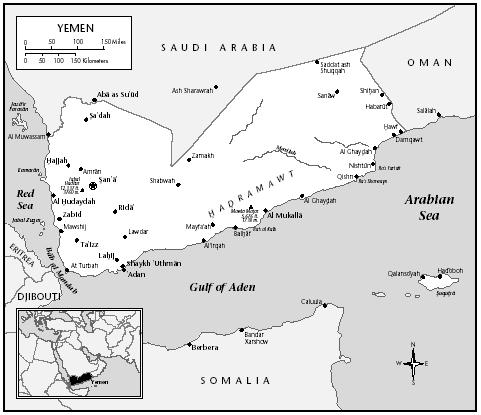

Location and Geography. Medieval Arab geographers thought of Yemen as covering the entire southern strip of the Arabian peninsula, from the mountainous southwest, including Najran and Asir, to Hadhramaut and Oman on the east. Today that area includes the regions that make up the Republic of Yemen (RY), which was formed in 1990 when the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR, or North Yemen) with its capital in Sana'a, and the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY, or South Yemen), with its capital in Aden, were unified. The capital is Sana'a, and Aden is referred to as the country's economic capital. The approximate size of the nation, since some of its borders are not demarcated, is 187,000 square miles (North: 75,000 square miles; South: 112,000 square miles), or 482,100 square kilometers.

There are six cultural and economic zones. The Tihama, a coastal plain and hilly area along the Red Sea, is fifteen to twenty-five miles (twenty-five to forty kilometers) wide. It is an area of fishing, commerce, and trade in the ports of al-Mukha (Mocha) and al-Hudayda as well as agriculture in oases (the main crops are millet, maize, sugarcane, watermelons, tobacco, and cotton) as well as livestock breeding. Handicrafts are made in Zabid, Bayt al-Faqih, and other centers. The highlands in the west have regular seasonal rains. Terraced agriculture (millet, wheat, barley, grapes, coffee, tobacco, vegetables, fruits, qat) is practiced, and goats, sheep, cows, and donkeys are raised. The central mountains consist of wide plateaus and basins. Fields are watered from wells and rainfall is sufficient for most crops. This region includes urban centers such as Sana'a and Sa'da. The high plateau in the east gradually merges with the desert Rub al-Khal . Date palms are cultivated in small oases, and the population is semi nomadic. There are salt deposits near Shabwa, Safir, and Harib. The limestone tableland of Hadhramaut and Wadi Masila has valleys (wadis) carved deep into the plateau. Cultivated patches are irrigated with rain and flood waters and from wells. Hinterlands towns include Shibam, Sayun, and Tarim in the Inner Wadi, and there are seaports at al-Mukalla and al-Shihr. The adjacent Mahra province and Socotra island are culturally related to this zone. The Gulf of Aden coastal plain, which is five to ten miles (eight to sixteen kilometers) wide, is discontinuous. Its ports, from Aden in the west to Sayhut and al-Ghayda in the east, are connected with the inland regions rather than with one another.

Demography. The population is ethnically Arab, divided between Sunni Muslims of the Shafi'i school and Shi'a Muslims of the Zaydi school. There are small groups of Jews, Hindus, and Christians. In 1949 and 1950, about fifty thousand Yemeni Jews left for Israel. In 1998, the population was 17,071,000. The annual growth rate is limited by migration and a high infant mortality rate. The birthrate is high, and almost half the population is under fifteen years of age.

Linguistic Affiliation. Yemenis speak Arabic, which belongs to the Semitic language family. Classical

Yemen

Arabic, the language of Islam and the Koran, is used on formal occasions. The spoken dialects, whose areas roughly correspond to the six cultural zones, are used in everyday life. Some groups have maintained their ancient oral tongues of the south Arabic branch. The most commonly used foreign language is English, and Russian is still understood in Sana'a and Aden.

Symbolism. The notion of allegiance is shaped by kinship, the native land, language, faith, and a shared culture. The symbol of male honor is a curved dagger, the jambiyyah ; lineage is symbolized by a clan's tower at the top of a hill; and generosity and hospitality are expressed in making and serving coffee. The coffee tree, the state eagle, the national colors, and the Marib Dam are shown in the new national emblem. The colors of the national flag (horizontal bands of red, white, and black) reflect pan-Arab symbolism, being similar to the flags of Syria, Iraq, and Egypt. The national anthem and national days of celebration emphasize the unification of the country.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. The ancient walled city Sana'a is said to be the oldest city in the world, founded by Noah's eldest son, Shem, the forefather of Qahtan. Bilqis, the Queen of Sheba (Saba), is mentioned in the Bible and the Koran. The kingdom of Saba, with its capital, Marib, had existed since the first millennium B.C.E. The Marib Dam provided irrigation for about twenty-five thousand acres of

Most Yemenis are urban dwellers or sedentary agriculturalists.

arable land; its collapse in the first centuries C.E. is depicted in the Koran as a punishment from God. The prosperity of the principal rival kingdoms, Saba, Hadhramaut, Awsan, Qataban, and Ma'in, was based on the cultivation and overland exportation of frankincense, myrrh, and spices to the Mediterranean. Ancient South Arabian culture developed an intricate architecture and created masterpieces of figurative and decorative arts. It maintained contacts with Egypt, Greece, Palmyra, Chaldea, and Abyssinia, which was founded by Sabaeans, as well as India. In 25–24 B.C.E. , the Roman emperor attempted to conquer the Sabaean kingdom, which was the southernmost outlet of the trade route to India. At that time, caravan traffic became less important than the shipping route between Egypt and India. The whole of southwestern Arabia was united by the kingdom of Himyar (circa 100 B.C.E. – 525 C.E. , which controlled the Red Sea and the coasts of the Gulf of Aden. After the fall of Jerusalem in 70 C.E. , many Jews settled in the region, and the Christian (Nestorian) faith was propagated. In the early sixth century, the kings of Himyar converted to Judaism and persecuted local Christians, leading the Abyssinians to take control of South Arabia in 525. The Persian Sassanians followed in 575.

The advent of Islam to South Arabia in the seventh century ousted local pantheons and monotheistic cults. Yemeni tribes took an active part in the Arab conquests and the construction of an Islamic state, and the tribal principal became a distinct form of communal organization in the area. In 898, al-Hadi Yahya proclaimed himself the first Zaydi imam, establishing a Shi'a dynasty that ruled in several regions of northern Yemen until 1962. The Egyptian Ayyubids invaded in 1173 and controlled all of Yemen until 1228. Their local vassals, the Rasulids, ruled until 1454, the golden age of art, science, and prosperity. The Tahirid tribesmen succeeded the Rasulids but were overthrown by the Egyptian Mamluks (1515–1517), who opened Yemen to invasion by the Ottoman Turks.

The Portuguese, the French, and the British as well as the Ottoman Empire tried to seize the main routes to the Indian Ocean. The local coffee mocha (named after the town al-Mukha), became an important item in world trade. The split of Yemen into the south and the north was caused by British and Ottoman politics. In 1839, the British occupied Aden. The Ottomans took control over main regions of the north in 1848–1872 in spite of armed resistance by the Zaydi imams, who had defeated the Turks in 1568, 1613, and 1635. Frequent uprisings forced the Ottomans to grant autonomy to the Zaydi regions in 1911. After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in 1918, the Turks withdrew from the north; its independence under the Zaydi imams was internationally recognized in 1923. The imams claimed the right to all of historical Yemen but ceded the province of Najran to Saudi Arabia in 1934. In 1962, the rule of imams was overthrown, and YAR was paroclaimed.

The South was administered by British Bombay presidency until 1937, when it was designated the Crown Colony of Aden and Protectorate. In 1963, the Aden Colony became part of the British-sponsored Federation of South Arabia, which was scheduled to become independent in 1968. The British had to withdraw in 1967, and power was seized by the Marxist-oriented National Liberation Front. The south was proclaimed the People's Republic of South Yemen in 1967 and the PDRY in 1970. The tribal, religious, and pro-Western YAR and the Marxist, secular, and pro-communist PDRY engaged in border warfare in 1979 and 1987. In 1989, the YAR and the PDRY signed a draft document for unification. On 22 May 1990 the new Yemeni nation was born. Six months after unification, the Gulf War started. Yemeni labor migrants from the Arab oil states were forced to return home, causing a population increase, a slowdown in the migrants' remittances, and a reduction in foreign aid.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

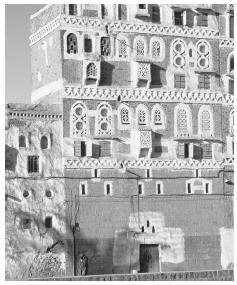

Apart from a relatively few pastoral nomads who live in tents or caves, most residents are urban dwellers (one-fourth) and sedentary agriculturalists. Since ancient times builders have used local materials to build cities and villages on mountain slopes, dry islets at the bed of a valley, stony plateaus, and sandy seashores. Most localities, from walled cities to tiny hamlets, are still divided into traditional quarters or neighborhoods. Public spaces, especially markets, foster communication among men.

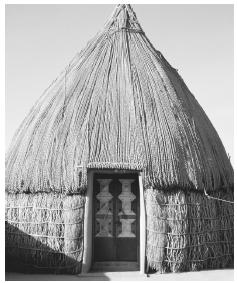

Cultural zones vary in the use of building materials. In villages in northern Tihama timber and straw are used, while in towns shell lime is more common; in southern Tihama timber and brick are used. In the central mountainous region, hewn stone is used; in the highlands, houses are made of stone, burned brick, and stamped clay. In the desert, houses are built from stamped clay and sun-dried mud bricks. These materials also are used in Hadhramaut, whose multistory "skyscrapers" in Shibam are reputed to be the highest mud constructions in the world. Natural stone is used mainly in Mahra and on Socotra.

The majority of buildings originate from pre-Islamic fortified towers that combine in a single structure under a whitewashed flat roof the functions of dwelling, storage, and fortress.

The traditional division of Arab dwellings into men's and women's halves led to the use of separate staircases and room entrances hidden behind partitions. There is a minimum of furniture: cushions and mattresses are placed along the walls for sitting, and special mattresses, which are taken away in the daytime, are used for sleeping. The floor is covered with palm leaf matting, goat-hair rugs, or imported rugs. Cubbyholes are made in thick walls for books, utensils, and clothes.

UNESCO has sponsored international campaigns to protect the architectural heritage, encouraging the use of local materials and building methods. These principles were maintained in the building of the Ministry of Justice in Sana'a and Provincial Health Center and Hospital in Dhamar. The 1990s witnessed a construction boom in the urban centers.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Yemenis usually eat three times a day at home. The traditional diet varies locally and socially and is open to innovations. Generally, there is an early breakfast of sweet strong tea with bread made of sorghum, wheat, or barley; dinner includes a porridge prepared from fenugreek with meat, eggs, vegetables, herbs, and spices, which is served hot in a stone or clay bowl; a light supper consists of vegetables and/or dates. One can drink a glass of tea or a brew of coffee husks outdoors in the daytime. Lentils and peas are traditional staples in addition to sorghum. Many inexpensive restaurants have opened, some of them Lebanese. Local food taboos are those common to the Islamic world: alcohol and pork are officially prohibited.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. At feasts and celebrations, the festive meal of the nomads, roasted or boiled meat from goat or sheep served on heaps of rice, is eaten. In town and villages it is served with side dishes of roasted or fried eggplant and mixed green salads, with fruit or custard with raisins or grapes for dessert. People now consume more fish, poultry, and dairy products. Among the variety of sweets is bint as-sahn, a puff pastry covered with honey. Yemenis prepare special dishes and sweets for nightly breaks during the Ramadan fast. At wedding celebrations and religious feasts, coffee is drunk. In decorated drawingrooms, people smoke water pipes and chew qat.

Basic Economy. About one-fourth of the gross domestic product is derived from agriculture. However, the nation imports more than sixty percent of its food needs. About twenty percent of the population suffers from malnutrition. Agriculture employs more than half the labor force. The principal crops are sorghum, potatoes, dates, wheat, grapes, barley, maize, cotton, millet, and garden vegetables, but only part of the harvest is produced for sale. This is also the case for sheep, goats, and camels. Coffee, biscuits, grapes, sesame seeds, sugar, honey, and dried and salted fish are exported.

Land Tenure and Property. Land can be state, private, or communal. Traditionally, state lands were used for cultivation and public purposes and were controlled by the state authorities; private property consisted of agricultural, building, and other plots; there were Islamic endowments and tribal land was used for grazing livestock and served as areas of tribal responsibility for travelers and protected groups. In the north, customs, laws, and practices concerning land and water allocation are

Groups of chatting men in Sana'a. Public spaces, especially markets, foster communication among men.

based on Islamic, customary, and, after 1962, civil regulations. In the south, the first two practices were supplemented by British law and, after 1967, socialist legislation. After unification, agricultural land was denationalized and returned in the south to those who owned it under the British. About 6 percent of the national territory is arable, 30 percent is occupied by pastures, and 7 percent is forest and woodland.

Commercial Activities. Shops and permanent and weekly markets offer local and imported foodstuffs, qat and frankincense, livestock, manufactured goods, fabrics, and clothing. Goods traditionally associated with the culture, such as side arms, textiles, leather, and agates, also are available for purchase.

Major Industries. The petroleum refinery in Little Aden produces a major share of the industrial output. Other products are foodstuffs, including soft drink bottling and dairy plants; cement and cinder blocks, tiles, and burned bricks; textiles; aluminum utensils, rubber and plastic; and salt. Yemenis still practice traditional handicrafts such as silver and copperwork, dagger manufacturing, carpentry, boat building, pottery, weaving and dyeing, wickerwork, and leather tanning. Electricity is generated from thermal power plants. The major sea ports are Aden, al-Hudayda, al-Mucha, al-Mukalla; international airports are situated in Sana'a, Aden, al-Hudayda, Ta'izz, and al-Mukalla. Economic prospects depend on the development of oil resources.

Trade. The principal exports are livestock and food, cigarettes, leather, and petroleum products, which are shipped mainly to Saudi Arabia, Japan, and Italy. Yemen traditionally exports labor to the Arab world, East Africa, the Indian Ocean area, and the United States. All manner of staples from food to consumer goods are imported.

Division of Labor. Most of the population is employed in agriculture and herding or works as expatriate laborers. Industry (about 5 percent of total labor power), services, construction, and commerce employ for less than half the workforce. There is a labor hierarchy that conforms to the traditional social strata.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. Under law all citizens are equal. The traditional social structure, however, has at the top the Sayyids stratum, descendants of the Prophet Muhammad. The Sayyids competed for the office of Zaydi imam and control sacred enclaves, solved tribal conflicts by mediation, engaged in theology and law, and owned and leased land. Slightly lower on the social scale are the Qadis or Fuqaha (in the south, the Mashayikh ) who perform the same social functions. Qabilis (tribesmen) control their territory and caravan routes, own arable land that most of them cultivate, and carry weapons. The lower strata are underprivileged and have an obscure genealogy. Being under tribal protection, they traditionally were deprived of land ownership and were not allowed to bear arms. The members of this group are called the Bani Khums in the north and the Masakeen and Du'afa (the poor and the weak) in the south. They engage in low-status occupations that in most cases are hereditary, working as smiths, carpenters, potters, brokers, barbers (who also perform circumsion), bloodletters, musicians, heralds, butchers weavers and dyers, and tanners. The Akhdams (servants) wash and bury the dead and clean latrines. The majority of Akhdams and exslaves ( Abeeds ) are of African or Ethiopean descent. All these strata tend to be endogamous or, in the south, observe the marital rule of hypergamy, in which men marry within their strata or lower and women marry their equals or higher-status men. The mass return of expatriates in 1990 has raised the social problem of muwalladin , or Yemenis of mixed origins.

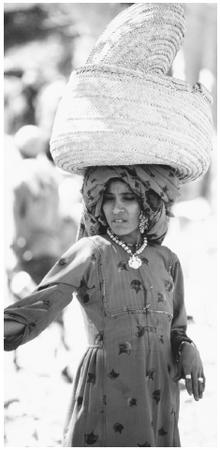

Symbols of Social Stratification. Male Sayyids and Qadis traditionally wore long robes and covered their heads with white or green turbans; their authority also was symbolized by a staff, a ring, and a flag. Tribal symbols include weapons (firearms), dances, greetings, call songs, and tribal poetry. Women's dress reflects not so much class differences but social and regional ones except for the fact that women in nomadic tribes and the most under-privileged strata leave their faces unveiled. In the south, the jambiya is worn only by tribesmen. In the north, men in most social strata carry daggers. Today all Yemeni men prefer to wear jambiyas that are placed vertically at the center of the belt.

Political Life

Government. United Yemen proclaimed itself a presidential republic and a multiparty parliamentary democracy. The parliament consists of the House of Deputies and an appointed Upper Chamber, or Senate. The constitution was approved by referendum in 1991 and was amended in 1994. The president is elected for a five-year term; the last campaign for the presidency was won in 1999 by the general Ali Abdullah Saleh. Executive authority is vested in the prime minister and the cabinet. The

Women have rights guaranteed by law, but gender disparity is widespread.

Supreme Court heads the judicial branch. The press is among the freest in the Arab world.

Leadership and Political Officials. Politics is practiced mostly outside the new democratic institutions. Real power is exercised through a network of personal relations and patronage and clientele ties that involve family, class, and local affinities. Since a multiparty system was not allowed before unification, the strength of party leadership matters today more than does ideology. Among about forty political parties and organizations, the most significant are: the General People's Congress (GPC) of the president, the Yemeni Congregation for Reform (the Islah ) with active Islamic and tribal trends, and the Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP), which, after abortive secession of the south in 1994, has regrouped as a loyal opposition.

Social Problems and Control. In 1991, the court system was set up with the Supreme Court of the Republic at the top in Sana'a, provincial courts of appeal in every governorate, and uniform district courts in the main local centers. In 1994, laws regarding crimes, punishments, and criminal procedures were promulgated; the police and security forces were organized. Those measures were aimed at eradicating corruption, bribery, and favoritism. Other common crimes are larceny in large cities, smuggling along the border, and the taking of hostages in tribal areas; robbery and murder are not widespread. Crime statistics are not representative, since disputes traditionally are solved through mediation, customary tribal arbitration, and mutual accord. Yemenis regard customary justice as less expensive than state courts. Legal practice includes contradictory aspects of secular, religious, and customary regulations.

Military Activity. Military campaigns took place in 1979, 1986, 1987, and 1994. The Defense Forces include an army, a navy, an air force, and paramilitary forces that include the police. Most tribes have their own militias.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

The current development strategies are documented in a five-year plan that calls for a market economy led by the private sector. External assistance, which was withdrawn in the early 1990s, returned after 1994, when the government launched an ambitious economic, financial, and administrative reform program under the auspices of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. In 1996, those sources were joined by the Arab Fund for Social and Economic Development, the Arab Monetary Fund, and the European Union. About an eighth of external aid goes for health and human resources development.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

There are trade unions, professional syndicates, human rights groups, and sport, religious (including charitable), and other informal organizations and associations, most of which have a top-down structure.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. In the cultural stereotype, women are viewed as subordinate and indulgent mothers, sisters, and wives who perform household duties; men are seen as financial providers in the outside world, responsible for the wellbeing and prestige of the family. Long-term male labor migration has resulted in a modification of the traditional division of labor, since women and older children have had to take over some male tasks, particularly in agriculture. Some women in urban centers have jobs in education and health care. Women Islamic activists are very active in the Islah Charitable Society, which helps the poor.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. The 1994 constitution states that women are men's sisters and have rights and duties guaranteed by Islamic Shari'a and secular law. However, gender disparity in all aspects of life outside the family is striking, since religious authorities strongly recommend gender segregation. For example the testimony of two women in court equals that of one man.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Most marriages are arranged by the families: a bridegroom's female relatives suggest potential brides to him and his father, who come to a decision according to the rules of martial conformity. In most cases, the woman's father asks her about her wishes before the marriage contract is prepared. Groom and bride are attached to their respective descent groups through the male line: The father of the groom has to pay a brideprice mahr , and the family of the bride is expected to help her in times of hardship. Arab custom regards as ideal a parallel cousin marriage in which the father's brother's daughter is the bride as well as other endogamous marriages. Shari'a law allows a man to marry up to four wives if he treats them all as equals; the rate of polygamy is low. Half of the adult population is married, four percent is widowed, and one percent is divorced. Both men and women can request a divorce. If it was initiated by the husband, the ex-wife keeps her brideprice and can remarry after four months and ten days, during which time the ex-husband has to support her. Children up to seven years of age remain with

A traditional Yemeni hut in the village of Tihamah uses timber and straw.

the mother if she does not remarry. Divorce and remarriage are not stigmatized.

Domestic Unit. The most common type family, especially outside urban centers, is patrilocal and extended. There are also nuclear families, as well as fraternal joint families (households consisting of the nuclear families of two or more brothers). The average household has 6.7 persons. Most of the household economy is controlled by men. In villages, men are responsible for qat and cultivation of the crops, whereas women grow vegetables and take care of domestic animals.

Inheritance. Inheritance customs stress the right of primogeniture, which gives preference to the oldest brother. In accordance with Shari'a law, after a husband's death, his mother inherits one-sixth of his estate and one-eighth goes to his widow; a woman inherits half of her brother's share. If she has no brothers or sisters, she gets half the property. Formally inherited property, including land, is at a woman's disposal, but often it is managed by her male relatives.

Kin Groups. This stratified society is based on the tribal idiom of common descent, which serves as the source of mutual rights and obligations within each group. This flexible structure has several levels above the nuclear family: a unit of patrilineal kin ( bayt ), whose members share a house or closely interact in other ways; the larger descent group, the clan or subtribe ( fakhdh ); a tribe ( qabila ); and a tribal confederation ( silf ). Individuals usually identify themselves with the lowest or highest levels of kinship, since alliances are not determined solely by kin principles.

Socialization

Infant Care. Children are culturally, socially, and religiously valued, although infant mortality is high. Mothers are responsible for the care of young children, and older daughters take an active part in raising their siblings. Only male children give their mother high status. Small children usually are carried by their caretakers. Girls and small children sleep in the women's half of the house, while adolescent boys sleep apart. Children rarely are punished. If they fight, they are separated by adults.

Child Rearing and Education. Most women give birth at home. A son's birth involves a circumcision festivity during which the mother gets presents. Circumcision (clitoridectomy) of newly born female children usually is done without a special ceremony. Babies are swaddled, and children are regarded as incapable of self-control until age four. Male children are believed to be particularly vulnerable to the evil eye. More emphasis is placed on the education of sons than on that of daughters in free public, or private as well as religious schools, all of which are sexually segregated.

Higher Education. Gender segregation is practiced in higher education, which has been developing rapidly since unification. In addition to national universities in Sana'a and Aden, state and private universities are being organized in al-Mukalla, Taiz, Ibb, Dhammar, and al-Hudayda.

Etiquette

Social and individual interactions are determined by customary law and religious regulations, which include structured series of verbal exchanges and salutations in greeting or saying good-bye and the avoidance of women who are not close relatives. The strata disparity reflected in behavioral norms has been lessening but still exists in regard to marital and other rules. Cultural values include hospitality, respect for elders, decency, and good manners while eating from a communal dish. Guests do not accept more than three cups of coffee or tea and

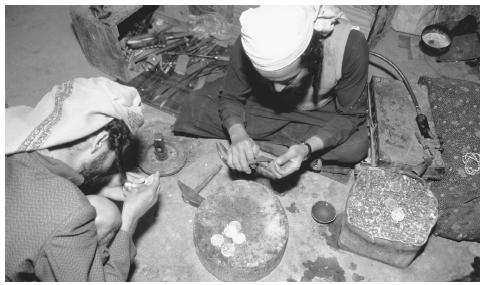

Two Jewish jewelers at work in north Sana'a. Goods produced by small vendors are an important part of market-based commercial activity.

wobble the cup from side to side to show that nothing more is required, and shoes are left outdoors before one enters a dwelling. Physical distance between social interactors is close. The spatial disposition of social interactors is circular at tribal meetings and linear during ritual ceremonies in mosques and outdoors; indoors, it is at the perimeter, with the best position at the far corner of the wall in which the door is situated. In a market one is expected to enjoy the process of bargaining. During social events, poets, singers, and dancers may transgress the precepts of acceptable behavior.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Sunni Islam of the Shafi'i school dominates in the south and many regions of the north; the Zaydi Shi'a school with its center in Sa'da is practiced mainly among the tribes of central mountains and the adjacent highlands. A much smaller Islamic group near Manakha is the Isma'ilis, who are divided into the Sulaymani ( Makarima ) branch, which is connected with Najaran, and the Dawudi ( Boharas ) which is linked with India.

Religious Practitioners. Islamic scholars, judges, managers of charitable property, elders in sacred enclaves, and leaders of communal prayer used to be recruited primarily from the two upper strata but now may belong to other classes as well.

Rituals and Holy Places. Yemenis observe the Five Pillars of Islam, including five prayers a day and a daytime fast during the month of Ramadan. The weekly day of rest is Friday. Religious celebrations include 27 Ramadan, the Night of Power; 1 Shawwal, the Lesser Feast; 10 Dhu al-Hijja, the Greater Feast, or the Feast of Sacrifice, commemorating the end of the pilgrimage to Mecca; 12 Rabi' al-Awwal, the birthday of the Prophet; 10 Muharram, the day of the martyrdom of Imam Husayn; and 27 Rajab, the day of the Prophet's miraculous journey. In mid-Rajab, pilgrimages are usually made to the tombs of local saints.

Death and the Afterlife. The body of the deceased is washed, perfumed, and wrapped in a white, unseamed shroud. The deceased has to be buried before sunset on the day of death. Women do not accompany the body to the grave, staying outside the cemetery. During the first three days of mourning, the Koran is read and relatives and friends visit the family of the dead person. Remembrance sessions usually are held on the seventh and fortieth days after death.

Medicine and Health Care

The Sayyids and Qadis/Mashayikh are reputed to be effective in giving verbal therapy; some are said to heal illnesses by placing their hands over or breathing on a patient. Tribesmen are known as healers of wounds and snake bites, barbers specialize in blood letting, and both use cauterization, preventive diets and herbal treatments. Traditionally, disease is seen as the effect of bad winds and an imbalance of the four humors of the body. Modern health programs have been established.

Secular Celebrations

National Day on 22 May commemorates the country's unification. The Revolution of 26 September 1962 in the north and the beginning of revolt in the south on 14 October 1963 also are celebrated.

The Arts and Humanities

Literature. Medieval culture was rich in historical, geographic, and religious works; agricultural almanacs; astronomical treatises; and rhymed prose. Poetry in classical and colloquial styles is the most popular art form. Since the Middle Ages, poetry has been spoken, sung, and improvised during social events, at performances, and in competitions.

Graphic Arts. Rich traditions of decorative art, such as silver jewelry, embroidered garments, handwoven textiles, and architectural decor, are still practiced. There are art galleries in large cities with modern drawings, paintings, and sculptures.

Performance Arts. Traditional performaces include musical-poetical improvisations called dan in the Hadhramaut, at which singers chant a tune without words and poets offer them a freshly created text line by line. There are choral ritual processions, tribal call songs, special types of regional songs, and local and strata dances.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

The General Organization for Antiquities, Museums, and Manuscripts (GOAMM), with the help of the main universities, does archaeological, historical, and ethnographic studies. GOAMM also coordinates research run by the American Institute for Yemeni Studies, the German Archaeological Institute, the French Center for Yemeni Studies, the British-Yemeni Society, and Russian scientific expeditions. These institutions study social activities, methods of administration, urbanization, land tenure practices, and other aspects of the social and political sciences. Physical sciences and applications, as well as vocational and technical education, require further development.

Bibliography

Adib, Naziha, Ferdous al-Mukhtar, et al. Arabic Cuisine from the Gulf to the Mediterranean , 1993.

Adra, Najwa. "Qabyala: The Tribal Concept in the Central Highlands of the Yemen Republic." Ph.D dissertation, Philadelphia: Temple University, 1982.

Al-Amri, Husayn. Yemen in the 18th and 19th Centuries , 1985.

Almadhagi, Ahmed Noman. Yemen and the United States: A Study of a Small Power and a Super State Relationship, 1962–1994 , 1996.

Al-Sabban, Abd al-Q Muhammad. Visits and Customs: The Visit to the Tomb of the Prophet Hud , translated by Linda Boxberger and Awad Abu Hulayqa, 1998.

Auchterlonie, Paul. Yemen , rev. ed., 1998.

Bidwell, Robin. Travellers in Arabia , 1994.

Buchman, Davie. "The Underground Friends of God and Their Adversaries: A Case Study and Survey of Sufism in Contemporary Yemen." Yemen Update (Bulletin of the American Institute for Yemeni Studies) 39:21–24.

Buringa, Joke (ed. By Marta Colburn). Bibliography on Women in Yemen , 1992.

Burrowes, Robert D. Historical Dictionary of Yemen , 1995.

Carapico, Sheila. Civil Society in Yemen. The Political Economy of Activism in Modern Arabia, 1998.

Caton, Steven C. "Peaks of Yemen I Summon": Poetry as Cultural Practice in a North Yemeni Tribe , 1990.

Costa, Paolo M. Studies in Arabian Architecture , 1995.

Crociani, Paola. Portrets of Yemen , 1996.

Damluji, Salma Samar. The Valley of Mud Brick Architecture , 1992.

Daum, Werner, ed. Yemen: 3000 Years of Art and Civilisation in Arabia Felix , 1987.

Doe, Brian. Socotra, Island of Tranquility , 1992.

Dostal, Walter. Ethnographica Jemenica , 1992.

Dresh, Paul K. Tribes, Government, and History in Yemen , 1989.

Eickelman, Dale F. The Middle East: An Anthropological Approach , 1981.

Elgood, Robert. The Arms and Armour of Arabia in the 18th–19th, and 20th Centuries , 1994.

Freitag, Ulrike, and William G. Clarence-Smith, eds. Hadhrami Traders, Scholars and Statesmen in the Indian Ocean, 1750s–1960s , 1997.

Gerholm, Tomas. Market, Mosque, and Mafraj: Social Inequality in a Yemeni Town , 1977.

Gingrich, Andre, et al., eds. Studies in Oriental Culture and History: Festschrift for Walter Dostal , 1993.

—— and Johann Heiss. Beitrage zur Ethnographie der Provinz Sa'da (Nordjemen) , 1986.

Glaser, Eduard. My Journey through Arhab and Hashid , translated by David Warburton, 1993.

Halliday, Fred. Arabs in Exile: Yemen Migrants in Urban Britain , 1992.

Hubaishi, Husain. Legal System and Basic Law in Yemen , 1988.

Ingrams, Doreen. A Time in Arabia , 1970.

Ingrams, Harold. Arabia and the Isles , 1966.

Knysh, Alexandr. "The Cult of Saints in Hadramawt: An Overview." New Arabian Studies , 1:37–152, 1993.

——. "The Cult of Saints and Islamic Reformism in Early Twentieth Century Hadramawt." New Arabian Studies 4: 139–167, 1997.

Korotayev, Andrey. Pre-Islamic Yemen: Socio-Political Organisation of the Sabaean Cultural Area in the 2nd and 3rd Centuries AD , 1996.

Kostiner, Joseph. Yemen. The Torturous Quest for Unity 1990–1994 , 1996.

Lewis, Herbert. After the Eagles Landed: The Yemenites of Israel , 1994.

Makhlouf, Carla. Changing Veils: Women and Modernisation in North Yemen , 1979.

Messick, Brinkley M. The Calligraphic State: Textual Domination and History in a Muslim Society , 1993.

Muchawsky-Schnapper, Ester. The Jews of Yemen: Highlights of the Israel Museum Collections , 1994.

Myntti, Cynthia. Women in Rural Yemen , 1978.

——. "Notes on Mystical Healers in the Higariyya." Arabian Studies 8: 171–176, 1990.

Naumkin, Vitaly. Island of the Phoenix: An Ethnographic Study of the People of Socotra , 1993.

Phillips, Carl. "Archaeological Research in Yemen." The British-Yemeni Society Journal 4: 22–28, 1996.

Pieragostini, Karl. Britain, Aden and South Arabia: Abandoning Empire , 1991.

Posey, Sarah. Yemeni Pottery: The Littlewood Collection , 1994.

Pridham, Brian, ed. Contemporary Yemen: Politics and Historical Background , 1984.

Qafisheh, Hamdi A. Yemeni Arabic Reference Grammar , 1992.

Rodionov, Mikhair. "Field Data on Folk Medicine from the Hadramawt." Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 26: 125–133, 1996.

——. "Poetry and Power in Hadramawt. New Arabian Studies 3: 118–133, 1996.

—— and Mikhail Suvorov, eds. Cultural Anthropology of Southern Arabia: Hadramawt Revisited , 1999.

Sedov, Alexandr, and Ahmad BaTayi. "Temples of Ancient Hadramawt." Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 24: 183–196, 1994.

Serjeant, Robert B. Prose and Poetry from Hadramawt: South Arabian Poetry, I , 1951.

——. Society and Trade in South Arabia , 1996.

—— and Ronal Lewcock, eds. San'a' , 1983.

Stevenson, Thomas B. Social Change in a Yemeni Highlands Town , 1985.

——. Studies on Yemen, 1975–1900: A Bibliography of European-Language Sources for Social Scientists , 1994.

——. "Yemen Filmography." Yemen Update (Bulletin of the American Institute for Yemeni Studies) 40: 29–31, 1998.

al-Suwaydi, Jamal, ed. The Yemeni War of 1994. Causes and Consequences, 1995.

Tobi, Jacob. West of Aden: A Survey of the Aden Jewish Community , 1994.

UNICEF. Thee Situation of Women and Children in the Republic of Yemen 1992 , 1993.

Varisco, Daniel M. "The Adaptive Dynamics of Water Allocation in al-Ahjur, Yemen Arab Republic." Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 1982.

——. Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan , 1994.

Watson, Jannet C. E. A Syntax of San'ani Arabic , 1993.

Weir, Shelagh. Oat in Yemen: Consumption and Social Change , 1985.

Wenner, Manfred W. Modern Yemen, 1918–1966 , 1967.