Culture of Wales

Culture Name

Welsh

Alternative Name

Cymru, the nation; Cymry, the people; Cymraeg, the language

Orientation

Identification. The Britons, a Celtic tribe, who first settled in the area that is now Wales, had already begun to identify themselves as a distinct culture by the sixth century C.E. The word "Cymry," referring to the country, first appeared in a poem dating from 633. By 700 C.E. , the Britons referred to themselves as Cymry, the country as Cymru, and the language as Cymraeg. The words "Wales" and "Welsh" are Saxon in origin and were used by the invading Germanic tribe to denote people who spoke a different language. The Welsh sense of identity has endured despite invasions, absorption into Great Britain, mass immigration, and, more recently, the arrival of non-Welsh residents.

Language has played a significant role in contributing to the sense of unity felt by the Welsh; more than the other Celtic languages, Welsh has maintained a significant number of speakers. During the eighteenth century a literary and cultural rebirth of the language occurred which further helped to solidify national identity and create ethnic pride among the Welsh. Central to Welsh culture is the centuries-old folk tradition of poetry and music which has helped keep the Welsh language alive. Welsh intellectuals in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries wrote extensively on the subject of Welsh culture, promoting the language as the key to preserving national identity. Welsh literature, poetry, and music flourished in the nineteenth century as literacy rates and the availability of printed material increased. Tales that had traditionally been handed down orally were recorded, both in Welsh and English, and a new generation of Welsh writers emerged.

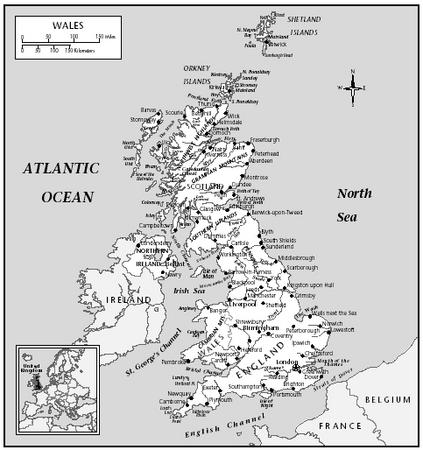

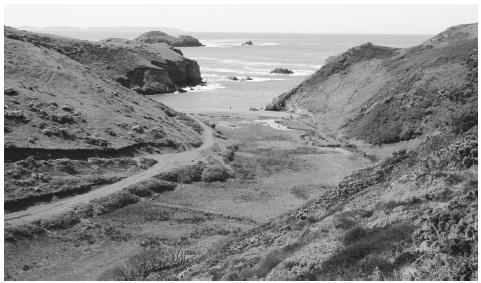

Location and Geography. Wales is a part of the United Kingdom and is located in a wide peninsula in the western portion of the island of Great Britain. The island of Anglesey is also considered a part of Wales and is separated from the mainland by the Menai Strait. Wales is surrounded by water on three sides: to the north, the Irish Sea; to the south, the Bristol Channel; and to the west, Saint George's Channel and Cardigan Bay. The English counties of Cheshire, Shropshire, Hereford, Worcester, and Gloucestershire border Wales on the east. Wales covers an area of 8,020 square miles (20,760 square kilometers) and extends 137 miles (220 kilometers) from its most distant points and varies between 36 and 96 miles (58 and 154 kilometers) in width. The capital, Cardiff, is located in the southeast on the Severn Estuary and is also the most important seaport and shipbuilding center. Wales is very mountainous and has a rocky, irregular coastline with numerous bays, the largest of which is Cardigan Bay to the west. The Cambrian Mountains, the most significant range, run north-south through central Wales. Other mountain ranges include the Brecon Beacons to the southeast and Snowdon in the northwest, which reaches an elevation of 3,560 feet (1,085 meters) and is the highest mountain in Wales and England. The Dee River, with its headwaters in Bala Lake, the largest natural lake in Wales, flows through northern Wales into England. Numerous smaller rivers cover the south, including the Usk, Wye, Teifi, and Towy.

The temperate climate, mild and moist, has ensured the development of an abundance of plant and animal life. Ferns, mosses, and grasslands as well as numerous wooded areas cover Wales. Oak, mountain ash, and coniferous trees are found in mountainous regions under 1,000 feet (300 meters). The pine marten, a small animal similar to a mink, and the polecat, a member of the weasel family, are

Wales

found only in Wales and nowhere else in Great Britain.

Demography. The latest surveys place the population of Wales at 2,921,000 with a density of approximately 364 people per square mile (141 per square kilometers). Almost three-quarters of the Welsh population reside in the mining centers of the south. The popularity of Wales as a vacation destination and weekend retreat, especially near the border with England, has created a new, nonpermanent population.

Linguistic Affiliation. There are approximately 500,000 Welsh speakers today and, due to a renewed interest in the language and culture, this number may increase. Most people in Wales, however, are English-speaking, with Welsh as a second language; in the north and west, many people are Welsh and English bilinguals. English is still the main language of everyday use with both Welsh and English appearing on signs. In some areas, Welsh is used exclusively and the number of Welsh publications is increasing.

Welsh, or Cymraeg, is a Celtic language belonging to the Brythonic group consisting of Breton, Welsh, and the extinct Cornish. Western Celtic tribes first settled in the area during the Iron Age, bringing with them their language which survived both Roman and Anglo-Saxon occupation and influence, although some features of Latin were introduced into the language and have survived in modern Welsh. Welsh epic poetry can be traced back to the sixth century C.E. and represents one of the oldest literary traditions in Europe. The poems of Taliesin and Aneirin dating from the late seventh century C.E. reflect a literary and cultural awareness from an early point in Welsh history. Although there were many factors affecting the Welsh language, especially contact with other language groups, the Industrial Revolution of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries marked a dramatic decline in the number of Welsh speakers, as many non-Welsh people, attracted by the industry that had developed around coal mining in the south and east, moved into the area. At the same time, many Welsh people from rural areas left to find work in London or abroad. This large-scale migration of non-Welsh-speaking workers greatly accelerated the disappearance of Welsh-speaking communities. Even though there were still around forty Welsh-language publications in the mid-nineteenth century, the regular use of Welsh by the majority of the population began to drop. Over time two linguistic groups emerged in Wales; the Welsh-speaking region known as the Y Fro Cymraeg to the north and west, where more than 80 percent of the population speaks Welsh, and the Anglo-Welsh area to the south and east where the number of Welsh speakers is below 10 percent and English is the majority language. Up until 1900, however, almost half the population still spoke Welsh.

In 1967 the Welsh Language Act was passed, recognizing the status of Welsh as an official language. In 1988 the Welsh Language Board was established, helping to ensure the rebirth of Welsh. Throughout Wales there was a serious effort in the second half of the twentieth century to maintain and promote the language. Other efforts to support the language included Welsh-language television programs, bilingual Welsh-English schools, as well

A procession heading to the National Eisteddfod Festival in Llandudno, Wales.

as exclusively Welsh-language nursery schools, and Welsh language courses for adults.

Symbolism. The symbol of Wales, which also appears on the flag, is a red dragon. Supposedly brought to the colony of Britain by the Romans, the dragon was a popular symbol in the ancient world and was used by the Romans, the Saxons, and the Parthians. It became the national symbol of Wales when Henry VII, who became king in 1485 and had used it as his battle flag during the battle of Bosworth Field, decreed that the red dragon should become the official flag of Wales. The leek and the daffodil are also important Welsh symbols. One legend connects the leek to Saint David, the patron saint of Wales, who defeated the pagan Saxons in a victorious battle that supposedly occurred in a field of leeks. It is more likely that leeks were adopted as a national symbol because of their importance to the Welsh diet, particularly during Lent when meat was not allowed. Another, less famous Welsh symbol consists of three ostrich plumes and the motto "Ich Dien" (translation: "I serve") from the Battle of Crecy, France, in 1346. It was probably borrowed from the motto of the King of Bohemia, who led the cavalry charge against the English.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. The earliest evidence of a human presence in Wales dates from the Paleolithic, or Old Stone Age, period almost 200,000 years ago. It was not until the Neolithic and Bronze Age period around 3,000 B.C.E. , however, that a sedentary civilization began to develop. The first tribes to settle in Wales, who probably came from the western coastal areas of the Mediterranean, were people generally referred to as the Iberians. Later migrations from northern and eastern Europe brought the Brythonic Celts and Nordic tribes to the area. At the time of the Roman invasion in 55 B.C.E. , the area was made up of the Iberian and Celtic tribes who referred to themselves as Cymry. The Cymry tribes were eventually subjugated by the Romans in the first century C.E. Anglo-Saxon tribes also settled in Britain during this period, pushing other Celtic tribes into the Welsh mountains where they eventually united with the Cymry already living there. In the first centuries C.E. , Wales was divided into tribal kingdoms, the most important of which were Gwynedd, Gwent, Dyved, and Powys. All of the Welsh kingdoms later united against the Anglo-Saxon invaders, marking the beginning of an official division between England and Wales. This boundary became official with the construction of Offa's Dyke around the middle of the eighth century C.E. Offa's Dyke was at first a ditch constructed by Offa, the king of Mercia, in an attempt to give his territories a well-defined border to the west. The Dyke was later enlarged and fortified, becoming one of the largest human-made boundaries in Europe and covering 150 miles from the northeast coast to the southeast coast of Wales. It remains to this day the line that divides English and Welsh cultures.

When William the Conqueror (William I) and his Norman army conquered England in 1066, the three English earldoms of Chester, Shrewsbury, and Hereford were established on the border with Wales. These areas were used as strong points in attacks against the Welsh and as strategic political centers. Nevertheless, the only Welsh kingdom to fall under Norman control during the reign of William I (1066–1087) was Gwent, in the southeast. By 1100 the Norman lords had expanded their control to include the Welsh areas of Cardigan, Pembroke, Brecon, and Glamorgan. This expansion into Welsh territory led to the establishment of the March of Wales, an area previously ruled by the Welsh kings.

The Welsh continued to fight Norman and Anglo-Saxon control in the first part of the twelfth century. By the last half of the twelfth century the three Welsh kingdoms of Gwynedd, Powys, and Deheubarth were firmly established, providing a permanent base for Welsh statehood. The principal settlements of Aberffraw in Gwynedd, Mathrafal in Powys, and Dinefwr in Deheubarth formed the core of Welsh political and cultural life. Although the Welsh kings were allies, each ruled separate territories swearing loyalty to the king of England. The establishment of the kingdoms marked the beginning of a period of stability and growth. Agriculture flourished, as did scholarship and the Welsh literary tradition. A period of unrest and contested succession followed the deaths of the three Welsh kings as different factions fought for control. The stability provided by the first kings was never restored in Powys and Deheubarth. The kingdom of Gwynedd was successfully united once again under the reign of Llywelyn ap Iorwerth (d. 1240) following a brief power struggle. Viewing Llywelyn as a threat, King John (1167–1216) led a campaign against him which led to Llywelyn's humiliating defeat in 1211. Llywelyn, however, turned this to his advantage and secured the allegiance of other Welsh leaders who feared total subjugation under King John. Llywelyn became the leader of the Welsh forces and, although conflict with King John continued, he successfully united the Welsh politically and eventually minimized the king of England's involvement in Welsh affairs. Dafydd ap Llywelyn, Llywelyn ap Iorwerth's son and heir, attempted to broaden Welsh power before his premature death in 1246. With Dafydd leaving no heirs, succession to the Welsh throne was contested by Dafydd's nephews and in a series of battles between 1255 and 1258 Llwelyn ap Gruffydd (d. 1282), one of the nephews, assumed control of the Welsh throne, crowning himself Prince of Wales. Henry III officially recognized his authority over Wales in 1267 with the Treaty of Montgomery and in turn Llwelyn swore allegiance to the English crown.

Llwelyn succeeded in firmly establishing the Principality of Wales, which consisted of the twelfth century kingdoms of Gwynedd, Powys, and Deheubarth as well as some parts of the March. This period of peace, however, did not last long. Conflict arose between Edward I, who succeeded Henry III, and Llwelyn, culminating in an English invasion of Wales in 1276, followed by war. Llwelyn was forced into a humiliating surrender that included relinquishing control over the eastern part of his territory and an acknowledgment of fealty paid to Edward I annually. In 1282 Llwelyn, aided this time by the Welsh nobility of other regions, rebelled against Edward I only to be killed in combat. The Welsh forces continued to fight but finally capitulated to Edward I in the summer of 1283, marking the beginning of a period of occupation by the English.

Although the Welsh were forced to surrender, the struggle for unity and independence over the previous one hundred years had been crucial in shaping Welsh politics and identity. During the fourteenth century economic and social difficulties prevailed in Wales. Edward I embarked on a program of castle building, both for defensive purposes and to shelter English colonists, which was continued by his heir Edward II. The result of his efforts can still be seen in Wales today, which has more castles per square mile than any other area of Europe.

At the end of the 1300s Henry IV seized the throne from Richard II, provoking a revolt in Wales where support for Richard II was strong. Under the leadership of Owain Glyndwr, Wales united to rebel against the English king. From 1400 to 1407 Wales once again asserted its independence from England. England did not regain control of Wales again until 1416 and the death of Glyndwr, marking the last Welsh uprising. The Welsh submitted to Henry VII (1457–1509), the first king of the house of Tudor, whom they regarded as a countryman. In 1536 Henry VIII declared the Act of Union, incorporating Wales into the English realm. For the first time in its history Wales obtained uniformity in the administration of law and justice, the same political rights as the English, and English common law in the courts. Wales also secured parliamentary representation. Welsh landowners exercised their authority locally, in the name of the king, who granted them their land and property. Wales, although no longer an independent nation, had finally obtained unity, stability, and, most importantly, statehood and recognition as a distinct culture.

National Identity. The different ethnic groups and tribes that settled in ancient Wales gradually merged, politically and culturally, to defend their territory from first, the Romans, and later the Anglo-Saxon and Norman invaders. The sense of national identity was formed over centuries as the people of Wales struggled against being absorbed into neighboring cultures. The heritage of a common Celtic origin was a key factor in shaping Welsh identity and uniting the warring kingdoms. Cut off from other Celtic cultures to the north in Britain and in Ireland, the Welsh tribes united against their non-Celtic enemies. The development and continued use of the Welsh language also played important roles in maintaining and strengthening the national identity. The tradition of handing down poetry and stories orally and the importance of music in daily

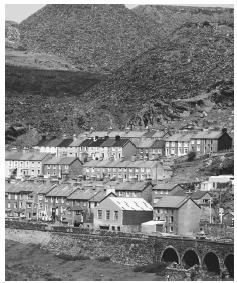

A pile of slate rests above a Welsh town. Mining is an important industry in Wales.

life were essential to the culture's survival. With the arrival of book publishing and an increase in literacy, the Welsh language and culture were able to continue to flourish, through the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century, despite dramatic industrial and social changes in Great Britain. A revival of Welsh nationalism in the second half of the twentieth century once again brought to the forefront the concept of a unique Welsh identity.

Ethnic Relations. With the Act of Union, Wales gained peaceful relations with the English while maintaining their ethnic identity. Until the late eighteenth century Wales was predominantly rural with most of the population living in or near small farming villages; contact with other ethnic groups was minimal. The Welsh gentry, on the other hand, mixed socially and politically with the English and Scottish gentry, producing a very Anglicized upper class. The industry that grew up around coal mining and steel manufacturing attracted immigrants, principally from Ireland and England, to Wales starting in the late eighteenth century. Poor living and working conditions, combined with the arrival of large numbers of immigrants, caused social unrest and frequently led to conflicts—often violent in nature—among different ethnic groups. The decline of heavy industry in the late nineteenth century, however, caused an outward migration of Welsh and the country ceased to attract immigrants. The end of the twentieth century brought renewed industrialization and with it, once again, immigrants from all over the world, although without notable conflicts. The increased standard of living throughout Great Britain has also made Wales a popular vacation and weekend retreat, principally for people from large urban areas in England. This trend is causing significant tension, especially in Welsh-speaking and rural areas, among residents who feel that their way of life is being threatened.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

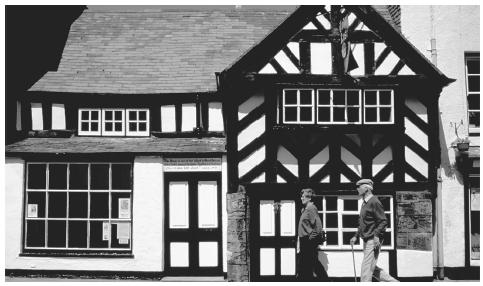

The development of Welsh cities and towns did not begin until industrialization in the late 1700s. Rural areas are characterized by a scattering of isolated farms, typically consisting of the older, traditional whitewashed or stone buildings, usually with slate roofs. Villages evolved from the early settlements of the Celtic tribes who chose particular locations for their agricultural or defensive value. More successful settlements grew and became the political and economic centers, first of the kingdoms, then later the individual regions, in Wales. The Anglo-Norman manorial tradition of buildings clustered on a landowner's property, similar to rural villages in England, was introduced to Wales after the conquest of 1282. The village as a center of rural society, however, became significant only in southern and eastern Wales; other rural areas maintained scattered and more isolated building patterns. Timber-framed houses, originally constructed around a great hall, emerged in the Middle Ages in the north and east, and later throughout Wales. In the late sixteenth century, houses began to vary more in size and refinement, reflecting the growth of a middle class and increasing disparities in wealth. In Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, landowners built brick houses that reflected the vernacular style popular in England at the time as well as their social status. This imitation of English architecture set landowners apart from the rest of Welsh society. After the Norman conquest, urban development began to grow around castles and military camps. The bastide, or castle town, although not large, is still significant to political and administrative life. Industrialization in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries caused an explosion of urban growth in the southeast and in Cardiff. Housing shortages were common and several families, often unrelated, shared dwellings. Economic affluence and a population increase created a demand for new construction in the late twentieth century. Slightly over 70 percent of homes in Wales are owner-occupied.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. The importance of agriculture to the Welsh economy as well as the availability of local products has created high food standards and a national diet that is based on fresh, natural food. In coastal areas fishing and seafood are important to both the economy and the local cuisine. The type of food available in Wales is similar to that found in the rest of the United Kingdom and includes a variety of food from other cultures and nations.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Special traditional Welsh dishes include laverbread, a seaweed dish; cawl, a rich broth; bara brith, a traditional cake; and pice ar y maen, Welsh cakes. Traditional dishes are served at special occasions and holidays. Local markets and fairs usually offer regional products and baked goods. Wales is particularly known for its cheeses and meats. Welsh rabbit, also called Welsh rarebit, a dish of melted cheese mixed with ale, beer, milk, and spices served over toast, has been popular since the early eighteenth century.

Basic Economy. Mining, especially of coal, has been the chief economic activity of Wales since the seventeenth century and is still very important to the economy and one of the leading sources of employment. The largest coalfields are in the southeast and today produce about 10 percent of Great Britain's total coal production. Iron, steel, limestone, and slate production are also important industries. Although heavy industry has played a significant role in the Welsh economy and greatly affected Welsh society in the nineteenth century, the country remains largely agricultural with almost 80 percent of the land used for agricultural activities. The raising of livestock, particularly cattle and sheep, is more important than crop farming. The principal crops are barley, oats, potatoes, and hay. Fishing, centered on the Bristol Channel, is another important commercial activity. The economy is integrated with the rest of Great Britain and as such Wales is no longer exclusively dependent on its own production. Although agriculture accounts for much of the economy, only a small segment of the total population actually works in this area and agricultural output is largely destined for sale. Many foreign companies that produce consumer goods, particularly Japanese firms, have opened factories and offices in Wales in recent years, providing employment and encouraging economic growth.

Land Tenure and Property. In ancient Wales land was informally controlled by tribes who fiercely protected their territory. With the rise of the Welsh kingdoms, land ownership was controlled by the kings who granted their subjects tenure. Because of the scattered and relatively small population of Wales, however, most people lived on isolated farms or in small villages. After the Act of Union with England, the king granted land to the nobility and later, with the rise of a middle class, the Welsh gentry had the economic power to purchase small tracts of land. Most Welsh people were peasant farmers who either worked the land for landowners or were tenant farmers, renting small patches of land. The advent of the industrial revolution caused a radical change in the economy and farmworkers left the countryside in large numbers to seek work in urban areas and coal mines. Industrial workers rented living quarters or, sometimes, were provided with factory housing.

Today, land ownership is more evenly distributed throughout the population although there are still large privately owned tracts of land. A new awareness of environmental issues has led to the creation of national parks and protected wildlife zones. The Welsh Forestry Commission has acquired land formerly used for pasture and farming and initiated a program of reforestation.

Major Industries. Heavy industry, such as mining and other activities associated with the port of Cardiff, once the busiest industrial port in the world, declined in the last part of the twentieth century. The Welsh Office and Welsh Development Agency have worked to attract multinational companies to Wales in an effort to restructure the nation's economy. Unemployment, higher on average in the rest of the United Kingdom, is still a concern. Industrial growth in the late twentieth century was concentrated mostly in the area of science and technology. The Royal Mint was relocated to Llantrisant, Wales in 1968, helping create a banking and financial services industry. Manufacturing is still the largest Welsh industry, with financial services in second place, followed by education, health and social services, and wholesale and retail trade. Mining accounts for only 1 percent of the gross domestic product.

Trade. Integrated with the economy of the United Kingdom, Wales has important trade relations with other regions in Britain and with Europe. Agricultural products, electronic equipment, synthetic fibers, pharmaceuticals, and automotive parts are the principal exports. The most important heavy industry is the refining of imported metal ore to produce tin and aluminum sheets.

Political Life

Government. The Principality of Wales is governed from Whitehall in London, the name of the administrative and political seat of the British government. Increasing pressure from Welsh leaders for more autonomy brought devolution of administration in May 1999, meaning that more political power has been given to the Welsh Office in Cardiff. The position of secretary of state for Wales, a part of the British prime minister's cabinet, was created in 1964. In a 1979 referendum a proposal for the creation of a nonlegislating Welsh Assembly was rejected but in 1997 another referendum passed by a slim margin, leading to the 1998 creation of the National Assembly for Wales. The assembly has sixty members and is responsible for setting policy and creating legislation in areas regarding education, health, agriculture, transportation, and social services. A general reorganization of government throughout the United Kingdom in 1974 included a simplification of Welsh administration with smaller districts regrouped to form larger constituencies for economic and political reasons. Wales was reorganized into eight new counties, from thirteen originally, and within the counties thirty-seven new districts were created.

Leadership and Political Officials. Wales has always had strong left wing and radical political parties and leaders. There is also a strong political awareness throughout Wales and voter turnout at elections is higher on average than in the United Kingdom as a whole. In most of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the Liberal Party dominated Welsh politics with the industrial regions supporting the Socialists. In 1925 the Welsh Nationalist Party, known as Plaid Cymru, was founded with the intention of gaining independence for Wales as a region within the European Economic Community. Between World Wars I and II severe economic depression caused almost 430,000 Welsh to immigrate and a new political activism was born with an emphasis on social and economic reform. After World War II the Labor Party gained a majority of support. During the late 1960s Plaid Cymru and the Conservative Party won seats in parliamentary elections, weakening the Labor Party's traditional

The Pembrokeshire landscape in Cribyn Walk, Solva, Dyfed. Wales is surrounded by water on three sides.

dominance of Welsh politics. In the 1970s and 1980s Conservatives gained even more control, a trend that was reversed in the 1990s with the return of Labor dominance and the increased support for Plaid Cymru and Welsh nationalism. The Welsh separatist, nationalist movement also includes more extremist groups who seek the creation of a politically independent nation on the basis of cultural and linguistic differences. The Welsh Language Society is one of the more visible of these groups and has stated its willingness to use civil disobedience to further its goals.

Military Activity. Wales does not have an independent military and its defense falls under the authority of the military of the United Kingdom as a whole. There are, however, three army regiments, the Welsh Guards, the Royal Regiment of Wales, and the Royal Welch Fusiliers, that have historical associations with the country.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

Health and social services fall under the administration and responsibility of the secretary of state for Wales. The Welsh Office, which works with the county and district authorities, plans and executes matters relating to housing, health, education, and welfare. Terrible working and living conditions in the nineteenth century brought significant changes and new policies regarding social welfare that continued to be improved upon throughout the twentieth century. Issues regarding health care, housing, education, and working conditions, combined with a high level of political activism, have created an awareness of and demand for social change programs in Wales.

Gender Roles and Statuses

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Historically, women had few rights, although many worked outside the home, and were expected to fulfill the role of wife, mother, and, in the case of unmarried women, caregiver to an extended family. In agricultural areas women worked alongside male family members. When the Welsh economy began to become more industrialized, many women found work in factories that hired an exclusively female workforce for jobs not requiring physical strength. Women and children worked in mines, putting in fourteen-hour days under extremely harsh conditions. Legislation was passed in the mid-nineteenth century limiting the working hours for women and children but it was not until the beginning of the twentieth century that Welsh women began to demand more civil rights. The Women's Institute, which now has chapters throughout the United Kingdom, was founded in Wales, although all of its activities are conducted in English. In the 1960s another organization, similar to the Women's Institute but exclusively Welsh in its goals, was founded. Known as the Merched y Wawr, or Women of the Dawn, it is dedicated to promoting the rights of Welshwomen, the Welsh language and culture, and organizing charitable projects.

Socialization

Child Rearing and Education. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries children were exploited for labor, sent into mines to work in shafts that were too small for adults. Child and infant mortality rates were high; almost half of all children did not live past the age of five, and only half of those who lived past the age of ten could hope to live to their early twenties. Social reformers and religious organizations, particularly the Methodist Church, advocated for improved public education standards in the mid-nineteenth century. Conditions began to gradually improve for children when working hours were restricted and compulsory education enacted. The Education Act of 1870 passed to enforce basic standards, but also sought to banish Welsh completely from the education system.

Today, primary and nursery schools in areas with a Welsh-speaking majority provide instruction completely in Welsh and schools in areas where English is the first language offer bilingual instruction. The Welsh Language Nursery Schools Movement, Mudiad Ysgolion Meithrin Cymraeg, founded in 1971, has been very successful in creating a network of nursery schools, or Ysgolion Meithrin, particularly in regions where English is used more frequently. Nursery, primary, and secondary schools are under the administration of the education authority of the Welsh Office. Low-cost, quality public education is available throughout Wales for students of all ages.

Higher Education. Most institutions of higher learning are publicly supported, but admission is competitive. The Welsh literary tradition, a high literacy rate, and political and religious factors have all contributed to shaping a culture where higher education is considered important. The principal institute of higher learning is the University of Wales, a public university financed by the Universities Funding Council in London, with six locations in Wales: Aberystwyth, Bangor, Cardiff, Lampeter, Swansea, and the Welsh National School of Medicine in Cardiff. The Welsh Office is responsible for

Town hall of Laugharne, Dyfed, Wales.

the other universities and colleges, including the Polytechnic of Wales, near Pontypridd, and the University College of Wales at Aberystwyth. The Welsh Office, working with the Local Education Authorities and the Welsh Joint Education Committee, oversees all aspects of public education. Adult continuing education courses, particularly those in Welsh language and culture, are strongly promoted through regional programs.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Religion has played a significant role in the shaping Welsh culture. Protestantism, namely Anglicanism, began to gather more support after Henry VIII broke with the Roman Catholic Church. On the eve of the English Civil War in 1642, Puritanism, practiced by Oliver Cromwell and his supporters, was widespread in the border counties of Wales and in Pembrokeshire. Welsh royalists, who supported the king and Anglicanism, were stripped of their property, incurring much resentment among non-Puritan Welsh. In 1650 the Act for the Propagation of the Gospel in Wales was passed, taking over both political and religious life. During the period known as the Interregnum when Cromwell was in power, several non-Anglican, or Dissenting, Protestant congregations were formed which were to have significant influences on modern Welsh life. The most religiously and socially radical of these were the Quakers, who had a strong following in Montgomeryshire and Merioneth, and eventually spread their influence to areas including the Anglican border counties and the Welsh-speaking areas in the north and west. The Quakers, intensely disliked by both other Dissenting churches and the Anglican Church, were severely repressed with the result that large numbers were forced to emigrate to the American colonies. Other churches, such as the Baptist and Congregationalist, which were Calvinist in theology, grew and found many followers in rural communities and small towns. In the latter part of the eighteenth century many Welsh converted to Methodism after a revival movement in 1735. Methodism was supported within the established Anglican Church and was originally organized through local societies governed by a central association. The influence of the original Dissenting churches, combined with the spiritual revival of Methodism, gradually led Welsh society away from Anglicanism. Conflicts in leadership and chronic poverty made church growth difficult, but the popularity of Methodism eventually helped establish it permanently as the most widespread denomination. The Methodist and other Dissenting churches were also responsible for an increase in literacy through church-sponsored schools that promoted education as a way of spreading religious doctrine.

Today, followers of Methodism still constitute the largest religious group. The Anglican Church, or the Church of England, is the second largest sect, followed by the Roman Catholic Church. There are also much smaller numbers of Jews and Muslims. The Dissenting Protestant sects, and religion in general, played very important roles in modern Welsh society but the number of people who regularly participated in religious activities dropped significantly after World War II.

Rituals and Holy Places. The Cathedral of Saint David, in Pembrokeshire, is the most significant national holy place. David, the patron saint of Wales, was a religious crusader who arrived in Wales in the sixth century to spread Christianity and convert the Welsh tribes. He died in 589 on 1 March, now celebrated as Saint David's Day, a national holiday. His remains are buried in the cathedral.

Medicine and Health Care

Health care and medicine are government-funded and supported by the National Health Service of the United Kingdom. There is a very high standard of health care in Wales with approximately six medical practitioners per ten thousand people. The Welsh National School of Medicine in Cardiff offers quality medical training and education.

Secular Celebrations

During the nineteenth century, Welsh intellectuals began to promote the national culture and traditions, initiating a revival of Welsh folk culture. Over the last century these celebrations have evolved into major events and Wales now has several internationally important music and literary festivals. The Hay Festival of Literature, from 24 May to 4 June, in the town of Hay-on-Wye, annually attracts thousands, as does the Brecon Jazz Festival from 11 to 13 August. The most important Welsh secular celebration, however, is the Eisteddfod cultural gathering celebrating music, poetry, and storytelling.

The Eisteddfod has its origins in the twelfth century when it was essentially a meeting held by the Welsh bards for the exchange of information. Taking place irregularly and in different locations, the Eisteddfod was attended by poets, musicians and troubadours, all of whom had important roles in medieval Welsh culture. By the eighteenth century the tradition had become less cultural and more social, often degenerating into drunken tavern meetings, but in 1789 the Gwyneddigion Society revived the Eisteddfod as a competitive festival. It was Edward Williams, also known as Iolo Morgannwg, however, who reawakened Welsh interest in the Eisteddfod in the nineteenth century. Williams actively promoted the Eisteddfod among the Welsh community living in London, often giving dramatic speeches about the significance of Welsh culture and the importance of continuing ancient Celtic traditions. The nineteenth century revival of the Eisteddfod and the rise of Welsh nationalism, combined with a romantic image of ancient Welsh history, led to the creation of Welsh ceremonies and rituals that may not have any historical basis.

The Llangollen International Musical Eisteddfod, held from 4 to 9 July, and the Royal National Eisteddfod at Llanelli, which features poetry and Welsh folk arts, held from 5 to 12 August, are the two most important secular celebrations. Other smaller, folk and cultural festivals are held throughout the year.

A half-timbered building in Beaumaris, Anglesey, Wales.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. The traditional importance of music and poetry has encouraged a general appreciation of and support for all of the arts. There is strong public support throughout Wales for the arts, which are considered important to the national culture. Financial support is derived from both the private and public sectors. The Welsh Arts Council provides government assistance for literature, art, music, and theater. The council also organizes tours of foreign performance groups in Wales and provides grants to writers for both English- and Welsh-language publications.

Literature. Literature and poetry occupy an important position in Wales for historical and linguistic reasons. Welsh culture was based on an oral tradition of legends, myths, and folktales passed down from generation to generation. The most famous early bardic poets, Taliesin and Aneirin, wrote epic poems about Welsh events and legends around the seventh century. Increasing literacy in the eighteenth century and the concern of Welsh intellectuals for the preservation of the language and culture gave birth to modern written Welsh literature. As industrialization and Anglicization began to threaten traditional Welsh culture, efforts were made to promote the language, preserve Welsh poetry, and encourage Welsh writers. Dylan Thomas, however, the best known twentieth century Welsh poet, wrote in English. Literary festivals and competitions help keep this tradition alive, as does the continued promotion of Welsh, the Celtic language with the largest number of speakers today. Nevertheless, the influence of other cultures combined with the ease of communication through mass media, from both inside the United Kingdom and from other parts of the world, continually undermine efforts to preserve a purely Welsh form of literature.

Performance Arts. Singing is the most important of the performance arts in Wales and has its roots in ancient traditions. Music was both entertainment and a means for telling stories. The Welsh National Opera, supported by the Welsh Arts Council, is one of the leading opera companies in Britain. Wales is famous for its all-male choirs, which have evolved from the religious choral tradition. Traditional instruments, such as the harp, are still widely played and since 1906 the Welsh Folk Song Society has preserved, collected, and published traditional songs. The Welsh Theater Company is critically acclaimed and Wales has produced many internationally famous actors.

The State of Physical and Social Sciences

Until the last part of the twentieth century, limited professional and economic opportunities caused many Welsh scientists, scholars, and researchers to leave Wales. A changing economy and the investment of multinationals specializing in high technology are encouraging more people to remain in Wales and find work in the private sector. Research in the social and physical sciences is also supported by Welsh universities and colleges.

Bibliography

Curtis, Tony. Wales: The Imagined Nation, Essays in Cultural and National Identity, 1986.

Davies, William Watkin. Wales, 1925.

Durkaez, Victor E. The Decline of the Celtic Languages: A Study of Linguistic and Cultural Conflict in Scotland, Wales and Ireland from the Reformation to the Twentieth Century, 1983.

English, John. Slum Clearance: The Social and Administrative Context in England and Wales, 1976.

Fevre, Ralph, and Andrew Thompson. Nation, Identity and Social Theory: Perspectives from Wales, 1999.

Hopkin, Deian R., and Gregory S. Kealey. Class, Community, and the Labour Movement: Wales and Canada, 1989.

Jackson, William Eric. The Structure of Local Government in England and Wales, 1966.

Jones, Gareth Elwyn. Modern Wales: A Concise History, 1485–1979, 1984.

Owen, Trefor M. The Customs and Traditions of Wales, 1991.

Rees, David Ben. Wales: The Cultural Heritage, 1981.

Williams, David. A History of Modern Wales, 1950.

Williams, Glanmor. Religion, Language, and Nationality in Wales: Historical Essays by Glanmor Williams, 1979.

Williams, Glyn. Social and Cultural Change in Contemporary Wales, 1978.

——. The Land Remembers: A View of Wales, 1977.