Culture of Vanuatu

Culture Name

Ni-Vanatu

Orientation

Identification. The name "Vanuatu" is an important aspect of national identity. Leaders of the Vanua'aku Party, which led the first independent government, invented the term in 1980 to replace the colonial name New Hebrides. Vanua means "land" in many of Vanuatu's one hundred five languages, and translations of the new name include "Our Land" and "Abiding Land." Culturally, Vanuatu is complex. Some of the people follow matrilineal descent rules, while others follow patrilineal rules. Leadership on some islands depends on advancement within men's societies, and in others it depends on possession of chiefly titles or personal ability. Although most people depend on subsistence farming and fishing, the economy of the seaboard differs from that of interior mountain plateaus.

Political leaders have consciously cultivated national culture to foster a national identity, including political slogans such as "Unity in Diversity." Many rural people, however, are attached primarily to their home islands, while educated urbanites, refer to supranational identities such as Melanesian.

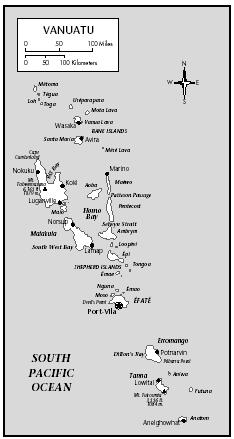

Location and Geography. Vanuatu is a Y-shaped tropical archipelago of over eighty islands, sixty-five of which are inhabited. The Solomon Islands lie to the north, New Caledonia to the south, Fiji to the east, and the Coral Sea and Australia to the west. The mostly volcanic archipelago extends 560 miles (900 kilometers) from north to south and has an area of 5,700 square miles (14,760 square kilometers). Espiritu Santo is the largest island. Port Vila, the capital, which was also the colonial headquarters, is on the south-central island of Efate.

Demography. The 1997 population of 185,000 is 94 percent Melanesian, 4 percent European (mostly French), and 4 percent other (Vietnamese, Chinese, and other Pacific Islander).

Linguistic Affiliation. Bislama, the nation's pidgin English which emerged in the nineteenth century, is essential for public discourse. Many aspects of the national culture are phrased in Bislama, which has become an important marker of national identity. Alongside Bislama, English and French are recognized as "official languages." These languages overlie one hundred five indigenous Austronesian languages, three of which are Polynesian in origin. There are strong links between local language, place, and identity, but many people are multilingual. Most children pursue elementary schooling in English or French, although few residents are fluent in either language. Most national discourse takes place in Bislama, which is becoming creolized.

Symbolism. The politicians who forged independence emphasized shared culture ( kastom ) and shared Christianity to create a national identity and iconography. The national motto is Long God Yumi Stanap ("In (or with) God We Stand/Develop"). Leaders of the Vanua'aku Party, which governed during the nation's first eleven years, came mostly from the central and northern areas. Objects selected to represent the nation come principally from those regions, including circle pig tusks, palm leaves, and carved slit gongs. The name of the national currency, the vatu ("stone") derives from central northern languages, as does the name "Vanuatu." After independence, holidays were established to celebrate the nation and promote national identity and unity.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. The New Hebrides was a unique "condominium" colony ruled jointly by Great Britain and France after 1906. Although they instituted a joint court and a few other combined services, each ran separate and parallel administrative

Vanuatu

bureaucracies, medical systems, police forces, and school systems. Competition and conflict between Anglophones and Francophones culminated in the 1970s, when both groups backed different political parties in the run-up to independence. The French had greatly expanded their educational system, leaving a legacy of Francophones who commonly find themselves opposed politically to their Anglophone compatriots.

The main parties in favor of independence in the 1970s were British-supported and Anglophone, drawing on English and Protestant roots more than on French and Roman Catholic. Still, all the citizens distinguish themselves from European colonialists as they assume their national identity. Since independence, the French have provided aid in periods when the country has been ruled by Francophone political parties. Australia and New Zealand have largely replaced British assistance and influence.

Ethnic Relations. A relatively small population of Vietnamese (which the French recruited as plantation workers beginning in the 1920s) and overseas Chinese control a significant proportion of the economies of Port Vila and Luganville. These wealthy families are linked by kinship, economic, and other relations with the majority Melanesian population.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

Vanuatu is still a rural country. Most ni-Vanuatu live on their home islands, although the population of the two towns has increased significantly since independence. Town layout and architecture reflect French and British sensibilities. A huge American military base that grew up around Luganville during the World War II still displays that heritage. Rural architecture remains largely traditional. Local notions of gender and rank influence village layout. Women's mobility is more restricted than that of men, and in many churches, men and women sit on opposite sides of a central aisle. People use "bush" materials in the construction of housing, although they also use cement brick and aluminum sheet roofing. Houses have one or two rooms for sleeping and storage. Cooking is done in fireplaces or lean-to kitchens outdoors.

After independence, the government erected several public buildings, including a national museum, the House of Parliament, and the House of Custom Chiefs. These buildings incorporate slit gongs and other architectural details that display the cultural heritage. The latter two also model the traditional nakamal (men's house or meeting ground), a ritual space where public discussion and decision making take place. In many cultures, men and occasionally women retire each evening to the nakamal to prepare and drink kava, an infusion of the pepper plant. Scores of urban kava bars have opened in Port Vila, Luganville, and government centers around the islands. Employed urbanites gather there at the end of the day, just as their rural kin congregate at nakamal on their home islands.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Ni-Vanuatu combine traditional south Pacific cuisine with introduced elements. Before contact with the West, staple foods included yam, taro, banana, coconut, sugarcane, tropical nuts, greens, pigs, fowl, and seafood. After contact, other tropical crops (manioc, plantain, sweet potato, papaya, mango) and temperate crops (cabbage, beans, corn, peppers, carrots, pumpkin) were added to the diet. Rural people typically produce most of what they eat, supplementing this with luxury foods (rice and tinned fish) purchased in stores. The urban diet relies on rice, bread, and tinned fish supplemented with rural products. Port Vila, and Luganville have restaurants that serve mostly the foreign and tourist communities.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Ceremonies typically involve an exchange of food, such as the traditional taro and yam, kava, fowl, pigs, and chicken, along with a feast. Pigs are exchanged and eaten at all important ritual occasions. The national ceremonial dish is laplap , pudding made of grated root crops or plantain mixed with coconut milk and sometimes greens and meat, wrapped in leaves, and baked for hours in a traditional earth oven. In rural areas, during the week many people rely on simple boiling to cook roots and greens. On weekends, they prepare earth ovens and bake laplap for the evening meal and a Sunday feast. The exchange, preparation, and consumption of kava are integral parts of ceremonial occasions.

Basic Economy. Most ni-Vanuatu are subsistence farmers who do cash cropping on the side. The mode of production is swidden ("slash-and burn") horticulture, with farmers clearing and then burning new forest plots each season. Vanuatu has significant economic difficulties. Transportation costs are high, the economic infrastructure is undeveloped, and cyclone damage is common. Major export crops include copra, beef, tropical woods, squash, and cacao. Vanuatu is a tax haven that earns income from company registrations and fees and an offshore shipping registry. Tourism has become a major growth area. The government remains the largest employer of wage labor, and few employment activities exist outside the towns and regional government centers.

Land Tenure and Property. After independence, all alienated plantation land reverted to the customary owners. Only citizens may own land, although they can lease it to foreigners and investors. Generally, land belongs jointly to the members of lineages or other kin groups. Men typically have greater management fights to land than do women, although women may control land, particularly in matrilineal areas.

Commercial Activities, Major Industries, and Trade. Rural families produce cash crops (coconut, cacao, coffee, and foodstuffs) for sale in local markets. The opening of urban kava bars has stimulated an internal market for kava. With the growing tourist industry, there is a small market for traditional handicrafts, including woven baskets and mats, wood cavings, and jewelry. Manufacturing and industry contribute only 5 to 9 percent of the gross domestic product, and this mostly consists of fish, beef, and wood processing for export. The major trade partners are Australia, Japan, France, New Zealand, and New Caledonia

Social Stratification

Chiefly status exists in many of the indigenous cultures, though differences between chiefly and commoner lineages are slight. Symbolically, a man and his family's possession of a title is often marked in details of dance costume, adornment, and architecture. Leadership in the north rests largely on a man's success in "graded societies" which able individuals work their way up a ladder of status grades by killing and exchanging circle-tusked pigs. In the central and southern regions, the acquisition of titles also depends on individual effort and ability. Everywhere leadership correlates with ability, gender, and age, with able, older men typically being the most influential members of their villages.

Since rural society is still rooted in subsistence agriculture, economic and political inequalities are muted. However, there is increasing economic stratification between the educated and employed, most of whom live in urban areas, and rural subsistence farmers. The middle-class elite is relatively small, and urbanites remain connected by important kin ties to their villages.

Political Life

Government. Vanuatu is a republic with a unicameral parliament with fifty seats. An electoral college elects a nonexecutive president every five years. There are six regions whose elected councils share responsibility for local governance with the national government. An elected national council of chiefs, the Malvatumaori, advises the parliament on land tenure and customs.

Leadership and Political Officials. Since independence, elected officials have mostly been educated younger men who were originally pastors and leaders of Christian churches. The elders remain in the islands, serving as village chiefs, though the

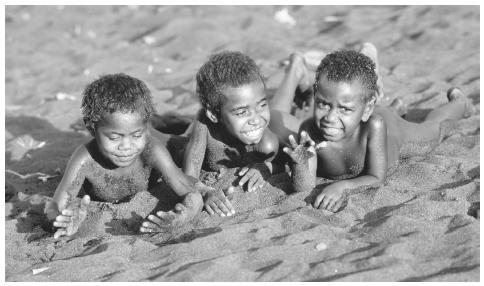

Children from the Jon Frum Cargo Cult Village play in the black sand beach on Tanna Island, which is a short distance from the active volcano Yasur. Vanuatu is a mostly volcanic archipelago of over eighty islands.

country's prime ministers, presidents, and members of parliament have typically acquired honorary chiefly titles from various regions.

Social Problems and Control. The pattern of "circular migration" between rural village and urban center from the colonial era has broken down as more people have become permanent residents of Port Vila and Luganville. Many underemployed people live in periurban settlements, and urban migration has correlated with increasing rates of burglary and other property crimes. Demonstrations associated with political factions occur occasionally. The urban crime rate is very low.

An informal system of "town chiefs" supplements the state police force and judiciary. Leading elders in the towns meet to resolve disputes and punish offenders. Punishment sometimes involves the informal banishment of an accused person back to his or her home island. Unofficial settlement procedures frequently are used to handle disputes in rural areas.

Military Activity. The Vanuatu Mobile Force has been active only occasionally, mostly in international endeavors such as serving as peacekeepers.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

State and nongovernmental organizations have focused on developing economic infrastructure and public services. Most villages have no electricity, and many people lack access to piped water despite efforts to expand rural water systems. Several organizations work with rural youth and women. The National Council of Women sponsors programs to improve women's access to the cash economy and reduce domestic violence.

A number of international and nongovernmental organizations are active in Vanuatu. Many international donors are encouraging a comprehensive reform program to make government more efficient and honest and lower deficit spending.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

The principal nongovernmental organizations are the Christian churches. Religious affiliation is second in importance only to kinship and neighborhood ties. A few labor unions have attempted to organize urban and rural salaried workers (such as schoolteachers) but have not been effective in industrial action and political campaigning.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Generally, women have less control of land and other property, are less mobile, and have less of a say in marriage. In the northern region, women participate in graded societies that parallel those of men. In matrilineal regions, women have better land and sea rights. Many ni-Vanuatu continue to believe in the deleterious, polluting effects of menstrual blood and other body fluids, and men and women sleep apart during women's menstrual periods, when women often give up cooking. Both men and women farm, although men are responsible for clearing forest and brush for new garden plots. Both men and women fish and reef gather, though only men undertake deep-sea fishing. Although women have excelled in the school system, men continue to monopolize economic and political leadership positions. Few women drive cars, and only a handful have been elected to the parliament and the regional and town councils. Women do much of the work in town and roadside marketplaces.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. The marriage rate approaches 100 percent. Traditionally, leaders of kin groups arrange the marriages of their children. Marriage is an important event in ongoing exchange relations between kin groups and neighborhoods and typically involves the exchange of goods. Some educated urban residents have adopted Western notions of romantic love and arrange their own marriages with or without family approval. Marriage rules identify certain kin groups as the source of appropriate spouses. In the southern region, marriage is patterned as "sister exchange," in which a man who marries a woman from another family owes a woman in return. In some cases, this woman is an actual sister who marries one of her brother's new wife's brothers; in other cases, the woman is a classificatory sister or even a future daughter. In other areas, notable amounts of goods (bride wealth) change hands, including money, pigs, kava, mats, food, and cotton cloth. Traditionally, powerful leading men might marry polygynously, although after missionization, monogamy became the norm. There are three types of marriages: religious, civil, and "customary." Divorce rates are very low.

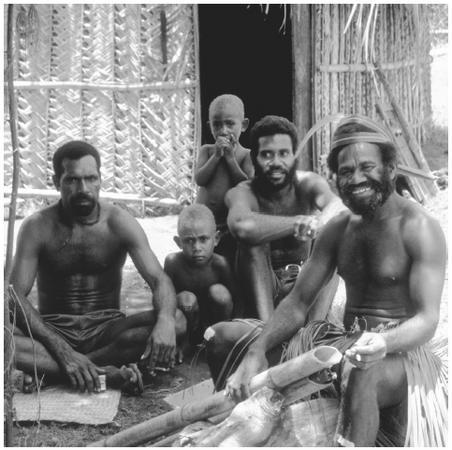

Domestic Unit. The nuclear family is the principal domestic unit, forming the basic household and being responsible for day-to-day economic production and consumption. Households, however, continue to rely on extended kin groups in significant

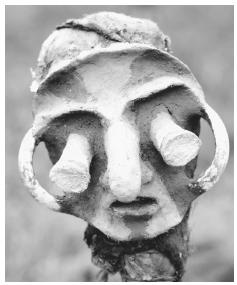

A mask from Vanuatu. There is a strong belief in the power of ancestral spirits.

ways. Most people's access to land and sea rights derives from membership in lineages and clans. People call on extended kin as a labor pool when they build new houses, clear garden land, and raise money and collect goods for family exchanges (marriage, child initiation, funerals). Residence typically is patrivirilocal. Women move to live with their new husbands, who themselves live with their fathers' families. Formerly, many men and initiated boys lived in separate men's houses; today families typically live together as one unit. Both spouses may be involved in managing family affairs; men, however, citing custom and Christian scripture, typically assert basic authority their families.

Inheritance. Except in urban areas, where inheritance is modeled on European precedent, people follow local customs. Land rights pass patrilineally or matrilineally to surviving members of kin groups. In some areas, people destroy much of dead person's goods. Surviving spouses and children inherit what is left.

Kin Groups. Families are organized into larger patrilineages or matrilineages, patricians or matriclans, and moieties. Lineages tend to be localized in one or two villages, as kin live together on or near lineage land. The membership of larger clans is dispersed across a region or island.

Socialization

Infant Care. Babies often nurse until they are three years old. Both parents are involved in child care, but siblings, especially older sisters, do much of the carrying, feeding, and amusing of infants. Babies are held by caregivers almost constantly until they can walk. Physical punishment of children is not common. Younger children may strike their older siblings, while older siblings are restrained from hitting back.

Child Rearing and Education. Many communities and ensure the growth of children through ritual initiation ceremonies that involve the exchange of pigs, mats, kava, and other goods between a child's father's and mother's families. Boys age six to twelve typically undergo circumcision as part of a ritual event.

Most children receive several years of primary education in English or French. Many walk to the nearest school or board there during the week. Less than 10 percent of children go on to attend one of the twenty-seven secondary schools.

Higher Education. Tertiary education includes a teachers' training college, an agricultural school, several church seminaries, and a branch of the University of the South Pacific in Port Vila. A few students pursue university education abroad. The adult literacy rate has been estimated at 55 to 70 percent.

Etiquette

Customary relationships are lubricated by the exchange of goods, and visitors often receive food and other gifts that should be reciprocated. Lines in rural stores are often amorphous, but clerks commonly serve overseas visitors first. People passing on the trails or streets commonly greet one another, and the handshake is an important aspect of initial encounters. A woman traveling alone through the countryside may receive unwelcome attention from men.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Most families have been Christian since the late nineteenth century. The largest denominations are Presbyterian, Anglican, Roman Catholic, Seventh-Day Adventist, and Church of Christ. Baha'i and Mormon missionaries have attracted local followings. Some people reject Christianity and retain traditional religious practices. Others belong to syncretic religious organizations that mix Christianity and local belief. Nearly everyone maintains firm beliefs in the power and presence of ancestral spirits.

Religious Practitioners. Christian priests, ministers, pastors, and deacons lead weekly services and conduct marriages and funerals. A number of people are recognized as clairvoyants and diviners, working sometimes within and sometimes outside the Christian churches. These people, who are often women, divine the causes of disease and other misfortunes, locate lost objects, and sometimes undertake antisorcery campaigns to uncover poesen (sorcery paraphernalia) hidden in a village. Other people specialize in rain, wind, earthquake, tidal wave, and other sorts of magical practice. Many ni-Vanuatu also suspect the existence of sorcerers.

Rituals and Holy Places. Ni-Vanuatu celebrate the Christian calendar, particularly the Christmas and New Year's season, which they call Bonane .At the year's end, urbanites return to their home islands. In villages, people form choruses and visit neighboring hamlets to perform religious and secular songs.

Ni-Vanuatu continue to celebrate traditional holidays. In many places, islanders organize first-fruit celebrations, particularly for the annual yam crop. The most spectacular celebration is the "land jump" on southern Pentecost Island. Tourists sometimes attend other traditional rites, such the dancing and feasting that accompany male initiation and grade-taking ceremonies in many of the cultures and the Toka (or Nakwiari ), a large-scale exchange of pigs and kava celebrated with two days of dancing.

Every community recognizes important places associated with ancestral and other spirits. These "taboo places" may be mountain peaks, offshore reef formations, or rocky outcroppings. People avoid these locations or treat them with respect.

Death and the Afterlife. Nearly all families turn to Christian funerary ritual to bury their dead. Ancestral ghosts continue to haunt their descendants. Many people experience their spiritual presence and receive their advice in dreams.

Medicine and Health Care

The national health service emerged from the separate French and British colonial systems. Most sick people turn initially to local diviners and healers

Villagers congregate in the protection of the shade on Ambrym Island. Households rely on extended kin groups.

who determine whether the source of disease is supernatural or natural and concoct medicines. Folk pharmacology includes hundreds of medical recipes, mostly infusions of leaves and other plant material.

Secular Celebrations

In addition to Independence Day (30 July), Constitution Day (5 October), and Unity Day (29 November), the government has established Family Day (26 December) and Custom Chiefs Day (5 March). Organized and impromptu sports matches are popular, as are money-raising carnivals, agricultural fairs, and arts festivals.

The Arts and Humanities

Literature. Although nineteenth-century missionaries created orthographies and dictionaries for some of the languages, indigenous literature is mostly oral. Ni-Vanuatu appreciate oratory and storytelling and have large archives of oral tales, myths, and legends. Since independence, an orthography committee has attempted to standardize Bislama spelling. Publications mostly consist of biblical material and newspapers, newsletters, and pamphlets. Writers working in English or French have published poems and short stories, particularly at the University of the South Pacific.

Graphic Arts. The tourist industry supports an active cottage handicraft and carving industry, including woven baskets and dyed mats, bark skirts, penis wrappers, miniature slit-gongs and other carvings, shell jewelry, bamboo flutes and panpipes. A few art galleries in Port Vila sell the work of local artists.

Performance Arts. The string band is the preeminent musical genre. Hundreds of bands perform at village dances and weddings, and their music has been important in the emergence of a national culture. Young musicians sing of local and national issues in local languages and Bislama. Popularized on cassette tapes or broadcast on the two radio stations, some of those songs have become national standards. Many bands travel to Port Vila in June to compete in an annual competition. Small community theater organizations whose dramas often address national issues perform in Port Vila, and occasionally tour the hinterlands.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

Several international research associations, such as France's ORSTOM, have studied agriculture, volcanism, geology, geography, and marine biology in Vanuatu. A local amateur society, the Vanuatu Natural Science Society, emphasizes ornithology. The University of the South Pacific Centre in Port Vila houses that university's Pacific languages unit and law school. The Vanuatu Cultural Center supports a succesful local fieldwork program in which men and women are trained to study and document anthropological and linguistic information.

Bibliography

Allen, Michael, ed. Vanuatu: Politics, Economics and Ritual in Island Melanesia , 1981.

Bonnemaison, Joël. The Tree and the Canoe: History and Ethnography of Tanna , 1994.

——, Kirk Huffman, Christian Kaufmann, and Darrell Tryon, eds. Arts of Vanuatu , 1996.

Coiffier, Christine. Traditional Architecture in Vanuatu , 1988.

Crowley, Terry. Beach-La-Mar to Bislama: The Emergence of a National Language in Vanuatu , 1991.

Foster, Robert J., ed. Nation Making: Emergent Identities in Postcolonial Melanesia , 1995.

Haberkorn, Gerald. Port Vila: Transit Station or Final Stop? , 1989.

Jolly, Margaret. Women of the Place: Kastom, Colonialism and Gender in Vanuatu , 1994.

Lindstrom, Lamont. Knowledge and Power in a South Pacific Society , 1990.

Lini, Walter. Beyond Pandemonium: From the New Hebrides to Vanuatu , 1980.

McClancy, Jeremy. To Kill a Bird with Two Stones: A Short History of Vanuatu , 1980.

Miles, William F. S. Bridging Mental Boundaries in a Postcolonial Microcosm: Identity and Development in Vanuatu , 1998.

Rodman, Margaret C. Masters of Tradition: Consequences of Customary Land Tenure in Longana, Vanuatu , 1987.

Van Trease, Howard, ed. Melanesian Politics: Stael Blong Vanuatu , 1995.

Weightman, Barry. Agriculture in Vanuatu: A Historical Review , 1989.