Culture of Ukraine

Culture Name

Ukrainian

Orientation

Identification. Ukrainian nationhood begins with the Kyivan Rus. This Eastern Slavic state flourished from the ninth to the thirteenth centuries on the territory of contemporary Ukraine, with Kyiv as its capital. The name Ukraine first appeared in twelfth century chronicles in reference to the Kyivan Rus. In medieval Europe cultural boundary codes were based on a native ground demarcation. Ukraine, with its lexical roots kraj (country) and krayaty (to cut, and hence to demarcate), meant "[our] circumscribed land." The ethnonym Rus was the main self-identification in Ukraine until the seventeenth century when the term Ukraine reappeared in documents. This ethnonym of Rus people, Rusych (plural, Rusychi ), evolved into Rusyn , a western Ukrainian self-identification interchangeable with Ukrainian into the twentieth century. Ruthenian , a Latinization of Rusyn , was used by the Vatican and the Austrian Empire designating Ukrainians.

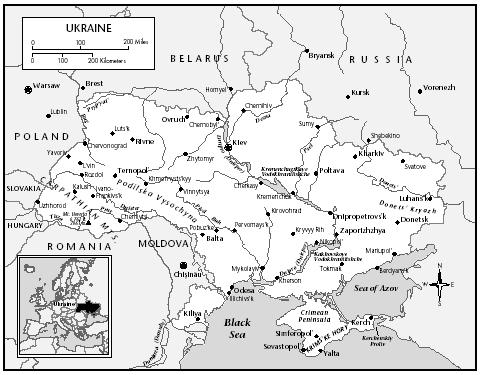

Location and Geography. Ukraine, Europe's second largest country during the twentieth century, occupies 232,200 square miles (603,700 square kilometers). Its main geographical features are the Polissya and Volyn northern forests, the central forest steppes, the Donetsk eastern uplands (up to 1,600 feet [500 meters] above sea level), and the coastal lowlands and steppes along the Black and Azov Seas. The Carpathian mountains in the west reach 6,760 feet (2,061 meters) at Mount Hoverla. Roman-Kosh in the Crimean peninsula reaches 5,061 feet (1,543 meters.) Alpine meadows—called polonyna in the Carpathians and iajla in the Crimea—are another interesting geographical feature.

Ukraine's climate is moderate. The yearly average temperatures range from 40 to 49 degrees Fahrenheit (6 to 9 degrees Celsius)—except for the southern steppes and in Crimea, where yearly average temperatures range from 50 to 56 degrees Fahrenheit (10 to 13 degrees Celsius).

Ukraine has twenty-four administrative units—oblasts—almost all named for their capitals. From east to west, they are Donetsk, Luhansk, Kharkiv, Poltava, Zaporizhzhya, Dnipropetrovsk, Kirovohrad, Kherson, Mykolaiv, Odessa, Cherkasy, Kyiv, Sumy, Chernihiv, Zhytomyr, Vinnytsya, Rivne, Luts'k (Volyns'ka oblast'), Khmel'nyts'kyj, Ternopil', Lviv, Ivano-Frankivs'k, Uzhhorod (Zakarpats'ka oblast'), and Chernivtsi. The Crimean oblast became an autonomous republic in 1991.

Ukraine's regional ethnographic cultures, not always congruent with oblast boundaries are: Donbas, Slobozhanshchyna, Zaporizhzhya, Steppes Ukraine, Poltava, Cherkasy, Polissya, Podillya, Volyn, Halychyna, Bukovyna, Transcarpathia, and Crimea. Crimean Tatar culture predominates in Crimea, and the Hutsul highlanders live in Halychyna, Bukovyna, and Transcarpathia.

Demography. Ukraine's 1989 census showed a population of 51,452,000. A negative population growth was probably caused by economic and environmental crises, including the Chernobyl disaster. The 1989 census shows the following percentages of the population's ethnic composition: Ukrainians, 72.7 percent; Russians, 22.1 percent; Jews, 0.9 percent; Belorussians, 0.8 percent; Moldovans, 0.6; Poles, 0.5 percent; Bulgarians, 0.4 percent; Hungarians, 0.3 percent; Crimean Tatars, 0.2 percent; Romanians, 0.2 percent; Greeks, 0.2 percent; Armenians, 0.1 percent; Roma (Gypsies), 0.1 percent; Germans, 0.1 percent; Azerbaijanis, 0.1 percent; Gagauz, 0.1 percent; and others, 0.5 percent.

Linguistic Affiliation. Ukrainian is an Indo-European language of the Eastern Slavic group. Its Cyrillic alphabet is phonetic; its grammar is synthetic, conveying information through word modification rather than order. Contemporary literary Ukrainian

Ukraine

developed in the eighteenth century from the Poltava and Kyiv dialects. Distinctive dialects are the Polissya, Volyn, and Podillya dialects of northern and central Ukraine and the western Boyko, Hutsul, and Lemko dialects. Their characteristics derive from normatively discarded old elements that reappear in dialectic usage. The surzhyk, an unstable and variable mixture of Ukrainian and Russian languages, is a by-product of Soviet Russification. A similar phenomenon based on Ukrainian and Polish languages existed in western Ukraine but disappeared almost completely after World War II.

In 1989 statistics showed Ukrainian spoken as a native language by 87 percent of the population, with 12 percent of Ukrainians claiming Russian as their native language. The use of native languages among ethnic groups showed Russians, Hungarians, and Crimean Tatars at 94 to 98 percent and Germans, Greeks, and Poles at 25 percent, 19 percent and 13 percent, respectively. Assimilation through Ukrainian language is 67 percent for Poles, 45 percent for Czechs, and 33 percent for Slovaks. As a second language Ukrainian is used by 85 percent of Czechs, 54 percent of Poles, 47 percent of Jews, 43 percent of Slovaks, and 33 percent of Russians.

Formerly repressed, Ukrainian and other ethnic languages in Ukraine flourished at the end of the twentieth century. Ukrainian language use grew between 1991 and 1994, as evidenced by the increase of Ukrainian schools in multiethnic oblasts. However, local pro-communist officials still resist Ukrainian and other ethnic languages except Russian in public life.

Symbolism. The traditional Ukrainian symbols—trident and blue-and-yellow flag—were officially adopted during Ukrainian independence in 1917–1920 and again after the declaration of independence in 1991. The trident dates back to the Kyivan Rus as a pre-heraldic symbol of Volodymyr the Great. The national flag colors are commonly believed to represent blue skies above yellow wheat fields. Heraldically, they derive from the Azure, the lion rampant or coat of arms of the Galician Volynian Prince Lev I. The 1863 patriotic song "Ukraine Has Not Perished," composed by Myxaylo Verbyts'kyi from a poem of Pavlo Chubyns'kyi, became the Ukrainian national anthem in 1917 and was reaffirmed in 1991. These symbols were prohibited as subversive under the Soviets, but secretly were cherished by all Ukrainian patriots.

The popular symbol of Mother Ukraine appeared first in Ukrainian baroque poetry of the seventeenth century as a typical allegory representing homelands as women. When Ukraine was divided between the Russian and Austrian empires, the image of Mother Ukraine was transformed into the image of an abused woman abandoned by her children. Mother Ukraine became a byword, not unlike Uncle Sam, but much more emotionally charged. After 1991 a new generation of Ukrainian writers began to free this image from its victimization aspects.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. Ukrainian nationhood begins with the Kyivan Rus realm, which arose from a unification of Antian tribes between the sixth and ninth centuries. Rus is mentioned for the first time by European chroniclers in 839 C.E. The Kyivan state experienced a cultural and commercial flourishing from the ninth to the eleventh centuries under the rulers Volodymyr I (Saint Volodymyr), his son Yaroslav I the Wise, and Volodymyr Monomakh. The first of these rulers Christianized Rus in 988 C.E. The other two gave it a legal code. Christianity gave Rus its first alphabet, developed by the Macedonian saints Cyril and Methodius. Dynastic fragmentation and Mongol and Tatar invasions in the thirteenth century caused Kyiv's decline. The dynastically related western principality of Halych (Galicia) and Volyn resisted the Mongols and Tatars and became a Rus bastion through the fourteenth century. One of its most distinguished rulers was Danylo Romanovich, the only king in Ukrainian history, crowned by the Pope Innocent IV in 1264.

After the fourteenth century, Rus fell under the rule of foreign powers: the Golden Horde Mongols, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the kingdom of Poland. Lithuania controlled most of the Ukrainian lands except for the Halych and Volyn principalities, subjugated after much struggle by Poland. The southern steppes and the Black Sea coast remained under the Golden Horde, an outpost of Genghis Khan's empire. The Crimean khanate, a vassal state of the Ottomans, succeeded the Golden Horde after 1475. Eventually northwestern and central Ukraine were absorbed into the Grand Duchy of Lithuania which then controlled almost all of Ukraine—giving Ukrainians and Belorussians ample autonomy. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania adopted the administrative practices and the legal system of Rus and a state language that was Old Slavonic, heavily imbued with vernacular Ukrainian and Belorussian. However, Lithuania—united with Poland by a dynastic linkage in 1386—gradually adopted Roman Catholicism and Polish language and customs. In 1569 the Lublin Union created the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and Ukraine was annexed to Poland. The 1596 Brest-Litovsk Union divided Ukrainians into Orthodox and Uniate Catholics. Northern borderlands initially colonized by Rus princes increasingly diverged from the Kyivan culture with the rise of the Duchy of Muscovy.

In the fifteenth century Ukraine clashed with the Crimean Khanate. The 1490 chronicles mention Ukrainian warriors called kozaks defending Ukrainian lands from Crimean Tatar slave raids. Kozaks were based on the Zaporozhian Sich, an island fortress below the Dnipro River rapids. Nominally subject to the Polish crown, the Zaporozhian kozaks became symbols of Ukrainian national identity. Strife between the Ukrainians and their Polish overlords began in the 1590s, spearheaded by the kozaks. In 1648, led by the kozak hetman (military leader) Bohdan Khmelnytsky, Ukrainians rose against Poland, forming an independent state. Khmelnytsky sought help against the Poles in a treaty with Moscow in 1654, which was used as a pretext for occupation by the Muscovites. Poland recognized Moscow's suzerainty over Kiev and the lands east of the Dnipro, and the Ukrainian hetmanate was gradually subjugated by Moscow. Despite this, the hetmanate reached its pinnacle under Ivan Mazepa (1687–1709). Literature, art, architecture in the distinctive Kozak baroque style, and learning flourished under his patronage. Mazepa wanted a united Ukrainian state, initially under the tsar's sovereignty. When Tsar Peter threatened Ukrainian autonomy, Mazepa rose against him in alliance with Charles XII of Sweden. The allies were defeated in the Battle of Poltava in 1709. Fleeing from Peter's vengeance Mazepa and his followers became the first organized political immigration in Ukrainian history.

During the eighteenth-century partitions of Poland, the Russian Empire absorbed all Ukraine except for Galicia, which went to Austria. The empress Catherine II extended serfdom to the traditionally free kozak lands and destroyed the Zaporozhian Sich in 1775. During the nineteenth century all vestiges of nationhood were repressed in Russian-held Ukraine. The Ukrainian language was banned from all but domestic use by the Valuev Decree of 1863 and the Ems Ukase of 1876. Ukrainians opposed this policy by developing strong ties with Ukrainian cultural activists in the much freer Austrian Empire. An inclusive national movement arose during World War I, and in 1917 an independent Ukrainian state was proclaimed in Kyiv. In 1918 western Ukraine declared independence striving to unite with the East, but its occupation by Poland was upheld by the Allies in 1922.

After two years of war Ukraine became part of the Soviet Union in 1922. Its Communist party was subordinated to the Russian Communists. Only 7 percent of its 5,000 members were Ukrainian. Favoring city proletarians—mostly alien in nationality and ideology—the Bolsheviks had very little support in a population 80 percent Ukrainian, and 90 percent peasant. However, Ukrainian communists implemented a policy of Ukrainization through educational and cultural activities. This rebirth of Ukrainian culture ended abruptly at the time of the Stalin's genocidal famine of 1933. This famine killed up to seven million Ukrainians, mostly peasants who had preserved the agricultural traditions of Ukraine along with an ethnic and national identity. The destruction of Ukrainian nationalism and intelligentsia lasted through the Stalinist purges of the late 1930s and continued more selectively until the fall of the Soviet Union.

When Germany and the Soviets attacked Poland in 1939, Galicia was united to the rest of Ukraine. The German-Soviet war in 1941 brought hopes of freedom and even a declaration of independence in western Ukraine. However, the brutal Nazi occupation provoked a resistance movement, first against the Germans and then against the Soviets. The Ukrainian Insurgent Army fought overwhelming Soviet forces that subjected western Ukraine to mass terror and ethnic cleansing to destroy the resistance. At the end of World War II almost three million Ukrainians were in Germany and Austria, most of them forced laborers and prisoners of war. The vast majority of them were forcibly repatriated to the Soviet Union, and ended up in Gulag prison camps. Two-hundred thousand refugees from Ukraine managed to remain in Western Europe and immigrated to the United States and to other Western countries.

In 1986, the Chernobyl accident, a partial meltdown at a Soviet-built nuclear power plant, shocked the entire nation. After Mikhail Gorbachev's new openness policy in the 1980s, the democratized Ukrainian parliament declared the republic's sovereignty in 1990. Following a failed coup against Gorbachev in the Soviet Union, the Ukrainian parliament declared independence on 24 August 1991, overwhelmingly approved by referendum and internationally recognized.

National Identity. National identity arises from personal self-determination shared with others on the basis of a common language, cultural and family traditions, religion, and historical and mythical heritages. There is a lively reassessment of these elements in contemporary Ukraine in a new stage of identity development. Language issues focus on the return of phonetics, purged from Soviet Ukrainian orthography by Russification, and on the macaronic Russo/Ukrainian surzhyk. A revival of cultural traditions includes Christian holidays, days of remembrance, and church weddings, baptisms, and funerals. The Ukrainian Catholic Church emerged from the underground and the exiled Ukrainian Orthodox Autocephalous Church united formally with the Kyivan patriarchy. Ukrainian Protestants of various denominations practice their religion unhampered.

The 988 baptism of the Rus melded Christian beliefs with existing customs, leading to a Rus identity connected to both homeland and religion. In the seventeenth century Ukrainian identity held its own against Polish identity and the Roman Catholic Church. In the Russian empire Ukrainians preserved their identity through culture and language because religion by itself integrated them with Russians.

Historical facts and myths as bases of national identity were first reflected in the literature of the Ukrainian baroque. In later times, the proto-Slavic origins of the Ukrainian people were ascribed to the settled branch of Scythians (500 B.C.E. –100 B.C.E. ) mentioned by ancient Greek and Roman historians. Recent theories connecting origins of Ukrainian culture with the first Indo-European tribes of the Northern Black Sea region and with the Trypillya culture (4,000 B.C.E. ) are supported by plausible research.

Ethnic Relations. Ukraine, surrounded by diverse nations and cultures, is home to Belorussians in northern Polissia; Poles, Slovaks, Hungarians, and Romanians in western Ukraine; Moldovians and

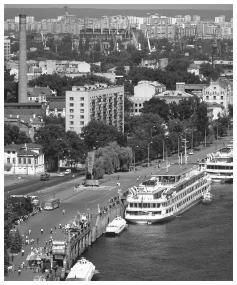

Boats and barges line the Dnieper River in Kiev.

Gagauz in southern Ukraine; and Russians in eastern and northern Ukraine. The Russian Empire settled Germans, Swedes, Bulgarians, Greeks, Christian Albanians, and Serbs in southern steppes. Russian landlords brought ethnic Russian serfs to the steppes, and Russian Old Believers also settled there fleeing persecution. In 1830 and 1863 the Russian government exiled Polish insurgents to southern Ukraine. Serbs and Poles assimilated with Ukrainians, but the other groups retained their identities. Tatars, Karaims, and Greeks were native to Crimea. Since the Middle Ages Jews and Armenians settled in major and minor urban centers. Roma (Gypsies) were nomadic until Soviets forced them into collective farms. The last major immigration to Ukraine took place under the Soviets. Ethnic Russians were sent to repopulate the villages emptied by the 1933 genocide and again after 1945 to provide a occupying administration in western Ukraine.

Historically, ethnic conflicts emerged in Ukraine on social and religious grounds. The seventeenth century Ukrainian-Polish wars were caused by oppressive serfdom, exorbitant taxes, and discrimination or even elimination of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church by Polish magnates. Their appointment of Jewish settlers as tax collectors in Ukrainian villages also led to strife between these ethnic groups. The settled Ukrainians and the nomadic steppe tribes conflicted since medieval times. From the fifteenth century on, Crimean Tatars raided Ukraine for slaves, and Zaporozhian kozaks were the only defense against them. Even so, Zaporozhians made trade and military agreements with the Crimean khanate: Tatar cavalry often assisted Ukrainian hetmans in diverse wars. Likewise, Ukrainian cultural and educational connections with Poles existed despite their conflicts: Bohdan Khmelnytsky and many other kozak leaders were educated in Polish Jesuit colleges, and initially Khmelnytsky considered the Polish king as his liege. Ukrainian Jewish relations of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries also cannot be wholly described in terms of ethnic strife. Jewish merchants regularly traded with kozaks and several high officers of the hetmanate—such as members of the renowned Markevych/Markovych aristocratic families—were of Jewish origin.

In contemporary Ukraine ethnic communities enjoy governmental support for their cultural development. Ethnic language instruction increased considerably in multicultural regions. The first center for preservation and development of Roma culture opened in Izmail near Odessa. Two prominent issues in ethnic relations concern the return to Crimea of the Crimean Tatars exiled in Soviet times and the problem of the Russian-speaking population. The Crimean Tatar Medjlis (parliament) demands citizenship for Tatars returning from Stalinist exile while the Russian-dominated parliament of the Crimean autonomous republic opposes that demand.

Pro-Russian elements identify Russophones with Russian ethnicity. However, statistics show a large number of Russophones who do not consider themselves Russian. In 1989, 90.7 percent of Jews, 79.1 percent of Greeks, and 48.9 percent of Armenians and other ethnic groups in Ukraine recognized Russian as a language of primary communication but not an indicator of ethnicity or nationality. Forcing a Russian ethnic identity onto non-Russian Russophones infringes on their human rights. Russians in Ukraine are either economic migrants from Soviet times, mostly blue-collar workers, or the former Russian nomenklatura (bureaucratic, military, and secret police elite). The latter were the upper class of Soviet society. Since losing this status after the Soviet Union collapsed, they have rallied around a neo-Communist, pro-Russian political ideology, xenophobic in the case of the Crimean Tatars.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

A prototypical architectural tradition was found by archeologists studying ancient civilizations in Ukraine. Excavations of the Tripillya culture (4,000–3,000 B.C.E. ) show one- and two-room houses with outbuildings within concentric walled and moated settlements. The sophisticated architecture of Greek and Roman colonies in the Black Sea region in 500 B.C.E. –100 C.E. influenced Scythian house building. The architecture of later Slavic tribes was mostly wooden: log houses in forested highlands and frame houses in the forest-steppe. The Kyivan Rus urban centers resembled those of medieval Europe: a prince's fortified palace surrounded by the houses of the townsfolk. Tradesmen and merchants lived in suburbs called posad . Stone as a building material became widespread in public buildings from the tenth century, and traditions of Byzantine church architecture—cross plan and domes—combined with local features. Prime examples of this period are the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv (about 1030s) and the Holy Trinity Church over the Gate of the Pechersk Monastery (1106–1108). Elements of Romanesque style, half-columns and arches, appear in Kyivan Rus church architecture from the twelfth century, principally in the Saint. Cyril Church in Kyiv (middle-twelfth century), the Cathedral of the Dormition in Kaniv, and the Saint Elias Church in Chernihiv.

Ukrainian architecture readily adopted the Renaissance style exemplified by the Khotyn and Kamyanets'-Podil'skyi castles, built in the fourteenth century, Oles'ko and Ostroh castles of the fifteenth century, and most buildings in Lviv's Market Square. Many Ukrainian cities were ruled by the Magdeburg Law of municipal self-rule. This is reflected in their layout: Lviv and Kamyanets' Podil'skyi center on a city hall/market square ensemble.

Ukrainian baroque architecture was representative of the lifestyle of the kozak aristocracy. At that time most medieval churches were redesigned to include a richer exterior and interior ornamentation and multilevel domes. The most impressive exponents of this period are the bell tower of the Pechersk Monastery and the Mariinsky Palace in Kyiv, Saint George's Cathedral in Lviv, and the Pochaiv Monastery. A unique example of baroque wooden architecture is the eighteenth century Trinity Cathedral in former Samara, built for Zaporozhian kozaks. The neoclassical park and palace ensemble became popular with the landed gentry in the late eighteenth century. Representative samples are the Sofiivka Palace in Kamianka, the Kachanivka Palace near Chernihiv, and the palace in Korsun'-Shevchenkivskyi.

Ukrainian folk architecture of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries shows a considerable influence of baroque ornamentation and neoclassic orders while preserving traditional materials like wood and wattled clay. Village planning remained traditional, centered around a church, community buildings, and marketplace. The streets followed property lines and land contours. Village neighborhoods were named for extended families, clans, or diverse trades and crafts. This toponymy, dating from medieval times, reappeared spontaneously in southern and eastern Ukrainian towns and cities, such as Kherson, Mykolaiv, and Simferopol that were built in the eighteenth century.

Throughout the nineteenth century and into the beginning of the twentieth century, the empire architectural style came to Ukraine from the West. Modern urban planning—a grid with squares and promenades—was applied to new cities. At the beginning of twentieth century, there was a revival of national styles in architecture. A national modernism combined elements of folk architecture with new European styles. A prime exponent of this style is Vasyl' Krychevs'kyi's design of the 1909 Poltava Zemstvo Building.

Soviet architecture initially favored constructivism as shown in the administrative center of Kharkiv and then adopted a heavy neoclassicism pejoratively called totalitarian style for major urban centers. Post-World War II architecture focused on monobloc projects reflecting a collectivist ideology. However, contemporary Ukrainians prefer single houses to apartment blocs. The traditional Ukrainian house has a private space between the street and the house, usually with a garden. Striving for more private space people in apartment buildings partition original long hallways into smaller spaces. Dachas (summer cottages) are a vital part of contemporary Ukrainian life. Laid out on a grid, dacha cooperatives provide summer rural communities for city dwellers.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Ukrainians prefer to eat at home, leaving restaurants for special occasions. Meal times are from 7:00 to 10:00 A.M. for breakfast, from 12:00 noon to 3:00 P.M. for dinner or lunch, and from 5:00 to 8:00 P.M. for supper. The main meal of the day is dinner, including soup and meat, fowl, or a fish dish with a salad. Ukrainians

The Opera and Ballet Theatre in Odessa uses the half-columns and arches common to the Romanesque style of architecture.

generally avoid exotic meats and spices. A variety of soups—called borshch collectively—is traditional and symbolic, so it is never called "soup."

Menu items in restaurants are usually Eastern European. Expensive restaurants are patronized at supper time by a new breed of business executives who combine dining with professional interaction.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Culinary traditions in Ukraine are connected with ancient rituals. The calendar cycle of religious holidays combined with folk traditions requires a variety of specific foods. Christmas Eve supper consists of 12 meatless dishes, including borshch , cabbage rolls, varenyky (known in North America as pierogi), fish, mushrooms, various vegetables, and a wheat grain, honey, poppyseed, and raisin dish called kutya . The latter dish is served only at Christmas time. On Easter Sunday food that has been blessed previously is eaten after Resurrection services. It includes a sweet bread called paska , colored eggs, butter, meat, sausages, bacon, horseradish, and garlic. On the holiday of the Transfiguration (19 August), apples and honey are blessed and eaten along with other fruits of the season. Various alcoholic drinks complement the meals. It is customary to offer a drink to guests, who must not refuse it except for health or religious reasons.

Basic Economy. Traditional Ukrainian food products are domestic. Pressured by the economic crisis, people grow products in their home gardens and dachas. City and village markets are places of bartering consumer goods and food products. In the late 1990s, the development of the food industry was stimulated by economic reforms.

Land Tenure and Property. Private property rights were reinstated in Ukraine after 1991. Collective farms were abolished in 2000, and peasants received land titles. Privatization also has been successful in cities. Inheritance law in Ukraine, as in other countries, applies to transfers of property according to legal testaments.

Commercial Activities. The current government has decontrolled prices, reduced subsidies to factories, and abolished central economic planning. Ukraine imports chemicals, specialized metals, raw rubber, metalworking equipment, cars, trucks, electrical and electronic products, wood products, textiles, medicines, and small appliances. Ukraine exports aircrafts, ships, and agricultural and food products.

Major Industries. Heavy industry in Ukraine includes aircraft plants in Kharkiv; shipbuilding in Kherson, Mykolaiv, and Kerch; and steel and pig iron mills in Donetsk, Luhansk, and Zaporizhya oblasts. The latter depend on large supplies of coal and iron ore from Kryvbas and Donbas. Electronics, machine tools, and buses are produced in Lviv, and one of the world's largest agrochemical plants is located in Kalush. Other important industrial products include ferro-alloys, nonferrous metals, and building materials. Under the Soviet command economy, Ukraine's industry focused on raw materials and on the production of armaments and heavy machinery—25 percent of all Soviet military goods. Lately, successful joint ventures with foreign partners produce consumer goods. Seventy percent of the land is in agricultural use.

Trade. The integration of Ukraine into the world economic system is indispensable for an effective export-oriented economic reform and for foreign investments. Establishing trade relations with the G7 countries (the seven largest industrialized countries: United States, Japan, Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and Canada) is a priority for Ukraine's international economic strategy.

Division of Labor. Contemporary Ukraine has a high level of both official and hidden unemployment, especially in industry and in research institutions formerly oriented to military needs. Equal opportunity employment rules have not been implemented at the end of the twentieth century.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. Soviet Ukrainian society was officially classless with three equal groups: workers, peasants, and working intelligentsia. In reality the Communist Party elite enjoyed an immensely preferential status, with several internal gradations. In contemporary Ukraine many former Soviet bureaucrats ( nomenklarura ) retained their status and influence as members of the new administration or as newly rich business professionals. Education, health care, and research professionals, all dependent on state budgets, are in the lowest income bracket. Unemployment among blue-collar workers rose when heavy industry shifted its production focus. Farmers are in a transitionary phase in the re-institution of land property rights.

Symbols of Social Stratification. In Soviet times ownership of so-called deficit goods (scarce items available only to party elite in restricted stores) conferred a superior social status. The free market made prestigious goods available to anyone with cash. Social distinctions are popularly based on material status symbols such as cars, houses, luxury items, and fashionable attire. A more modest and traditional social and regional identification shows through apparel: many older suburban and country women wear typical kerchiefs, and Carpathian highlanders of any gender and age often wear characteristic sheepskin vests or sleeveless jackets.

Political Life

Government. Constitutionally, Ukraine is a democratic, social, law-based republic. The people exercise power through elected state and local governments. The right to amend the constitution belongs solely to the people and may be exercised only through popular referenda.

The office of president was instituted in 1917 in the Ukrainian National Republic and reinstated in 1991. The constitution vests executive power on the president and the prime minister and legislative power on the Verkhovna Rada , a unicameral body of

Farm workers travel in a village near Orane. Seventy percent of the land in the Ukraine is used for agriculture.

450 directly elected representatives. All suffrage is universal. The president is elected by direct vote for a five years' cadence. The president appoints the prime minister and cabinet members, subject to approval by the Verkhovna Rada .

Leadership and Political Officials. Ukraine has more than one hundred registered political parties. Right of center and nationalist parties include the National Front, Rukh, and UNA (Ukrainian National Association). The most prominent of them is Rukh, championing an inclusive national state and free market reforms. The leftist parties are the Communist, Progressive Socialist, Socialist, and United Socialist. Communists oppose land privatization and propose to revive the Soviet Union. Centrists are most numerous and include the Agrarian, Popular Democratic, Hromada, Greens, and Labor-Liberal parties. The Green Party became a political force because of its pro-active concern with ecology.

Political leaders and activists in Ukraine are generally accessible. However, most of them are used to old Soviet models of interaction. By contrast, younger politicians are much more attuned to a democratic style of communication.

Social Problems and Control. The Security Service of Ukraine, the Internal Affairs Ministry, and the Defense Ministry are responsible for national security, reporting to the president through his cabinet. The armed and security forces are controlled by civilian authorities. The Internal Affairs Ministry and its police, called militsia, deal with domestic crime and run correctional institutions. The Security Service succeeded the Soviet KGB. It deals with espionage and economic crimes. Public confidence in the authorities is gradually replacing the well-founded fear and mistrust of Soviet times.

Military Activity. The Ukrainian army conscripts males between the ages of eighteen and twenty five for eighteen months of compulsory service, with medical and hardship exemptions and student deferments. In 1992 the Ukrainian armed forces numbered 230,000. The Soviet Black Sea Fleet was incorporated into the Ukrainian naval forces. Ukrainian infantry participated in the United Nations peacekeeping effort in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Ukrainian armed forces conduct frequent joint maneuvers with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

Ukrainian social welfare programs are in their beginnings. Unemployment assistance is available at governmental centers that offer professional retraining aided by nongovernmental organizations. International charity organizations provide assistance to the needy. Help to Chernobyl disaster victims is funded by taxes and by international charity. Statistics from 1995 show Chernobyl-accident compensations to 1.5 million persons, 662,000 of them children.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

Community associations have a long history in Ukraine. The Prosvita (Enlightenment) Society established in 1868 under the Austrian Empire and in 1905 under the Russian Empire promoted literacy in Ukrainian through reading rooms and lending libraries, publishing activities, amateur theatrics, and other cultural activities. It was closed by the Soviets but flourished in western Ukraine until 1939. Prosvita was re-established in independent Ukraine with its original mission. Many contemporary Ukrainian non-governmental organizations derive from the human rights movements of the 1970s. A society, Memorial, was organized in the late 1980s to collect evidence and memories of political persecution and to assist former political prisoners.

The Ukrainian Women's Association was established in 1884. Currently, this organization and its diasporan counterpart concentrate on the preservation of national culture, on education, on human issues, and on charity work. Ukrainian women participate in politics through the Ukrainian Women Voter organization. The nongovernmental organization, La Strada , supports services for victims of sexual trafficking and helps to run prevention centers in Donets'k, Lviv, and Dnipropetrovs'k.

Gender Roles and Status

Division of Labor by Gender. Ukrainian labor laws guarantee gender equality, but their implementation is imperfect. Few women work at higher levels of government and management, and those who do are generally in subordinate positions. As in the Soviet Union, women work in heavy blue-collar jobs, except for coal mining. Nevertheless, there still is a traditional labor division by gender: teachers and nurses are mostly women; school administrators and physicians are mostly men. Women in typically female jobs such as teachers and nurses are paid less and promoted more slowly than men.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Males in positions of authority generally perceive women as the weaker sex. Women are welcome as secretaries or subordinates but not as colleagues or competitors. Women politicians and business executives are rare. They have to adopt a male style of interaction to function effectively. Sexual harassment in the workplace is widespread.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Ukrainians favor endogamy. Traditionally, young people chose mates at social events. Historically, parental approval and blessing were sought. Marriages against parents' wishes were rare in the past, and matchmakers mediated between the two families. The parents' role in the marriage has been preserved in contemporary Ukrainian culture through their responsibilities to organize and finance the wedding ceremonies and festivities for their children. The festivities show the family's social status. Most marriage ceremonies today are both civil and religious.

In traditional society public opinion pressured young people to marry early. This still leads to many marriages between the ages of seventeen and twenty five. It also leads to a high number of divorces, very rare in the traditional past. The Ukrainian Catholic Church prohibits divorce and the Ukrainian Orthodox Church discourages it. Civil courts grant divorce, adjudicating property and custodial rights.

Domestic Unit. The traditional Ukrainian domestic unit is a single family. Elderly parents eventually lived with the child who inherited their property. The chronic housing shortage in the Soviet Union and the economic crisis in contemporary Ukraine forced young couples to live with their parents in close quarters. This reduction of personal space frequently caused familial dysfunction.

The Ukrainian agricultural tradition clearly defined men's and women's parallel responsibilities. Men were responsible for tilling the fields and for their sons' socialization. Women were housekeepers, who also took responsibility for home crafts and budgets and for the daughters' socialization.

Inheritance. Ukrainian customs and laws of property inheritance never discriminated by gender. Historically, sons and daughters inherited parents' property equally, and a widow was the principal heir of her deceased husband. At present, inheritance is granted by testament. Without a testament, an estate is divided regardless of gender between children or close relatives in court. Inheritances and

Traders sell food at a Sunday market in Kiev. A marketplace is the centerpiece of almost every town and village.

deeded gifts are not subject to division in divorce cases.

Kin Groups. In Ukraine kinship beyond the immediate family has no legal standing, but it is an important aspect of popular culture. A kin group usually includes cognates of all degrees and godparents. A non-relative who is chosen as a godparent is thereby included into the kin group. Kin group reunions take place on family occasions such as marriages, baptisms, or funerals, and on traditional festive days.

Socialization

Infant Care. In 1992, 63 percent of children under age seven in urban areas and 34 percent in rural areas attended day care. These figures have decreased as current legislation provides paid maternity leaves for up to one year and unpaid leaves up to three years, recognizing Ukrainian women's preference for personal care of their children. Grandparents also provide care for grandchildren, especially in lower-income families. A well-cared for child is a traditional source of family pride. The decreasing number of births may be explained by the potential parents' inability to provide appropriate care for their children during economic crisis. An increasing number of children are abandoned by dysfunctional parents.

Child Rearing and Education. Ancient beliefs regarding child rearing still exist in contemporary Ukraine: a baby's hair is not cut until the first birthday; baptism is seen as a safeguard, and safety pins inside a child's clothing ward off evil spells.

Children attend school from age six. Education is compulsory and universal through nine grades. Students may graduate after the ninth grade at age sixteen and may work with special permission or enter vocational and technical schools. Since the number of specializations in these schools has decreased, most students finish the full eleven grades. A curricular revision is introducing new courses and programs for gifted children.

Higher Education. In post-secondary education undergraduate degrees are granted directly by universities. Candidate and doctor of sciences or arts degrees are granted by the Highest Attestation Commission of the Ministry of Education in a bureaucratically complicated system. Every major field of learning is covered in major universities. Every large and medium-sized urban center has at least one institution of higher learning.

Men talking in a hayfield near Rovno. Workers can now own land again, as collective farms were abolished in 2000.

Etiquette

Social interaction in Ukraine is regulated by etiquette similar to the rest of Europe. Some local idiosyncrasies are a personal space of less than an arm's length in business conversations and the habit of drinking alcohol at business meetings, a relic of Soviet times.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Religious beliefs are central to Ukrainian culture. Ukraine experienced a revival of many religions: Ukrainian Orthodox, Ukrainian Catholic, Protestantism, Judaism—including Hasidism—and Islam. The constitution and the 1991 Law on Freedom of Conscience and Religion provide for separation of church and state and the right to practice the religion of one's choice.

Religious Practitioners. Ukrainian Orthodox clergy are educated in divinity schools such as the Kyiv Theological Academy. The Ukrainian Catholic Church, banned in Soviet times, needs priests and provides a wide array of educational programs at the Lviv Theological Seminary. Protestant denominations, principally Baptists and Seventh-Day Adventists, train their ministers with the assistance of American and Western European mission programs. The numerically small Roman Catholic clergy is assisted by pastoral visitors from abroad. Since the time of independence, Jewish rabbis have been completing their studies in Israel. Muslim clergy is educated in Central Asia and Turkey.

Rituals and Holy Places. Ukrainian Orthodox and Catholic Churches share historic, ritual, and national heritages. Popular culture incorporated many ancient pagan rituals into a folk version of Christianity. Orthodox priests still perform exorcisms by the canon of Saint Basil the Great. The Holy Virgin icon and the spring of the Pochaiv Orthodox Monastery are believed to have miraculous healing powers. Zarvanytsia in western Ukraine is a place of holy pilgrimage for Ukrainian Catholics. The grave of the founding rabbi of Hassidism, situated near Uman', is a pilgrimage site for Hasidic Jews.

Death and the Afterlife. Ukrainians observe ancient funeral traditions very faithfully. A collective repast follows funeral services and is repeated on the ninth and fortieth days and then again at six and twelve months. An annual remembrance day called Provody on the Sunday after Easter gathers families at ancestral graves to see off once again the souls of the departed. Provody is widely observed in contemporary Ukraine. Under the Soviets it symbolized an ancient tradition. Its Christian symbolism represents Christ's victory over death. Its pre-Christian roots are attuned to the rebirth of nature in the spring and to an ancient ancestors' cult.

Medicine and Health Care

Ukraine's comprehensive and free health care includes primary and specialized hospitals and research institutions. Yet folk healing is not ignored by professional medicine. The popularity of folk healing is based on a distrust of standard medicine. The folk healers' knowledge of natural resources and lore is an ancient cultural heritage. Rituals, prayers, and charms are used by folk healers only as additional elements of healing. These healers prefer to work individually and let the patient determine the fee.

Another type of healer has become popular since the last days of the Soviet Union. These healers hold collective sessions eliciting mass hysteria from their audiences for an admission fee. Their popularity may be explained as a reaction among the less educated to stressful economic and social situations combined with the spiritual vacuum created by seventy-four years of compulsory atheism.

Secular Celebrations

There are several secular official holidays in Ukraine, some left over from Soviet times. The International Women's Day, 8 March, is celebrated now in the same context as Mother's Day: men present small gifts and flowers to all women family members and work colleagues. Victory Day, 9 May, became a day of remembrance of those who died in World War II. Constitution Day is 28 June. Independence Day, 24 August, is celebrated with military parades and fireworks.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. The former Soviet Union provided governmental support for the arts through professional organizations such as unions of writers, artists, or composers. These organizations still exist and try to function despite a general lack of funds. Young and unconventional artists usually organize informal groups funded by individual sponsors and grants from international foundations.

Literature. Ukrainian literature begins with the chronicles of Kyivan Rus and the twelfth century epic The Tale of Ihor's Campaign. Principal authors in

A Western Orthodox church in the Carpathian Mountains. Crosses and domes are common on Ukrainian churches.

the baroque period were Lazar Baranovych (1620–1693), Ioannykii Galyatovs'kyi (d. 1688), Ivan Velychkovs'kyi (d. 1707), and Dymitrii Tuptalo (1651–1709), who wrote didactic poetry and drama. Kozak chronicles of the early eighteenth century include The Chronicle of the Eyewitness, The Chronicle of Hryhorii Hrabyanka , and The Chronicle of Samijlo Velychko .

Ivan Kotlyarevskyi (1769–1838) first used the proto-modern Ukrainian literary language in his 1798 poem Eneida (Aeneid). He travestied Virgil, remaking the original Trojans into Ukrainian kozaks and the destruction of Troy into the abolition of the hetmanate. Hryhorij Kvitka Osnov'yanenko (1778–1843) developed a new narrative style in prose.

In 1837 three Galician writers known as the Rus'ka Trijtsia (Ruthenian Trinity)—Markiian Shashkevych (1811–1843), Ivan Vahylevych (1811–1866) and Yakiv Holovats'kyi (1814–1888)—published a literary collection under the title Rusalka Dnistrovaya (The Nymph of Dnister). This endeavor focused on folklore and history and began to unify the Ukrainian literary language. The literary genius of Taras Shevchenko (1814–1861) completed the development of romantic literature and its national spirit. His 1840 collection of poems Kobzar and other poetic works became symbols of Ukrainian national identity for all Ukrainians from gentry to peasants. In his poetry he appears as the son of the downtrodden Mother-Ukraine. Later, his own image was identified with an archetypal Great Father, embodying the nation's spirit. This process completed the creation of a system of symbolic representations in Ukrainian national identity.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Ukrainian writers under the Russian Empire—Panteleimon Kulish (1819–1897), Marko Vovchok (1834–1907), Ivan Nechuj-Levyts'kyj (1838–1918), Panas Myrnyj (1849–1920), and Borys Hrinchenko (1863–1910)—developed a realistic style in their novels and short stories. Osyp-Yurij Fed'kovych (1834–1888) pioneered Ukrainian literature in the westernmost Bukovyna under Austrian rule. Ivan Franko (1856–1916) is a landmark figure in Ukrainian literature comparable to Shevchenko. His poetry ranged from the most intimate introspection to epic grandeur. His prose was attuned to contemporary European styles, especially naturalism, and his poetry ranged from introspective to philosophical.

Mykhailo Kotsubynskyi (1864–1913); Vasyl Stefanyk (1871–1936), a master of short psychological stories in dialect; and Olha Kobylianska (1865–1942) all wrote in a psychologically true style. Lesya Ukrainka (1871–1913) saw Ukrainian history and society within a universal and emotionally heightened context in her neo-romantic poems like Davnya Kazka ( The Ancient Tale, 1894) or Vila-Posestra ( Sister Vila, 1911) and such dramas as U Pushchi ( In the Wilderness, 1910), Boiarynia ( The Noblewoman, 1910) and Lisova Pisnya ( Song of the Forest, 1910). Popularly, Shevchenko, Franko, and Lesia Ukrainka are known in Ukrainian culture as the Prophet or Bard, the Stonecutter, and the Daughter of Prometheus, images based on their respective works.

After the Soviet takeover of Ukraine, many Ukrainian writers chose exile. This allowed them to write with a freedom that would have been impossible under the Soviets. Most prominent among them were Yurii Lypa (1900–1944), Olena Teliha (1907–1942), Evhen Malaniuk (1897–1968) and Oksana Liaturyns'ka (1902–1970). Their works are distinguished by an elegant command of form and depth of expression along with a commitment to their enslaved nation.

Ukrainian literature showed achievements within a wide stylistic spectrum in the brief period of Ukrainization under the Soviets. Modernism, avant-garde, and neoclassicism, flourished in opposition to the so-called proletarian literature. Futurism was represented by Mykhailo Semenko (1892–1939). Mykola Zerov (1890–1941), Maksym Rylskyj (1895–1964), and Mykhailo Draj-Khmara (1889–1938) were neoclassicists. The group VAPLITE (Vil'na Academia Proletars'koi Literatury [Free Academy of Proletarian Literature], 1925–1928) included the poets Pavlo Tychyna (1891–1967) and Mike Johansen (1895–1937), the novelists Yurij Yanovs'kyi (1902–1954) and Valerian Pidmohyl'nyi (1901–1937?), and the dramatist Mykola Kulish (1892–1937). The VAPLITE leader Mykola Khvyliovyi (1893–1933) advocated a cultural and political orientation towards Europe and away from Moscow. VAPLITE championed national interests within a Communist ideology and therefore came under political attack and harsh persecution by the pro-Russian Communists. Khvyliovyi committed suicide after witnessing the 1933 famine. Most VAPLITE members were arrested and killed in Stalin's prisons.

From the 1930s to the 1960s, the so-called social realistic style was officially mandated in Ukrainian Soviet literature. In 1960 to 1970 a new generation of writers rebelled against social realism and the official policy of Russification. Novels by Oles' Honchar (1918–1995), poetry by Lina Kostenko (1930–) and the dissident poets Vasyl' Stus (1938–1985) and Ihor Kalynets' (1938–) opened new horizons. Unfortunately, some of them paid for this with their freedom and Stus with his life.

Writers of 1980s and the 1990s sought new directions either in a philosophical rethinking of past and present Ukraine like Valerii Shevchuk (1939–) or in burlesque and irony like Yurii Andrukhovych (1960–). Contemporary culture, politics, and social issues are discussed in the periodicals Krytyka and Suchasnist' .

Graphic Arts. Ancient Greek and Roman paintings and Byzantine art modified by local taste were preserved in colonies in the Northern Black Sea region. The art of the Kyivan Rus began with icons on wooden panels in Byzantine style. Soon after the conversion to Christianity, monumental mosaics embellished churches, exemplified by the Oranta in Kyiv's Saint Sophia Cathedral. Frescoes on the interior walls and staircases complemented the mosaics. Frescoes of the period also were created for the Saint Cyril Church and Saint Michael Monastery in Kyiv.

Medieval manuscript illumination reached a high level of artistry and the first printed books retained these illuminations. Printing presses were established in Lviv and Ostrih in 1573, where the

Kiev University. Every large or medium-sized urban center has at least one university.

Ostrih Bible was published in 1581. In the seventeenth century Kyiv became a center of engraving. The baroque era secularized Ukrainian painting, popularizing portraiture even in religious painting: The icon Mary the Protectress, for example included a likeness of Bohdan Khmelnytsky. Kozak portraits of seventeenth and eighteenth centuries progressed from a post-Byzantine rigidity to a high baroque expressiveness.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, several Ukrainian artists worked in Saint Petersburg: Antin Losenko (1737–1773), Dmytro Levyts'kyi (1735–1825), Volodymyr Borovykovs'kyi (1757–1825), and Illia Repin (1844–1928). In 1844 Taras Shevchenko, a graduate of the Russian Academy of Arts, issued his lithography album Picturesque Ukraine . An ethnographic tradition of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is represented by Lev Zhemchuzhnikov (1928–1912) and Opanas Slastion (1855–1933).

Mykola Pymonenko (1862–1912) organized a painting school in Kyiv favoring a post-romantic style. National elements pervaded paintings of Serhii Vasylkyvs'kyi (1854–1917). Impressionism characterized the works of Vasyl (1872–1935) and Fedir Krychevs'ky (1879–1947). The highly individualistic and expressive post-romantics Ivan Trush (1869–1941) and Oleksa Novakivs'kyi (1872–1935) ushered western Ukrainian art into the twentieth century.

Yurii Narbut's graphics (1886–1920) combined Ukrainian baroque traditions with principles of modernism. Mykhailo Boichuk (1882–1939) and his disciples Ivan Padalka (1897–1938) and Vasyk Sedlyar (1889–1938) combined elements of Byzantine art with modern monumentalism. Anatol' Petryts'kyi (1895–1964), an individualistic expressionist, survived Stalinist persecution to remain a champion of creative freedom to the end of his life.

In Lviv of the 1930s Ukrainian artists worked in different modernist styles: Pavlo Kovzhun (1896–1939) was a symbolist and a constructivist. Several western Ukrainian artists between the two world wars—Sviatoslav Hordynsky, Volodymyr Lasovsky, Mykhailo Moroz, and Olena Kulchytska—studied in Paris, Vienna, Warsaw, and Cracow. Many artists, such as the neo-Byzantinist Petro Kholodnyi, Sr. (1876–1930) and the expressionist Mykola Butovych (1895–1962), left Soviet Ukraine for western Ukraine in the 1920s to avoid persecution. Old icons influenced Vasyl Diadyniuk (1900–1944) and Yaroslava Muzyka (1896–1973). Alexander Archipenko (1887–1966), the most prominent Ukrainian artist to emigrate to the West, attained international stature with paintings and sculptures that combined abstraction with expressionism. Akin to Grandma Moses are the folk painters Maria Pryimachenko (1908–) and Nykyfor Drevniak (1900–1968).

After World War II many Ukrainian artists immigrated into the United States and other Western countries. Jacques Hnizdovsky (1915–1985) achieved wide recognition in engraving and woodcuts. The highly stylized sculpture of Mykhailo Chereshniovsky showed a unique lyrical beauty. Edvard Kozak (1902–1998), a caricaturist in pre-World War II Lviv, became a cultural icon in the diaspora.

After Stalin's genocide of the 1930s, social realism (a didactic kind of cliched naturalism applied to all literary and artistic media) became the only style allowed in the Soviet Union. In the 1960s some young Ukrainian artists and poets, who also defended civil rights, rejected social realism. For some of them this proved tragic: the muralist Alla Hors'ka was assassinated, and the painter Opanas Zalyvakha was imprisoned in the Gulag for long years. During the 1980s, modernism and postmodernism appeared in Ukraine in spontaneous art movements and exhibitions. Post-modern rethinking infused the works of Valerii Skrypka and Bohdan Soroka. An identity search in the Ukrainian diaspora showed in the surrealistic works of Natalka Husar.

Performance Arts. Ukrainian folk music is highly idiosyncratic despite sharing significant formal elements with the music of neighboring cultures. Epic dumas —ancient melodies, especially those of seasonal rituals—are tonally related to medieval modes, Greek tetrachords, and Turkic embellishments. The major/minor tonal system appeared in the baroque period. Typical genres in Ukrainian folk music are solo singing; part singing groups; epic dumas sung by (frequently blind) bards who accompanied themselves on the bandura (a lute shaped psaltery); and dance music by troisty muzyky, an ensemble of fiddle, wind, and percussion including a hammered dulcimer. Traditional dances— kozachok, hopak, metelytsia, kolomyika, hutsulka, and arkan —differ by rhythmic figures, choreography, region, and sometimes by gender, but share a duple meter. Traditional folk instruments include the bandura, a variety of flutes, various fiddles and basses, drums and rattles, the bagpipe, the hurdy-gurdy, the Jew's harp, and the hammered dulcimer.

The medieval beginnings of professional music are both secular and sacred. The former was created by court bards and by skomorokhy (jongleurs). The latter was created by Greek and Bulgarian church musicians. Ukrainian medieval and Renaissance sacred a capella music was codified and notated in several Irmologions. The baroque composer and theoretician Mykola Dylets'kyi developed a polyphonic style that composers Maksym Berezovs'kyi (1745–1777), Dmytro Bortnians'kyi (1751–1825), and Artem Vedel (1767–1808) combined with eighteenth-century classicism. The first Ukrainian opera Zaporozhets za Dunayem (Zaporozhian beyond the Danube) was composed in 1863 by Semen Hulak-Artemovs'kyi (1813–1873). The Peremyshl School of western Ukraine was represented by Mykhailo Verbyts'kyi (1815–1870), Ivan Lavrivs'kyi (1822–1873), and Victor Matiuk (1852–1912). All three composed sacred music, choral and solo vocal works, and music for the theater.

A scion of ancient kozak aristocracy, Mykola Lysenko (1842–1912) is known as the Father of Ukrainian Music. A graduate of the Leipzig Conservatory, a pianist, and a musical ethnographer, Lysenko created a national school of composition that seamlessly integrated elements of Ukrainian folk music into a mainstream Western style. His works include a cyclic setting of Shevchenko's poetry; operas, including Taras Bulba; art songs and choral works; cantatas; piano pieces; and chamber music. His immediate disciples were Kyrylo Stetsenko (1883–1922) and Mykola Leontovych (1877–1919). Twentieth-century Ukrainian music is represented by the post-Romantics Borys Liatoshyns'kyi (1895–1968), Lev Revuts'kyi (1899–1977), Vasyl Barvins'kyi (1888–1963), Stanyslav Liudkevych (1879–1980), and Mykola Kolessa (1904–). Contemporary composers include Myroslav Skoryk, Lesia Dychko, and Volodymyr Huba.

Many Ukrainian performers have attained international stature: the soprano Solomia Krushelnyts'ka (1973–1952), the tenor Anatoliy Solovianenko (1931–1999), and the Ukrainian-American bass Paul Plishka (1941–).

The theater in Ukraine began with the folk show vertep and baroque intermedia performed at academies. The baroque style with its florid language and stock allegories lasted longer in Ukraine than in Western Europe. The eighteenth-century classicism featured sentimentalist plays presented by public, private, and serf theaters. Kotliarevs'ky's ballad opera Natalka-Poltavka ( Natalka from Poltava ) and the comedy Moskal'-Charivnyk ( The Sorcerer Soldier ) premiered in 1819 and began an ethnographically oriented Ukrainian theater. In 1864 the Rus'ka Besida (Ruthenian Club) in Lviv under Austria established a permanent Ukrainian theater, while in the Russian Empire Ukrainian plays were staged by amateurs until banned by the Ems Ukase . Despite this prohibition, Marko Kropyvnyts'kyi (1840–1910) staged Ukrainian plays in 1881 along with Mykhailo Staryts'kyi (1840–1904) and the Tobilevych brothers. The latter became known under their pen and stage names as the playwright Ivan Karpenko-Karyi (1845–1907) and the actors and directors Panas Saksahans'kyi (1859–1940) and Mykola Sadovs'kyi (1856–1933). They created an entire repertoire of historical and social plays. Sadovs'kyi's productions marked the beginning of Ukrainian cinema: Sakhnenko's studio in Katerynoslav filmed his theater productions in 1910.

From 1917 to 1922 numerous new theaters appeared in both Eastern and western Ukraine. The most prominent new figure in theater was Les' Kurbas, director of The Young Theatre in Kyiv and later of Berezil theater in Kharkiv. His innovative approach combined expressionism with traditions of ancient Greek and Ukrainian folk theaters and included an acting method based on theatrical synthesis, a psychologically reinterpreted gesture, and a rhythmically unified performance. The expressionist style was adopted in the cinema by the internationally recognized director Oleksandr Dovzhenko (1894–1956).

Berezil's leading dramatist Mykola Kulish (1892–1937) reflected in his plays the social and national conflicts in Soviet Ukraine and the appearance of a class that used revolution for personal purposes. In 1933–1934 Kurbas, Kulish, and many of their actors were arrested and later killed in Stalin's prisons. As in every other art, social realism became the only drama style, exemplified by the plays of the party hack Oleksander Korniichuk. In 1956 former members of The Young Theatre and Berezil formed The Ivan Franko Theatre in Kyiv, but without the innovative character of the former ensembles.

Some Berezil members who escaped from the Soviet Union during World War II brought Kurbas's style to western Ukraine. After World War II these and other Ukrainian actors found themselves in refugee camps in Western Europe and made theater an influential force for preservation of national culture and reconstitution of the refugees' identity after cultural shocks of war and displacement. Theaters led by Volodymyr Blavats'kyi (1900–1953) and former Berezil actor Josyp Hirniak continued their performances as professional companies in New York in the 1950s and 1960s.

New ideas appeared in Ukrainian cinema of the 1960s. Director Kira Muratova's work showed existentialist concepts. The impressionistic and ethnographically authentic Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1964) by Sergij Paradzhanov and Jurii Ilienko was a prize-winner at Cannes. Ilienko is now a leading Ukrainian film director and cinematographer of post-modern style.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

The present National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine succeeds its Soviet eponym. It is an umbrella for research institutes, specializing in all fields of sciences and humanities. Most institutes are funded by the state, and unfortunately their budgets were cut by 38 percent in the year 2000. The scientific institutes usually sign independent contracts to provide research for industry. At present they have developed their own small enterprises in order to finance otherwise unfunded projects. Institutes in humanities and social sciences survive through publication grants from independent foundations. The National Academy of Medical Sciences and the National Academy of Pedagogy are similar to the Academy of Sciences and are financed by the state. Other research institutes are sponsored by diverse industries combining general research with product-oriented work. University-based research groups obtain funds from the Ministry of Education on the basis of open competition. The Ministry of Science has a yearly competition for project awards for research institutes. The competition concept is indicative of the transition from a centralized budget to funding through merit grants.

Bibliography

Armstrong, John A. Ukrainian Nationalism, 1939–1945, 1955.

Asyeyev, Yu S. Dzherela. Mystetstvo Kyivs'koi Rusi, 1980.

Before the Storm: Soviet Ukrainian Fiction of the 1920s, 1986.

Bilets'kyi, P. O. Ukrainske mystetstvo druhoi polovyny XYII–XVIII stolit', 1981.

Chirovsky, Nicholas L. Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Ukraine, 1986.

Constitution of Ukraine, 1996.

Contemporary Ukraine: Dynamics of Post-Soviet Transformation, 1998.

Conquest, Robert. The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine, 1986.

von Hagen, Mark. "The Russian Imperial Army and the Ukrainian National Movement in 1917." The Ukrainian Quarterly , 54, (3–4): 220–256, 1998.

Hnizdovsky. Woodcuts, 1944–1975, 1976

Hordynsky, Sviatoslav. The Ukrainian Icon of the Twelfth to Eighteenth Centuries, 1973.

Hrushevs kyi, Mykhailo. History of Ukraine-Rus', 1997.

Iavornyts'kyi, D. I. Istoria zaporiz'kykh kozakiv, 1992.

——, M. C. Samokysh, and S. I. Vasyl'kivs'kyi. Z Ukrains'koi starovyny,

Ilnytzkyj, Oleh S. Ukrainian Futurism, 1914–1930: A Historical and Critical Study, 1997.

Isajiw, Wsevolod W., Yury Boshyk, and Roman Senkus, eds. The Refugee Experience: Ukrainian Displaced Persons after World War II, 1992.

Knysh, George D. Rus and Ukraine in Medieval Times, 1991.

Kolessa, F. M. Muzykoznavchi pratsi, 1970.

Krypiakevych, Ivan, ed., Istoria ukrains'koi kul'tury, 1994.

Kulish, Mykola. Zona/ Blight 1996.

Kultura i pobut naseleniia Ukrainy, 1991.

Kuzio, Taras. Ukraine under Kuchma: Political Reform, Economic Transformation, and Security in Independent Ukraine, 1997.

Lavrynenko, Yurii. Rozstriliane vidrodzhennia, 1959.

Luckyj, George S. N. Ukrainian Literature in the Twentieth Century: A Reader's Guide, 1992.

Lobanovs'kyj, B.B., and P.I. Hovdia. Ukrains'ke mystetstvo druhoi polovyny XIX–pochatku XX st., 1989.

Lohvyn, Hryhorii ed. Sophia Kyivs'ka. Derzhavnyj arkhitekturno istorychnyj zapovidnyk, 1971.

Magosci, Paul Robert. A History of Ukraine, 1996.

Maria Prymachenko, 1989.

Michaelsen, Katherine Janszky, and Nehama Guralnik, eds. Alexander Archipenko: A Centennial Tribute, 1986.

Motyl, Alexander J. Dilemmas of Independence: Ukraine after totalitarism, 1993.

Mudrak, Myroslava. The New Generation and Artistic Modernism in the Ukraine, 1986.

Natalka Husar's True Confessions, 1991.

Onyshkevych, Larissa M. L. Z. ed. Antolohia Modernoi ukrains'koi dramy, 1998.

Ovsijchuk, V. A. Ukrains'ke mystetstvo XIV-pershoi polovyny XVII stolittia, 1985.

Panibud'laska, V. F. ed. Natsional'ni protsesy v Ukraini. Istoria I suchasnist', 1997.

Reeder, Ellen, ed. Scythian Gold: Treasures from Ancient Ukraine, 1999.

Serech, Yury. Druha cherha. Literatura. Teatr. Ideolohii, 1978.

Sevcenko, Ihor. Ukraine Between East and West: Essays on Cultural History to the Early Eighteenth Century, 1996.

Shcherbak, Yurii. Chernobyl: A Documentary Story, 1989.

Shkandrij, Myroslav. Modernists, Marxists, and the Nation: Ukrainian Literary Discussion of the 1920s, 1992.

Sochor, Zenovia A. "No Middle Ground? On the Difficulties of Crafting a Political Consensus in Ukraine." Peoples, Nations, Identities: The Russian-Ukrainian Encounter. The Harriman Review 9 (1–2): 57-61.

Spirit of Ukraine: Five Hundred Years of Painting; Selections from the State Museum of Ukrainian Art, Kiev, 1991.

Subtelny, Orest. Ukraine: A History, 1988.

Szporluk, Roman. "Russians in Ukraine and Problems of Ukrainian Identity in the USSR." Ukraine in the Seventies, 1974.

Towards an Intellectual History of Ukraine: An Anthology of Ukrainian Thought from 1710 to 1995, 1996.

Ukrainian Painting, 1976.

Ukrains'kyi narodnyi odiah XVII-pochatku XIX st. v akvareliakh Yu.Hlohovs'koho, 1988.

Ukrains'kyi seredniovichnyj zhyvopys (Ukrainian Medieval Painting), 1976.

Voropaj, Oleksa. Zvychai nashoho narodu, 1958.

Vozniak, Mykhailo. Istoriia ukraïns koï literatury, 1992.

Wanner, Catherine. Burden of Dreams: History and Identity in Post-Soviet Ukraine, 1998.

Wolowyna, Oleh. "Ukrains'ka mova v Ukraini: Matirnia mova za natsional'nistiu I movoiu navchannia." Essays on Ukrainian Orthography and Language, 1997.