Culture of Tunisia

Culture Name

Tunisian

Alternative Names

Republic of Tunisia or Tunisian Republic. In Arabic the name of the capital, Tunis, includes the whole country. The old Roman province of Africa under the Arabs became first Ifriqiya, then later Tunisia.

Orientation

Identification. Originally Tunis was a satellite town of Carthage, located about 6.2 miles (10 kilometers) inland from the Mediterranean Sea. Carthage with its port was the historic urban center in the region from the ninth century B.C.E. through the eighth century C.E. Since Carthaginian times the rural hinterland around Carthage, later Tunis, has approximately corresponded to the contemporary boundaries of Tunisia. It has sometimes been part of a larger empire, as when it was the Roman province of Africa, sometimes an independent unit, as under the medieval Hafsid dynasty, but always distinct. Today Tunisia is part of the larger Arab world, with which it shares a language and many cultural elements, including a political identification. Within this broader identity, the sense of Tunisian uniqueness remains strong.

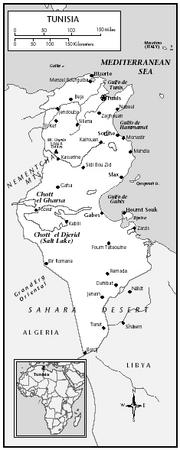

Location and Geography. Tunisia is located in north-central Africa, between Algeria and Libya, with an area of 63,200 square miles (164,000 square kilometers). It has a lengthy Mediterranean coast and is very open to Mediterranean influences. Tunisians are a maritime people and have always maintained extensive contacts by sea with other Mediterranean countries. The main cities are all on the coast, and contemporary development, including tourism, is also concentrated on the coast. Some ecologically significant wetlands are found along the coast. From a physical and economic point of view, there is considerable variety in the country, from cork oak forests in the north to open desert in the south, but this physical variety has not produced cultural variety.

Mountains play a role in Tunisia as determiners of climatic variation and refuge for political outsiders. A chain of mountains separates the grain-producing areas of northern Tunisia from the high, dry plateau to the south, where animal husbandry dominates, and the semiarid coastal plains where olive cultivation is common. The highest point is Mount Ash-Sha'nabi, near Al-Qasrayn (Kasserine), at 5,050 feet (1,544 meters). The country is heavily dependent on rainfall, which falls mostly between September and May, and in northern Tunisia averages around 20 inches (50 centimeters) a year. The mountains in the northwest attract heavier rain and even snow in the winter. The longest river in the country is the Medjerda, which rises in Algeria and flows through Tunisia to the sea. Many drainage systems end in saline lakes. Southern Tunisia extends into the Saharan desert, and includes some notable oases; people live wherever there is water.

Demography. In the 1994 census, Tunisia's population was 8,785,711. In 2000 the population was estimated at 9.6 million with a natural increase rate of 1.6 percent. The urban population is 64 percent and tending higher. About 19 percent of the population lives in Greater Tunis. The adult literacy rate is 69 percent (58 percent for women, 80 percent for men), and the life expectancy is 70 years (69 for men, 71 for women). The per capita gross domestic product (GDP) was $2,283 (U.S.) in 1998. The United Nations Development Program's report for 2000 placed Tunisia in the middle rung of development, ranking 101st out of 174 countries.

Almost all Tunisians are Arabic-speaking Muslims. Berber languages are spoken in a few villages in southern Tunisia, and there is a small remnant of the historic Jewish population, now concentrated in Tunis and on the island of Jerba off the southern

Tunisia

coast. Before the migration of Jews to Israel and France, most towns had a small Jewish community, and Tunis itself was 10–15 percent Jewish. Neither of these minorities now reaches 1 percent.

Linguistic Affiliation. The language of Tunisia is Arabic. As elsewhere, the spoken language differs considerably from the written language. The regional dialects are tending to disappear under pressure from mass media centered in Tunis. The main second language is French. The educational system is geared to produce bilingualism in French and Arabic, with a few elite schools now focusing on English. Only a minority of Tunisians, however, are comfortable in French. Fluency in French is a status marker, and so social considerations, as well as the practical ones of an opening to the world, have impeded full Arabization. Knowledge of other European languages is largely a function of television exposure and tourism.

Symbolism. Perhaps because Tunisia is a relatively small and homogeneous country, the sense of national identity is strong. It is constantly maintained by reference to recent national history, particularly the struggle against French colonialism (1881–1956) and the subsequent efforts to create a modern society. The struggle was more political and tactical than violent, though there were some violent outbursts. This narrative is constantly rehearsed, in the sequence of public holidays, in the names of streets, and in the subject matter of films and television shows. The sense of difference is also reinforced by the achievements of the national football (soccer) team in international competitions.

The Tunisian flag did not change during or after the colonial period. The flag has a red star and crescent, symbolizing Islam, in a white circle in a red field. It derives from the Ottoman flag, reflecting Ottoman suzerainty over Tunisia from the sixteenth through the nineteenth centuries.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. Tunisia's geographical location has meant that many different peoples have entered and dominated the country. Probably the original population was Berber speaking. The parade of invaders began with the Phoenicians, who settled Carthage, used it as a trading base, and eventually entered into a losing conflict with Rome. Under the Romans, who dominated Tunisia for several centuries, Christianity also entered the country. After the decline of the Romans, the Vandals invaded from the west, followed by a Byzantine reconquest from the east. The Byzantines were replaced by Muslim Arabs from the east, but by land, in the seventh century. Tunisia has been predominantly Arabic-speaking and Muslim since then, though dynasties have come and gone. After 1574, Tunisia was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire. The Spanish held parts of Tunisia briefly before the Ottomans, and the French ruled Tunisia during the colonial period from 1881 to 1956.

Tunisia was ruled by the Husseini dynasty of beys from 1705 to 1957. The beys of Tunis and their government tried to construct a modern Tunisia during the nineteenth century to fend off stronger European powers. After France took over Algeria in 1830, pressure on Tunisia grew. In 1881, the bey of Tunis accepted a French protectorate over the country. France set up a colonial administration, and facilitated the settlement in Tunisia of many French and other Europeans, mainly Italians. About a generation after the establishment of the protectorate, a nationalist movement emerged, seeking a modern and independent Tunisia. The Destour (Constitution) Party was founded about 1920, and in 1934 an offshoot known as the Neo-Destour Party became dominant under the leadership of Habib Bourguiba (1903–2000).

Parallel to the political movement, a strong labor movement also emerged. Usually working together, the political and labor wings struggled against French colonialism until independence in 1956. A republic was declared in 1957, with Bourguiba as the first president. The independent government carried out many social reforms in the country, with regard to education, women's status, and economic structures. During the 1960s the government followed a socialist policy, then reverted to liberalism while retaining a substantial state involvement. In 1987 Bourguiba was declared senile and replaced by Zine El Abidine Ben Ali (1936–), but without a major shift in policy. Contemporary policy is pragmatic rather than ideological.

National Identity. By the end of the nineteenth century, Tunisians distinguished between Moors, Turks, Jews, Berbers, Andalusians, Arabs, and various sorts of Europeans. Few of these distinctions are relevant today. Some groups were assimilated, others such as the colonial Europeans eventually retreated. None of the invasions and population movements left traces in the ethnic structure of the country. The geography of the city of Tunis and its hinterland, and the effort to create a national culture, have proved stronger than diverse ethnic origins in shaping Tunisian identity.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

Tunisia is dominated by its capital city, Tunis. The other main cities are along the coast, and include Bizerte, Sousse, Sfax, and Gabès. These precolonial towns have an older nucleus, or medina, surrounded by modern administrative and residential neighborhoods and by slums. The classical town in Tunisia includes a main mosque, a market, and a public bath. All three are sites for interaction. Friday prayers are essentially linked with urbanity, the market attracts people for trade and exchange, and the public bath expresses a certain concern with personal cleanliness from a time when houses did not have their own bathrooms. The cities are well supplied with water, electricity, and other public services. Garbage and sewage, formerly just dumped, are now treated and sometimes recycled.

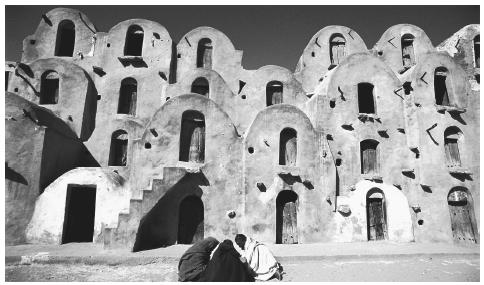

The old urban neighborhoods contain magnificent examples of traditional Islamic urban architecture, both public buildings such as mosques and markets as well as elite residences. Houses rich and poor are built around a courtyard, which serves as a family work space away from strange eyes. Entrances are designed to prevent passersby from seeing into the building. The older pedestrian neighborhoods are often not readily accessible to automobiles, while the newer suburbs are built with cars in mind. Generally, buildings in Tunisia are painted white with blue trim.

Some rural people live in villages, but away from the coast many live in scattered homesteads, near their fields. People seek privacy by distancing themselves from neighbors. Formerly, Tunisia had a substantial nomadic population, which lived in tents, but this is now exceptional. Water scarcity is a problem for Tunisia. The annual per capita availability of renewable water is low and puts Tunisia in the water-scarce category. Tunisia has managed to tap all its water resources and to provide for all urban areas and some rural areas, but the system is stretched to its limit. Rural people may have to haul water from a distance, and with considerable effort. City water is brought from distant mountains, since the coastal areas rely heavily on rainfall alone.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Traditional Tunisian cuisine reflects local agriculture. It stresses wheat, in the form of bread or couscous, olives and olive oil, meat (above all, mutton), fruit, and vegetables. Couscous (semolina wheat prepared with a stew of meat and vegetables) is the national dish, and most people eat

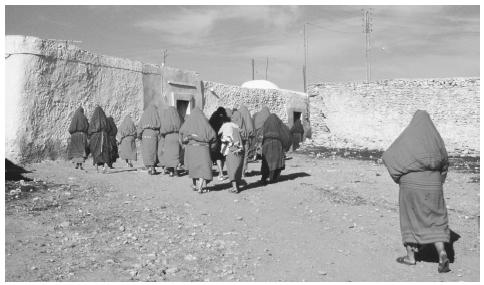

Tunisian mourners wear traditional bright red costumes at funerals. Corpses are laid on the left side, facing Mecca.

it daily in simple forms, and in more complex forms for celebrations. Bread with stew is a growing alternative. Tunisians near the coast eat a lot of seafood, and eggs are also common. Tunisians tend to eat in family groups at home, and restaurants are common in tourist areas and for travelers. In the countryside, tea is served in preference to the urban coffee. Tunisians also fast from dawn to dark during the month of Ramadan.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Sweet or colorful dishes symbolize religious holidays, usually in addition to couscous. For weddings and other happy occasions, sweets are added to the couscous. Animals are slaughtered for religious gatherings, and the meat is shared among the participants as a way of symbolizing the togetherness.

Basic Economy. Tunisia is historically an agricultural country, and agriculture now absorbs 22 percent of the labor force; about 20 percent of the country is farmland. Rain-fed agriculture dominates and concentrates on wheat, olives, and animal husbandry. Wheat is mostly used domestically, and Tunisia is a major world producer of olive oil. Animal husbandry for domestic consumption is significant, especially sheep and goats, but also cattle in the north and camels in the south. Citrus and other tree crops are produced both under rain-fed and irrigated conditions, and are often exported. About 6 percent of the arable land is irrigated and is used to grow the full range of crops, but perhaps is most typically used for vegetables and other garden crops. Dates are grown in irrigated oases. The long coastline orients Tunisians toward the sea and toward fishing.

Land Tenure and Property. Traditionally, much agricultural land and urban property was held as collective property, either undivided inheritances or endowed land. From the mid-nineteenth century this system has been giving way to the predominance of individual land and property ownership. The state itself is a major property owner.

Commercial Activities. Most aspects of life in Tunisia have been monetized, apart from some subsistence farming. Subsistence farmers can be recognized because they cultivate a variety of crops, while market-oriented farmers concentrate on a few. Most Tunisian farmers expect to sell their crops and buy their needs. The same applies to craftsmen and other occupations. Rural Tunisia is covered by an interlocking network of weekly markets that provide basic consumption goods to the rural population and serve as collecting points for animals and other produce. Among the very poor in Tunisia are self-employed street vendors, market traders, and others in the lower levels of the informal sector.

Major Industries. The national government after independence continued to develop phosphate and other mines, and to develop processing factories near the mines or along the coast. There is some oil in the far south and in the center. Efforts to develop heavy industry (such as steel and shipbuilding) are limited. More recently light industry has expanded in the clothing, household goods, food processing, and diamond-cutting sectors. Some of this is done in customs-free zones for export to Europe.

Considerable small-scale manufacturing is done in artisanal workshops for the local market. These workshops, often with fewer than ten workers including the owner, are the upper level of the informal sector. Overall, manufacturing accounts for 23 percent of the labor force.

The service sector is also substantial in Tunisia. Employment in services is about 55 percent of the labor force. A major service industry is tourism, mostly along the coast and oriented toward Europeans on beach holidays with excursions to historical sites. Contact with tourists has been a major source of new ideas. Banking and trade are also well developed, both internationally and in terms of a network of markets and traders in the country.

Trade. Exports include light industry products and agricultural products, such as wheat, citrus, and olive oil. Imports include a variety of consumer goods and machinery for industry.

Division of Labor. The national division of labor reflects education and gender. There are many relatively complex jobs, whether for the government or not, that require specific educational skills and background. Thus the educational system provides a major input into the division of labor.

Many Tunisian men, and some families, now live and work abroad. This began with migration to France in the early twentieth century. Tunisians now also migrate to various European countries, and to oil countries such as neighboring Libya or the more distant Persian Gulf nations. Remittances and other forms of investment at home are significant, and returned migrants play a role in many communities. Since many men from the marginal agricultural areas have migrated in search of work, agricultural labor has been feminized. Intellectual and professional Tunisians also migrate, but the paths are more individual.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. Tunisian society is marked by class distinctions, with considerable upward mobility and fuzzy class awareness. Class distinctions based on wealth are the most apparent, with enormous differences between the wealthy bourgeoisie living in the affluent suburbs of Tunis and the rural and urban poor. Wealth in one generation leads to improved education in the next. Status through ancestry is relatively unimportant.

Symbols of Social Stratification. The symbols of social stratification are basically in style and level of consumption.

Political Life

Government. Tunisia is a republic headed by a president. There is a prime minister, a council of ministers, and an elected national assembly. Local administration works through officials appointed by the minister of interior. Urban areas organized in municipalities also have a town council.

Leadership and Political Officials. The political party that took the lead in the nationalist movement from 1934 to 1956 has essentially been a single party since independence in 1956. This party was initially known as the Neo-Destour Party, then in the 1960s was called the Destour Socialist Party, and since the deposition of Bourguiba in 1987 is named the Democratic Constitutional Rally. The word that has remained in its name is "constitution" ( destour in Arabic), which implies a concern with legality. This party has historically been relatively well structured with active local branches organized in a rational hierarchy. There is a parallel structure for women. The formerly autonomous labor union movement has now essentially been coopted. Successful political careers involve slow advance in the party hierarchy.

Some opposition parties are allowed to operate legally, but have little influence. In the 1999 elections, the government introduced a form of proportional representation to allow opposition parties to enter parliament despite relatively low voting scores. The twenty-one women in parliament represent 11.5 percent of the membership.

Social Problems and Control. Crime is low, and public order is generally quite peaceful in Tunisia, though there have been one or two outbreaks of rioting around economic issues in different parts of the country. The concern of the government to maintain order is reflected in the growth of police

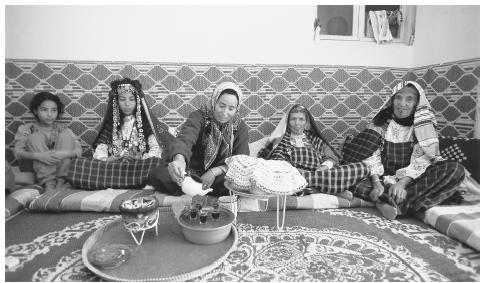

A bedouin family drink tea in Matmata. Tunisian families are patriarchal.

forces in recent years. Political dissidents of all kinds are given very little freedom to act. Even traffic police are severe.

Military Activity. Tunisia's relatively small army has seen little action.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

Part of the contract between government and people is that government officials take the lead in promoting welfare and development. These programs are done either with foreign bilateral assistance or through the government's own resources. They include programs in the areas of health, family planning, environment, agricultural and regional development, and major infrastructure construction, such as dams and irrigation projects.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

Since independence, the government has worked to create a sense of individual citizenship, with citizens dealing individually with the state. Thus in practice it restricts the activities of nongovernmental organizations. The more political organizations, such as human rights, women's rights, or environmental organizations, are either coopted or suppressed. The government and the party themselves offer a range of associations for women, youth, and labor, and it is difficult to compete. After independence, the labor union organization entered into a long struggle to maintain its independence of government control, but eventually succumbed. Efforts to create water user associations in rural areas were limited by laws restricting their right to collect and spend their own money. An important form of nongovernmental organization is the sports clubs, essentially football clubs, which are usually dominated by figures from the national elite.

Gender Roles and Statuses

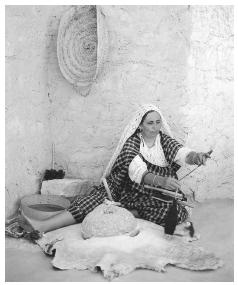

Division of Labor by Gender. In family and household settings, the men are responsible for producing an income, whether through self-employment in agriculture or through a job, while women are responsible for managing the household. In agricultural households, this may involve transforming the raw material of agriculture into useful items—spinning and weaving wool from family sheep, preparing the wheat into couscous, or preserving fruit and vegetables. Women work in agriculture either in a family context, especially when

The architecture in Ksar Ouled Soultane reflects the influence of Islamic design.

men are absent, or sometimes as wage labor on the large farms in northern Tunisia. Women who work for wages in agriculture are paid about half the rate for men. This rate is sometimes justified on the grounds that they do not produce as much, but this is also a strategy to maintain low overall wages. In the wider community, the division of labor is less strict, and there are many women who now occupy jobs in government, industry, and the private sector. In the late 1990s, women were 36 percent of professional and technical workers, and 13 percent of administrators and managers. Their per capita share of GDP, however, was about half the national average.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Independent Tunisia under Bourguiba made a major effort to improve women's status by encouraging education and employment, improving the conditions of marriage, and encouraging family planning. This has reduced rather than eliminated the gap between the status of women and men. Women still endure a lot of stress trying to follow a career or enter public life in a male-dominated society. Some men resent the formal employment of women when unemployment of educated men remains high, and also scorn the idea of women in public life.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Choice of marriage partners may be by arrangement between families or the result of individual selection based on acquaintances made at school or work. There is some preference for cousins, in part because cousins are considered to be of equal status. Girls are not supposed to marry beneath them. Mothers search for brides for their sons, and may scrutinize possible candidates during the women's periods in the public baths. Once an engagement is settled on there is a complex series of visits between the two families. Sometimes disputes over gifts or etiquette leads to a collapse of the engagement, or one or the other of the partners may back out. The marriage ceremony itself involves the shift of the bride from her house to her groom's house, while the groom waits outside, so that he may enter into the bridal chamber where she is waiting. After the consummation of the marriage, there is a period of seclusion until the young couple reenters society.

The legal aspects of marriage are covered by the Personal Status Code, introduced right after independence (1956) by Bourguiba. This code generally had the effect of protecting women's rights and encouraging companionate marriage. The code prohibited polygamous marriages and forced marriage for girls, established a minimum age for marriage, and required judicial divorce rather than repudiation. Later amendments allowed women to initiate divorce.

Domestic Unit. The household in Tunisia is based on the patriarchal family. Beliefs and practices sustain the notion of the dominant male head. Most households are based on the nuclear family. Apart from the urban poor in the old city of Tunis, most households at all income levels consist of a separate house, together with its courtyard and annexes. Within the household, tasks are assigned on the basis of age and gender, as well as personal skills. Changes in educational and employment patterns have made the companionate marriage between equals more common.

Inheritance. Inheritance, following Islam, is partible, with male heirs receiving twice the share of equivalent female heirs. Bequests are allowed only to those who would not otherwise inherit. Certain kinds of property, such as farmland, may not actually be divided in use, though a record of the inheritance situation is maintained. Formerly, property could be kept as a unit by making it endowed for the family, but this is now rare.

Kin Groups. Tunisians recognize the extension of kinship beyond the nuclear family, and maintain the network of connections. As elsewhere, these links are more alive among the wealthy and powerful, where the stakes are higher, and among the very poor, where they are a major resource.

Where a family retains a connection with an ancestral "saint," the annual festival of this saint serves as a family reunion, and sacralizes the group, meaning those descended in the male line from the ancestor. In the parts of interior Tunisia where pastoralism once dominated, these connections extend to a "tribe" (here called an arsh ) such as the Zlass around Al-Qayrawan (Kairouan) or the Freshish and Mateur around Al-Qasrayn and Sbetla. This is a larger identity based on extension of kin ties. These units and their chiefs were recognized in the colonial system, but were rejected by the independent government. The ties are now only occasionally activated, for instance in elections and marriages.

Socialization

Infant Care. Infants are cared for by their mothers or older siblings in a family setting. Most newborns are breastfed.

Child Rearing and Education. Once children can walk, their fathers may play more of a role in their

Women's responsibilities can include spinning and weaving wool.

upbringing, especially for boys. At age six, the state takes over socialization for both boys and girls through virtually universal primary school. The schools are well-organized and managed, though perhaps underequipped.

Higher Education. The paths of children begin to diverge after primary school. Some remain on an academic track, while others undertake vocational education. Child labor is relatively uncommon, but boys may begin to work as apprentices when they are teenagers. Those who remain on an academic track eventually pass a "baccalaureate" type of examination, which governs their subsequent career. The academic elite continue on to one of the university faculties in Tunis or elsewhere.

Etiquette

Tunisians are relatively egalitarian in their interpersonal relations, but there is a strong sense of etiquette. People should be addressed respectfully. A man should not show too much curiosity towards the women in his friend's family, and may not even know their names. In some cases, men do not visit each other's homes because the women would inevitably be present. Some people with a sense of their own status do not visit those they consider lower in rank. These rules are relaxed in the urbanized upper classes.

Modesty codes for women prevail in some areas. In traditional urban society, women were supposed to be circumspect in their behavior. They were supposed to limit trips outside the house to certain culturally approved destinations, such as the public bath or the tombs of their relatives in the cemetery. In certain sectors of Tunisian urban society, women cover head and body in public with a rectangular white cloth, the safsari. Rural women follow different dress practices, but may adopt urban forms on visits to the city. These older practices are rarer now, and the "modern" veil has been officially discouraged, so there is no common dress code.

Men are also supposed to show respect for each other. A man is not supposed to smoke in front of his father, and he is not supposed to carry his own child in the presence of his father. Brothers might frequent different cafs so that the presence of a brother would not inhibit relaxation. Traditional male dress included loose trousers and shirt, with perhaps a robe over that, and a red-felt skullcap. Again, practices are now less uniform than in the past, with the differences reflecting degrees of modernity, or level of education and income.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. As Muslims, Tunisians accept the oneness of God and the power of his word as expressed in the Koran. For many purposes, people refer to the texts of the Koran and of certain related texts such as the Hadith (authentic traditions). The Shari'ah, or Islamic law, is central to people's understanding of what is proper. Together these texts lay down correct behavior and lead to certain everyday rituals. In practice there is a certain amount of variation in belief and practice. The variation corresponds broadly to the social position of families and individuals.

The religious calendar provides the main occasions for the expression of these beliefs. The five daily prayers, the weekly cycle organized around the Friday midday prayer, and the yearly festivals structure time. The annual cycle includes the fasting month of Ramadan. There is also the Feast of the Sacrifice, which coincides with the annual pilgrimage to the holy places of Mecca and Medina. On this feast, every householder must sacrifice a ram in emulation of Abraham's willingness to express his faith by sacrificing his son, who was then miraculously replaced on the altar by a ram. Another festival, traditionally more associated with sufi orders, is the Prophet's Birthday. The feast of Ashura, commemorating the martyrdom of the grandson of the prophet Muhammad at the battle of Kerbala, may be celebrated in Tunisia by visits to tombs and bonfires. The dates of these celebrations are all set according to the Islamic lunar calendar, which does not follow the seasons.

Religious Practitioners. Islam does not recognize a sacerdotal priesthood. The formal religious specialists are experts in Islamic law and practice, including religious judges, prayer leaders and others who care for mosques, and traditional teachers of Arabic and religious texts. These posts are limited to men. Informal religious specialists also include men (and sometimes women) who are seen as the vessels of divine grace ( baraka ) and who thus have the power to heal, foresee the future, interpret dreams, or mediate with God on behalf of petitioners. This divine grace may be attributed because of the individual's actions or it may be inherited. Between the formal and the informal are the leaders of Sufi orders. Since the 1970s a reform movement has grown up in Tunisia. This movement is based on a close adherence to the Koran and other sacred texts, and is opposed to some of the heterodox practices described below. It also has political implications, and at times functions as an opposition party. Thus its prominent leaders are more political than religious. Most are now in exile or prison.

Rituals and Holy Places. The main life-crisis rites are ritualized through Islam—birth, naming, circumcision (for boys), marriage, pilgrimage, and death. Muslims are enjoined to make the pilgrimage to the holy places of Mecca and Medina, located in Saudi Arabia. For Tunisians, as for most Muslims, the holy places are a "center out there." Both the departure on pilgrimage and the return are ceremonialized by visits to mosques, family gatherings, and gifts. Of course, the stay in the holy places is also part of this rite of passage. To reflect the new status, a returned pilgrim should be addressed as "hajj," meaning pilgrim.

Tunisia is also a land of wonder as expressed in the numerous holy places scattered in rural and urban areas. These shrines in principle contain the tomb of a holy person, often male, and serve as key points for links between the human and the divine. Some shrines are the object of an annual festival that draws together people from a particular community (such as a village, extended family, or tribe) to honor the saint. These festivals intensify and reinforce the solidarity of that group. Each town or community is likely to have one shrine that serves as the symbolic focal point for that group. People make individual visits to a shrine for many other reasons, including a specific request for help from the shrine's "saint," or to thank the saint for favors granted. Thanking the saint may turn into an annual ritual of reconnection between the individual and the saint, and through the saint with God. Properly, only God can grant favors, and the saint is merely the intermediary, but there is some slippage toward the idea of the power of the saint to help directly.

An examination of these shrines shows that many reflect unusual features in the landscape, such as caves, hilltops, springs, unusual trees, or points on the coastline. Presumably this saint cult incorporates certain features of an older nature cult.

Some people believe that saints, those connected with spirits or jinns, may also be angry if they feel slighted, because, for instance, people overlooked an annual visit of reconnection. Thus they send their jinns to afflict those who slight them. Cure for the affliction consists of diagnosing the source and placating the saint so that the affliction is reversed. The curing usually also involves a reaffirmation of family ties, since it is effective only if it takes place in a group context. Although heterodox in Islamic terms, this complex serves as a folk explanation for illness or misfortune. While formal Islam is heavily male oriented, this "saint cult" allows more scope for women to take initiatives or even to display divine grace themselves. Conceptually linked with the complex of beliefs in saints are the mystical associations, known as "Sufi ways" or "orders." Here the stress is rather on a mystical loss of self in the divine, with the help of the teachings of a saintly individual. These Sufi orders are less evident in Tunisia than they used to be. Until the early twentieth century, their national leaders were often linked to the court of the bey of Tunis, they often had political roles, and their prestige was high. Later they suffered from their association with colonial power. The shrines associated with key figures in the history of these associations also often function as "saints" shrines, and often also as the centers of curing cults.

Death and the Afterlife. Muslims believe that the soul lives on after physical death. Corpses are buried quickly, the same day or early the next morning, in cemeteries reflecting the social identity of the dead person. The corpse is washed, wrapped in a shroud, carried to the cemetery by a group of mourners, and buried in a tomb. The body is laid on its left side facing Mecca. There are periodic commemorations

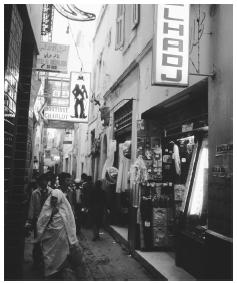

Side street stores on Kerkenna Island are packed with local shoppers on a Tunisian afternoon.

of the death, after seven and forty days, and sometimes after a year. Survivors also make visits to the tomb, men and women separately, and leave offerings for the soul of the dead person.

Medicine and Health Care

Tunisia has a modern system of health care with hospitals and clinics well distributed in the country. In addition, there are private doctors and hospitals. The University of Tunis has a medical school. Some doctors in the capital have formed associations to promote public health awareness, notably around the question of preventing pollution.

Traditional healers include bonesetters, dream interpreters, herbalists, and other specialists. Tunisians often seek mystical healing in a religious context. Modern alternative medicine, including acupuncture, is also found in cities.

Secular Celebrations

The national holidays are all evocations of the recent past of the country, and celebrate the markers of the nationalist history. They include independence from France (20 March 1956), the proclamation of the republic (25 July 1957), the adoption of the first constitution of the republic (1 June 1959), the final evacuation of the French military from Tunisia (15 October 1963), and the "change-over" when President Ben Ali was sworn in to replace Bourguiba (7 November 1987). These days are generally holidays from work.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. The government and some wealthy benefactors support the arts. One way of doing so is through national and local festivals devoted to one form or another of music, poetry, or folklore. These festivals include competitions, with prizes for the winner.

Literature. Tunisia has produced some fine writers, more in Arabic than in French.

Graphic Arts. Paintings, mosaics, and murals by Tunisian artists are commonly seen.

Performance Arts. Music plays a major role in everyday life in Tunisia, and many people are amateur musicians who perform in a circle of friends and neighbors. Professional performers appear in restaurants and nightclubs as well as in festivals. Tunisian drama is especially known for experimental theater, as well as for classical plays. Tunisian filmmakers have established a collective reputation for solid films, many of which deal with a coming-of-age in the recent historical past, so they are both psychological dramas and re-creations of the national narrative.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

The physical and social sciences are both concentrated in the University of Tunis. Also affiliated with the University of Tunis is the Centre d'Etudes et de Recherches conomiques et Sociales. There are other scientific research institutes, such as the Oceanographic Research Institute on the coast at Salammbo, near Tunis. Also attached to the University of Tunis is a center focusing on the national independence movement. Research quality is high, and many Tunisian scholars in these areas publish in Tunisian and non-Tunisian journals, usually in French.

Bibliography

Abdelkafi, Jellal. La Médina de Tunis, 1989.

Abu, Zahra, Nadia. Sidi Ameur, a Tunisian Village, 1982.

Allman, James. Social Mobility, Education, and Development in Tunisia, 1979.

Anderson, Lisa. The State and Social Transformation in Tunisia and Libya, 1830–1980, 1986.

Duvignaud, Jean. Change at Shebika: Report from a North African Village, 1970.

Dwyer, Kevin. Arab Voices: The Human Rights Debate in the Middle East, 1991.

Ferchiou, Sophie, ed. Hasab wa nasab: Parenté, alliance et patrimoine en Tunisie, 1992.

Green, Arnold. The Tunisian Ulama, 1873–1915: Social Structure and Response to Ideological Currents, 1978.

Hejaiej, Monia. Behind Closed Doors: Women's Oral Narratives in Tunis, 1996.

Hermassi, Elbaki. Leadership and National Development in North Africa: A Comparative Study, 1972.

Hopkins, Nicholas S. "The Emergence of Class in a Tunisian Town." International Journal of Middle East Studies 8: 453–491, 1977.

——. "The Articulation of the Modes of Production: Tailoring in Tunisia." American Ethnologist 5: 468–483, 1978.

Labidi Lilia, Çiabra. Hachma: Sexualité et tradition, 1989.

Murphy, Emma C. Economic and Political Change in Tunisia: From Bourguiba to Ben Ali, 1999.

Pierre, Amor Belhadi, Jean-Marie Miossec, and Habib Dlala. Tunis: Evolution et fonctionnement de l'espace urbain, 1980.

Salem, Norma. Habib Bourguiba, Islam, and the Creation of Tunisia, 1984.

Stone, Russell A., and John Simmons, eds. Change in Tunisia: Studies in the Social Sciences, 1976.

Udovich, Abraham L., and Lucette Valensi. The Last Arab Jews: The Communities of Jerba, Tunisia, 1984.

Waltz, Susan. Human Rights and Reform: Changing the Face of North African Politics, 1995.

Webber, Sabra J. Romancing the Real: Folklore and Ethnographic Representation in North Africa, 1991.

Weingrod, Alex. The Saint of Beersheba, 1990.

Zartman, William, ed. Tunisia: The Political Economy of Reform, 1991.

Zghal, Abdelkader. Modernisation de l'agriculture et populations semi-nomades, 1967.

Zussman, Mira. Development and Disenchantment in Rural Tunisia: The Bourguiba Years, 1992.