Culture of Trinidad and Tobago

Culture Name

Depending upon which island in this twin–island state is being discussed, the culture name is "Trinidadian" or "Tobagonian."

Alternative Names

Trinidadians, but not Tobagonians, often refer to citizens of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago as "Trinidadians" or "Trinis," or occasionally in an effort to be inclusive, as "Trinbagonians."

Orientation

Identification. Trinidad was named by Christopher Columbus on his third voyage to the New World. On the morning of 31 July 1498, he saw what appeared to him as a trinity of hills along the southeastern coast. The island was called Iere, meaning "the land of the hummingbird," by its native Amerindian inhabitants. Tobago's name probably derived from tabaco (tobacco in Spanish).

Trinidad (but not Tobago) is ethnically heterogeneous. Trinidadians and Tobagonians of African descent are called "Negro," "Black," or "African." Trinidadians of Indian descent are called "East Indian" (to differentiate them from Amerindians) or "Indian." More recently the terms "Afro-Trinidadian" (or "Afro-Tobagonian") and "Indo-Trinidadian" have gained currency, reflecting heightened ethnic claims to national status. Trinidadians of European ancestry are called "White" or "French Creole." There are a number of designations for those of black–white ancestry, including "Mixed," "Colored," "Brown," and "Red" among other terms. The term Creole, from the Spanish criollo , meaning "of local origin," refers to Blacks, Whites, and mixed individuals who are presumed to share significant elements of a common culture as well as biogenetic properties because most claim these designations do not represent "pure races." The term Creole thus tends to relegate non-Creoles like East Indians to a somewhat foreign status. Creole also serves to modify whiteness. The term "French Creole" refers to white families of long standing whether their surname is French-derived or not. The terms "Trinidad White" and "Pass as White" are sometimes used to deride those who are considered White in Trinidad but would not be so considered elsewhere. Trinidadians and Tobagonians (the population of Tobago is almost 100 percent of African descent) identify strongly with their home island and believe each other to be different culturally.

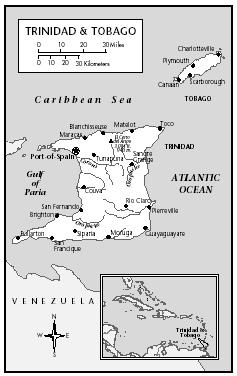

Location and Geography. Trinidad and Tobago are the southernmost islands in the Caribbean Sea. Trinidad is 1,864 square miles in area (4,828 square kilometers), and Tobago is 116 square miles (300 square kilometers). At its closest point, Trinidad is some seven miles from the coast of Venezuela on the South American mainland. Trinidad is diverse geographically. It has three mountain ranges, roughly parallel to each other, running east to west in the north, central, and south parts of the island. The mountainous north coast is heavily wooded. The central part of the island is more flat and is where sugar cane is grown. The East–West corridor is an urban–industrial conurbation from Port of Spain, the capital, in the west to Arima in the east. San Fernando in the south is Trinidad's second city. The Point Lisas industrial park is nearby. Scarborough is the capital of Tobago. Afro-Trinidadians and other Creoles predominate in urban areas and in the north of Trinidad; Indo-Trinidadians live mostly in the central and south parts of the island.

Demography. According to the 1990 census, the total population was 1,234,400. The two major ethnic groups are Blacks (39.59 percent of the population) and East Indians (40.27 percent). The remainder of the population in 1990 included Mixed, White, and Chinese.

Trinidad and Tobago

Linguistic Affiliation. The official language is English. At present, Trinidad is multilingual, with inhabitants speaking standard and nonstandard forms of English, a French-based creole, nonstandard Spanish, and Bhojpuri. Urdu is spoken in some rural areas. Arabic, Yoruba, Bhojpuri, Urdu and other languages are used in religious contexts, and the traditional Christmas music called parang is sung in Spanish. Trinidadians delight in their colorful speech and like to emphasize its distinctive use and development as a marker of identity. Standard and nonstandard English are spoken in Tobago.

Symbolism. The public symbols of the nation tend to evoke the themes of multiculturalism, unity in diversity, and tolerance. The national motto is "Together we aspire, together we achieve." The national anthem features the line "Here every creed and race find an equal place," which is sung twice for emphasis. Some public holidays and celebrations emphasize group contributions to the nation, including Independence Day (31 August), Emancipation Day (1 August; commemorating the ending of slavery), and Indian Arrival Day (30 May).

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. Claimed by Columbus for Spain, Trinidad was a forgotten Spanish colony for three hundred years. Native Amerindians died upon contact with European diseases, were forcibly exported to the mainland to work in mines, and those who survived were subject to Spanish missions and labor schemes. The African slave population was small during Spanish rule. The Spanish Cedula de Población of 1783 was designed to convert Trinidad into a plantation colony. It attracted white and colored French planters who brought their African and African-descended slaves to cultivate sugar and cocoa. While controlled by Spain, Trinidad became French in orientation and dominant language use. Captured by the British in 1797, the island was formally ceded to Britain in 1802. British administrators, British planters, and their slaves added to the island's ethnic, national, and linguistic diversity. Enslaved Africans arrived from varied ethnic, cultural, linguistic, and religious groups from along the West African coast, while Creole slaves spoke a French or English creole, depending on their islands of origin. Spanish-speaking peon laborers from Venezuela arrived in the nineteenth century to clear forests and work in cocoa cultivation. Even before the abolition of slavery in 1834 and the end of the apprenticeship system for ex-slaves in 1838, free Africans arrived. Blacks from the United States also settled in Trinidad. From 1845 to 1917, about 144,000 indentured Indians were brought to the island. The majority were from the north of India and were drawn from a multiplicity of castes. The vast majority were Hindus, but there was a significant Muslim minority. Planters were encouraging Portuguese speakers from Madeira and Chinese from the Cantonese ports of Whampoa and Namoa to come as indentured laborers.

Tobago developed separately, with the Spanish, French, Dutch, English, and Courlanders all laying claim to the island at different times. Plantation agriculture based on enslaved labor existed alongside a significant peasant sector. The British colonies of Trinidad and Tobago were united administratively in 1889.

Under British colonialism there was a clear ethnic division of labor, with Whites as plantation owners, Chinese and Portuguese in trading occupations, Blacks and Coloreds moving into the professions and skilled manual occupations, and East Indians almost completely in agricultural pursuits. Blacks and East Indians were separated geographically, as many Blacks were urban-based and East Indians were more numerous in the agricultural central and south parts of the island. There was little if any intermarriage and little intermating between the two groups. These divisions dictated the course of national identity and nationalist politics.

National Identity. The political process has molded ethnic relations. Colonial discourses on African and Indian ancestral culture depicted Blacks as culturally "naked" and Indians possessing a culture, albeit an inferior one to European culture. Perhaps for this reason, Blacks have emphasized Western learning and culture and Indians have emphasized the glories of their subcontinental past. Despite imposed divisions, Blacks and East Indians united in the nationalist labor movements of the 1930s. However, politics quickly became contested terrain. Political parties and candidates appealed to ethnicity. Oxford-trained historian Eric Williams (1911–1981) started the People's National Movement (PNM) in 1955 with other middle-class Blacks and Creoles. Williams maintained that the PNM was a multi-ethnic party, but its interests were soon identified with Blacks. The PNM held power from 1956 until 1986, leading the country to independence in 1962. Its perpetual opposition parties were identified as "Indian," given the composition of their leaders and followers. Politics became an ethnic zero-sum game.

With independence, symbols of the state and nation were conflated with what was taken to be Afro-Trinidadian culture, such as Carnival, the steel band, and calypso music—turning the colonial hierarchy on its head. Deviating cultural practices, such as "East Indian culture," were labeled as unpatriotic and even racist. The country was depicted as a melting pot where races mixed under the rubric of "creolization." Those who did not were less than Trinidadian. A discourse of the past entered, centering on arguments over which group historically contributed most substantially to building the nation, which therefore is construed as legitimately belonging to that group. There were two opposing but related processes at work. First, an identification of nation, state, and ethnicity to construct a "non-ethnicity" where there are "Trinidadians" and then there are "others," that is, "ethnics." There is also the construction of ethnic and cultural difference to prove and justify contribution, authenticity, and citizenship. Through the mid-1990s, Afro-Trinidadians and Creoles were able to command this discourse, but East Indians began to mount a serious challenge. At the same time, there was even a small group claiming "Carib" Amerindian identity.

Ethnic Relations. Post-independence ethnic relations have involved contests to control the state and the allocation of resources. The PNM maintained dominance through a patronage network targeted at urban Blacks as recipients. This was accomplished by a tremendous state expansion facilitated by the oil boom of the 1970s, which led to one of the highest standards of living in Latin America. Indo-Trinidadians were also able to take advantage of gains in education and fill lower-level state jobs. The government nationalized many industries, including sugar, which employed mainly Indians. A downturn in oil income severely limited state patronage opportunities. Albeit absent from formal politics, Whites, Chinese, Syrian, and some Indo-Trinidadian entrepreneurs control significant sectors of the economy. By 1986, several forces led to the formation of a black-Indian coalition party, the National Alliance for Reconstruction (NAR), that toppled the PNM. However, ethnic and personality strife broke the NAR apart, and the PNM won the next election. But by 1995, an Indian-based party, the United National Congress, barely prevailed, bringing to power the country's first Indo-Trinidadian prime minister, Basdeo Panday. While symbolic ethnic conflict seems to permeate daily life, it must be emphasized that Trinidad has never exploded in ethnic violence, as has its neighbor Guyana which has a similar demographic profile.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

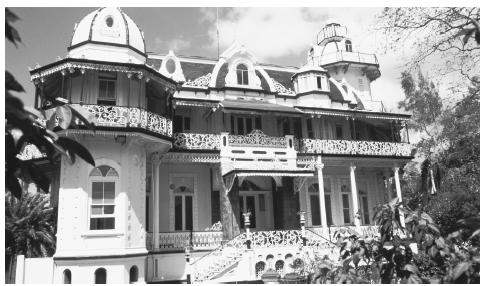

In cities, glass and steel high rise office buildings mingle with colonial houses with gingerbread fret-work. The colonial Red House is the parliament building, and Woodford Square, the site of political rallies, sits opposite. Exclusive neighborhoods feature modern and colonial mansions with satellite dishes. Concrete public housing projects evoke their counterparts elsewhere and shanty towns exist on the urban periphery. Suburban developments are reminiscent of American ranch-style houses. The ever-present cacophony in urban areas is the result of cars, taxis, "maxi-taxi" minibuses, street vendors, pedestrians, and the homeless jamming the streets. Women develop stock responses to men's "sooting" (cat calls). Development in rural areas means concrete houses built on pilings to allow a breezeway and carport underneath.

Iron lacing decorates a colonial style mansion in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Cuisine is ethnically marked. A typical Creole dish is stewed chicken, white rice, red beans, fried plantains, and homemade ginger beer. Indian food consists of curried chicken, potatoes, channa (chick peas), white rice, and roti , an Indian flatbread. Chinese food is typically chow mein. However, all of these are simultaneously regarded as national dishes and food metaphors are made to stand for the nation. Trinidadians are said by Creoles to be ethnically "mixed-up" like callaloo , a kind of soup made from dasheen leaves and containing crab. Crab and dumplings is said to be the typical Tobago meal. A society-wide concern for cleanliness is revealed when concerns over food preparation are voiced.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Indian food taboos and customs remain in some areas, while in others, the food customs are reinterpreted and take new form or are not relevant. A society-wide ethos valorizing generosity with food prevails, especially at ceremonial occasions. Trinidadian novelist V.S. Naipaul wrote in his travelogue The Middle Passage about Creoles that "Nothing is known about Hinduism or Islam. The Muslim festival of Hosein, with its drum-beating and in the old days stick-fighting is the only festival which is known; Negroes sometimes beat the drums. Indian weddings are also known. There is little interest in the ritual; it is known only that food is given to all comers." Creole knowledge of Indian rites is now considerable, as is their participation as guests at these events. Food is important in both Hindu and Muslim celebrations. In Christian families, sorrel, made from a flower, and ponche de creme, a kind of eggnog with rum, are typical Christmas drinks. Ham and pastelles are Christmas fare.

Basic Economy. Upon independence the PNM followed the colonial "industrialization by invitation" import substitution strategies to lure foreign capital and protect local manufacturers. The oil boom of 1974–1982 saw continuous real Gross Domestic Product growth averaging 6.1 percent a year, and during this time the government acquired and established a number of state enterprises, including oil and sugar companies. Government and private spending accelerated. Members of the expanding middle-class made frequent shopping trips to Miami and Caracas. The subsequent fall in oil prices meant losses in savings and foreign exchange, disinvestment, privatization, International Monetary Fund-directed trade liberalization policies, and general austerity. In the 1990s unemployment ran at more than 20 percent. Imported food and consumer goods are still prized. Agriculture occupations continued to decline as service industry occupations grew. By the end of the 1990s there was reason for optimism. In 1997, the economy grew by 4 percent, compared with a 1.5 percent contraction in 1993. Over the same period, inflation dropped to 3.8 percent from 13 percent. Income per capita (in 1990 dollars) rose from $3,920 to $4,290.

Land Tenure and Property. Land ownership is thoroughly commoditized and the government maintains significant holdings. The Sou-Sou Lands organization, named after a rotating credit association, redistributed land. Squatters remain in a number of areas. The Afro-Caribbean institution of "family land" exists in Tobago. A rural cooperative institution known as gayap is a means whereby some lands are cultivated and houses constructed.

Commercial Activities. There is considerable formal and informal market commercial activity in the sale of imported and locally-produced consumer goods. Towns like Chaguanas in central Trinidad have impressive high streets devoted to shopping. There are air-conditioned shopping malls around the country, supermarket chains, and small "mom and pop" shops ("arlors") with the owners living upstairs. Sales are fueled by a well-developed advertising industry and communications network. There are a number of regional open-air produce markets.

Major Industries. Government- and foreign-owned oil, natural gas, and iron and steel industries are the most important industries. A number of international goods are manufactured locally under license. Sugar is exported by the state firm. International tourism is underdeveloped in Trinidad, but government has taken steps for its promotion. Tobago is a growing international tourist destination.

Trade. Commodities sold on the international market include oil, steel, urea, natural gas, cocoa, sugar, and Angostura bitters. It is the world's second-largest exporter of ammonia and methanol. The major trading partner is the United States, but inroads were made in the late 1990s into Latin American markets.

Division of Labor. The traditional ethnic division of labor has tended to break down somewhat with time, but whites and other minorities have retained significant control of the economy. Firms owned by one ethnic group tend to have members of that group in management and as employees. State hiring is more credentials-based, despite the feeling among Blacks and Indians that certain sections of the public service are one or the other's preserve.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. Given ethnic diversity and ethnic politics, the salience of class is often overlooked or even actively denied. In fact, ethnicity and class work in tandem. Blacks and Indians have lagged behind other racial groups in earning power. Caste for Indians broke down with migration, but informal claims to high caste ancestry are still made at times.

Symbols of Social Stratification. Status symbols tend to be Western symbols—material possessions such as cars, the year model of which are designated by their license plates, houses, television sets, and dress. Education and use of standard English are key symbols of middle-class status. A tension exists between individualism and expectations of generosity. Upward mobility exposes one to community sanctions, captured by the proverb "The higher monkey climb, the more he show his tail."

Political Life

Government. The government of Trinidad and Tobago consists of a parliamentary democracy with an elected lower house and an appointed upper house. The prime minister—the leader of the party with the most seats in parliament—holds political power. The appointed president is the official head of state. The Tobago House of Assembly retains some autonomy.

Leadership and Political Officials. Political parties have for the most part made their appeals on the basis of ethnicity, even if not overtly, and nationalism, rather than on class or ideology. Cases of corruption have been highly publicized. The media, including tabloid newspapers, is particularly aggressive in making corruption allegations.

Social Problems and Control. High unemployment, especially for youth, is a central problem, spawning others. Since the 1980s, crime is seen as a serious problem, especially violent property crimes connected to the sale and transhipment of illegal drugs. Some also blame cable television and the Internet for inculcating North American values and aspirations. In neighborhoods and villages, gossip exerts control, although one loses status for being "long eye" (envious) or a maco , someone who minds the business of others.

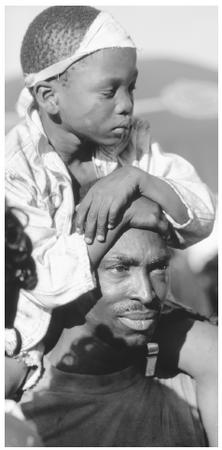

A boy sits on his father's shoulders during a Carnival procession. Carnival is a major celebration.

Military Activity. There is a small Defense Force and Coast Guard. These forces cooperate with the United States and other countries in drug interdiction.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

A number of programs exist with specific areas of interest. For instance, women's groups include Concerned Women for Progress, The Group, and Working Women. Servol is a Catholic organization based in Laventille, a slum area, that teaches job skills to youth. The Society of Saint Vincent de Paul is also active.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

Nongovernmental organizations range from influential religious groups, such as the Sanatan Dharma Maha Sabha, a Hindu organization, to FundAid, an NGO that funds small businesses. Fraternal and civic organizations are very popular among the middle classes. Trade unions are very organized and influential.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. Women have made many gains in the last three decades: they now join men as lawyers, judges, politicians, civil servants, journalists, and even calypsonians. However, despite generally better educational levels, women earn less than men, especially in private industry. Men dominate as artisans, mechanics, and oilfield riggers. Many occupations are dominated by women, such as domestic service, sales, and some light manufacturing. Many women are microenterprise owners. Sexual harassment has been a societal issue since the 1980s.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Power differentials remain salient in different contexts. Afro-Trinidadian women enjoy some autonomy and power within domestic domains and are often heads of households. Women are said to dominate in "playin' mas'," participating in Carnival, where they demonstrate an assertive sexuality. Women are marginalized from leadership positions in the established churches, Hinduism, and Islam, but are influential in the Afro-Christian sects. Women run the sou-sou informal rotating credit associations. An active women's movement has put domestic violence, rape, and workplace sexual harassment on the public agenda.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Marriage practices differ according to ethnicity and class, although for both blacks and Indians kinship is bilateral in structure. For the middle and upper classes, formal marriage with religious sanction is the norm. Legal recognition for Hindu and Muslim marriages came very late in the colonial period. In the past, East Indian women were betrothed in arranged marriages at young ages.

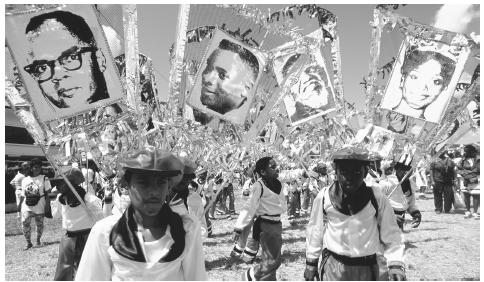

Children marching in the Junior Parade of the Bands in Queen's Park Savannah. Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago.

Many Afro-Trinidadians entered into noncoresidential relationships, then common-law marriages, and then, later in life, formal marriage. There is evidence that this is changing, with the age of marriage for Indian women increasing along with their propensity to enter non-coresidential relationships, and the importance of arranged marriages greatly diminished. The prevalence of noncoresidential relationships is increasing for the upper classes as well. Many Indo-Trinidadians see creolization as tantamount to miscegenation. Given the persistence of colonial stereotypes of Blacks, there has generally been strong Indian resistance to intermarriage with Blacks.

Domestic Unit. As with marriage patterns, the domestic unit has historically varied with class and ethnicity. Upper class families are often multi-generational. Many working-class Afro-Trinidadian households are female-headed, and multi-generational. In the past, a married Indian couple lived with the husband's extended family; however, neolocal residence is increasingly seen as the preferred form.

Inheritance. Among East Indians and upper class others, inheritance was patrilineal. This has become more egalitarian in terms of gender. Among Afro-Trinidadians, inheritance patterns have not necessarily favored males. There are often disputes over the inheritance of land.

Kin Groups. Fictive kinship and godparenthood are important institutions. Most families have migrant kin abroad, some who play significant roles with visits and remittances.

Socialization

Infant Care. Practices vary somewhat significantly according to ethnicity, class, and the age and education of the parents and/or caretakers. Middle class parents read North American child care books and often are knowledgeable of the latest trends. Still, there are some commonalities. For all groups, older siblings, kin, and neighbors often play significant roles. Infants are not confined to separate spaces or playpens and often sleep in the same bed as the caretaker. Infants are carried in arms from place to place. Strollers or prams are not used. Car seats for safety are becoming popular. Many toddlers are sent to pre-schools and nurseries by age two. Corporal punishment in public for toddlers is common.

Child Rearing and Education. Values inculcated vary by ethnicity, class, and the sex of the child. In general, caretakers, be they parents, grandparents, or other kin or fictive kin, are quick to discipline children. "Back chat" to an adult is not permitted. Children are expected to show that they are "broughtupsy" having decorum, but not to the point of being "social" (pretentious). A "harden" (disobedient) child or a wajang (rowdy, uncouth) youth involved in commesse (scandal, acrimony) is an embarrassment to the family. Boys are expected to be aggressive and, as they get older, sexually aware, but respectful to adults. Ideally, girls do not have free reign. Most girls are encouraged to emphasize physical beauty.

Higher Education. The society places a high value on higher education and many parents and kin make great sacrifices to enable students to reach their educational goals. In the past, training for white-collar professions was favored and emphasized, and titles and diplomas were fetishized. Status is attached to better secondary schools, such as Queen's Royal College (state) and Catholic Church-affiliated Saint Mary's College for boys and Saint Joseph's Convent for girls. The Trinidad campus of the regional, comprehensive University of the West Indies (UWI) is in Saint Augustine (other sites are in Barbados and Jamaica). UWI in Trinidad began in 1960 when the Imperial College of Tropical Agriculture became the Faculty of Agriculture of the University College of the West Indies, University of London. Many citizens with higher education were trained abroad and they often emigrate permanently.

Etiquette

While class and ethnic differences matter, as do contexts, sociability and gregariousness are generally highly valued. Business settings require more subdued behavior, but it is not considered good form to talk about one's work endlessly at cocktail parties. Middle-class men receive status for offering their comrades imported Scotch whiskey. In general, punctuality is not expected. "Trinidad time" refers to habitual lateness and "jus' now" means "in a little while" but in practice can mean hours. On city streets it is common for men to verbally harass women and women generally lose status if they reply. In country districts, it is expected that one salutes passers by with a "good morning" or "good aftimiernoon." Slarly, one should begin phone conversations, address fellow passengers upon entering a taxi, and address occupants when entering a room or a home with a "good morning," "good afternoon," or "good night."

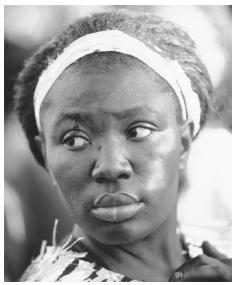

Women are often heads of households.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. The country is noted for its religiosity and religious diversity. In 1990, the majority religion was Roman Catholic, encompassing 29 percent of the population. The majority of Indians are Hindu, but many are Christians, resulting from Canadian Presbyterian missions in the nineteenth century. Evangelical Christian sects from North America are growing rapidly. American Muslim groups claim adherents. There are followers of Sai Baba and Rastafarians. Afro-Christian forms of worship are prevalent, such as the Orisha religion and the Spiritual Baptists, and worship in these is not exclusive of membership in established churches. There are folk beliefs in jumbies (ghosts, spirits). Official religious holidays include Divali (called Holi in India; Hindu), Eid (Muslim), Spiritual Baptist Liberation Day (30 March), Good Friday, Corpus Christi, and Christmas Day. The two days before Ash Wednesday, when Carnival is held, and Phagwa (Hindu) and Hosay (Muslim) are holidays for all intents and purposes.

Religious Practitioners. Religious leaders include imams (Muslim), pundits (Hindu), priests (Anglican and Catholic), Orisha and Spiritual Baptist leaders. There is a hierarchy in established churches, with a Catholic archbishop and an Anglican bishop at the head of those communities.

Ritual and Holy Places. On Holy Thursday night, thousands of Hindus pay homage to a carved wood statue of the Madonna at the Catholic church at Siparia. Weeks later, Catholics parade the same statue through the streets. In the past, Chinese came to honor the statue when it passed on the street. Places of worship, such as the Holy Trinity Cathedral in Port of Spain and the Abbey of Mount Saint Benedict, a functioning monastery, are seen as holy places. The Caroni River, where Hindu cremations are held, is an important ritual and holy place.

Death and the Afterlife. Funerals and all-night wakes, called "sit-ups," are important social occasions. Obituaries are read on the radio. Cremation at the Caroni River is practiced for Hindu Trinidadians.

Medicine and Health Care

There is a national health service, but private medicine serves a large share of the population. Both are based on the Western bio-medical model. There are traditional healers, some related to Afro-Christian forms of worship. Many ordinary citizens use herbal teas and bush medicine for everyday ailments. Drug addiction and AIDS are seen as serious problems and the country has one of the highest AIDS rates in the world.

Secular Celebrations

Besides Emancipation, Independence, and Indian Arrival days, official secular holidays include New Year's Day, Easter Monday, Labour Day (19 June), when 1930s labor leader T.U.B. Butler and the trade union/nationalist movement are commemorated, and Boxing Day (26 December). The pre-Lenten Carnival is the biggest secular celebration.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. The government supports Carnival, the Best Village competition (which includes dance, music, and drama), the National Youth Orchestra, the biennial Music Festival, and the National Museum.

Literature. An impressive literary tradition exists among writers who have mainly made their names and reputations abroad, including C.L.R. James, Ralph de Boissie`re, V.S. Naipaul, Shiva Naipaul, Samuel Selvon, Earl Lovelace, Ismith Khan, Ramabai Espinet, and Michael Anthony. Calypso must count as oral literature. Contemporary calypsonians include the Mighty Sparrow, Lord Kitchener, the Mighty Chalkdust, Gypsy, Black Stalin, Drupatee, Cro Cro, Calypso Rose, Super Blue, David Rudder, Crazy, Baron, Explainer, Sugar Aloes, and Denyse Plummer among many others. Relatively new music forms are Indian music-influenced "chutney" and "pitchakaree," performed by well-known singers such as Sundar Popo, Anand Yankaran, Heeralal Rampartap, Savitri Jagdeo, Vinti Mohip, Jagdeo Phagoo, and Ramraajee Prabhoo.

Graphic Arts. Trinidad's best known artist is perhaps the painter Michel Jean Cazabon (1813–1888). Some of the better-known artists of the past few decades are Dermot Louison, M.P. Alladin, Sybil Attek, Amy Leong Pang, Pat Chu Foon, and the sculptor Ralph Baney. Active living artists include Carlisle Chang, LeRoy Clarke, Boscoe Holder, Francisco Cabral, Pat Bishop, Isaiah Boodhoo, Ken Crichlow, Wendy Naran, and Jackie Hinkson. A younger generation includes Eddie Bowen, Kathryn Chang, Chris Cozier, and Che Lovelace. A recent appreciation of untrained artists has resulted in the establishment of the Museum of Popular and Folk Art.

Performance Arts. Carnival is Trinidad's most noteworthy performance art, attracting tourists, emigrated Trinidadians, and scholars from abroad. Masquerade designer Peter Minshall is one of the best known internationally. He was artistic director for the opening and closing ceremonies of the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona, the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, and the 1994 World Cup opening ceremony in the United States. Live calypso and steelband performances occur in the Carnival season (Christmas through Lent). A dance performance tradition centers around Beryl McBurnie and the Little Carib Theatre.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

In 1961, the UWI Faculty of Engineering opened. In 1963, teaching in the arts, natural, and social sciences began. There are a number of research institutes, such as the Centre for Ethnic Studies, the Centre for Gender and Development Studies, and the Institute of Social and Economic Research. In Tobago the government-run Hospitality and Tourism Institute offers tourism training. Some locallybased social scientists are very visible as pollsters, newspaper columnists, and television analysts.

Bibliography

Braithwaite, Lloyd. Social Stratification in Trinidad , 1975 [1953].

Brereton, Bridget. A History of Modern Trinidad 1783– 1962 , 1981.

Harewood, Jack, and Ralph Henry. Inequality in a Post-Colonial Society: Trinidad and Tobago , 1985.

Hill, Errol. The Trinidad Carnival: Mandate for a National Theatre , 1972.

LaGuerre, John G., ed. Calcutta to Caroni: The East Indians of Trinidad , 1985 [1974].

Mendes, John. Cote ce Cote la: Trinidad and Tobago Dictionary , 1986.

Miller, Daniel. Modernity—An Ethnographic Approach: Dualism and Mass Consumption in Trinidad , 1994.

Oxaal, Ivar. Black Intellectuals and the Dilemmas of Race and Class in Trinidad , 1982.

Reddock, Rhoda E. Women, Labour and Politics in Trinidad and Tobago: A History, 1994.

Rohlehr, Gordon. Calypso and Society in Pre-Independence Trinidad , 1990.

Ryan, Selwyn, ed., Trinidad and Tobago: The Independence Experience 1962–1987, 1988.

Stuempfle, Stephen. The Steelband Movement: The Forging of a National Art in Trinidad and Tobago , 1995.

Vertovec, Steven. Hindu Trinidad: Religion, Ethnicity and Socio-Economic Change , 1992.

Wood, Donald. Trinidad in Transition: The Years After Slavery , 1968.

Yelvington, Kevin A., ed. Trinidad Ethnicity , 1993.

——. Producing Power: Ethnicity, Gender, and Class in a Caribbean Workplace , 1995.