Culture of Tonga

Culture Name

Tongan

Alternative Names

Friendly Islands

Orientation

Identification. The name "Tonga" is composed of to (to plant) and nga (a place). It also means "south." According to the most recent archaeological findings, people arrived in the archipelago from Fiji around 1500 B.C.E. Thus, it is appropriate to translate the nation's name as "land lying in the south."

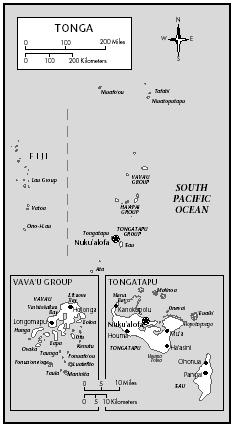

Location and Geography. Tonga is an archipelago of one hundred fifty islands, thirty-six of which are inhabited. There are four major groups of islands: the Tongatapu, Ha'apai, Vava'u, and Niua groups. Most of the islands are raised coral islands, some are volcanic, and a few are atolls. Coral beaches lined with palm trees and emerald lagoons with luxuriant tropical vegetation are characteristic features. The capital, Nuku'alofa, is on Tongatapu.

Demography. The population was 97,784 according to the 1996 census. Since 1891, the growth rate has increased steadily, peaking in the 1950s and 1960s. Migration to New Zealand, Australia, and the United States in the 1970s and 1980s resulted in slower growth. Internal migration has been from the outer, northern, and central islands toward the southern island of Tongatapu. A third of the population (31,404) lives in the capital.

Linguistic Affiliation. Tongan is an Austronesian language of the Oceanic subgroup. It belongs to the Western Polynesian languages, specifically the Tongic group. There are three social dialects: one for talking to the king, one for chiefs and nobles, and one for the common people. "Talking chiefs" are among the few who know all three dialects; they mediate in official ceremonies and in encounters between the king, the nobility, and the commoners.

Seventy years as a British protectorate (until 1970) resulted in widespread knowledge of English. Though much of the village population knows little English, in Nuku'alofa and other major towns, most business transactions are conducted in it. English is taught in elementary schools and is the language of most high school instruction. However, Tongan is the language commonly spoken in the streets, shops, markets, schools, offices, and churches.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. The Tongan creation myth describes how the islands were fished from the ocean by Maui, one of the three major gods. Another myth explains how 'Aho'eitu became the first Tu'i Tonga (king). He was the son of a human female and the god Tangaloa. Human and divine at the same time, the Tu'i Tonga was the embodiment of the Tongan people, and this is still a powerful metaphor.

Tongans were fierce warriors and skilled navigators whose outrigger canoes could carry up to two hundred people. For centuries they exercised political and cultural influence over several neighboring islands. By the time of the first European contact in late 1700s and early 1800s, the empire had collapsed, and the authority of the Tu'i Tonga was restricted mostly to the religious realm.

National Identity. King George Tupou I, the first king of modern Tonga, introduced the constitution in 1875 after unifying the four island groups. He had previously converted to Christianity and opportunistically waged expansionist wars from Ha'apai to Vava'u and then to Tongatapu. Christian principles characterize the constitution, which very likely was prepared under the influence of Wesleyan

Tonga

missionaries. George Tupou I transformed Tonga into a modern state, abolishing slavery and the absolute power of chiefs. Since the last Tu'i Tonga had no official heir, as the head of the other two royal lines, King George became the only king of Tonga. The 1875 constitution recognizes only his royal line.

In 1900, the British granted Tonga's request for protectorate status. In 1970, all powers were restored to the Tongan monarchy. The British protectorate shielded Tonga from other colonizing powers. A spirit of independence and pride was nurtured during the long reign of Queen Salote (1918–1965), who led the nation into the twentieth century, paying special attention to preserving its heritage. Because of her vision, Tongan culture is an integral part of the school curriculum. Students learn Tongan history, traditional poetry, music, and dancing, along with wood carving, mat weaving, and bark cloth making.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

The first European visitors spoke of a population scattered throughout a densely cultivated land. Now Tongans are concentrated in villages and small towns. Most villages lie around an empty area, called mala'e , that is used for social gatherings and games. A traditional house stands on a raised platform of stones and sand. It is oval in shape with a thatched roof and walls of woven palm tree panels. The toilet and the kitchen are in separate huts. Contemporary houses are usually bigger and made of timber with corrugated iron roofs. Little furniture is used.

The simplicity of house architecture contrasts with the monumentality of earlier royal buildings and tombs. The royal tombs are layered pyramidal structures built of massive stone slabs. The huge Ha'amonga trilithon, made of two stone columns topped with a notched column, was built around 1200 C.E. One hypothesis suggests that it was the door to the royal compound, and another that it was used for astronomical purposes. These monuments bear witness to the power of the Tu'i Tonga. They also indicate the sophisticated stone-cutting technology and skills of the ancient craftsmen.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Both in villages and in the main towns, food is the occasion for a family gathering only at the end of the day. Otherwise, food is consumed freely at any time. The basic staples are root crops like taro accompanied by fried or roasted meat or fish. Taro leaves are one of the various green vegetables used together with a variety of tropical fruits like bananas, pineapples, and mangoes.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. The ritual of kava drinking characterizes both formal and daily events. Kava is prepared by grinding dried roots and mixing the powder with water in a ceremonial bowl. It is nonalcoholic but slightly narcotic. People sit cross-legged in an elliptical pattern whose long axis is headed by the bowl on one side and by the highest-ranked participant on the other. The preparation and serving of the drink are done by a young woman, usually but not always the only female participant, or by male specialists. The

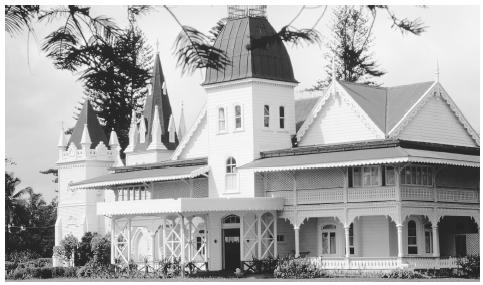

The royal palace in Nukualofa. Tonga is a constitutional monarchy.

formal coronation of a ruler and formal receptions for foreign delegations are marked by a kava ceremony. Kava clubs are found in the towns, and kava drinking gatherings take place almost daily in the villages.

Basic Economy. The economy centers on agriculture and fishing. Major exports are vanilla, fish, handicrafts, and pumpkins grown for export to Japan. King Taufa'ahau Tupou IV has modernized the country's economy. Based largely on foreign aid from New Zealand, Australia, the United States, and the European Community and on imports, this process has created a widespread presence of Western products. The agricultural base of the economy remains. The tourist industry is growing, and revenues from Tongans working abroad are one of the largest sources of income.

Typical agricultural produce are root crops such as taro, tapioca, sweet potatoes, and yams. Coconuts, bananas, mangoes, papayas, pineapples, watermelons, peanuts, and vegetables are grown. Pigs and fowl are abundant and free ranging. Cows, sheep, and goats also are present. Intensive shellfishing is conducted along the shores, and there is an abundant fish supply.

Royal visits and funerals call for the preparation of large amounts of food. Roasted piglets are laid in the center of a pola (tray) made of woven palm tree leaves. Root crops, meats, and shellfish prepared in the 'umu (underground oven) are added and garnished with fresh fruits, decorative flowers, ribbons, and balloons. In villages, food is consumed while one sits on a mat; in towns, tables are used.

Land Tenure and Property. All land is owned by the king, the nobles, and the government. Foreigners cannot own land by constitutional decree. Owners have the right to sublet land to people who pay a tribute, traditionally food. Every citizen above age 16 is entitled to lease eight and a quarter acres of land from the government for a small sum, but the growing population and its concentration in the capital make it increasingly difficult to exercise this right.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. Traditional society had at its top the ha'a tu'i (kings), followed by the hou'eiki (chiefs), ha'a matapule (talking chiefs), kau mu'a (would-be talking chiefs), and kau tu'a (commoners). All titles were heritable and followed the male line of descent almost exclusively. This hierarchical social structure is still essentially in place.

Tribute to the chiefs was paid twice a year. Agricultural produce and gifts such as butchered animals, bark cloth, and mats were formally offered to the Tu'i Tonga and, through him, to the gods in an elaborate ceremony called 'inasi . The king now visits all the major islands at least once a year on the occasion of the Royal Agriculture Show. The gift giving and formalities at the show closely resemble those of the 'inasi .

The 1875 constitution eliminated the title of chief and introduced the title of nopele (noble), which was given to thirty-three traditional chiefs. Only nobles and the king are now entitled to own and distribute land. An increasingly market-oriented economy and an expanding bureaucracy have recently added a middle class that runs the gamut from commoners to chiefs. Newly acquired wealth, however, does not easily overcome social barriers rooted in history. Often claims to higher social status are established by claiming kinship to holders of aristocratic titles.

Political Life

Government. The Kingdom of Tonga is a constitutional monarchy. The constitution prescribes a legislative assembly with twenty members representing the thirty-three nobles and twenty members elected as people's representatives. In 1984, both groups were reduced to nine each. Twelve other members are appointed by the king: ten Cabinet members including the prime minister, who is also the governor of Tongatapu, and the governors of Ha'apai and Vava'u. In the 1993 election, six of the people's representatives belonged to the new Pro-Democracy Movement that in 1994 became the Democratic Party founded by 'Akilisi Pohiva.

The kingdom is divided into districts, each headed by a district officer. Every three years, each village elects a town officer who represents the government and holds village meetings ( fono ) where government regulations are made known. Every villager above 16 years of age is entitled to attend. People do not take part in the decision-making process but show approval or dissent through their implementation of the instructions.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

Every citizen is entitled to free primary education, a plot of land at age 16, and free medical care. Hospitals, dispensaries, and pharmacies are distributed over the territory. Smaller government clinics are present in some villages in the outer islands.

To support the modernization of the country, in 1977 the Tongan Development Bank was established. Financed by the World Bank and contributions from New Zealand and Australia, it provides low-interest loans for entrepreneurs. Foreigners who want to invest in the country need a Tongan partner for any economic venture.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

The U.S. Peace Corps, the Japanese Overseas Cooperation Volunteers, and development organizations connected with the British, New Zealand, and Australian governments are among the active aid agencies. They work in the fields of education, health, agriculture, and entrepreneurship.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. The introduction of wage labor in twentieth century privileged men, altering an equilibrium between genders that had lasted for centuries. Cash is now an element of wealth, and wage-earning men have easier access to it. However, the old egalitarian attitude toward the two sexes has not been altered by economic and technological changes. In contemporary offices, shops, and banks, working women are prominent. In villages, most men take care of the land or tend animals. Women weave mats and make bark cloth.

Both women and men actively participate in parenting. Food preparation is shared between the male and female members of a family. The preparation of the 'umu (underground oven), now restricted to Sundays and special occasions, is an almost exclusive male activity. Older children help with activities and household chores.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. The hierarchical system's emphasis on the higher status of females guarantees an equal role in society for females and males in spite of the fact that men usually inherit titles and land.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. There are no explicit rules for marriage, and couples are formed through reciprocal free choice. Pronounced social stratification discourages marriages between people of vastly different social status. Divorce is legal and not uncommon. During a wedding, the two kainga involved exchange mats, bark cloth, and food. On the day of the ceremony, the bride and groom "wear their wealth." They are wrapped in their best mats and bark cloth, their

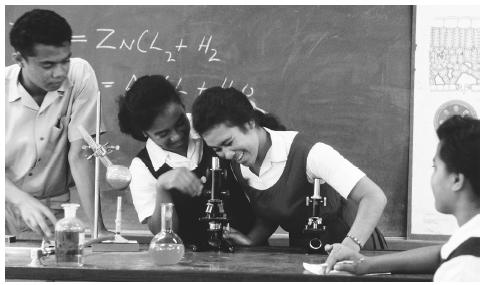

Tongan students use microscopes as part of a science experiment. Tonga has an almost universal rate of literacy.

bodies shine with precious oils, and they wear flower necklaces and hair adornments.

Kin Groups. Kinship ties are of paramount importance. The two major kin groups are famili (family) and kainga (extended family). A famili consists of a married couple and their children living in the same house and usually includes male and/or female collaterals and affinals. The 'ulumotu'a (head of the family) presides over this group. A kainga consists of relatives living in different households in the same village or in several villages. They are related by bilateral relationships of consanguinity in a cognatic system. Membership in kin groups is restricted to fewer and closer relatives than it was in the past.

The parameters in establishing hierarchy at any level of society are gender and age. A female is always considered higher in rank than a male. Inheritance of land and titles goes through the male line, and primogeniture rule usually is enforced. Because of traditional brother-sister avoidance, 10-year-old boys sleep in a separate house. Though avoidance is less strictly enforced now, it still affects daily life. Topics such as sex and activities such as watching videos are not shared between brothers and sisters.

Socialization

Infant Care and Child Rearing. The birth of a child is among the most important events, but the official social introduction of a child to the community is celebrated only at the end of a child's first year. Mothers increasingly give birth in modern hospitals, and infant mortality has decreased. Infants typically are breast-fed and sleep in their parents' bed until age 5 to 8 years. Parents are the main caretakers, but in an extended family everybody contributes to parenting. This feeling of shared parenting extends as far as the village and even further. Older siblings often care for younger ones, but compulsory education has made this practice less common.

Tongans are proud of their almost 100 percent level of literacy. Government high schools limit enrollment by using a competitive examination and charging fees. Those who are not admitted can attend private religious high schools. There is a branch of the University of the South Pacific on Tongatapu. Sia'atoutai Theological College trains teachers. 'Atenisi University, a private institution in Nuku'alofa, offers degrees in the humanities.

Adoption is common. An older couple whose children have left to form their own families may adopt from a younger couple with many children. A couple may decide to give a child to a relative of higher social or economic status, and many parents who work abroad leave their children with relatives. Children are present in private or public events and are almost never forbidden to look, observe, and learn.

The most important life events are celebrated with elaborate ceremonies that may last weeks in the case of weddings or funerals of royalty or nobles. These events include a complex pattern of gift exchanges; the preparation, consumption, and distribution of a large quantity of food; and speech giving. Pieces of bark cloth, mats, kava roots, and food are exchanged. Speakers use an elaborate figurative language.

Etiquette

Formal attire for men includes a tupenu (skirt) and a ta'ovala (mat) worn around one's waist and kept in place by a belt of coconut fiber. Prestigious old belts made of human hair also are used. A shirt with a tie and a jacket complete the attire. Women wear long dresses and ta'ovala as well. The softness, color, and decorations of a ta'ovala indicate status and wealth.

People shake hands when they meet, and relatives kiss by pressing each other's noses against their faces and soundly inhaling through the nose. The men preparing the 'umu or roasting for a big feast do not eat with the guests and are allowed at the table only when the first round of people has finished eating and left. Most food is eaten with the hands, although silverware also is used. It is customary to wash one's hands at the beginning and end of a meal.

The gesture of raising the eyebrows in conversation expresses one's understanding of the speaker's speech and is an invitation to continue. It is difficult for people to admit failure in understanding or to respond negatively to requests.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Christian churches exist in even the most remote villages. Bells or log drums call people for services at the crack of dawn. After a failed attempt by Wesleyan missionaries to Christianize the islands in 1797, they and other Christian missionaries were more successful in the mid-nineteenth century. Forty-four percent of Tongans belong to the Free Wesleyan Church. Wesleyanism is also the official religion of the state and the monarchy. Among the other major churches are the Roman Catholic Church (16.3 percent), the Church of Latter Day Saints (12.3 percent), the Free Church of Tonga (11.4 percent), the Church of Tonga (7.5 percent), Seventh-Day Adventist Church (2.3 percent), and Anglican Church (0.6 percent).

Medicine and Health Care

Traditional medicine exists alongside Western medicine in the person of the faito'o (native doctor). Knowledge about medicine is passed on from parent to child. The faito'o uses mainly herbal medicines. No payment is required for treatment, but gifts are given at the beginning or end of the cure. Massage is also used. Sometimes in the outer islands traditional medicine is the only defense against a number of diseases. Although people recognize the effectiveness of Western medicine, traditional medicine is highly respected.

Secular Celebrations

Besides Constitution Day (4 November) and Emancipation Day (4 June), the major secular holiday is the king's birthday on 4 July. Nobles and chiefs from all over the kingdom present gifts to the king in a ceremony adjacent to the royal palace. The capital is adorned with festive arches covered with fragrant flowers under which floats parade. After the parade, people feast and light bonfires.

The Arts and Humanities

Graphic Arts. Women make bark cloth that can reach fifty feet in length and fifteen feet in width. The design of the carved tablets used to decorate bark cloth is traditionally purely geometrical. Naturalistic figures such as trees, flowers, and animals are also used. Women also weave mats and make flax baskets. Color, thinness, and the number of threads used determine the quality of a mat. The uniformity and consistency of the patterns reveal a weaver's skill. These activities are always conducted in groups while talking, gossiping, or singing.

Men carve wood, black coral jewelry, and objects made of turtle shell or whalebone. Seeds, shells, and fresh flowers are woven into necklaces by both sexes.

Performance Arts. Choral singing is done in churches and kava clubs. Singing is part of the more holistic traditional art of faiva , the blending of dance, music, and poetry. The punake (master poet) composes pieces that combine music, text, and body movements. Traditional dances include the Me'etu'upaki (paddle dance), the Tau'olunga (solo dance), and the Lakalaka (line dance).

Bibliography

Barrow, John. Captain Cook: Voyages of Discovery , 1993.

Benguigui, G. "The Middle Classes in Tonga." The Journal of the Polynesian Society 98(4): 451–463, 1989.

Bennardo, G. A Computational Approach to Spatial Cognition: Representing Spatial Relationships in Tongan Language and Culture , 1996.

Campbell, I. C. Island Kingdom: Tongan Ancient and Modern , 1992.

Ferdon, E. N. Early Tonga: As the Explorers Saw It 1616– 1810 , 1987.

Gailey, C. W. Kinship to Kinship: Gender Hierarchy and State Formation in the Tongan Islands , 1987.

Gifford, E. W. Tongan Myths and Tales , 1924.

——. Tongan Society , 1929.

Hoponoa, Leonaitasi. The Aesthetic of Haka as a Component of the "Art" of Faiva: Differences between Referential and Non-Referential Constructions , 1996.

James, K. "Gender Relations in Tonga 1780 to 1984." The Journal of the Polynesian Society 92(2): 233–243, 1985.

Kaeppler, A. L. Poetry in Motion: Studies of Tongan Dance , 1993.

Kingdom of Tonga. Sixth Development Plan: 1991–1995 , 1999.

Kirch, P. V. "A Brief History of Lapita Archaeology." In P. V. Kirch and T. L. Hunt, eds. Archaeology of the Lapita Cultural Complex: A Critical Review , 1988.

Latukefu, S. Church and State in Tonga , 1974.

Law of Tonga, The , rev. ed., 1985.

Morton, Helen. Becoming Tongan: An Ethnography of Childhood , 1996.

Pawley, A. "Austronesian Languages." In Encyclopedia Britannica , 13th ed., 1974.

van der Grijp, Paul. Islanders of the South: Production, Kinship, and Ideology in the Polynesian Kingdom of Tonga , 1993.

Whistler, W. Arthur. Tongan Herbal Medicine , 1992.

Wood-Ellem, Elizabeth. Queen Salote of Tonga: The Story of an Era 1900–1965 , 1999.