Culture of Taiwan

Culture Name

Taiwanese; Formosan

Alternative Name

Republic of China

Orientation

Identification. Over four-fifths of the people are descendants of Han Chinese settlers who came to the island in the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries from southeastern China. They were joined in 1949 by remnants of the Nationalist party and army that left China after their defeat in the Chinese Civil War (1927–1949). The island's original inhabitants ( Yuanzhumin ), who are related to Malayo-Polynesian peoples of Southeast Asia, have lived on the island for thousands of years. The culture is a blend of aboriginal cultures, Taiwanese folk cultures, Chinese classical culture, and Western-influenced modern culture. The Nationalists have failed to impose a Chinese national culture on the island, and the potential for a Taiwanese national culture is held in check by both the Nationalists and the People's Republic of China (PRC) as they contest the country's sovereignty.

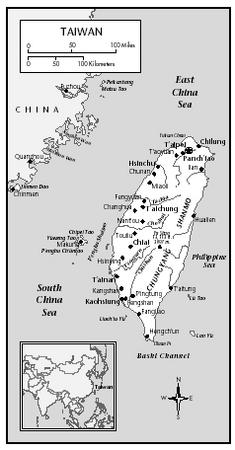

Location and Geography. Taiwan lies between Japan and Philippines, off the southeastern coast of China. The total area is 13,800 square miles, (32,260 square kilometers). A massive mountain range covers two-thirds of the island and includes East Asia's highest peak, Yü Shan. The subtropical climate is affected by two weather patterns: a continental monsoon that brings cool, wet weather to the northern half of the island between October and March and an ocean monsoon that brings rain to the southern half between April and September. The monsoons can bring devastating typhoons. Most mainlanders live in the north, Taiwanese live along the western coast, and aborigines live in the mountains and on the eastern coast.

Demography. With an estimated population of 22,113,250 in 1999, Taiwan is the second most densely populated country in the world. Seventy percent of the population is Hokkien, 14 percent is Hakka, 14 percent is Mainlander, and two percent is aboriginal. The population is 56 percent urban.

Linguistic Affiliation. Mandarin Chinese is the national language and the language of education, government, and culture. Taiwanese speak Taiyu, a southern Min dialect ( nanminhua ), or Hakka. There are seven distinct aboriginal languages, which are grouped into three language families. Most Taiwanese and aborigines speak both a local language and the national language. Mainlanders are monolingual, although some second-generation mainlanders speak Taiwanese.

Symbolism. The symbols of the national culture are conspicuous on the Double Ten (10 October), a national holiday that commemorates the founding of the Republic of China (ROC) in 1911. In Taipei, the Presidential Office Building is lit up and covered with a colossal portrait of Sun Yat-sen, the ROC's founding father. The highlight of the parade is a city-block-long dragon, a symbol of imperial China and the ROC's recently abandoned claim to be the legitimate government of all of China and the preserver of the Chinese cultural heritage. A large military presence reminds onlookers of the government's determination to defend the homeland against communist aggression. High school marching bands in brightly colored uniforms are symbols of the modern educational system and modernity in general. Students from the eastern coast dress in aboriginal costumes to symbolize the government's paternalistic benevolence. Missing from the parade are aborigines who advocate self-determination and the Taiwanese goddess and protector Mazu, who is a potent symbol of popular culture, a local variant

Taiwan

of China's Little Tradition that resists the inculcation of an elite Chinese national culture.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. The earliest record of human habitation on Taiwan dates back ten thousand to twenty thousand years. The origin of the first inhabitants is open to debate. Linguistically, the aborigines are related to the Austronesian language family, which points to a southern origin in Southeast Asia. Early stone tool and ceramic styles have been placed in the same traditions as those of Fujian and other mainland sites and suggest a northern origin. A third theory proposes that Taiwan is the homeland of Austronesian culture and language and the source of migrations throughout the region. These theories have become politically charged, with aborigines and opposition party members favoring either the southern origin or homeland theory, and mainlanders favoring the northern origin theory.

Most of the Han settlers came from southern Fujian Province and eastern Guangdong Province, beginning in the seventeenth century. The pioneer era can be divided into three stages marked by different agendas and ethnic tensions. In the early stage (1683–1787), settlers reclaimed land and established farming communities. This period was relatively peaceful except for conflict between Han settlers and the aborigines. The second historical period (1788–1862) saw growth in agricultural production and markets, and leaders representing dominant surname groups competed for control of agricultural production and the lucrative market in grain and sugar. This was a violent period, with numerous uprisings and rebellions that pitted groups identifying with different homelands against one another. This fighting fortified ethnic identities and divisions as refugees sought protection within larger ethnic enclaves. The Lin Shuangwen Rebellion in 1786 engulfed the island and took two years to suppress. A few families rose out of the struggles of this intermediate period to form an island-wide elite that controlled the trade in the major export commodities. The third stage (1863–1895) was marked by the growth of cities and the conflict between occupational groups.

Various incidents between China and foreign powers, including Japan, raised concerns about Taiwan's sovereignty. The imperial court granted the island provincial status in 1886, and strenuous efforts were made to develop the infrastructure and defensive capabilities. Taiwan was ceded to Japan after China's defeat in the Sino-Japanese War in 1895. Communication with the mainland was cut off, and Taiwan was incorporated into the Japanese Empire as a supplier of grain and sugar and a consumer of manufactured goods. Japan brought order and peace to the island at the cost of political and economic subjugation. While rice yields outpaced population growth, per capita consumption of rice decreased. Taiwan became a nation of sweet potato eaters, and the sweet potato became a symbol of the hardships the people suffered under colonial rule.

Japan's defeat in World War II led to the return of Taiwan to China. The Taiwanese were hopeful about the new political relationship but soon were disappointed. After losing in the Chinese Civil War, the Nationalists (Guomindang [KMT]) were concerned about the security of their future island refuge and imposed severe restrictions on the population. An incident in 1947 erupted into an islandwide demonstration against Nationalist rule. The Nationalists killed thousands and wiped out the Taiwanese leadership. Forty years of martial law and authoritarian rule followed. The repressive regimes of Japan and China helped forge a common identity from multiple identities based on homeland, religious sect, and surname group.

The Korean War (1950–1953) made clear to the United States the significant role of Taiwan as a model of capitalist development and a military bulwark against socialist expansion. The country experienced a forty-year period of phenomenal economic growth based on the production and exportation of light consumer goods, but this came at the cost of political oppression, including unlawful detentions, torture, and murder.

In 1975, Chiang Kai-shek died and Taiwan lost its seat in the United Nations. In 1977, an antigovernment riot in Chungli sent a message to the KMT that it had to relax its control of society. In 1978, the KMT's dream of retaking the mainland was shattered when the United States recognized the PRC and closed its embassy in Taipei. Other countries followed suit, leaving Taiwan in international limbo. In that year, President Chiang Ching-Kuo, Chiang Kai-shek's son, set in motion a series of reforms that resulted in the lifting of martial law in 1987 and emergency rule in 1991. The reforms also included the Taiwanization of the KMT. Lee Tenghui won the first national presidential election in 1996. Lee has played the independence card to the chagrin of the mainland and KMT stalwarts, who broke away from the KMT to form their own party (New Party).

A three-party race in the 2000 presidential elections resulted in the election of the main opposition party's (the Democratic Progressive Party—DPP) candidate and former mayor of Taipei, Chen Shuibian. Elected with only 39 percent of the vote, Chen and the DPP must carry on the difficult role of governing and negotiating with the PRC. Chen Shuibian's election symbolizes the determination of the people to control their own destiny.

National Identity. The DPP rise to power has signaled an end to the KMT's futile effort to forge a common Chinese national identity through its control of government, education, and the media. The project was doomed from the start as long as China remained divided and Taiwanese were free to participate in the postwar economic boom that fueled a revival of their own culture and identity. Taiwan's national identity remains an open question.

Ethnic Relations. In spite of their cultural and linguistic differences, aborigines have found a common cause in their struggle for land rights and self-determination. The Alliance of Taiwan Aborigines (ATA) was founded in 1985. In 1988, the ATA issued a Manifesto of the Rights of the Taiwan Aborigines, and in 1991, it established the Taiwan Aboriginal Autonomous Area Assembly, a failed attempt at self-government. In 1994, President Lee Teng-hui met with aboriginal leaders to discuss their demands but rejected self-government. In 1996, the Legislative Yuan established an Aboriginal Affairs Commission chaired by a Paiwan leader from the National Assembly. The aborigines continue to press for self-government in their struggle for recognition and a place in society. Mainlander-Taiwanese tensions continue to exist but have been ameliorated by a broad dispersal of economic and political power as democracy takes root.

Today little animosity exists among Hokkien Taiwanese, but Hakka-speaking Taiwanese, who are originally from eastern Guangdong Province, have maintained a separate identity and political voice.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

According to tradition, the landscape includes imaginary flows of cosmic energy ( qi ). The divination practice of fengshui taps into pools of qi that are concentrated at points ( xue ) in the landscape. The proper location and orientation of a house or grave can bring a family good fortune. Charms strategically placed in the house also achieve this end, as do the characters for longevity, happiness, and prosperity that are carved into wood screens and windows or painted on paper to adorn interior walls.

Good fortune also is tied to the moral order of the family, and the building plan of the traditional country house reflects and reinforces that order. The relative statuses of the different generations are evident in the floor plan and dimensions of a building and its rooms. At the center of a home is the all-purpose main hall where the family rests, eats, and receives guests, and that contains the family altars, ancestral tablets, and god. On both sides of the main hall are bedrooms. The parents occupy the room immediately to the left, and the oldest son and his wife the one to the right. Unmarried children sleep in

A busy street in downtown Taipei, Taiwan. Taiwan is the second most densely populated country in the world.

the outermost rooms on each side, usually separated by sex. After the marriage of the second son, wings are built perpendicular to the main house, creating the U shape found not only in domestic architecture but also in palace and temple construction.

Towns and cities have the yanglou, a foreign-style town house in which hierarchical elements are arranged vertically instead of horizontally; stories instead of wings are added as the family expands. On commercial streets, the ground floor is the family shop and the domestic quarters are upstairs. During the heyday of rural industry in the 1980s, family-operated workshops were located on the ground floor and whole streets became production lines.

Urban architecture, especially in Taipei, is a mix of the classical, modern, and postmodern. There are walled single-story residences and temples, such as the Lungshan and Hsingtien temples, in the city's older quarters. A Western-Japanese hybrid architecture from the Japanese colonial period is found in the Presidential Office Building and National Taiwan University. The cantilevered concrete boxes and plate glass windows of the Taipei Fine Arts Museum and the corporate modernism of the Taipei World Trade Center express varying forms of modernity. The steel, concrete, and glass edifices that face Tunhwa Road are typical of the world's major metropolitan centers. The new Taipei Railway Station is a postmodern mix of classic and modern forms, a geometric concrete structure covered by a massive ceramic-tiled roof.

The KMT has inscribed its political ideology on the urban landscape. Every city has a Sun Yat-sen memorial and a Chungshan Road. The names of major avenues echo the philosophy of Confucius and Sun Yat-Sen, with names such as Jenai Lu (Benevolence Road) and Hoping Lu (Peace Road). As the claimant to China's political and cultural heritage, the KMT has built in a grandiose classical style. The Ming-style Chiang Kai-shek Memorial with its distinctive blue-tiled roof and the new opera and concert halls occupy a common plaza in downtown Taipei that rivals Beijing's Forbidden City in scale.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Food brings people together, and the eating and exchange of food define social groups. The family is identified as people who eat together, and dinner is a secular ritual that reinforces family relationships. Sharing food in the home signifies equality, and people of higher rank are never invited to dine in one's home. Larger groups of kin, neighbors, and temple members come together less frequently to share meals and reinforce their social connections.

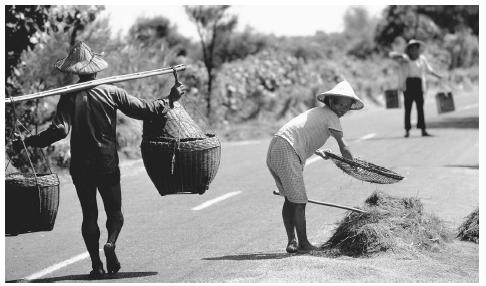

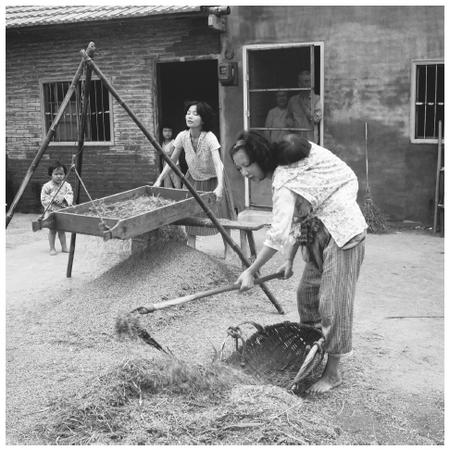

Farm workers carrying and sifting rice on a street in Taiwan. Rice is a major agricultural product.

Taiwan is a country of fish eaters. Food is cooked slowly in soups and stews or quickly by deep frying. Favorite dishes include oysters with black bean sauce, prawns wrapped in seaweed, abalone, cucumber crab rolls, and clam and winter melon soup. Small restaurants display fresh produce on the street so that customers can choose their evening meal. Fruit drinks are prepared in special beverage shops. Prosperity has produced a business culture that stresses entertaining, which supports restaurants that offer food from all the culinary regions of China. Western influences are found in bakeries and coffee shops in towns and cities. Buddhist food restrictions have produced a vegetarian cuisine in which bean curd, wheat gluten, and mushrooms are transformed into renditions of standard cuisine, sometimes being molded into the shape of ducks, chickens, and fish.

Taiwan is famous for tea, especially the lightly roasted oolong tea. Teahouses exist in almost every town, and most households have a tea cart to serve guests. Tea is brewed in a small pot and served in one-ounce cups. It is considered stimulating, conducive to conversation, and beneficial to health.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Food is served as offerings to gods, ancestors, and ghosts. A cup of tea or wine is placed on the family altar for the ancestors and gods, along with incense. More elaborate offerings are made on special days, including New Year's, gods' birthdays, and the Ghost Festival. Food offerings to ancestors are made in the form of a family dinner with seasoned dishes and rice. The altar table is set with chopsticks, bowls, soup spoons, soy sauce, vinegar, and condiments. The gods are offered cooked but not seasoned or sliced meats. Ghosts are offered cooked meals, but outside the house, where one would feed beggars.

Basic Economy. The Taiwanese have long been traders. Before the first Han settlers arrived, aborigines traded dried deer meat and hides with Chinese and Japanese merchants. When the Dutch arrived at the beginning of the seventeenth century, they developed markets in grain and sugar. In the second half of the nineteenth century, camphor and tea became major exports. The Japanese developed the island's economic infrastructure and agricultural capacity, making Taiwan a major producer and exporter of sugar. During World War II, the Japanese began to industrialize Taiwan, but this initiative was cut short by the bombing that destroyed a large portion of the island's industry and transportation infrastructure. Significant amounts of U.S. aid were received in the postwar years. The government used that money to develop key industries, especially petrochemicals, which produced human-made raw materials such as plastic. When U.S. aid was phased out in the early 1960s, the government was forced to find other sources of revenue. After a brief period of import substitution that allowed the building of industries, the government encouraged export production, which could utilize the cheap and educated labor force. Japan's large trading companies provided second hand machinery to manufacturers. The Cold War sharply divided world markets, and both Japan and Taiwan benefitted from their close connection to the U.S. market. Real growth in the gross domestic product (GDP) averaged over 9 percent per year between 1952 and 1980. In that period, Taiwan transformed itself from an agrarian economy in which farming constituted 35 percent of GDP in 1952 to an industrial economy in which industry accounted for by 35 percent of GDP and agriculture. Taiwan's 1997 GDP made it the twentieth largest economy in the world. The real motor of expansion has been accounted for by small and mediums size companies, which in 1998 made up over 98 percent of all companies, 75-80 percent of employment, and was responsible for 47 percent of economic production.

Land Tenure and Property. The country's indigenous people hunted and gathered for food and cultivated slash-and-burn plots. Neither practice encouraged permanent forms of property. Chinese immigrant farmers regarded fallow plots as unproductive wasteland and worked out arrangements for their use with aboriginal leaders, to whom they paid a nominal fee. Land tenure evolved into a three-tier system of patent holder, landowner, and tenant. The patent holder held the subsurface rights, or "bones," of the field in "perpetuity"; the landowner owned the surface rights, or "skin," of the field; and the tenant worked the field. One of the first programs instituted by the Japanese was land reform that made the landowner the sole owner. The Nationalists reduced taxes and returned land to the tiller. Today, full rights to private property are protected by the constitution.

Commercial Activities. Taiwan has a modern market economy with a large service sector, which comprises two-thirds of GDP. In July 2000, the Taipei Stock Exchange Corporation listed 473 companies with a total capitalization of NT $910 billion (U.S. $30.33 billion). The exchange rate for the New Taiwanese dollar (NT$) on 23 February 2001 was NT $33 to U.S. $1.00 (NT $1.00 = U.S. $0.031).

Major Industries. The major agricultural products are pork, rice, betel nuts, sugarcane, poultry, shrimp, and eel. The major industries are electronics, textiles, chemicals, clothing, food processing, plywood, sugar milling, cement, shipbuilding, and petroleum refining.

Trade. In 1997, the major exports were electronics and computer products, textile products, basic metals, and plastic and rubber products. The United States, Hong Kong (including indirect trade with the PRC), and Japan account for 60 percent of exports, and the United States and Japan provide over half the imports. The country also exports capital to Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Vietnam. Taiwan has become a major investor in China. In the year 2000, 250,000 Taiwanese worked on the mainland in forty-thousand companies owned or partly owned by Taiwanese, representing an investment of $40 billion (U.S.) and accounting for 12 percent of China's export earnings.

Division of Labor. In 1991, the seven major urban occupational classifications were (1) Professional, technical, and administrative (32 percent), such as teachers, physicians, engineers, architects, artists, actors, accountants, reporters, managers, and government officials; (2) large business owners (20 percent) and private business firms employing ten or more people; (3) lower white-collar clerical employees (12 percent) such as clerks, secretaries, sales personnel, and bookkeepers; (4) small business owners (24 percent) of firms employing fewer than ten workers; (5) skilled blue-collar workers (6 percent) such as carpenters, auto mechanics, electricians, lathe operators, printers, shoemakers, tailors, ironworkers, textile workers, and drivers; (6) farmers (1 percent); and (7) semi skilled and unskilled blue-collar workers (7 percent) such as a bricklayers, cooks, factory workers, construction workers, railroad firemen, janitors, laborers, street cleaners, temple keepers, barbers, security guards, police officers, and masseurs.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. The class system includes the chronically unemployed poor, beggars, and the underworld; the upper and lower bourgeoisie; and the working and middle classes. The upper bourgeoisie constitutes 5 percent of the population and include high-ranking government officials, officials who run large state-owned companies, and the owners of companies that employ more than two hundred people. The petty bourgeoisie makes up half the population and includes farmers, small

A family rides a motorcycle in Taipei, Taiwan, which is a common mode of transportation.

businesspeople, and artisans. The working class makes up a fifth of the population, and the middle class another fifth. The middle class is composed of more educated persons who engaged in nonmanual work in government, education, the military, and large companies. In the past, class coincided with ethnic group. Mainlanders constituted the bulk of the upper bourgeoisie and the middle class, and Taiwanese and aborigines accounted for most of the chronically poor, the working class, and the lower bourgeoisie. However, Taiwan's economic miracle and the Taiwanization of the government have lifted many residents into the upper bourgeoisie and the middle class.

Symbols of Social Stratification. Taiwan is a modern consumer society in which status is measured by wealth and marked by the commodities one can afford to buy, such as automobiles, clothes, and homes, as well as one's lifestyle. A person can live very cheaply in the countryside in a modest apartment, buying produce from an outdoor market, eating at street stands, and transporting a family of five on a scooter. One also can own a large condominium on a prestigious avenue in Taipei, eat in expensive restaurants, wear Western brand-name clothes, and ride in cabs or a chauffeured Mercedes.

Political Life

Government. The territory of the ROC includes the islands of Taiwan, Kinmen, Matsu, and the Penghus (Pescadores), along with several smaller islands. Taiwan and the Penghu Islands are administered together as the Province of Taiwan. Kinmen, Matsu, and the smaller nearby islands are administered by the government as counties of Fujian Province. The seat of the provincial government is in central Taiwan. The two largest cities, Taipei and Kaohsiung, are centrally administered municipalities. In 1998, the legislative Yuan eliminated the position of governor and many other administrative functions of the Taiwan Provincial Government.

From 1949 to 1991, the ROC on Taiwan claimed to be the sole legitimate government of all of China, and the Nationalists (KMT) reestablished on the island the full state apparatus that had existed on the mainland. The first National Assembly was elected on the mainland in 1947. Because elections were no longer possible on the mainland, representatives of mainland constituencies held their seats for nearly forty-five years. In 1991, the Council of Grand Justices mandated the retirement of all members of the National Assembly who had been elected in 1947 and 1948.

The second National Assembly, which was elected in 1991, amended the constitution to allow for the direct election of the president and vice president. The president is both the political leader and the commander in chief of the armed forces and presides over the five administrative branches, or Yuan: executive, legislative, control, judicial, and examination. The legislative Yuan is the main lawmaking body; its members are elected directly by the people and serve three-year terms. The control Yuan oversees public servants and investigates corruption. The twenty-nine control Yuan members are appointed by the president and approved by the National Assembly; they serve six-year terms. The judicial Yuan administers the court system and includes a sixteen-member Council of Grand Justices that interprets the constitution. Grand justices are appointed by the president with the consent of the National Assembly and serve nine-year terms. The examination Yuan recruits and manages the civil service through the Ministry of Examination and the Ministry of Personnel.

Leadership and Political Officials. Before 1987, Taiwan had a one-party system with the KMT firmly in control. Although "outside the party" candidates sometimes won local elections, opposition parties were banned. Mainlanders dominated the government at the upper level and controlled the lower level of local Taiwanese leaders through a patronage system. To ensure that no leader or faction became too strong, the KMT supported rivalries between local leaders and factions. Vote buying was prevalent.

In the 1998 elections, the DPP won 31 percent of the 176 seats and the KMT won 55 percent. In other elections, the DPP won twelve of the twenty-three county magistrate and city mayor contests compared to the KMT's eight. Aboriginal representatives hold six reserved seats in the National Assembly and the legislative Yuan. The chairman of the Aboriginal Affairs Commission is an aborigine, as is the magistrate of Taitung County. An increasing number of women are involved in politics, and some hold key positions. Women sit in the cabinet and head several agencies and commissions, and three women are members of the KMT's Central Standing Committee. A fifth of legislative Yuan and National Assembly members and two of twenty-nine control Yuan members are women.

Social Problems and Control. In 1990, the most serious social problems were juvenile delinquency, transportation, public security, environmental pollution, vice and prostitution, bribery, speculation, the poor-rich discrepancy, rising prices, and gambling. Juvenile crime tripled between 1980 and

Small and medium companies account for 98 percent of all businesses in Taiwan.

1995. In 1995, over a third of drug-related offenses were committed by youth, prompting the government to declare a war on drugs. The rise in juvenile delinquency has been attributed to the deterioration of the family system and the competitive education system. Fathers spend more time away from the home, and single-parent homes have increased. Many fifteen-year-olds have nowhere to go after finishing their nine years of compulsory education. Petty crime, drug dependency and suicides have risen dramatically in this age group.

Affluence has transformed Taiwan from a country of scooters to one of automobiles, creating traffic congestion and air pollution in the cities and a high death toll on the highways.

Murder, rape, robbery, and other violent crimes have doubled in the last ten years. Organized crime is involved in extortion, kidnaping, murder, fixing bids for public works, and gunrunning. The 1997 slaying of a prominent opposition feminist underscored the fact that 54 percent of the victims of violent crime that year were women. In 1992, 225,500 women were engaged in prostitution, including 61,400 teenagers.

Authoritarian rule in the past led to many human rights abuses. A 1997 reform has strengthened human rights protections in several ways. Prosecutors and police officers must release suspects within twenty-four hours unless a warrant is obtained from a court. Also, suspects must be informed of their right to remain silent, lawyers may be present during interrogation, and overnight interrogation is prohibited. The Council of Grand Justices has eliminated restrictions on freedom of association.

The judicial system has three levels: district courts, high courts, and the supreme court. District courts hear civil and criminal cases, high courts hear appeals, and the supreme court reviews judgments by lower courts. Criminal cases that involve rebellion, treason, and offenses against friendly relations with foreign states are handled by the high court.

Many social problems stem from lax enforcement of strict legal code. Business licenses are difficult to obtain, but once they are gotten, there is little monitoring of business. Companies, both legal and illegal, easily skirt tax, labor, environmental protection, and zoning laws. Thousands of businesses operate underground in an informal economy that may account for 25-50 percent of the GDP. Social order is maintained through personal connections and informal relationships in which the sanctions of face apply. However, this "Confucian" order requires enforcement, and businesses rely on gangsters to collect debts and enforce agreements.

Military Activity. Throughout the Chiang years (1949–1988), the KMT was fixated on retaking the mainland and maintaining its large military force that was partly sponsored by the United States. In 1979, Taiwan and the United States signed the Taiwan Relations Act, which defined the country's military mission as primarily a defensive one against the PRC and banned the sale of offensive weapons such as submarines, missiles, and bombers to Taiwan. The country maintains a large military force of 376,000 active and 1,657,000 reserve personnel. The People's Liberation Army (PLA) of China has deployed hundreds of short-range ballistic missiles on the mainland opposite Taiwan and in 1996, during the presidential election campaign, "test" fired several missiles outside the harbors of the two largest ports. This demonstration produced the intended effect on Taiwan's export-dependent economy as the stock market fell and large sums of money left the island. The latest PLA threat is electronic and informational warfare, which is aimed at over-loading and jamming the country's communications systems.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

The family has long provided welfare services to its older members. Letting the elderly live by themselves was considered unconscionable, and brothers often looked after their aging parents on a rotating basis. Older family members provided useful services such as looking after children and house sitting. While families continue to be responsible for the aged, there are holes in the system. In 1997, one third of the population sixty-five years old and above did not receive assistance from their children, 10 percent lived alone, and one-quarter experienced economic difficulties. Benevolent homes provide care for people over seventy years old. The state also provides some home care and day care services. Since 1950, labor laws have mandated that companies provide labor insurance, but this applies only to companies that employ more than fifteen workers, leaving a majority of workers unprotected.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

Taiwan participates in few international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), but the recent change in government has opened the way for more involvement. The government views working with NGOs as an alternative to being a member of the United Nations or having full diplomatic relations with most countries. Eighty-one Taiwanese NGOS aid children, teenagers, women, the handicapped, and aboriginal organizations. Human rights NGOs include the Taipei Women's Resource Foundation, the Garden of Hope Foundation, and the Taiwanese Foundation for Human Rights. After a devastating earthquake in 1999, the country received aid from several world relief agencies. Taiwanese disaster relief organizations include the Overseas Aid Council of Taiwan, World Vision Taiwan, the Tzu-chi Compassion Relief Foundation (Buddhist), the Red Cross of ROC, and the Eden Social Welfare Foundation (Christian).

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. A universal educational system and a modern industrial economy have not changed the nation's patriarchal culture. Although women work in every industry, they tend to have poorly paid menial jobs. In the office, they occupy the lower tier of managerial jobs. Women's wages and salaries are generally lower than men's and women earn only 72 percent of men's income for equivalent work. In the heyday of

Fish is the primary food consumed in Taiwan.

rural industry, factories accommodated young mothers by bringing work to their homes. Some women run their own businesses and occupy positions of power in the government.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Filial piety, fraternal loyalty, lineage solidarity, and family are the pillars of this patriarchal society. Although women were vital to the reproduction of the patrilineage, that role translated into few rights for women. However, the domestic notions of prosperity, happiness, and peace constituted a parallel set of values that was tied to household productivity and well-being. Insofar as women's hard work and organizing skills contributed to a household's prosperity, women gained respect in the home. Women's organizing skills and adeptness at relationship building have to been important assets in small-scale industries, in which many successful women manage businesses and supervise workers in small factories and workshops. The network building required in the rural and export industries has favored relationships with relatives on both sides of the family, increasing the importance of women. Women have gone to college and joined professional ranks, and some have entered politics. Recent trends reflect an increase in women's power and status, such as delayed marriages, higher divorce rates, fewer children, and higher educational attainment among women. A growing feminist movement actively promotes women's rights. Legislation has been enacted that recognizes women's rights to child custody and inheritance of property. However, men continue to hold most material wealth and political power and strongly resist the women's movement. Women leaders have been vilified and jailed.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Historically, there were three ways to marry. Major marriage was the standard and most common form. It was an arrangement between families involving the use of a matchmaker. Often, the bride and groom met for the first time on the day of the wedding. Each family would sponsor its own wedding feasts on different days. Both a brideprice and a dowry were exchanged. The wife left her natal family to take up residence in her father-in-law's household. The second most common form of marriage was called sim pua. It involved adopting an infant girl and raising her as daughter and future daughter-in-law. Although this form was affordable for poorer families, it was also the choice of mothers because it allowed them exercise authority over their daughters and daughter-in-law from an early age. Often this meant that the adopted daughter was treated very poorly. Minor marriages were the type of marriage most likely to end in divorce. The third form of marriage was uxorilocal marriage, which involved a man marrying into his wife's family. The groom entered into to this form because he had no property, and the bride because her family had no male heir. Sim pua and uxorilocal marriages are far less common today. Young men and women now have more of a say about who they want to marry but still need their parents' blessings and the mediation of a matchmaker.

Domestic Unit. The ideal family type is the grand or joint family, a multigenerational family that includes a father, a mother, single children, and married brothers and their families living together under one roof. However, for this form of family to succeed, it must be wealthy and have a strong patriarch, diverse business interests, compliant daughters-in-law, and lineage support. The most common family unit is the stem family, consisting of the parents and a married son, a daughter-in-law, and their children. In a modern society, increased opportunities for employment outside the family and village, larger incomes, and universal education have favored smaller households. Nuclear families have become more common as the role of the family as a productive unit has diminished.

Inheritance. In spite of amendments to the constitution that guarantee equal rights of inheritance for women, men inherit most property, especially land. In this patrilineal society, property is a male birthright. Traditionally, the property a woman inherited was obtained at her marriage, in the form of a dowry, when she left her family. Also, at that time women inherited pocket money that was theirs to spend.

Kin Groups. After the family, the most important kin group used to be the surname group. Historically, in a frontier society, the surname group was an important source of security and protection. Many surname groups were made up of the broken remnants of lineages that were casualties of clan wars on the mainland. Members of surname groups might not have been able to demonstrate a genealogical connection, but they shared a name and could point to a common place of origin on the mainland; this constituted sufficient criteria to claim a blood tie. Most surname groups worshiped a common god and centered their collective activities at temples. The modern state has replaced many of the functions of the surname group.

Socialization

Infant Care. Infants and small children sleep with their mothers and are fed on demand. They are carried and entertained by adults and older children. Weaning is done abruptly at about age two. Little is expected of young children, who are seldom punished. By the time they begin primary school, children start doing chores. Girls help care for younger siblings and do household tasks, and boys run errands. Children are expected to be obedient, avoid fighting, and work hard. Threats and scolding are used to discipline children, but physical punishment is rare. Rewards also are used to motivate children. The mother is primarily responsible for child care, and the mother-child relationship is usually close. Fathers play with younger children and punish children for misbehavior; their aloofness often causes children to fear their fathers. Girls generally are treated more strictly than boys, but fathers often are more affectionate toward their daughters.

Child Rearing and Education. The Japanese instituted a system of universal primary education for grades one through six. The Nationalists extended the educational system to the ninth grade in 1968 and made it compulsory in 1982. In 1993,

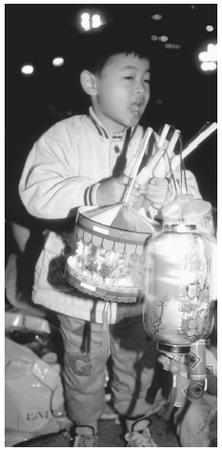

A boy holds onto a handful of lanterns for celebrating the New Year Lantern Festival at Chiang Kaishek Memorial in Taipei, Taiwan.

they extended free education to the twelfth grade. In 1997, about 90 percent of junior high graduates continued their studies in a senior high school or a vocational school. Children enter kindergarten at age six. After junior high school (grade nine), students take a competitive examination to determine the school they will attend. There are three routes: an academic high school, a secondary vocational school, or a vocational junior college.

Higher Education. The academic route leads to the best colleges and universities, of which National Taiwan University is the most prestigious. There are over one hundred institutions of higher learning, which admit sixty thousand students a year. For graduate education, many students go abroad, including thirteen thousand who study in the United States each year. The premier research institution is the Academia Sinica.

Etiquette

Because social relationships and the cultivation of social relationships are considered important, Taiwanese people are friendly and courteous. Social relationships derive importance from the belief that one cannot do anything alone and everyone requires the help and cooperation of others. The exchange of cigarettes, business cards, or small gifts is a quick and easy way to overcome initial shyness in forming a personal connection. Introductions are important in initiating a relationship. One's name and reputation have currency, as is demonstrated by the exchanging of business cards. Initial friendliness is only an overture to friendship and can quickly turn cold if one's intentions are suspected. As cordial as Taiwanese can be in a personal setting, on the street with strangers, it is a free-for-all; one fights for every inch of space on the streets of Taipei, and holding one's place in a line is a contest. It takes time to build relationships of trust. Teahouses, restaurants, and homes are places where people cultivate relationships. The object of these encounters is to relax, let down one's guard, and connect in a genuine and open way. Although people are interested in friendship, they understand that friendship has utilitarian benefits, as friends are expected do each other favors and help each other get things done. In spite of their openness and friendly demeanor, people pay close attention to status and authority as defined by age, education, occupation, and gender. Although it is difficult for people of different statuses to be friends, they still can form a relationship of mutual benefit ( guanxi ). Much of the work of government and business gets done through these relationships.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Most of the people are followers of China's three religious traditions; Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, collectively referred to as the "three teachings," or sanjiao. Each religion has a long history and its own temples, priests, and sacred texts. Although the elite make distinctions between the sanjiao, most people practice a syncretic blend referred to as popular or folk religion. Popular religion includes elements of these three sets of teachings, along with beliefs in ancestors, ghosts, magic, and the efficacy of religious mediums. Popular religion is based on localized cults of nearly two hundred gods. The cults are centered in thousands of temples throughout the island. Many of the gods were originally historical figures who founded communities in Fujian during the Song Dynasty and were brought to Taiwan by Han immigrants. The gods were a source of magical power, or ling, which could be tapped through ritual. They were also the focal point of the community, bringing people together to form new social groupings. If families left to form a new community, they brought a newly carved statue of their god with them. In a ritual called dividing incense ( fenxiang, ) they formed a new temple, which remained linked to the mother temple. On a god's birthday, pilgrims pay their respects to the temples from which their own temples are descended. Through their travel, they retrace their region's history and reconfirm their subethnic ties. Rural industrialization brought prosperity to many communities, which rebuilt their temples or constructed new ones. The gods continue to play a role in mediating community and regional relationships in an industrial society.

Two percent of the population is Protestant. The Canadian Presbyterian missionary George Leslie MacKay came to the country in the 1870s and established sixty churches and trained native missionaries until the Japanese undid much of his work. Protestantism has remained strong among the aborigines and Hakka. In the postwar period, Taiwanese Protestant leaders played a leading role in the opposition movement for human rights and democracy and suffered the consequences of defying the government's authority with detention, prison, and self-exile.

Rapid modernization has spawned many new religions, which have their roots in popular religion but address the social and psychological dislocations caused by modernity. One popular new religion, Yiguandao, states that the Maitreya Buddha has returned to the world to spread the Tao and save the world from destruction.

Religious Practitioners. Each of the three great religions has priests who are responsible for observing the religious calendar and carrying out the prescribed rituals. The most colorful are the spirit mediums tongqi. Gods possess a tongqi and through him or her communicate to cult followers verbally or in the form of "spirit writing." The tongqi also dispenses charms in response to personal requests for aid, holding office hours certain days of the week.

Rituals and Holy Places. The gods are honored on their birthdays in a public demonstration of popular religion. The gods are brought out of their temples and paraded down the streets in elaborately carved palanquins rolled along by four men. Two men carry a litter on which the god's spirit descends violently, shaking and rocking the chair. The procession is led by the tongqi who falls into a trance while possessed by the god's spirit and practices self-mortification, by piercing his cheek with a skewer, slashing his chest with a sword, or banging his forehead with a ball of nails. The entourage visits each follower's household, which displays an offering of food on a table outside the front gate. Afterward, tables are set up in the street and a banquet is held for all temple members. The more faithful go on a pilgrimage that includes visits to other temples dedicated to their god and eventually arrive at the god's home temple, which usually is in the south, where the first immigrants arrived. The birthday of Mazu, Taiwan's most popular god, is celebrated on 23 May.

The main ritual honoring ancestors occurs during the Qingming festival on 5 and 6 April. Family members gather and visit the graves of their ancestors to burn offerings of paper money and incense. The offerings are preceded by a flurry of activity to clear the overgrown gravesite. The Ghost Festival on 15 July is a three-day affair in which ghosts of all stripes are propitiated. The 15 August Mid-Autumn Festival rounds out the ceremonial calendar as families worship the moon god and ask for protection, fortune, and family unity.

Death and Afterlife. Taiwanese believe in the Buddhist heaven and hell and reincarnation. A good life is rewarded in heaven, and a bad life in hell, before reincarnation. A person's fate is determined by past lives. One can improve one's fortunes after death by performing good deeds while one is alive. Through special prayers and offerings, the living can improve the afterworld conditions of the deceased and their chances in the afterlife.

Medicine and Health Care

Taiwan has a legacy of both Western and Chinese medicine. The missionary George MacKay opened a clinic in the northern port of Tan-shui in 1880, treating patients and training indigenous practitioners in Western medical science. In the colonial period, the Japanese implemented an islandwide program of public health and sanitation, that brought under control infectious diseases such as cholera, smallpox, and bubonic plague. They also built a Western hospital and medical college in Taipei and charity hospitals and treatment centers around the island. Medicine became one of the only professional occupations open to the Taiwanese. Today the National Health Insurance program covers all citizens and provides free medical care for children up to four years old and people over seventy.

Chinese medicine also is practiced. It is a system of health care based on ancient Chinese philosophy and thousands of years of clinical practice. Traditional doctors understand the body in terms of dynamic forces and consider each patient's illness unique. Examination of the patient's pulse and tongue is the principal diagnostic tool. Doctors also consider weather conditions and the patient's emotional state. Sickness is regarded as the result of a disturbance in the polarity of one or more of the body's systems that affects the flow of qi, or life force. Doctors prescribe a concoction of herbs and other natural pharmaceuticals to reset the polarity or use acupuncture to adjust the flow of qi.

Secular Celebrations

Traditional Chinese festivals mark an agricultural cycle based on the lunar calendar. The first day of Chinese New Year, called the Spring Festival ( Chunjie ), is the most important festival. Families whose members are dispersed throughout the island usually come home to celebrate it. The night before New Year's Day is devoted to feasting. Parents give their children red envelopes with money inside. On New Year's Day, the family pays its respect to ancestors, gods, and elders. It visits the local temple to worship and burn incense, followed by visit to friends. The fifteenth and last day of the New Year celebrations is the Lantern Festival ( yuanxiaojie ). Children carry lanterns to the temple, watch fireworks, and eat round dumplings ( yuanxiao ), a symbol of unity. The Dragon Boat Festival (7 May), or Poets' Festival, commemorates the poet Ch'u Yuan, who threw himself into a river after an altercation with the emperor. Glutinous rice cakes are thrown into the water to prevent sea creatures from eating the poet's body.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. The arts have not received general support in this poor and politically

In Taiwan, women earn only 72 percent of men's income for equivalent work.

oppressed country, and some of the most prominent painters and writers have been imprisoned and killed. During the Japanese era (1895–1945), Taiwanese painters studied at the Tokyo Fine Arts Institute and showed their work at annual exhibitions in Taipei. In the postwar period, the U.S. Information Service provided one of the first public spaces for fine arts, to promote Western-style modern art. A National Arts Academy was established in 1982, and a year later the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, the country's first museum of modern art, opened. At that time, the Ministry of Culture and the Council for Cultural Planning and Development began to sponsor native and international exhibitions. The 1980s witnessed a surge in art collecting and a proliferation of art galleries. Literary magazines have been a source of support for writers and were a forum for lively debates throughout the Japanese and Nationalist periods. In the mid-1970s, newspapers began to sponsor annual fiction contests.

Literature. Living in Japan in the 1920s, the first generation of modern Taiwanese writers wrote in Japanese, embraced modernity, and denounced China's cultural heritage. This generation of authors included Lai He (1894–1943), the father of the Taiwanese New Culture Movement and the founder of the magazine Taiwanese New Literature. The next decade saw the younger generation of writers react against modernism, which had become identified with Japanese colonialism. The chief spokesman in the Nativist Literary debate was Huang Shih-hui, who advocated a class-oriented perspective and the of vernacular language to express a national consciousness. Beginning in the 1930s, the Nativist movement suffered under the general crackdown on leftists by the Japanese and later the Nationalists. The 1960s modernist fiction writers Pai Hsienyung and Wang Wen-hsing wrote about the conflict between bourgeois individualism and filial piety. Ch'en Ying-chen wrote about the lives of native Taiwanese and the hardships they experienced under the Japanese and the KMT, presaging the modernist-nativist literary debates that raged in the 1970s. Interest in modernist and nativist writers declined in the late 1970s and 1980s as the new urban middle class found their work too formal or too political. Writers in the 1980s and 1990s experimented with postmodern literary forms and more eclectic subject matter, including sexual liberation, political complacency, and corporate life.

Graphic Arts. During the Japanese era, painters were influenced by Impressionism and painted native scenes in oils. After World War II, the Nationalists revived classic Chinese ink painting and persecuted nativist painters, including Taiwan's best known painter at the time, Chen Cheng-po. Li Chung-sheng was a pioneer of abstract painting in the 1950s. Other modernist movements, such as surrealism, dadaism, pop art, minimalism, and op art, influenced artists in the 1960s and 1970s. A new nativist movement ( xiangtu ) emerged in the late 1960s with the work of Hsi Te-chin, who painted local scenery and architecture and experimented with folk art. The lifting of martial law in 1987 generated a second wave of nativist consciousness ( bentu ), this time with an urban and modernist outlook. In the 1990s, postmodern artists explored the symbolism of the body and the tensions between individual existence and collective values.

Performance Arts. Liu Feng-hsueh introduced modern dance to Taiwan in 1967 after studying in Germany. Her work combines structured modern choreography with the movement styles of Chinese opera, martial arts, and more recently aboriginal folk dance. Lin Hwai-min was a student of Martha Graham and the founder of the Cloud Gate Dance Theater, the country's premier dance company. His dances explore Chinese and Taiwanese identity, combining modern dance techniques and Chinese opera movements. Students of Lin Hwai-min have opened their own studios, performing dances that incorporate modern dance technique with Chinese and Taiwanese narratives. The Taipei Folk Dance Theatre and the Formosan Aboriginal Song and Dance Troupe are among several new dance companies that have formed to reconstruct and preserve traditional dances.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

Continued economic prosperity is dependent on progress in telecommunications, computer, and electronic technologies. Sizable amounts of public and private resources have been mobilized toward this effort. The National Science Council is funding scientific research for fiscal year 2000. The Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI), the largest nonprofit research institute, was founded in 1973 by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and helps develop industrial technologies and transfer them to domestic private enterprises to improve their competitive position in international markets. The social sciences constitute major university departments, research institutes, associations, and organizations, including anthropology, archaeology, business and management, economics, law, political science, sociology, and women's studies.

Bibliography

Ahern, Emily. The Cult of the Dead in a Chinese Village, 1973.

——, and Hill Gates, eds. The Anthropology of Taiwanese Society, 1981.

Baity, Philip Chesley. Religion in a Chinese Town, 1975.

Cohen, Myron L. House United, House Divided: The Chinese Family in Transition, 1976.

Davidson, James W. The Island of Formosa: Past and Present, 1903, rev. ed. 1988.

Davison, Gary Marvin, and Barbara E. Reed. Culture and Customs of Taiwan, 1998.

Gallin, Bernard. Hsin Hsing, Taiwan: A Chinese Village in Change, 1966.

Gates, Hill. China's Motor: A Thousand Years of Petty Capitalism, 1996.

Gold, Thomas. State and Society in the Taiwanese Miracle, 1986.

Harrell, Stevan. Ploughshare Village: Culture and Context in Taiwan, 1974.

Ho, Samuel P. S. Economic Development of Taiwan 1860– 1970, 1978.

Hsiung, Ping-chun. Living Rooms as Factories: Class, Gender, and the Satellite Factory System in Taiwan, 1996.

Hu, Tai-li. My Mother-in-Law's Village: Rural Industrialization and Change in Taiwan, 1983.

Kerr, George H. Formosa Betrayed, 1965.

Knapp, Ronald G. China's Living Houses: Folk Beliefs, Symbols, and Household Ornamentation , 1999.

Kung, Lydia. Factory Women in Taiwan, 1978, rev. ed 1994.

Marsh, Robert M. The Great Transformation: Social Change in Taipei, Taiwan since the 1960s , 1996.

Meskill, Johanna Menzel. A Chinese Pioneer Family: The Lins of Wu-feng, Taiwan 1729–1895, 1979.

Olsen, Nancy Johnston. The Effect of Household Composition on the Child Rearing Practices of Taiwanese Families , 1971.

Pasternak, Burton. Kinship and Community in Two Chinese Villages, 1969.

Rubinstein, Murray R., ed. The Other Taiwan: 1945 to the Present, 1994.

——. Taiwan: A New History , 1999.

Sangren, P. Steven. History and Magical Power in a Chinese Community, 1987.

Seaman, Gary. Temple Organization in a Chinese Village, 1978.

Shepherd, John Robert. Statecraft and Political Economy on the Taiwan Frontier 1600–1800, 1993.

Skoggard, Ian A. The Indigenous Dynamic in Taiwan's Postwar Development: The Religious and Historical Roots of Entrepreneurship, 1996.

Thorton, Arland, and Hui-Sheng Lin, eds. Social Change and the Family in Taiwan , 1994.

Weller, Robert P. Unity and Diversities in Chinese Religion, 1987.

Winkler, Edwin A., and Susan Greenhalgh, eds. Contending Approaches to the Political Economy of Taiwan, 1990.

Wolf, Arthur, ed. Studies in Chinese Society, 1978.

Wolf, Margery. Women and Family in Rural Taiwan, 1972.