Culture of Suriname

Culture Name

Surinamese

Orientation

Identification. The name "Suriname" (Sranan, Surinam) may be of Amerindian origin. Suriname is a multiethnic, multicultural, multilingual, and multireligious country without a true national culture.

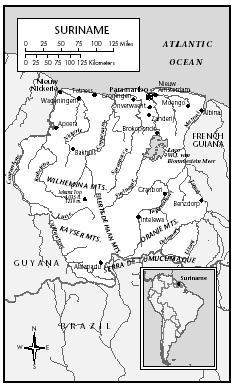

Location and Geography. Suriname is in South America but is considered a Caribbean country. The total area is 63,250 square miles (163,820 square kilometers). The majority of the inhabitants live in the narrow coastal zone. More than 90 percent of the national territory is covered by rain forest. Suriname is a tropical country with alternating dry and rainy seasons. Since the early colonial days, Paramaribo has been the capital.

Demography. The official population estimate in 2000 was 435,000. Approximately 35 to 40 percent of the population is of British Indian descent (the so-called Hindostani), 30 to 35 percent is Creole or Afro-Surinamese, 15 percent is of Javanese descent, 10 percent is Maroon (descended from runaway slaves), and there are six thousand to seven thousand Amerindians. Other minorities include Chinese and Lebanese/Syrians. Since 1870, the population has increased, but with many fluctuations. In the 1970s, mass emigration to the Netherlands led to a population decrease; an estimated 300,000 Surinamers now live in the Netherlands.

Linguistic Affiliation. The official language and medium of instruction is Dutch, but some twenty languages are spoken. The major creole language and lingua franca is Sranantongo, which developed at the plantations, where it was spoken between masters and slaves. Sranantongo is an English-based creole language that has African, Portuguese, and Dutch elements. Attempts to make Sranantongo the official language have met with resistance from the non-Creole population. Other major languages are Sarnami-Hindustani and Surinamese-Javanese. The Chinese are Hakka-speaking. The Maroon languages are all English-based. Eight Amerindian languages are spoken.

Symbolism. The major symbols of the "imagined community" are the national flag, the coat of arms, and the national anthem. The flag was unveiled at independence. It consists of bands in green, white, red, white, and green. Green is the symbol of fertility, white of justice and peace, and red of patriotism. In the center of the red band is a yellow five-pointed star that stands for national unity and a "golden future." The five points refer to the five continents and the five major population groups. The national coat of arms shows two Amerindians holding a shield and has the motto Justitia-Pietas-Fides ("Justice-Love-Fidelity"). The left part of the shield shows a ship; the palm tree on the right represents the future and is the symbol of the righteous man. The national anthem is based on a late nineteenth-century Dutch composition. In the 1950s, a text in Sranantongo was added. In the first lines, Surinamers are encouraged to rise because Sranangron (Suriname soil or territory) is calling them from wherever they originally come.

Independence Day has lost its meaning for many people because of the political and socioeconomic problems since independence. The mamio ,a patchwork quilt, is often used as an unofficial symbol of Suriname's variety of population groups and cultures. It reflects a sense of pride and a belief in interethnic cooperation. The country's potential richness and fertility are captured in the saying "If you put a stick in the ground, it will grow."

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. Suriname was a classical Caribbean plantation society. In the 1650s, English

Suriname

colonists and Sephardi Jewish refugees from Brazil introduced the cultivation of sugar. When the Dutch took over from the British in 1667, fifty sugar plantations were operating. After a decrease in the number of estates, Suriname developed into a prosperous colony producing sugar and later coffee, cacao, and cotton. In the nineteenth century, the value of these products dropped sharply, although sugar exports were more stable.

In 1788, slaves numbered fifty thousand out of a total population of fifty-five thousand, yet there were not many slave rebellions. By 1770, five thousand to six thousand Maroons or runaway slaves were living in the jungle. After waging protracted guerrilla wars, they established independent societies in the interior. Between 215,000 and 250,000 slaves were shipped to Suriname, mostly from West Africa. Slavery was not abolished until 1863. After a ten-year transition period in which ex-slaves had to perform paid work on the plantations, contract laborers from Asia were imported to replace them. Between 1873 and the end of World War I, 34,304 immigrants from British India (the Hindostani) arrived. A second flow of immigrants came from the Dutch East Indies, bringing almost 33,000 Javanese contract laborers between 1890 and 1939. The idea was that the Asian immigrants would return to their homelands as soon as their contracts had expired, but most remained.

The policy of the Dutch colonial administration was one of assimilation: Native customs, traditions, languages, and laws had to give way to Dutch language, law, and culture. The introduction of compulsory education in 1876 was an important aspect of this policy. Javanese and Hindostani traditions proved so strong, however, that in the 1930s assimilation was replaced by overt ethnic diversity. Against the will of the influential light-skinned Creole elite, the governor recognized so-called Asian marriages and other Asian cultural traditions.

The Creole elite increased its influence in the wake of a political process that started in 1942, when the Dutch promised their colonies more autonomy. The Creole slogan "Boss in our own home" expressed the prevailing feeling. Before the first general elections in 1949, number of political parties were formed, mostly on an ethnic basis. In 1954, Suriname became an autonomous part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

World War II had a profound effect on the nation's socioeconomic structure. The presence of U.S. troops to protect bauxite mines and transport routes led to an increase in employment and migration from the rural districts to Paramaribo and the mining centers. This urbanization gradually made Paramaribo a multiethnic city, and the proportion of Creoles in the urban population dwindled.

The position of the light-skinned Creole elite was challenged by the so-called fraternization policy, which involved political cooperation among nonelite Creoles and Hindostani. Creole nationalism later led to Hindostani opposition. Despite the strong resistance of the Hindostani party and the fact that the cabinet had only small majority in the parliament, a Creole-Javanese coalition led the nation to independence on 25 November 1975.

National Identity. After independence, Suriname attempted to bring about a process of integration that would transcend ethnic, social, and geographic barriers. That process was accelerated by the military regime that gained power on 25 February 1980, but lost popular backing when it committed gross violations of human rights during the socalled December murders of 1982. In 1987, the transition to democracy restored the "old political parties" to power. Race, class, and ethnicity continue to play an overwhelming role in national life.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

Greater Paramaribo, with 280,000 inhabitants, is the only city and the traditional commercial center. Paramaribo is multiethnic, but the rest of the coastal population lives in often ethnically divided villages.

Paramaribo is a three hundred-year-old colonial town with many wooden buildings in the old center. A distinctive national architectural style has developed whose most important characteristics are houses with a square brick foundation, white wooden walls, a high gabled roof, and green shutters. Multiethnicity is demonstrated by the many churches, synagogues, Hindu temples, and mosques.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. The nation's many immigrants have left culinary traces. The only truly national dish is chicken and rice. In Paramaribo, Javanese and Chinese cuisine and restaurants are popular. In the countryside, breakfast consists of rice (for the Javanese), roti (Hindostani), or bread (Creoles). The main meal is eaten at 3 P.M. , after offices have closed. After a siesta, sandwiches and leftovers are eaten. Drinking water and street food are generally safe.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. At weddings and birthday parties, especially those celebrating a jubilee year, the so-called Bigi Yari , huge amounts of food are served. In Javanese religious life, ritual meals called slametans commemorate events such as birth, circumcision, marriage, and death.

Basic Economy. Commercial agriculture is limited to the narrow alluvial coastal zone. Smallholders are mostly Javanese and Hindostani. The largest rice farms are government-owned. The country is self-sufficient in rice, some tropical fruits, and vegetables, which also are exported. In 1996, agriculture contributed 7 percent to the national economy and employed 15 percent of the workforce. There is a small fishing industry. Overall, the country is a net importer of food.

Land Tenure and Property. Provisions for collective landholding are part of the legal system. Collective holding of agricultural lands can be found among Maroons, Amerindians, and Javanese.

Commercial Activities and Major Industries. The most important sector is mining, with bauxite and gold the leading products. Most of the bauxite is processed within the country produce alumina. Alumina and aluminium account for three-fourths of exports. Gold production is difficult to estimate.

Trade. In the 1990s, the main trading partners were Norway, the United States, the Netherlands, and the Netherlands Antilles. Besides mining products, exports include rice, bananas, shrimp, and timber. Imports come mainly from the United States, the Netherlands, and Trinidad and Tobago and include capital goods, basic manufactured goods, and chemicals.

Division of Labor. More than half the labor force is employed by the state. Those jobs are officially assigned on the basis of education, experience, and competence, but unofficially, ethnicity and political affiliation often play a role.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. Classes are increasingly multiethnic as a result of the social mobility of all population groups. The class structure is based on income and, to a lesser degree, social position. The elite includes import–export merchants, entrepreneurs, politicians, and military officers. Devaluation of the currency has squeezed a traditional middle class that is dependent on fixed incomes (civil servants, pensioners, teachers, paramedics). The gap between rich and poor is widening. The Hindostani could not maintain their caste system once they left India, but some notion of caste persists.

Political Life

Government. Suriname has been an independent republic since 1975. Its political institutions are defined by the constitution of 1987. The National Assembly has fifty-one members who are elected for a five-year term by proportional representation. The president is elected by a two-thirds majority in the Assembly. The president appoints the cabinet ministers. The Council of State, chaired by the president and including representatives of the military, trade unions, business, and political parties, can veto legislation that violates the constitution.

The decorative façade of a house in a Djuka village. Commercial oil paints are applied to the wood with a length of a cut plant stem.

Leadership and Political Officials. Most political parties are based on ethnicity. Party politics are characterized by fragmentation and the frequent splitting up of parties. Since the elections of 1955, no party has had majority in the National Assembly, and so coalitions of are always necessary to form a government. Many party leaders are authoritarian. Clientelism, a patron–client relationship between a politician and voters in which the politician delivers socioeconomic assistance (e.g., jobs) in exchange for a vote, is an important feature of politics.

Social Problems and Control. The administration of justice is entrusted to a six-member Court of Justice and three cantonal courts. The crime rate has increased since the 1980s because of socioeconomic regression; crimes against property accounted for nearly 80 percent of all crimes in 1995. Formal punishments include jail sentences and fines; no death penalty has been enacted since World War II, but the law is still on the books. So far, human rights violations have not been prosecuted. Informal control is still fairly high but has eroded since a military coup in 1980.

Military Activity. The National Army played a major role in domestic (political) affairs from 1980 to 1992. It was involved in a civil war in the interior in the 1980s and in a United Nations mission in Haiti.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

There is a limited social welfare system funded by the state. Assistance by social organizations and benevolent societies to the elderly, poor, and infirm remains indispensable, as do remittances and care packages sent by emigrants.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

Labor unions traditionally play an important political role. The number and significance of human rights, women's, and social welfare organizations has grown. Suriname is a member of several major global and regional organizations.

Gender Roles and Statuses

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Official labor force figures underestimate the participation of women, many of whom are employed in the informal sector. Women also work in subsistence agriculture.

Despite the economically independent position of many women within their households, in society in general women cannot claim equal status. The domestic status of women varies. Women are the emotional and economic center of the household (matrifocality) in many Creole groups but are subordinated in traditional, patriarchal Hindostani circles.

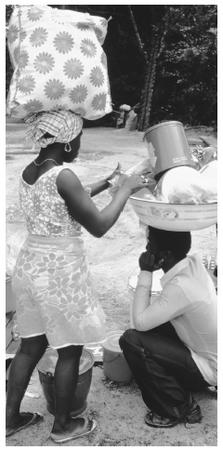

Carrying bundles balanced on the head is common in Djuka villages in Suriname.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Although many marriage partners are of the same ethnic group, mixed marriages do take place in Paramaribo. In traditional Hindostani families in the agricultural districts, parents still select partners for their children. Weddings can be very lavish. Living together without being married is common but is not acceptable to traditional Hindostani, among whom the bride is expected to be a virgin. In the Caribbean family system, female-headed households and the fact that women have children from different partners are accepted. Some women practice serial monogamy; it is more common for men to have several partners simultaneously. Having a mistress ( buitenvrouw ) is accepted and usually is not shrouded in secrecy. Maroon men often have different wives in different villages; those men do, however, have the responsibility to supply each wife with a hut, a boat, and a cleared plot for subsistence agriculture.

Domestic Unit. Domestic units vary in type, size, and composition, ranging from female-headed households to extended families. Among the Hindostani, the institution of the joint family has given way to the nuclear family, and the authority of the man is eroding.

Kin Groups. The clan system among the Maroons is based on a shared belief in a common matrilineal descent. The population of a village can overlap considerably with a matrilineal clan ( lo ).

Socialization

Infant Care. Babies usually sleep in cribs near the mother and are moved to a separate room when they are older. In the interior, mothers carry their babies during the day; at night, babies sleep in a hammock. In contrast to Maroon women, Amerindian women are reluctant to let anybody touch their babies.

Child Rearing and Education. Education and diplomas are considered exceedingly important by all population groups.

The Maroons and Amerindians have rites of passage. Among the Wayana, boys undergo an initiation rite, eputop , in which wasps are woven into a rush mat in the form of an animal that symbolizes power and courage. The mats are tied to the boys, who must withstand the stinging without a whimper. Among the Caribs, the girls undergo a similar ritual, except that stinging ants rather than wasps are used. The circumcision of Muslim boys is considered a rite of passage.

Higher Education. Despite economic constraints, public expenditure on education remains relatively high. Higher education is free. Education is compulsory between ages six and twelve. Between ages six and seventeen, school enrollment ratio is officially about 85 percent but the dropout rate is high. The adult literacy rate was 93 percent in 1995.

Paramaribo is the only city in Suriname and, as such, serves as the country's commercial center.

Etiquette

A typical, mainly urban Creole, expression is "no span" ("Keep cool; don't worry"), symbolizing the generally relaxed atmosphere. The population has a reputation for being hospitable, and most houses do not have a knocker or a bell. Shoes often are taken off when one goes inside. Guests usually are expected to partake in a meal. A casual conversation is initiated by a handshake, and good friends are greeted with a brasa (hug). Children are expected to respect adults, use the formal form of address when speaking to them, and be silent when adults speak.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. The three major religions are Hinduism, Christianity, and Islam. About 80 percent of the Hindostani are Hindus, 15 percent are Muslims, and 5 percent are Christians. Most Creoles are Christians: the largest denominations are Roman Catholicism and the Moravian Church (Evangelische Broedergemeente); the Pentecostal Church has been growing. Most Javanese are Muslims. Officially most Amerindians are baptized, as are many Maroons. However, many of these groups also adhere to their traditional religious beliefs. The most important alternative system for Maroons and Creoles is Winti, a traditional African religion that was forbidden until the 1970s.

Religious Practitioners. Religious practitioners of all beliefs are paid by the Ministry of the Interior.

Medicine and Health Care

Despite a lack of public funding, health care indicators are comparable with those in other Caribbean countries. Life expectancy at birth was 70.5 years in 1996 compared with 64.8 years in 1980. Infant mortality was 28 per 1,000 live births in 1996 (46.6 in 1980). Specialized care is available at the University Hospital in Paramaribo. There are medical posts throughout the interior. In all population groups, traditional healers are often consulted.

Secular Celebrations

Holidays include 1 January (New Year's Day), Id al-Fitr (end of Ramadan), Holi Phagwa (Hindu New Year, March/April), Good Friday and Easter Monday (March/April), 1 May (Labor Day), 1 July (Keti Koti, Emancipation Day, previously Day of Freedoms), 25 November (Independence Day), and 25–26 December (Christmas).

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. Government and private, support for the arts is virtually nonexistent. Most artists and writers are amateurs. A lack of publishers and money makes writing and selling literature a difficult enterprise. Most authors try to sell their publications to friends or on the street. The great majority of established authors live and work in the Netherlands. Oral literature has always been important to all the population groups.

Painting is the most fully developed graphic art. The most popular art form is music. Popular among Creoles are kaseko and kawina music, originally sung and played at the plantations. Among Hindostani, the songs from Hindi movies and videos are favorites. A few traditional Javanese gamelan orchestras perform traditional Javanese songs.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

The University of Suriname in Paramaribo has faculties of law, economics, medicine, and social sciences. There are also a number of technical and vocational schools.

Bibliography

Bakker, Eveline, et al., eds. Geschiedenis van Suriname: Van stam tot staat , 2nd ed., 1998.

Binnendijk, Chandra van, and Paul Faber, eds. Sranan: Cultuur in Suriname , 1992.

Bruijning, C. F. A., and J. Voorhoeve, eds. Encyclopedie van Suriname , 1978.

Buddingh', Hans. Geschiedenis van Suriname , 2nd ed., 1995.

Colchester, Marcus. Forest Politics in Suriname , 1995.

Dew, Edward M. The Difficult Flowering of Surinam: Ethnicity and Politics in a Plural Society , 1978.

Economist Intelligence Unit. Country Profile Suriname 1998–99 , 1999.

Hoefte, Rosemarijn. Suriname , 1990.

Lier, R. A. J. van. Frontier Society: A Social Analysis of the History of Surinam , 1971.

Meel, Peter. "Towards a Typology of Suriname Nationalism." New West Indian Guide 72 (3/4): 257–281, 1998.

Oostindie, Gert. Het paradijs overzee: De 'Nederlandse' Caraiben en Nederland , 1997.

Plotkin, Mark. J. Tales of a Shaman's Apprentice: An Ethnobotanist Searches for New Medicines in the Amazon Rain Forest , 1993.

Price, Richard. First-Time: The Historical Vision of an Afro-American People , 1983.

Sedoc-Dahlberg, Betty, ed. The Dutch Caribbean: Prospects for Democracy , 1990.

Szulc-Krzyzanowski, Michel, and Michiel van Kempen. Deep-Rooted Words: Ten Storytellers and Writers from Surinam (South America) , 1992.