Culture of Sudan

Culture Name

Sudanese

Alternative Names

In Arabic, it is called Jumhuriyat as-Sudan, or simply as-Sudan.

Orientation

Identification. In the Middle Ages, Arabs named the area that is present-day Sudan "Bilad al-Sudan," or "land of the black people." The north is primarily Arab Muslims, whereas the south is largely black African, and not Muslim. There is strong animosity between the two groups and each has its own culture and traditions. While there is more than one group in the south, their common dislike for the northern Arabs has proved a uniting force among these groups.

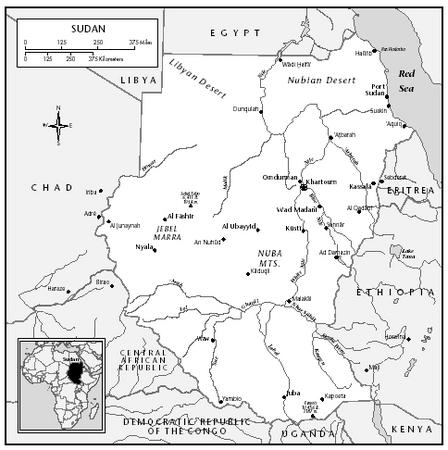

Location and Geography. Sudan is in Africa, south of Egypt. It shares borders with Egypt, Libya, Chad, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, Kenya, and Ethiopia. It is the largest country in Africa and the ninth largest in the world, covering one million square miles (2.59 million square kilometers). The White Nile flows though the country, emptying into Lake Nubia in the north, the largest manmade lake in the world. The northern part of the country is desert, spotted with oases, where most of the population is concentrated. To the east, the Red Sea Hills support some vegetation. The central region is mainly high, sandy plains. The southern region includes grasslands, and along the border with Uganda the Democratic Republic of the Congo, dense forests. The southern part of the country consists of a basin drained by the Nile, as well as a plateau, and mountains, which mark the southern border. These include Mount Kinyeti, the highest peak in Sudan. Rainfall is extremely rare in the north but profuse in the south, which has a wet season lasting six to nine months. The central region of the country generally gets enough rain to support agriculture, but it experienced droughts in the 1980s and 1990s. The country supports a variety of wildlife, including crocodiles and hippopotamuses in the rivers, elephants (mainly in the south), giraffes, lions, leopards, tropical birds, and several species of poisonous reptiles.

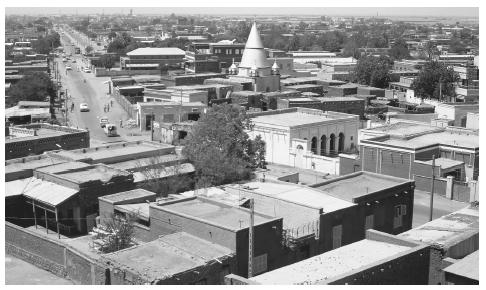

The capital, Khartoum, lies at the meeting point of the White and Blue Niles, and together with Khartoum North and Omdurman forms an urban center known as "the three towns," with a combined population of 2.5 million people. Khartoum is the center for commerce and government; Omdurman is the official capital; and North Khartoum is the industrial center, home to 70 percent of Sudan's industry.

Demography. Sudan has a population of 33.5 million. Fifty-two percent of the population are black and 39 percent are Arab. Six percent are Beja, 2 percent are foreign, and the remaining 1 percent are composed of other ethnicities. There are more than fifty different tribes. These include the Jamala and the Nubians in the north; the Beja in the Red Sea Hills; and several Nilotic peoples in the south, including the Azande, Dinka, Nuer, and Shilluk. Despite a devastating civil war and a number of natural disasters, the population has an average growth rate of 3 percent. There is also a steady rural-urban migration.

Linguistic Affiliation. There are more than one hundred different indigenous languages spoken in Sudan, including Nubian, Ta Bedawie, and dialects of Nilotic and Nilo-Hamitic languages. Arabic is the official language, spoken by more than half of the population. English is being phased out as a foreign language taught in the schools, although it is still spoken by some people.

Symbolism. The flag adopted at independence had three horizontal stripes: blue, symbolizing the Nile

Sudan

River; yellow, for the desert; and green, for the forests and vegetation. This flag was replaced in 1970 with one more explicitly Islamic in its symbolism. It consists of three horizontal stripes: red, representing the blood of Muslim martyrs; white, which stands for peace and optimism; and black, which represents the people of Sudan and recalls the flag flown by the Mahdi during the 1800s. It has a green triangle at the left border, which symbolizes both agriculture and the Islamic faith.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. The first known civilization to inhabit the region of present-day Sudan were the Meroitic people, who lived in the area between the Atbara and Nile Rivers from 590 B.C.E. until 350 B.C.E. , when the city of Meroe was ransacked by the Ethiopians. At about this time, three Christian kingdoms—Nobatia, Makurra, and Alwa—came into power in the area. Several hundred years later, in 641, the Arabs arrived, bringing the Islamic faith with them. They signed a treaty with the Christians to coexist in peace, but throughout the next seven centuries, Christianity gradually died out as more Arabs immigrated to the area and gained converts. In 1504 the Funj people arrived, initiating a rule that would last for nearly three centuries. This was known as the Black Sultanate. Little is known about the origins of the Funj; it is speculated that perhaps they were part of the Shilluk or some other southern tribe that migrated north. Funj rulers converted to Islam, and their dynasty saw the spread of the religion throughout the area.

During the 1800s, the slave trade became a growing business in the region. There had long been a system of domestic slavery, but in the nineteenth century, the Egyptians began taking Sudanese slaves to work as soldiers. Also, European and Arab traders who came to the area looking for ivory established a slave-trade market. This tore apart tribal and family structures and almost entirely eliminated several of the weaker tribes. It was not until the twentieth century that the slave trade was finally abolished.

In 1820, Egypt, at the time part of the Ottoman Empire, invaded the Sudan, and ruled for sixty years until the Sudanese leader Muhammad Ahmed, known as the Mahdi, or "promised one," took over in 1881.

When the British took control of Egypt in 1882, they were wary of the Mahdi's increasing power. In the Battle of Shaykan in 1883, followers of the Sudanese leader defeated the Egyptians and their British supporting troops. In 1885 the Mahdi's troops defeated the Egyptians and the British in the city of Khartoum. The Mahdi died in 1885 and was succeeded by Khalifa Abdullahi.

In 1896 the British and the Egyptians again invaded Sudan, defeating the Sudanese in 1898 at the Battle of Omdurman. Their control of the area would last until 1956. In 1922 the British adopted a policy of indirect rule in which tribal leaders were invested with the responsibility of local administration and tax collection. This allowed the British to ensure their dominion over the region as a whole, by preventing the rise of a national figure and limiting the power of educated urban Sudanese.

Throughout the 1940s an independence movement in the country gained momentum. The Graduates' Congress was formed, a body representing all Sudanese with more than a primary education and whose goal was an independent Sudan.

In 1952 Egypt's King Farouk was dethroned and replaced by the pro-Sudanese General Neguib. In 1953 the British-Egyptian rulers agreed to sign a three-year preparation for independence, and on 1 January 1956 Sudan officially became independent.

Over the next two years the government changed hands several times, and the economy floundered after two poor cotton harvests. Additionally, rancor in the south grew; the region resented its under representation in the new government. (Of eight hundred positions, only six were held by southerners.) Rebels organized a guerrilla army called the Anya Nya, meaning "snake venom."

In November 1958 General Ibrahim Abboud seized control of the government, banning all political parties and trade unions and instituting a military dictatorship. During his reign, opposition grew, and the outlawed political parties joined to form the United Front. This group, along with the Professional Front, composed of doctors, teachers, and lawyers, forced Abboud to resign in 1964. His regime was replaced by a parliamentary system, but this government was poorly organized, and weakened by the ongoing civil war in the south.

In May 1969 the military again took control, this time under Jaafar Nimeiri. Throughout the 1970s, Sudan's economy grew, thanks to agricultural projects, new roads, and an oil pipeline, but foreign debts also mounted. The following decade saw a decline in Sudan's economic situation when the 1984 droughts and wars in Chad and Ethiopia sent thousands of refugees into the country, taxing the nation's already scarce resources. Nimeiri was originally open to negotiating with southern rebels, and in 1972 the Addis Ababa Peace Agreement declared the Southern Region a separate entity. However, in 1985 he revoked that independence, and instituted new laws based on severe interpretations of the Islamic code.

The army deposed Nimeiri in 1985 and ruled for the following four years, until the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC), under the leadership of General Omar Hassan Ahmed al-Bashir, took control. The RCC immediately declared a state of emergency. They did away with the National Assembly, banned political parties, trade unions, and newspapers, and forbade strikes, demonstrations, and all other public gatherings. These measures prompted the United Nations to pass a resolution in 1992 expressing concern over human rights violations. The following year, the military government was disbanded, but General Bashir remained in power as Sudan's president.

Internal conflict between the north and the south continued, and in 1994 the government initiated an offensive by cutting off relief to the south from Kenya and Uganda, causing thousands of Sudanese to flee the country. A peace treaty between the government and two rebel groups in the south was signed in 1996, but fighting continued. In 1998 peace talks, the government agreed to an internationally supervised vote for self-rule in the south, but a date was not specified, and the talks did not result in a cease-fire. As of the late 1990s, the Sudanese People's Liberation Army (SPLA) controlled most of southern Sudan.

In 1996 the country held its first elections in seven years. President Bashir won, but his victory was protested by opposition groups. Hassan al-Turabi, the head of the fundamentalist National Islamic Front (NIF), which has ties with President Bashir, was elected president of the National Assembly. In 1998 a new constitution was introduced, that allowed for a multiparty system and freedom of religion. However, when the National Assembly began to reduce the power of the president, Bashir declared a state of emergency, and rights were again revoked.

National Identity. Sudanese tend to identify with their tribes rather than their nation. The country's borders do not follow the geographical divisions of its various tribes, which in many cases spill over into neighboring countries. Since independence, Muslims in the north have attempted to forge a national Sudanese identity based on Arabic culture and language, at the expense of southern cultures. This has angered many southerners and has proved more divisive than unifying. Within the south, however, the common fight against the north has served to bring together a number of different tribes.

Ethnic Relations. More than one hundred of Sudan's tribes coexist peacefully. However, relations between the north and the south have a history of animosity that dates to independence. The north is largely Arab, and the south has resented their movement to "Arabize" the country, replacing indigenous languages and culture with Arabic. This conflict has led to bloodshed and an ongoing civil war.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

Only 25 percent of the population live in cities or towns; the remaining 75 percent are rural. Khartoum boasts beautiful, tree-lined streets and gardens. It is also home to a large number of immigrants from rural areas, who come looking for work and who have erected shantytowns on the city's fringes.

The biggest town in the south is Juba, near the borders with Uganda, Kenya, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It has wide, dusty streets and is surrounded by expanses of grassland. The town has a hospital, a day school, and a new university.

Other cities include Kassala, the country's largest market town, in the east; Nyala, in the west; Port Sudan, through which most international trade passes; Atbara, in the north; and Wad Medani in the central region, where the independence movement originated.

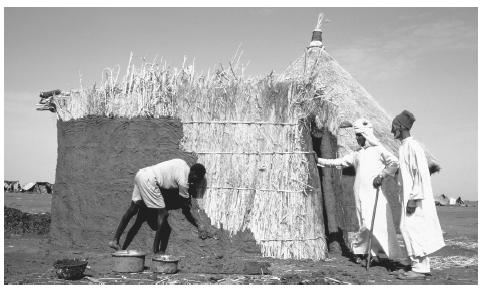

Architecture is varied, and reflects regional climatic and cultural differences. In the northern desert regions, houses are thick-walled mud structures with flat roofs and elaborately decorated doorways (reflecting Arabic influence). In much of the country, houses are made of baked bricks and are surrounded by courtyards. In the south, typical houses are round straw huts with conical roofs, called ghotiya. Nomads, who live throughout Sudan, sleep in tents. The style and material of the tents vary, depending on the tribe; the Rashiaida, for example, use goat hair, whereas the Hadendowa weave their homes from palm fiber.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. The day usually begins with a cup of tea. Breakfast is eaten in the mid- to late morning, generally consisting of beans, salad, liver, and bread. Millet is the staple food, and is prepared as a porridge called asida or a flat bread called kisra. Vegetables are prepared in stews or salads. Ful, a dish of broad beans cooked in oil, is common, as are cassavas and sweet potatoes. Nomads in the north rely on dairy products and meat from camels. In general, meat is expensive and not often consumed. Sheep are killed for feasts or to honor a special guest. The intestines, lungs, and liver of the animal are prepared with chili pepper in a special dish called marara.

Cooking is done in the courtyards outside the house on a tin grill called a kanoon, which uses charcoal as fuel.

Tea and coffee are both popular drinks. Coffee beans are fried, then ground with cloves and spices. The liquid is strained through a grass sieve and served in tiny cups.

A Rasheida resident employs a worker to mud-plaster his house. These mud structures are common in the northern region of the Sudan.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. At the Eid al-Adha, the Feast of the Great Sacrifice, it is customary to kill a sheep, and to give part of the meat to people who cannot afford it themselves. The Eid al-Fitr, or Breaking of the Ramadan Fast, is another joyous occasion, and involves a large family meal. The birthday of the Prophet Muhammad is primarily a children's holiday, celebrated with special desserts: pink sugar dolls and sticky sweets made from nuts and sesame seeds.

Basic Economy. Sudan is one of the twenty-five poorest countries in the world. It has been afflicted by drought and famine and by staggering foreign debt, which nearly caused the country to be expelled from the International Monetary Fund in 1990. Eighty percent of the labor force works in agriculture. Yields have suffered in recent years from decreased rainfall, desertification, and lack of sufficient irrigation systems; currently only 10 percent of arable land is cultivated. Major crops include millet, groundnuts, sesame seed, corn, wheat, and fruits (dates, mangoes, guavas, bananas, and citrus). In areas not conducive to farming, people (many of them nomads) support themselves by raising cattle, sheep, goats, or camels. Ten percent of the labor force is employed in industry and commerce, and 6 percent in the government. There is a shortage of skilled workers, many of whom emigrate to find better work elsewhere. There also is a 30 percent unemployment rate.

Land Tenure and Property. The government owns and operates the country's largest farm, a cotton plantation in the central El Gezira region. Otherwise, much of the land is owned by the different tribes. The various nomadic tribes do not make a claim to any particular territory. Other groups have their own systems for landownership. Among the Otoro in the east-central region, for example, land can be bought, inherited, or claimed by clearing a new area; among the Muslim Fur people in the west, land is administered jointly by kin groups.

Commercial Activities. Souks, or markets, are the centers of commercial activity in the cities and villages. One can buy agricultural products (fruits and vegetables, meat, millet) there, as well as handicrafts produced by local artisans.

Major Industries. Industries include cotton ginning, textiles, cement, edible oils, sugar, soap distilling, and petroleum refining.

The town of Omdurman, situated on the left bank of the White Nile. Together with Khartoum and North Khartoum, the city forms the vast urban region known as "the three towns."

Trade. Cotton is Sudan's primary export, accounting for more than a quarter of foreign currency that enters the country. However, production is vulnerable to climatic fluctuations, and the crop is often hurt by drought. Livestock, sesame, groundnuts, oil, and gum arabic also are exported. These products go to Saudi Arabia, Italy, Germany, Egypt, and France. Sudan imports large quantities of goods, including foodstuffs, petroleum products, textiles, machinery, vehicles, iron, and steel. These products come from China, France, Britain, Germany, and Japan.

Division of Labor. It is traditional for children to follow in the professions of their parents; for the majority of the population, this means continuing in the farming lifestyle; 80 percent of the workforce is in agriculture; 10 percent is in industry and commerce; 6 percent is in government; and 4 percent is unemployed (without a permanent job). In many tribes, political positions, as well as trades and livelihoods, also are hereditary. It is possible nowadays for children to choose professions different from their parents', but most people are constrained by financial considerations. There are facilities for training in a variety of professions, but Sudan still suffers from a shortage of skilled workers.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. Northern Sudanese have more access to education and economic opportunities and generally are better off than southerners. In the south, many of the upper class and politically powerful are Christian and attended missionary schools. In many Sudanese tribes, class and social status are traditionally determined by birth, although in some cases it took a good deal of savvy by the upper classes to maintain their positions. Among the Fur group, ironworkers formed the lowest rung of the social ladder and were not allowed to intermarry with those of other classes.

Symbols of Social Stratification. Among some southern tribes, the number of cattle a family owns is a sign of wealth and status.

Western clothing is common in the cities. Muslim women in the north follow the tradition of covering their heads and entire bodies to the ankles. They wrap themselves in a tobe, a length of semi-transparent fabric which goes over other clothing. Men often wear a long white robe called a jallabiyah, with either a small cap or a turban as a head covering. In rural areas people wear little clothing, or even none at all.

Facial scarring is an ancient Sudanese custom. While it is becoming less common today, it still is practiced. Different tribes have different markings. It is a sign of bravery among men, and beauty in women. The Shilluk have a line of bumps along the forehead. The Nuer have six parallel lines on the forehead, and the Ja'aliin mark lines on their cheeks. In the south, women sometimes have their entire bodies scarred in patterns that reveal their marital status and the number of children they have had. In the north, women often have their lower lips tattooed.

Political Life

Government. Sudan has a transitional government, as it is supposedly moving from a military junta to a presidential system. The new constitution went into effect after being passed by a national referendum in June 1998. The president is both chief of state and head of government. He appoints a cabinet (which is currently dominated by members of the NIF). There is a unicameral legislature, the National Assembly, which consists of 400 members: 275 elected by the populace, 125 chosen by an assembly of interests called the National Congress (also dominated by the NIF). However, on 12 December 1999, uneasy about recent reductions in his powers, President Bashir sent the military to take over the National Assembly.

The country is divided into twenty-six states, or wilayat. Each is administered by an appointed governor.

Leadership and Political Officials. Government officials are somewhat removed from the people; on the local level, governors are appointed rather than elected. A military coup in 1989 reinforced the general feeling of distance between the government and much of the populace. All political parties were banned by the military government. The new constitution legalized them, but this law is under review. The most powerful political organization is the NIF, which has a strong hand in government operations. In the south, the SPLA is the most visible political/military organization, with the goal of self-determination for the region.

Social Problems and Control. There is a twotiered legal system, of civil courts and religious courts. Previously, only Muslims were subject to religious rulings, but Bashir's fundamentalist government holds all citizens to its strict interpretation of Shari'a, or Islamic law. Separate courts handle offenses against the state. Political instability has resulted in high crime rates, and the country is unable to prosecute many of its criminals. The most common crimes are related to the ongoing civil war in the country. Religion and a sense of responsibility to the community are powerful informal social control mechanisms.

Military Activity. The military is composed of 92,000 troops: an army of 90,000, a navy of 1,700, and an air force of 300. The age of service is eighteen. A draft was instituted in 1990 to supply the government with soldiers for the civil war. It is estimated that Sudan spends 7.2 percent of its GNP on military expenses. The Sudanese government estimates that the civil war costs the country one million dollars a day.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

The government supports limited health and welfare programs. Health initiatives concentrate primarily on preventive medicine.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

Various aid organizations have played a role in helping Sudan deal with its significant economic and social problems, including the World Food Program, Save the Children Fund, Oxford Committee for Famine Relief, and Doctors without Borders. The World Health Organization has been instrumental in eliminating smallpox and other diseases.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. Women take care of all domestic tasks and child rearing. In rural areas it is traditional for women to work in the fields as well. While a woman's life in town was traditionally more restricted, it is increasingly common to see females employed outside the home in urban areas. However, it is still the case that only 29 percent of the paid workforce is female.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Sudan is a patriarchal society, in which women are generally accorded a lesser status than men. However, after age forty, women's lives become less constrained. Men and women live largely separate lives, and tend to socialize primarily with members of their own sex. Men often meet in clubs to talk and play cards, while women usually gather in the home.

Several people gather at an irrigation canal in Gezira. The northern part of the country is desert.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Marriages are traditionally arranged by the parents of the couple. This is still the case today, even among wealthier and more educated Sudanese. Matches are often made between cousins, second cousins, or other family members, or if not, at least between members of the same tribe and social class. Parents conduct the negotiations, and it is common for a bride and groom not to have seen each other before the wedding. There is generally a significant age difference between husband and wife. A man must be economically self-sufficient and able to provide for a family before he can marry. He has to be able to furnish an acceptable bride-price of jewelry, clothes, furniture, and among some tribes, cattle. Among the middle class, women usually are married after they finish school, at age nineteen or twenty; in poorer families or in rural areas, the age is younger. Polygyny was a common practice in the past. Divorce, although still considered shameful, is more common today than it once was. Upon dissolution of a marriage, the bride-price is returned to the husband.

Domestic Unit. Extended families often live together under the same roof, or at least nearby. Husband and wife typically move in with the wife's family for at least a year after marriage, or until they have their first child, at which point they move out on their own (although usually to a house in close proximity to the wife's parents).

Inheritance. Islamic law has a provision for inheritance by the oldest male son. Other inheritance traditions vary from tribe to tribe. In the north, among the Arab population, property goes to the eldest son. Among the Azande, a man's property (which consisted primarily of agricultural goods) was generally destroyed upon his death to prevent the accumulation of wealth. Among the Fur, property is usually sold upon the death of its owner; land is owned jointly by kin groups and therefore not divided upon death.

Kin Groups. In different regions of Sudan, traditional clan structures function differently. In some regions, one clan holds all positions of leadership; in others, authority is delegated among various clans and subclans. Kinship ties are reckoned through connections on both the mother's and the father's side, although the paternal line is given stronger consideration.

Socialization

Infant Care. There are several practices to protect newborn babies. For example, Muslims whisper Allah's name in the baby's ear, and Christians make the sign of the cross in water on his or her forehead. An indigenous tradition is to tie an amulet of a fish bone from the Nile around the child's neck or arm. Women carry their babies tied to their sides or backs with cloth. They often bring them along to work in the fields.

Child Rearing and Education. Boys and girls are raised fairly separately. Both are divided into age-specific groups. There are celebrations to mark a group's graduation from one stage to the next. For boys, the transition from childhood to manhood is marked by a circumcision ceremony.

The literacy rate is only 46 percent overall (58% for men and 36% for women), but the overall education level of the population has increased since independence. In the mid-1950s fewer than 150,000 children were enrolled in primary school, compared with more than 2 million today. However, the south still has fewer schools than the north. Most of the schools in the south were established by Christian missionaries during colonial times, but the government closed these schools in 1962. In villages, children usually attend Islamic

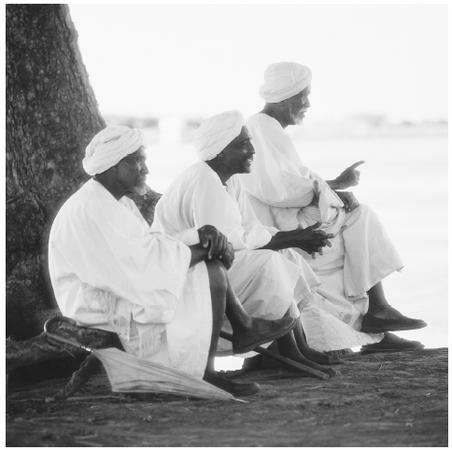

Three men sit by the river in the Ali-Abu region of Sudan. Seventy percent of Sudanese are Sunni Muslim.

schools known as khalwa. They learn to read and write, to memorize parts of the Qur'an, and to become members of an Islamic community—boys usually attend between ages five and nineteen, and girls generally stop attending after age ten. (Girls generally receive less education than boys, as families often consider it more valuable for their daughters to learn domestic skills and to work at home.) As payment at the khalwa, students or their parents contribute labor or gifts to the school. There also is a state-run school system, which includes six years of primary school, three years of secondary school, and either a three-year college preparatory program or four years of vocational training.

Higher Education. Early in the twentieth century, under Anglo-Egyptian rule, the only educational institution beyond the primary level was Grodon Memorial College, established in 1902 in Khartoum. The original buildings of this school are today part of the University of Khartoum, which was founded in 1956. The Kitchener School of Medicine, opened in 1924, the School of Law, and the Schools of Agriculture, Veterinary Science, and Engineering are all part of the university. The capital city alone has three universities. There also is one in Wad Medani and another in the southern city of Juba. The first teacher training school, Bakht er Ruda, opened in 1934, in the small town of Ed Dueim. In addition, a number of technical and vocational schools throughout the country offer training in nursing, agriculture, and other skilled professions. Ahfad University College, which opened in 1920 in Omdurman, as a girls' primary school, has done a great deal to promote women's education and currently enrolls about eighteen hundred students, all female.

Etiquette

Greetings and leave-takings are interactions with religious overtones; the common expressions all have references to Allah, which are taken not just metaphorically but also literally. "Insha Allah" ("if Allah wills") is often heard, as is "alhamdu lillah" ("may Allah be praised").

Food is an important part of many social interactions. Visits typically include tea, coffee, or soda, if not a full meal. It is customary to eat from a common serving bowl, using the right hand rather than utensils. In Muslim households, people sit on pillows around a low table. Before the meal, towels and a pitcher of water are passed around for hand washing.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Seventy percent of the population are Sunni Muslim, 25 percent follow traditional indigenous beliefs, and 5 percent are Christian.

The word "Islam" means "submission to God." It shares certain prophets, traditions, and beliefs with Judaism and Christianity, the main difference being the Muslim belief that Muhammad is the final prophet and the embodiment of God, or Allah. The foundation of Islamic belief is called the Five Pillars. The first, Shahada, is profession of faith. The second is prayer, or Salat. Muslims pray five times a day; it is not necessary to go to the mosque, but the call to prayer echoes out over each city or town from the minarets of the holy buildings. The third pillar, Zakat, is the principle of almsgiving. The fourth is fasting, which is observed during the month of Ramadan each year, when Muslims abstain from food and drink during the daylight hours. The fifth Pillar is the Hajj, the pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca in Saudi Arabia, which every Muslim must make at some time in his or her life.

The indigenous religion is animist, ascribing spirits to natural objects such as trees, rivers, and rocks. Often an individual clan will have its own totem, which embodies the clan's first ancestor. The spirits of ancestors are worshiped and are believed to exercise an influence in everyday life. There are multiple gods who serve different purposes. Specific beliefs and practices vary widely from tribe to tribe and from region to region. Certain cattle-herding tribes in the south place great symbolic and spiritual value on cows, which sometimes are sacrificed in religious rituals.

Christianity is more common in the south than in the north, where Christian missionaries concentrated their efforts prior to independence. Most of the Christians are of the wealthier educated class, as much of the conversion is done through the schools. Many Sudanese, regardless of religion, hold certain superstitions, such as belief in the evil eye. It is common to wear an amulet or a charm as protection against its powers.

Religious Practitioners. There are no priests or clergy in Islam. Fakis and sheiks are holy men who dedicate themselves to the study and teaching of the Qur'an, the Muslim holy book. The Qur'an, rather than any religious leader, is considered to be the ultimate authority and to hold the answer to any question or dilemma one might have. Muezzins give the call to prayer and also are scholars of the Qur'an. In the indigenous religion of the Shilluk, kings are considered holy men and are thought to embody the spirit of the god Nyikang.

Rituals and Holy Places. The most important observation in the Islamic calendar is that of Ramadan. This month of fasting is followed by the joyous feast of Eid al Fitr, during which families visit and exchange gifts. Eid al-Adha commemorates the end of Muhammad's Hajj. Other celebrations include the return of a pilgrim from Mecca, and the circumcision of a child.

Weddings also involve important and elaborate rituals, including hundreds of guests and several days of celebration. The festivities begin with the henna night, at which the groom's hands and feet are dyed. This is followed the next day with the bride's preparation, in which all her body hair is removed, and she, too, is decorated with henna. She also takes a smoke bath to perfume her body. The religious ceremony is relatively simple; in fact, the bride and groom themselves are often not present, but are represented by male relatives who sign the marriage contract for them. Festivities continue for several days. On the third morning, the bride's and groom's hands are tied together with silk thread, signifying their union. Many of the indigenous ceremonies focus on agricultural events: two of the most important occasions are the rainmaking ceremony, to encourage a good growing season, and the harvest festival, after the crops are brought in.

The mosque is the Muslim house of worship. Outside the door there are washing facilities, as cleanliness is a necessary prerequisite to prayer, which demonstrates humility before God. One also must remove one's shoes before entering the mosque. According to Islamic tradition, women are not allowed inside. The interior has no altar; it is simply an open carpeted space. Because Muslims are supposed to pray facing Mecca, there is a small niche carved into the wall pointing out in which direction the city lies.

Among the Dinka and other Nilotic peoples, cattle sheds serve as shrines and gathering places.

Death and the Afterlife. In the Muslim tradition, death is followed by several days of mourning when friends, relatives, and neighbors pay their respects to the family. Female relatives of the deceased wear black for several months to up to a year or more after the death. Widows generally do not remarry, and often dress in mourning for the rest of their lives. Muslims do believe in the afterlife.

Medicine and Health Care

Technically, medical care is provided free of charge by the government, but in actuality few people have access to such care because of the shortage of doctors and other health care personnel. Most trained health workers are concentrated in Khartoum and other parts of the north. Health conditions in most of the country are extremely poor. Malnutrition is common, and increases people's vulnerability to diseases. It is especially pernicious in children. Access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation also are problems, which allow disease to spread rapidly among the population. Malaria, dysentery, hepatitis, and bilharizia are widespread, particularly in poor and rural areas. Bilharzia is transmitted by bathing in water infected with bilharzia larvae. It causes fatigue and liver damage, but once detected can be treated. Schistosomiasis (snail fever) and trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) affect significant numbers of people in the south. Other diseases include measles, whooping cough, syphilis, and gonorrhea.

AIDS is a growing problem in Sudan, particularly in the south, near the borders with Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Khartoum also has a high infection rate, due in part

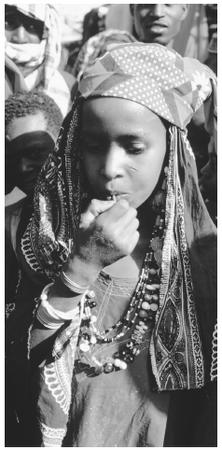

A Fulani woman eats at a market. Food is a large part of many social interactions.

to emigration from the south. The spread of the disease has been exacerbated by uninformed health care workers transmitting it through syringes and infected blood. The government currently has no policy for dealing with the problem.

Secular Celebrations

The principal secular celebrations are on 1 January, Independence Day, and 3 March, National Unity Day

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. There is a National Theater in Khartoum, which hosts plays and other performances. The College of Fine and Applied Arts, also in the capital, has produced a number of well-regarded graphic artists.

Literature. The indigenous Sudanese literary tradition is oral rather than written and includes a variety of stories, myths, and proverbs. The written tradition is based in the Arab north. Sudanese writers of this tradition are known throughout the Arab world.

The country's most popular writer, Tayeb Salih, is author of two novels, The Wedding of Zein and Season of Migration to the North, which have been translated into English. Contemporary Sudanese poetry blends African and Arab influences. The form's best-known practitioner is Muhammad al-Madhi al-Majdhub.

Graphic Arts. Northern Sudan, and Omdurman in particular, are known for silver work, ivory carvings, and leatherwork. In the south, artisans produce carved wooden figures. In the deserts in the eastern and western regions of the country, most of the artwork is also functional, including such weapons as swords and spears.

Among contemporary artists, the most popular media are printmaking, calligraphy, and photography. Ibrahim as-Salahi, one of Sudan's best-known artists, has attained recognition in all three forms.

Performance Arts. Music and dance are central to Sudanese culture and serve many purposes, both recreational and religious. In the north, music reveals strong Arabic influence, and often involves dramatic recitations of verses from the Qur'an. In the south, the indigenous music relies heavily on drums and complex rhythms.

One ritual in which music plays a large part is the zar, a ceremony intended to cure a woman of possession by spirits; it is a uniquely female ritual that can last up to seven days. A group of women play drums and rattles, to which the possessed woman dances, using a prop as an object associated with her particular spirit.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

Because of its extreme poverty and political problems, Sudan cannot afford to allocate resources to programs in the physical and social sciences. The country does have several museums in Khartoum, including the National History Museum; the Ethnographical Museum; and the Sudanese National Museum, which houses a number of ancient artifacts.

Bibliography

Anderson, G. Norman. Sudan in Crisis: The Failure of Democracy, 1999.

Dowell, William. "Rescue in Sudan." Time, 1997.

Haumann, Mathew. Long Road to Peace: Encounters with the People of Southern Sudan, 2000.

Holt, P. M., and Daly, M. W. A History of Sudan: From the Coming of Islam to the Present Day, 2000.

Johnson, Douglas H., ed. Sudan, 1998.

Jok, Jok Madut. Militarization, Gender, and Reproductive Health in Southern Sudan, 1998.

Kebbede, Girma, ed. Sudan's Predicament: Civil War, Displacement, and Ecological Degradation, 1999.

Macleod, Scott. "The Nile's Other Kingdom." Time, 1997.

Nelan, Bruce W., et al. "Sudan: Why Is This Happening Again?" Time, 1998.

Peterson, Scott. Me Against My Brother: At War in Somalia, Sudan, and Rwanda, 2000.

Petterson, Donald. Inside Sudan: Political Islam, Conflict, and Catastrophe, 1999.

Roddis, Ingrid and Miles. Sudan, 2000.

"Southern Sudan's Starvation." The Economist, 1999.

"Sudan." U.N. Chronicle, 1999.

"Sudan's Chance for Peace." The Economist, 2000.

"Sudan Loses Its Chains." The Economist, 1999.

"Terrorist State." The Progressive, 1998.

"Through the Looking Glass." The Economist, 1999.

Woodbury, Richard, et al. "The Children's Crusade." Time, 1998.

Zimmer, Carl. "A Sleeping Storm." Discover, 1998.