Culture of South Africa

Culture Name

South African

Orientation

Identification. South Africa is the only nation-state named after its geographic location; there was a general agreement not to change the name after the establishment of a constitutional nonracial democracy in 1994. The country came into being through the 1910 Act of Union that united two British colonies and two independent republics into the Union of South Africa. After the establishment of the first colonial outpost of the Dutch East India Company at Cape Town in 1652, South Africa became a society officially divided into colonizer and native, white and nonwhite, citizen and subject, employed and indentured, free and slave. The result was a fragmented national identity symbolized and implemented by the white minority government's policy of racial separation. Economic status has paralleled political and social segregation and inequality, with the black African, mixed-race ("Coloured"), and Indian and Pakistani ("Asian") population groups experiencing dispossession and a lack of legal rights. Since the first nonracial elections in 1994, the ruling African National Congress (ANC) has attempted to overcome this legacy and create unified national loyalties on the basis of equal legal status and an equitable allocation of resources.

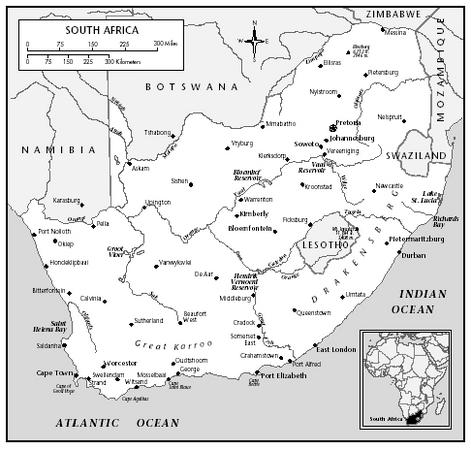

Location and Geography. South Africa has an area of 472,281 square miles (1,223,208 square kilometers). It lies at the southern end of the African continent, bordered on the north by Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and Swaziland; on the east and south by the Indian Ocean; and on the west by the Atlantic Ocean. The independent country of Lesotho lies in the middle of east central South Africa.

Among the prominent features of the topography is a plateau that covers almost two thirds of the center of the country. The plateau complex rises toward the southeast, where it climaxes in the Drakensberg range, part of an escarpment that separates the plateau from the coastal areas. The Drakensburg includes Champagne Castle, the highest peak in the country. The larger portion of the plateau is known as the highveld, which ends in the north in the gold-bearing Witwatersrand, a long, rocky ridge that includes the financial capital and largest city, Johannesburg. The region north of the Witwatersrand, called the bushveld, slopes downward from east to west toward the Limpopo River, which forms the international border. The western section of the plateau, the middleveld, also descends towards the west and varies in elevation between the highveld and bushveld. Between the Drakensburg and the eastern and southern coastline, the land descends to the sea. Toward the eastern coast there is an interior belt of green, hilly country that contains the Cape and Natal midlands. Nearer the coast there is a low-lying plain called the eastern lowveld. Southwest of the plateau the country becomes progressively more arid, giving way to the stony desert of the Great Karroo, bordered on the east by the lower, better watered plateau of the Little Karroo. Separating the dry southern interior from the sandy littoral of the southern coast and West Cape is another range, the Langeberg. On the southwest coast is Table Mountain, with Cape Town, the "Mother City," set in its base, and the coastal plain of the Cape Peninsula tailing off to the south. The southern most point in Africa, Cape Agulhas, lies sixty miles to the east. South Africa also includes part of the Kalahari Desert in the northwest and a section of the Namib Desert in the west. The chief rivers, crossing the country from west to east, are the Limpopo, Vaal, and Orange, which are not navigable but are useful for irrigation. A major new water source was created by the damming of the Orange and the Malibamatso below their sources in the Lesotho Drakensburg. This series

South Africa

of dams, the Lesotho Highlands Water Project, is the largest public works project in Africa.

Demography. The population numbers approximately forty million, comprised of eight officially recognized Bantu-speaking groups; white Afrikaners descended from Dutch, French, and German settlers who speak Afrikaans, a variety of Dutch; English-speaking descendants of British colonists; a mixed-race population that speaks Afrikaans or English; and an immigrant Indian population that speaks primarily Tamil and Urdu. A small remnant of Khoi and San aboriginal populations lives in the extreme northwest. Rural areas are inhabited primarily by Bantu speakers (black African) and Coloured (Khoisan, European, Southeast Asian, and Bantu African) speakers of Afrikaans. The largest language group, the Zulu, numbers about nine million but does not represent a dominant ethnic grouping. Black Africans make up about seventy-seven percent of the population, whites about eleven percent, Coloureds about eight percent, Indians over two percent, and other minorities less than two percent. Most South Africans live in urban areas, with twenty percent of the population residing in the central province of Gauteng, which contains Johannesburg, the surrounding industrial towns, and Pretoria, the administrative capital. Other major urban centers include Durban, a busy port on the central east coast; Cape Town, a ship refitting, wine, and tourist center; and Port Elizabeth, an industrial and manufacturing city on the eastern Cape coast. During the 1990s, urban centers received immigration from other sub-Saharan African countries, and these immigrants are active in small-scale urban commercial ventures.

Linguistic Affiliation. South Africa has eleven official languages, a measure that was included in the 1994 constitution to equalize the status of Bantu languages with Afrikaans, which under the white minority government had been the official language along with English. Afrikaans is still the most widely used language in everyday conversation, while English dominates in commerce, education, law, government, formal communication, and the media. English is becoming a lingua franca of the country, but strong attachments to ethnic, regional, and community linguistic traditions remain, supported by radio and television programming in all the nation's languages. Linguistic subnationalism among ethnic groups such as the Afrikaners remains an important feature of political life.

Symbolism. The nation's racially, ethnically, and politically divided history has produced national and subnational symbols that still function as symbols of the country, and others symbols that are accepted only by certain groups. The monuments to white settler conquest and political dominance, such as the Afrikaner Voortrekker ("pioneer") Monument in Pretoria and the Rhodes Monument honoring the British colonial empire builder and Cape prime minister Cecil Rhodes, remain sectarian symbols. Government buildings that once represented the white minority but now house national democratic institutions, such the union buildings in Pretoria and the parliament buildings in Cape Town, have become national symbols. The nation's wildlife, much of it housed in Kruger National Park, has replaced white "founding fathers" on the currency since 1994. Cape Town's Table Mountain remains the premier geographic symbol. Symbols of precolonial and colonial African nationalism such as the Zulu king Shaka have been promoted to national prominence. Names and symbols of the previous rulers have been retained, such as Kruger National Park and Pretoria, both named for prominent Afrikaner founding fathers, and the springbok, an antelope that is the emblem of the national rugby team.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. South Africa has early human fossils at Sterkfontein and other sites. The first modern inhabitants were the San ("bushman") hunter-gatherers and the Khoi ("Hottentot") peoples, who herded livestock. The San may have been present for thousands of years and left evidence of their presence in thousands of ancient cave paintings ("rock art"). Bantu-speaking clans that were the ancestors of the Nguni (today's amaZulu, amaXhosa, amaSwazi, and vaTsonga peoples) and Tswana-Sotho language groups (today's Batswana and Southern and Northern Basotho) migrated down from east Africa as early as the fifteenth century. These clans encountered European settlers in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, when the colonists were beginning their migrations up from the Cape. The Cape's European merchants, soldiers, and farmers wiped out, drove off, or enslaved the indigenous Khoi herders and imported slave labor from Madagascar, Indonesia, and India. When the British abolished slavery in 1834, the pattern of white legal dominance was entrenched. In the interior, after nearly annihilating the San and Khoi, Bantu-speaking peoples and European colonists opposed one another in a series of ethnic and racial wars that continued until the democratic transformation of 1994. Conflict among Bantu-speaking chiefdoms was as common and severe as that between Bantus and whites. In resisting colonial expansion, black African rulers founded sizable and powerful kingdoms and nations by incorporating neighboring chieftaincies. The result was the emergence of the Zulu, Xhosa, Pedi, Venda, Swazi, Sotho, Tswana, and Tsonga nations, along with the white Afrikaners.

Modern South Africa emerged from these conflicts. The original Cape Colony was established though conquest of the Khoi by the Dutch in the seventeenth century and of the Xhosa by the British in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Natal, the second colony, emerged from the destruction of the Zulu kingdom by Afrikaners and the British between 1838 and 1879. The two former republics of the Orange Free State and Transvaal (South African Republic) were established by Afrikaner settlers who defeated and dispossessed the Basotho and Batswana. Lesotho would have been forcibly incorporated into the Orange Free State without the extension of British protection in 1869. The ultimate unification of the country resulted from the South African War (1899–1902) between the British and the two Afrikaner republics, which reduced the country to ruin at the beginning of the twentieth century. Even after union, the Afrikaners never forgot their defeat and cruel treatment by the British. This resentment led to the consolidation of Afrikaner nationalism and political dominance by mid century. In 1948, the Afrikaner National Party, running on a platform of racial segregation and suppression of the black majority known as apartheid ("separateness"), came to power in a whites-only election. Behind the struggles between the British and the Afrikaners for political dominance there loomed the "Native question": how to keep the aspirations of blacks from undermining the dominance of the white minority. Struggles by the black population to achieve democratic political equality began in the early 1950s and succeeded in the early 1990s.

National Identity. Afrikaners historically considered themselves the only true South Africans and, while granting full citizenship to all residents of European descent, denied that status to people of color until the democratic transition of 1994. British South Africans retain a sense of cultural and social connection to Great Britain without weakening their identity as South Africans. A similar concept of primary local and secondary ancestral identity is prevalent among people of Indian descent. The Bantu-speaking black peoples have long regarded themselves as South African despite the attempts of the white authorities to classify them as less than full citizens or as citizens of ethnic homelands ("Bantustans") between 1959 and 1991. Strong cultural loyalties to African languages and local political structures such as the kingdom and the chieftaincy remain an important component of identity. National identity comes first for all black people, but belonging to an ethnic, linguistic, and regional grouping and even to an ancestral clan has an important secondary status. People once officially and now culturally classified as Coloured regard themselves as South African, as they are a residual social category and their heritage is a blend of all the other cultural backgrounds. Overall, national identity has been forged through a struggle among peoples who have become compatriots. Since 1994, the democratic majority government has avoided imposing a unified national identity from above instead of encouraging social integration through commitment to a common national future.

Ethnic Relations. A strong sense of ethnic separateness or distinctiveness coincides with well-established practical forms of cooperation and common identification. The diversity and fragmentation within ethnic groupings and the balance of tensions between those groups during the twentieth century prevented interethnic civil conflict. While intergroup tensions over resources, entitlements, and political dominance remain, those conflicts are as likely to pit Zulu against Zulu as Zulu against Xhosa or African against Afrikaner.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

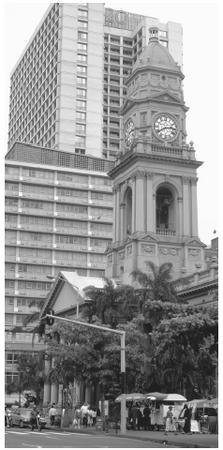

Architecture in the European sense began with the construction of Cape Town by the Dutch late in the seventeenth century. Monumental public buildings, houses of commerce, private dwellings, churches, and rural estates of that period reflect the ornamented but severe style of colonial Dutch architecture, which was influenced by traditions from the Dutch East Indies. Many of the Cape's most stately buildings were constructed with masonry hand carved by Muslim "Malay" artisans brought as slaves from Indonesia. After the British took over the Cape in 1806, buildings in the British colonial style modified the Cape Town architectural style. From colonial India, British merchants and administrators brought the curved metal ornamental roofs and slender lace work pillars that still typify the verandas of cottages in towns and cities throughout the nation. Houses of worship contribute an important architectural aspect even in the smallest towns. In addition to the soaring steeples and classic stonework of Afrikaans Dutch Reformed churches, Anglican churches, synagogues, mosques, and Hindu shrines provide variety to the religious architectural scene.

The domestic architecture of the Khoi and Bantu speaking peoples was simple but strong and serviceable, in harmony with a migratory horticultural and pastoral economy. Precolonial multiple dwelling homesteads, which still exist in rural areas, tended to group lineage clusters or extended families in a semicircular grouping of round or oval one-room dwellings. The term "village" applies most accurately to the closer, multifamily settlements of the Sotho and Tswana peoples, ruled by a local chief, than to the widely scattered family homesteads of the Zulu, Swazi, and Xhosa. Both Sotho-Tswana and Nguni-speaking communities were centered spatially and socially around the dwelling and cattle enclosure of the subchief, which served as a court and assembly for the exercise of authority in local affairs.

Missionaries and the white civil authorities introduced simple European-style square houses along lined streets in "native locations" for Christianized

Post Office Clock Tower in Durban. South Africa's architecture reflects the influence of Dutch and British colonists.

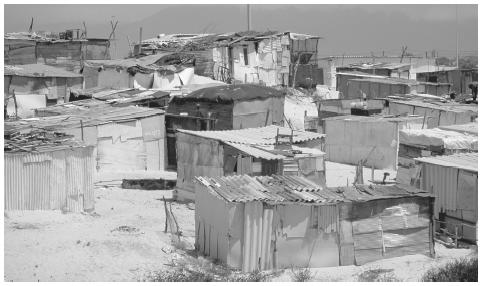

black people, beginning the architectural history of racial segregation. That history culminated in the 1950s in the rearrangement of the landscape to separate Bantu African, Coloured, Indian, and white population groups from one another in "Group Areas." In 1936, the final boundaries of Bantu African reserves limited the rights of residence of those groups to rural homelands scattered over thirteen percent of the country. In the eighty-seven percent of the land proclaimed "White areas," whites lived in town centers and near suburbs, while black workers were housed in more distant "townships" to serve the white economy. The current government does not have the resources to transform this pattern, but economic freedom and opportunity may enable citizens to create a more integrated built environment. In the meantime, the old townships remain with their black population, augmented by miles of new shack settlements containing impoverished rural migrants hoping for a better life in the environmentally overstressed urban areas.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. The consists of the traditionally simple fare of starches and meats characteristic of a farming and frontier society. Early Afrikaner pioneer farmers sometimes subsisted entirely on meat when conditions for trade in cereals were not favorable. A specialized cuisine exists only in the Cape, with its blend of Dutch, English, and Southeast Asian cooking. Food plays a central role in the family and community life of all groups except perhaps the British.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. The gift and provision of food, centering on the ritual slaughtering of livestock, are central to all rites of passage and notable occasions in black communities. Slaughtering and the brewing of traditional cereal beer are essential in securing the participation and goodwill of the ancestors who are considered the guardians of good fortune, prosperity, and well-being. Indian communities maintain their native culinary traditions and apply them on Islamic and Hindu ritual and ceremonial occasions. Afrikaners and Coloured people gather at weekends and special occasions at multifamily barbecues called braais , where community bonds are strengthened.

Basic Economy. South Africa accounts for forty percent of the gross national product of sub-Saharan Africa, but until the late nineteenth century, it had a primarily agricultural economy that had much marginally productive land and was dependent on livestock farming. Because this was the primary economic enterprise of both black Africans and white colonists, conflict between those groups centered on the possession of grazing land and livestock. In 1867, the largest diamond deposits in the world were discovered at Kimberley in the west central area. The wealth from those fields helped finance the exploitation of the greatest gold reef in the world, which was discovered on the Witwatersrand in 1886. Above this gold vein rose the city of Johannesburg. Diamond and gold magnates such as Cecil Rhodes used their riches to finance political ambitions and the extension of the British Empire. On the strength of mining, the country underwent an industrial revolution at the turn of the twentieth century and became a major manufacturing economy by the 1930s. Despite the discovery of new gold deposits in the Orange Free State in the early 1950s, the mining industry is now in decline and South Africa is searching for new means to participate in the global economy.

Land Tenure and Property. African communal notions of territory, land usage, and tenure differ fundamentally from European concepts of land as private or public property. This led to misunderstandings and deliberate misrepresentation in the dealings of white settlers and government officials with African chiefs during the colonial period. In the establishment of African reserves, some aspects of communal and chiefly "tribal trust" land tenure were preserved, and even in white rural areas, forms of communal tenure were still practiced in areas with African communities. African Christian mission communities in some areas drew together to purchase land after colonial conquest and dispossession, only to have that land expropriated again by the Land Acts of 1913 and 1936, which confined black Africans to thirteen percent of the land area.

After the democratic transformation of 1994, programs for land restitution, redistribution, and reform were instituted, but progress has been slow. The white minority still controls eighty percent of the land. In the wake of agricultural land invasions in Zimbabwe, the Department of Land Affairs has pledged to speed land redistribution. However, it is not certain whether dispossessed people who qualify for land redistribution can make profitable economic use of the land.

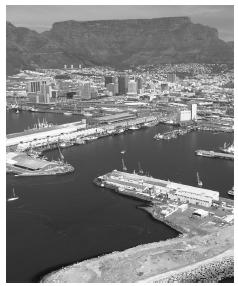

Commercial Activities. Since Cape Town was founded in 1652 as a refreshment, refitting, and trading station of the Dutch East India Company, international commerce has played a central role in the development of the nation. Local black societies did not engage in significant trade, being self-sufficient mixed pastoral economies, and there were no local market centers or long distance trading systems. With the advent of colonial forms of production, black Africans quickly adapted to commercial agricultural production. Their ability to outproduce white settler farms that employed European technology and an African family labor system was a factor in colonial dispossession and enforced wage

Cape Town harbor. The city was formed in 1652 as a trading station of the Dutch East India Company.

labor in rural areas. Until the 1920s, itinerant traders sold manufactured items to African communities and isolated white farms and small farming towns. After 1910, formerly indentured sugar workers from India left these plantations and formed wealthy trading communities. Industries grew after the South African War, and during World War I South Africa supplied weapons to both sides. By the start of the World War II, South Africa had become the only industrialized economy in Africa south of the Sahara. The legal enforcement of white commercial domination until the 1990s has left the majority of private economic and financial resources under the control of the white minority, but this imbalance is being addressed.

Major Industries. Mining is still the largest industry, with profits from diamonds, gold, platinum, coal, and rare metals accounting for the majority of foreign exchange earnings. Currently, a significant portion of those earnings comes from the ownership and management of mines in other countries, particularly in Africa. With the decline in the mining sector, other industries have emerged, including automobile assembly, heavy equipment, wine, fruit and other produce, armaments, tourism, communications and financial services.

Trade. The most important trading partners are the United States and the European Union, particularly Great Britain and Germany, followed by Malaysia, Indonesia, India, and African neighbors such as Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Exports have surged since 1991, and the country has a trade surplus. South Africa is attempting to expand trade with its neighbors by extending its world-class urban infrastructure and industrial, communications, and financial services technologies. Political chaos and economic decline in sub-Saharan Africa, however, have delayed many of these initiatives.

Division of Labor. In precolonial times, division of labor between the sexes and the generations was well defined, and this is still the case in many rural black communities. Before the introduction of the plow, women and girls did most forms of agricultural labor, while men and boys attended to the livestock. Ritual taboos barred women from work involving cattle. Men also dominated law, politics, cattle raiding, and warfare. Some chieftaincies, however, were ruled by women, with women accounting for a significant minority of chiefs today. With the introduction of European agricultural methods in the nineteenth century, men undertook the heavy work of plowing, loading, and transport. That period saw the beginnings of African male labor migration to mines, farms, and commercial and industrial centers. The resultant loss of family labor power was compensated for by the flow of wages to rural communities, but the political and organizational life of rural African communities suffered. As the small towns and urban centers grew, black labor was drawn permanently away from rural communities and toward residence in poorly constructed and overcrowded "locations" attached to the towns. The Indian population also centered in urban areas, especially in Natal, as did Coloured communities other than farm workers in the western and northern Cape. Today there is a crisis in the rural economy, and the pattern of movement of black people off farms and into the urban labor force continues at an accelerated pace.

As educational opportunity has expanded for black citizens, a gradual shift from a racial to a class-based division of labor has begun, and there is now a growing black middle class. Employment is still skewed by racial identity, however, with black unemployment levels that are double those of whites.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. After the founding of Cape Town in 1652, physical indicators of racial origin served as the basis of a color caste system. That system did not prevent interracial sex and procreation, as the shortage of European women was compensated for by the availability of slave women. Slaves, particularly those of mixed parentage, rated higher than free black Africans, and Cape Town soon developed a creole population of free people of color. Over three centuries, the system of racial segregation gradually attained a formal legal status, culminating in the disenfranchisement and dispossession of people of color in the 1960s. In that process, color and class came to be closely identified, with darker peoples legally confined to a lower social and economic status. Despite the color bar in all economic areas, some Africans, Coloureds, and Indians obtained a formal education and a European-style middle class cultural and economic identity as merchants, farmers, colonial civil servants, clerks, teachers, and clergy. It was from this class, educated at mission "Native colleges," that black nationalism and the movement for racial equality recruited many prominent leaders, including Nelson Mandela. Since 1994, people of color have assumed positions in the leading sectors and higher levels of society. Some redistribution of wealth has occurred, with a steady rise in the incomes and assets of black people, while whites have remained at their previous levels. Wealth is still very unevenly distributed by race. Indians and Coloureds have profited the most from the new dispensation, with the middle classes in those groups growing in numbers and wealth.

Symbols of Social Stratification. Before colonialism, the aristocratic chiefs symbolized their authority by wearing special animal-skin clothing, ornaments, and the accoutrements of power, and expressed it through the functioning of chiefly courts and assemblies. Chiefs were entitled by custom to display, mobilize, and increase their wealth through the acquisition of many wives and large herds of cattle. Concentrating their wealth in livestock and people, chiefs of even the highest degree did not live a life materially much better than that of their subjects. Only with the spread of colonial capitalism did luxury goods, high-status manufactured items, and a European education become symbols of social status. European fashions in dress, housing and household utensils, worship, and transport became general status symbols among all groups except rural traditional Africans by the mid-nineteenth century. Since that time, transport has

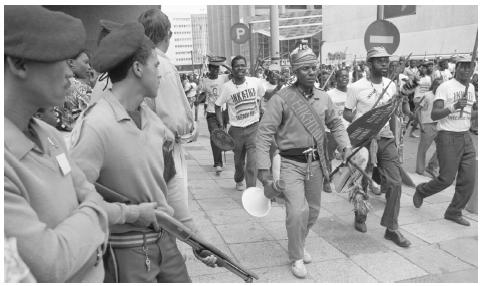

Inkhatha march.

served as a status symbol, with fine horses, pioneer wagons, and horse-drawn carts giving way to imported luxury automobiles.

Political Life

Government. Political life in black African communities centered on the hereditary chieftaincy, in which the senior son of the highest or "great wife" of a chief succeeded his father. In practice, succession was not straightforward, and brothers, older sons of other wives, and widow regents all competed for power. Building large states or polities was difficult under those political conditions, but a number of African chiefs founded national kingdoms, including King Shaka of the Zulu.

European political life began with the Dutch East India Company in the Cape; this was more a mercantile administration than a government. With the transfer of the Cape to Britain in 1806, a true colonial government headed by an imperial governor and a parliamentary prime minister was installed. The legal system evolved as a blend of English common law and European Roman-Dutch law, and people of color, except for the few who attained the status of "free burgers," had few legal rights or opportunities to participate in political life. In the 1830s, the British Crown Colony of Natal was founded on the coast of Zululand in the east. A decade later, Afrikaner emigrants from the Cape ( voortrekkers ), established the independent republics of the Orange Free State and the Transvaal, ruled by an elected president and a popular assembly called a volksraad . The founding and development of European colonies and republics began the long and bitter conflicts between African chiefs, British and Afrikaners, and whites and black Africans that have shaped the nation's history. Since 1994, the country has had universal voting rights and a multi-party nonconstituency "party list" parliamentary system, with executive powers vested in a state president and a ministerial cabinet.

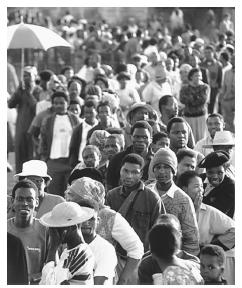

Leadership and Political Officials. The first democratically elected president, Nelson R. Mandela, remains one of the most admired political figures in the world. There are nine provinces, each with a premier selected by the local ruling party and provincial ministerial executives. The party in power since 1994 has been the African National Congress, but other parties currently control two of the provinces.

Social Problems and Control. White minority rule and the policy of racial segregation, disempowerment, and suppression left the government a legacy of problems that amount to a social crisis. Unrepresentative government and repressive racial regulations created mistrust of the law among the black majority. Unemployment is high and rapidly increasing, with the economy losing over a million jobs since 1994. Accompanying this situation are some of the highest crime rates in the world. The education and health care systems are failing in economically depressed communities. The collapse of family farming and the dismissal of thousands of black farm workers have created a rural crisis that has forced dispossessed and unemployed rural people to flock to the cities. Shantytowns ("informal areas") have mushroomed as the government has struggled to provide housing for migrants in a situation of rapid inner-city commercial decline and physical decay. The established black townships also are plagued by unemployment, crime, and insecurity, including drug dealings, alcoholism, rape, domestic violence, and child abuse. The government has imposed high taxes to transfer resources from the wealthy formerly white but now racially mixed suburbs to pay for services and upgrading in the poorer, economically unproductive areas. Although considerable progress has been made, the government and the private sector have been hampered by endemic corruption and white-collar crime. The interracial conflict that could have presented a major difficulty after centuries of colonial and white minority domination has proved to be a manageable aspect of postapartheid political culture, partly as a result of the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission between 1997 and 1999.

Military Activity. The South African Defense Force was notorious for its destabilization of neighboring countries in the 1970s and 1980s and its intervention in the civil war in Angola in the mid-1970s. Since 1994, the army has been renamed the South African National Defense Force (SANDF) and has achieved progress toward racial integration under the command of recently promoted black officers drawn from the armed wing of the ANC, Umkhonto we Sizwe, who serve alongside the white officer corps. The military budget has, however, experienced severe reductions that have limited the ability of the SANDF to respond to military emergencies. The SANDF's major military venture since 1994, the leading of an invasion force to save Lesotho's elected government from a threatened coup, was poorly planned and executed. South Africa has found it difficult to back up its foreign policy objectives with the threat of force. Participation in United Nations peacekeeping missions has been made questionable by high rates of HIV infection in some units.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

The government has not pursued socialistic economic policies, but the socialist principles once espoused by the ANC have influenced social policy. Strong legislation and political rhetoric mandating and advocating programs to aid the formerly dispossessed majority (women, children, and homosexuals), play a prominent role in the government's interventions in society. Land restitution and reform, judicial reform, pro-employee labor regulations, welfare grants, free primary schooling, pre-natal and natal medical care, tough penalties for crimes and child abuse, and high taxes and social spending are all part of the ruling party's efforts to address the social crisis. These problems have been difficult to deal with because only thirty percent of the population contributes to national revenue and because poverty is widespread and deeply rooted. This effort has been made more difficult by restrictions on the level of deficit spending the government can afford without deterring local and foreign investment. A high level of social spending, however, has eased social tension and unrest and helped stabilize the democratic transformation.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

Despite government interference, nongovernmental organizations working to ameliorate the plight of the dispossessed majority, advance democratic ideals, and monitor human rights violations flourished in the 1970s and 1980s. Many of those groups were funded by foreign governmental and private antiapartheid movement donors. With the fall of apartheid and the move toward a nonracial democracy in the 1990s, much of their funding dried up. Also, the new government has been unreceptive to the independent and often socially critical attitude of these organizations. The ANC insists that all foreign funding for social amelioration and development be channeled through governmental departments and agencies. However, bureaucratic obstruction and administrative incapacity have caused some donors to renew their connection with private organizations to implement new and more effective approaches to social problems.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. In rural African communities, women historically were assigned to agricultural tasks (with the exception of herding

A shantytown in Cape Town. Poverty and segregation are persistent legacies of South Africa's former policy of apartheid.

and plowing), and to domestic work and child care. Men tended livestock, did heavy agricultural labor, and ran local political affairs. With the dispossession of the African peasantry, many men have become migrant laborers in distant employment centers, leaving women to manage rural households. In cases where men have not sent their wages to rural families, women have become labor migrants. This pattern of female labor migration has increased as unemployment has risen among unskilled and semiskilled African men. In urban areas, both women and men work outside the home, but women are still responsible for household chores and child care. These domestic responsibilities usually fall to older female children, who have to balance housework and schoolwork.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Male dominance is a feature of the domestic and working life of all the nation's ethnic groups. Men are by custom the head of the household and control social resources. The disabilities of women are compounded when a household is headed by a female single parent and does not include an adult male. The new democratic constitution is based on global humanitarian principles and has fostered gender equality and other human rights. Although not widely practiced, gender equality is enshrined in the legal system and the official discourse of public culture. Slow but visible progress is occurring in the advancement of women in the domestic and pubic spheres, assisted by the active engagement of the many women in the top levels of government and the private sector.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Pre-Christian marriage in black communities was based on polygyny and bridewealth, which involved the transfer of wealth in the form of livestock to the family of the bride in return for her productive and reproductive services in the husband's homestead. Christianity and changing economic and social conditions have dramatically reduced the number of men who have more than one wife, although this practice is still legal. Monogamy is the norm in all the other groups, but divorce rates are above fifty percent and cohabitation without marriage is the most common domestic living arrangement in black and Coloured communities. Despite the fragility of marital bonds, marriage ceremonies are among the most visible and important occasions for sociability and often take the form of an elaborate multisited and lengthy communal feast involving considerable expense.

Domestic Unit. In rural African communities, the domestic unit was historically the homestead,

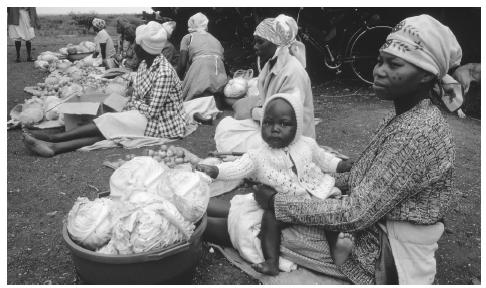

Women and children sit alongside a road with food. Women are responsible for the care of infants, and they typically carry their babies on their backs.

which consisted of a senior man and his wives and their children, each housed in a small dwelling. By the mid-twentieth century, the typical homestead consisted more often of small kindreds composed of an older couple and the younger survivors of broken marriages. The multiroom family house has largely replaced or augmented the multidwelling homestead, just as nuclear and single-parent families have supplanted polygynous homesteads. The nuclear family model is approximated in practice primarily in white families, whereas black, Coloured, and Indian households tend to follow the wider "extended family" model. A new pattern characteristic of the black shantytowns at the margins of established black townships and suburbs consists of households in which unrelated people gather around a core of two or more residents connected by kinship.

Inheritance. Inheritance among white, Coloured, and Indian residents is bilateral, with property passing from parents to children or to siblings of both sexes, with a bias toward male heirs in practice. Among black Africans, the senior son inherited in trust for all the heirs of his father and was responsible for supporting his mother, his junior siblings, and his father's other wives and their children. This system has largely given way to European bilateral inheritance within the extended family, but the older mode of inheritance survives in the responsibility assumed by uncles, aunts, grandparents, and in-laws for the welfare of a deceased child or sibling's immediate family members.

Kin Groups. Recognition of lengthy family lines and extended family relationships are common to all the population groups, most formally among Indians and blacks. For Africans, the clan, a group of people descended from a single remote male ancestor, symbolized by a totemic animal and organized politically around a chiefly title, is the largest kinship unit. These clans often include hundreds of thousands of people and apply their names to branches extending across ethnic boundaries, so that a blood relationship is not an organizing feature of clanship. Among the Nguni-speaking groups, it is against custom for people to marry anyone with their own, their mother's, or grandparents' clan name or clan praise name. Among the Basotho, it is customary for aristocrats to marry within the clan. A smaller unit is the lineage, a kin group of four or five generations descended from a male ancestor traced though the male line. Extended families are the most effective kin units of mutual obligation and assistance and are based on the most recent generations of lineal relationships.

Socialization

Infant Care. Infant care is traditionally the sphere of mothers, grandmothers, and older sisters in black and Coloured communities, and females of all ages carry infants tied with blankets on their backs. Among the social problems affecting the very young in these communities is the high incidence of early teenage pregnancy. Many whites and middle-class families in other ethnic groups have part-time or full-time servants who assist with child care, including the care of infants. The employment of servants to rear children exposes children to adult caregivers of other cultures and allows unskilled women to support their own absent children.

Child Rearing and Education. The family in its varied forms and systems of membership is the primary context for the socialization of the young. The African extended family system provides a range of adult caregivers and role models for children within the kinship network. African families have shown resilience as a socializing agency, but repression and poverty have damaged family structure among the poor despite aid from churches and schools. Middle-class families of all races socialize their children in the manner of suburban Europeans.

Historically, rural African communities organized the formal education of the young around rites of initiation into adulthood. Among the Zulu, King Shaka abolished initiation and substituted military induction for males. These ceremonies, which lasted for several months, taught boys and girls the disciplines and knowledge of manhood and womanhood and culminated in circumcision for children of both sexes. Boys initiated together were led by a son of the chief under whom those age mates formed a military regiment. Girls became marriageable after graduation from the bush initiation school.

Christian missionaries opposed rites of circumcision, but after a long period of decline, traditional initiation has been increasing in popularity as a way of dealing with youth delinquency. Christian and Muslim (Coloured and Indian) clergy introduced formal schools with a religious basis in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Apartheid policies attempted to segregate and limit the training, opportunities, and aspirations of black pupils. Today a unified system of formal Western schooling includes the entire population, but the damage done by the previous educational structure has been difficult to overcome. Schools in black areas have few resources, and educational privilege still exists in the wealthier formerly white suburbs. Expensive private academies and schools maintained by the relatively wealthy Jewish community are among the country's best. Rates of functional illiteracy remain high.

Higher Education. There are more than twenty universities and numerous technical training institutes. These institutions are of varying quality, and many designated as black ethnic universities under apartheid have continued to experience political disturbances and financial crises. Formerly white but now racially mixed universities are also experiencing financial difficulties in the face of a declining pool of qualified entrants and a slow rate of economic growth.

Etiquette

South Africans are by custom polite and circumspect in their speech, although residents of the major urban centers may bemoan the decline of once-common courtesies. Each of the quite different culture groups—corresponding to home language speakers of English, Afrikaans, Tamil and Urdu, and the southern Bantu Languages, cross-cut by religion and country of original origin—has its own specific expressive forms of social propriety and respect.

Black Africans strongly mark social categories of age, gender, kinship, and status in their etiquette. Particular honor and pride of place are granted to age, genealogical seniority, male adulthood, and political position. Rural Africans still practice formal and even elaborate forms of social greeting and respect, even though such forms are paralleled by a high incidence of severe interpersonal and social violence. While the more westernized or cosmopolitan Africans are less formal in the language and gesture of etiquette, the categories of social status are no less clearly marked, whether in the homes of wealthy university graduates or in cramped and crowded working-class bungalows. The guest who does not greet the parents of a household by the name of their senior child preceded by ma or ra (Sesotho: "mother/father of . . . ") or at least an with an emphatic 'me or ntate (Sesotho: mother/father [of the house]) will be thought rude. The youngster who does not scramble from a chair to make way for an adult will draw a sharp reproof.

Comparable forms with cognate emphasis on age, gender, and seniority are practiced in Muslim, Hindu, and Jewish communities according to religious prescriptions and places of original family origin. South Africans of British origin insist on a

Voters wait in line in the first all-race elections, 1994. All South Africans have had the right to vote since this landmark year.

calm, distanced reserve mixed with a pleasant humor in social interactions, regardless of their private opinions of others. Afrikaners are rather more direct and sharp in their encounters, more quick to express their thoughts and feelings towards others, and not given to social legerdemain. In general, despite the aggressive rudeness that afflicts stressful modern urban life everywhere, South Africans are by custom hospitable, helpful, sympathetic, and most anxious to avoid verbal conflict or unsociable manners. Even among strangers, one of the strongest criticisms one can make in South Africa of another is that the person is "rude."

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Despite the socialist roots of the ruling ANC, South Africa is traditionally a deeply religious country with high rates of participation in religious life among all groups. The population is overwhelmingly Christian with only very small Jewish, Muslim, and Hindu minorities. Among Christian denominations, the Calvinist Dutch Reformed Church is by far the largest as most White and some Coloured Afrikaners belong to it. Other important denominations include Roman Catholics, Methodists, Lutherans, Presbyterians, and Anglicans, the last led by Nobel Peace Prize winner Bishop Desmond Tutu. Apostolic and Pentacostal churches also have a large Black membership. Indigenous Black African religion centered on veneration of and guidance from the ancestors, belief in various minor spirits, spiritual modes of healing, and seasonal agricultural rites. The drinking of cereal beer and the ritual slaughter of livestock accompanied the many occasions for family and communal ritual feasting. The most important ceremonies involved rites of the life cycle such as births, initiation, marriage, and funerals.

Religious Practitioners. Indigenous African religious practitioners included herbalists and diviners who attended to the spiritual needs and maladies of both individuals and communities. In some cases their clairvoyant powers were employed by chiefs for advice and prophesy. Historically, Christian missionaries and traditional diviners have been enemies, but this has not prevented the dramatic growth of hybrid Afro-Christian churches, religious movements, prophetism, and spiritual healing alongside mainstream Christianity. Other important religions include Judaism, Islam, and Hinduism. For the Afrikaners, the Dutch Reformed Church has provided a spiritual and organizational foundation for their nationalist cultural politics and ideology.

Rituals and Holy Places. All religions and ethnic subnational groups have founded shrines to their tradition where momentous events have occurred, their leaders are buried, or miracles are believed to have happened. The grave of Sheikh Omar, for example, a seventeenth-century leader of resistance to Dutch rule in the East Indies who was transported to the Cape and became an early leader of the "Malay" community, is sacred to Cape Muslims. Afrikaners regard the site of the Battle of Blood River (Ncome) in 1838 as sacred because their leader Andries Pretorius made a covenant with their God promising perpetual devotion if victory over the vastly more numerous Zulu army were achieved. The long intergroup conflict over the land itself has led to the sacralization of many sites that are well remembered and frequently visited by a great many South Africans of all backgrounds.

Death and the Afterlife. In addition to the beliefs in the soul and afterlife of the varying world religions in South Africa, continued belief in and consultation with family ancestors remains strong among Black Africans. Among the important shrines where the ancestors are said to have caused

People at a Zulu market. Zulu is the largest South African language group, with about nine million speakers, but it does not represent a dominant ethnic grouping.

miracles are the caves of Nkokomohi and Matuoleng in the eastern Free State, both sites of healing sacred to the Basotho, and the holy city of Ekuphakameni in KwaZulu-Natal, built by Zulu Afro-Christian prophet and founder of the Nazarite Jerusalem Church, Isaiah Shembe in 1916. Formal communal graveyards, not a feature of pre-colonial African culture, have since become a focus of ancestral veneration and rootedness in the land. Disused graves and ancestral shrines have most recently figured in the land restitution claims of expropriated African communities lacking formal deeds of title to their former homes.

Medicine and Health Care

There is a first class but limited modern health care sector for those with medical coverage or the money to pay for the treatment. Government-subsidized public hospitals and clinics are overstressed, understaffed, and are struggling to deal with the needs of a majority of the population that was underserved during white minority rule. A highly developed traditional medical sector of herbalists and diviners provides treatment for physical and psycho-spiritual illnesses to millions in the black population, including some people who also receive treatment from modern health professionals and facilities. South Africa has a high HIV infection rate, and if successful strategies for AIDS prevention and care are not implemented, twenty-five percent of the country's young women will die before age thirty.

Secular Celebrations

Secular celebrations and public holidays are much more numerous than religious celebrations. The old holiday calendar consisting of commemorations of milestones in the history of colonial settlement, conquest, and political dominance has not been abandoned. In the service of political reconciliation, old holidays such as 16 December, which commemorates the victory of eight hundred Afrikaner settlers and their black servants over four thousand Zulu at the Battle of Blood River in 1838, is now celebrated as Reconciliation Day. Holidays commemorating significant events in the black struggle for political liberation include Human Rights Day, marking the shooting to death of sixty-one black pass-law protesters by the police in Sharpeville on 21 March 1961, and Youth Day, recalling the beginning of the Soweto uprising, when police opened fire on black schoolchildren protesting the use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction in township schools on 16 June 1976. Other holidays emphasize social advancements guaranteed by the new constitution, such as Women's Day, which also commemorates the march by women of all groups to protest the extension of the pass laws to women in Pretoria on 9 August 1956.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. Pre-colonial African cultures produced a wide range of artistic artifacts for both use and beauty as clothing and personal adornment, beadwork, basketry, pottery, and external house decoration and design. Today these traditions are not only continued but have been developed in new as well as established forms in exquisitely fashioned folk and popular craft work and even painting. Among the most famous of these is the geometric house painting design of the Ndebele people.

Urban South Africa has highly developed traditions in the full range of arts and humanities genres and disciplines, long supported by government and the liberal universities, among the most prominent in Africa. During the colonial period these traditions spread to the non-European population groups who also produced artists, scholars, and public intellectuals of renown despite the obstacles deliberately placed in their path by the White apartheid cultural authorities. Building on the work of artists in exile such as painter Gerald Sekoto, painters and graphic artists vividly expressed the struggles and sufferings of black South Africans during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Social dislocation and poverty along with rich evocations of a regenerated African folk culture have inspired graphic artists of all backgrounds in the transformational 1990s.

Most recently other pressing social concerns have taken priority over the arts and humanities and both public and private support have dwindled. While the government struggles to make the once racially exclusive arts and educational facilities accessible to all, arts councils have experienced severe reductions in funding and many once-vibrant arts institutions are closed or threatened with closure. The government-sponsored Johannesburg Bienniale arts festival has yet to attract a significant audience.

Literature. The country has long had important writers of different cultural and ethnic backgrounds. Black literature thrived under the adverse conditions of apartheid, but today there is no black writer, playwright, or journalist with the stature of E'skia Mphahlele and Alex la Guma from the 1950s through the 1970s. The White population continues to produce world-class literary artists, however, including Nobel Prize winner Nadine Gordimer, twice Booker Prize winner J. M. Coetzee, and distinguished bilingual Afrikaans novelist André Brink.

Graphic Arts. Graphic artists with a rural folk background who have made the transition to the contemporary art world, such as renowned painter Helen Sibidi, have found a ready international market. South Africa too produced a number of world-class art and documentary photographers in the second half of the twentieth century, whose works vividly evoke all aspects of this diverse, powerful conflictual and divided society. Among such photographers are elders Ernest Cole, David Goldblatt, and Peter Magubane, followed by new talents such as Santu Mofokeng.

Performance Arts. Theater, during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s a thriving formal elite and informal popular performing art, has recently fallen on hard times. Even Johannesburg, the urban cultural center of the country, has witnessed the closure of several major downtown theatre complexes that are now surrounded by urban decay, and the virtual disappearance of popular Black township theatre. The grand State Theatre complex in Pretoria has recently been closed due to insolvency and mismanagement.

New opportunities and interesting choreographers are appearing in the field of contemporary Black dance, but audiences and budgets are still painfully small. South Africa's four great symphony orchestras too have either dissolved or are threatened with dissolution. Alternatively popular music, particularly among Black South African musicians and audiences whether in live performances, recordings, or the increasingly varied broadcast industry, is thriving in the new era and holds out great potential for both artistic and financial expansion. South Africa is possessed of video and digital artists with excellent professional training and great talent, but there is only a limited market for their works within the country. Local television production provides them with some employment, but the South African film industry is moribund.

The very slow pace of economic growth and the high and increasing levels of unemployment and taxation have created an unfavorable environment for artistic and intellectual development in the new nonracial society. One sector in which both artistic and financial progress is occurring is in the growth of arts and performance festivals. The greatest of these is the National Arts Festival held every year in Grahamstown, Eastern Cape, drawing large audiences to a feast of the best new work in theatre, film, serious music, lecture programs, and visual arts and crafts. Other local festivals have sprung up after the example of Grahamstown, and all have achieved some measure of success and permanence in the national cultural calendar.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

Since the 1920s, the universities have graduated world-class professionals in the physical and social sciences. Rapid democratization has stressed the higher education system, and public and private funding for the social sciences has declined at a time when the society is facing a social and economic crisis. The physical sciences have fared better, with the opening of new technical institutions and the expansion of professionally oriented science education programs at the universities. The crisis in primary and secondary education has lowered the quality and quantity of entrants to institutions of higher education, and a lack of economic growth has created an inability to absorb highly trained graduates and a skills shortage as those graduates are attracted by better opportunities abroad.

Bibliography

Adam, Heribert, F. van Zyl Slabbert, and K. Moodley. Comrades in Business: Post-Liberation Politics in South Africa, 1997.

Allen, V. L. The History of Black Mineworkers in South Africa, 1992.

Atkinson, Brenda, and Candice Breitz, eds. Grey Areas: Representation, Identity and Politics in Contemporary South African Art , 1999.

Bhana, Surendra, and Bridglal Pachai, eds. A Documentary History of Indian South Africans, 1984.

Bickford-Smith, Vivian, E. van Heyningen, and N. Worden. Cape Town in the Twentieth Century: An Illustrated Social History, 1999.

Bonner, Philip, and Lauren Segal. Soweto: A History, 1998.

Boonzaier, Emile, and John Sharp, eds. South African Keywords, 1988.

Butler, Jeffrey. The Black Homelands of South Africa: The Political and Economic Development of Bophuthatswana and Kwazulu, 1977.

Christopher, A. J. The Atlas of Apartheid, 1994.

Coetzee, J. M. Doubling the Point: Essays and Interviews, 1992.

Coplan, David B. In Township Tonight! South Africa's Black City Music and Theatre, 1985.

Elphick, Richard, and Rodney Davenport, eds. Christianity in South Africa: A Political, Social and Cultural History, 1977.

Fine, Ben, and Zavareh Rustomjee. The Political Economy Of South Africa: From Minerals-Energy Complex to Industrialization, 1996.

Fox, Roddy, and Kate Rowntree, eds. The Geography of South Africa in a Changing World, 2000.

Gerhart, Gail. Black Power in South Africa, 1978.

Gordimer, Nadine. Living in Hope and History: Notes from Our Century, 1999.

Hammond-Tooke, W. D., ed. The Bantu-Speaking Peoples of Southern Africa, 1974.

Harker, John, et al. Beyond Apartheid: Human Resources for a New South Africa, 1991.

Hugo, Pierre, ed. Redistribution and Affirmative Action: Working on the South African Political Economy, 1992.

Human, Linda, ed. Educating and Developing Managers for a Changing South Africa: Selected Essays, 1992.

Kuper, Adam. Wives for Cattle: Bridewealth and Marriage in Southern Africa, 1975.

Mahida, Ebrahim M. History of Muslims in South Africa: A Chronology, 1993.

Mesthrie, Rajend, ed. Language and Social History: Studies in South African Sociolinguistics, 1995.

Muller, Andre L. Minority Interests: The Political Economy of the Coloured and Indian Communities in South Africa, 1968.

Nelson, Harold D. South Africa: A Country Study, 1981.

Pampallis, John. Foundations of the New South Africa, 1991.

——. The Political Directory of South Africa, 1996.

Powell, Ivor. Ndebele: A People and Their Art , 1995.

Reader's Digest Illustrated History of South Africa: The Real Story, 1994.

Sachs, Albie. Advancing Human Rights in South Africa, 1992.

Sampson, Anthony. Mandela: The Authorized Biography, 1999.

South Africa through the Lens: Social Documentary Photography , 1983.

Thompson, Leonard Monteath. A History of South Africa, 1995.

——. The Political Mythology of Apartheid, 1985.

Townsend, R. F. Policy Distortions and Agricultural Performance in the South African Economy, 1997.

Truluck, Anne. No Blood on Our Hands: Political Violence in the Natal Midlands 1987–Mid-1992, 1992.

Unterhalter, Elaine, et al. Apartheid Education and Popular Struggles, 1991.

Van Graan, Mike, and Nicky du Plessis, eds. The South African Handbook on Arts and Culture, 1998.

Van Wyk, Gary. African Painted Houses , 1998.

Western, John. Outcast Cape Town, 1981.

Wilmsen, Edwin N., and Patrick McAllister, eds. The Politics of Difference: Ethnic Premises in a World of Power , 1996.