Culture of Somalia

The culture of Somalia is an amalgamation of traditions in that were developed independently since the proto-Somali era through interaction with neighboring and far away civilizations, including other parts of Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and Indian subcontinent. The hypernym of the term Somali from a geopolitical sense is Horner and from a ethnic sense

Overview

A traditional dabqaad incense burner.

The cultural diffusion of Somali commercial enterprise can be detected in its exotic cuisine, which contains Southeast Asian influences. Due to the Somali people's passionate love for and facility with poetry, Somalia has often been referred to as a "Nation of Poets" and a "Nation of Bards", as, for example, by the Canadian novelist Margaret Laurence. Somalis have a story-telling tradition.

According to Canadian novelist and scholar Margaret Laurence, who originally coined the term "Nation of Poets" to describe the Somali Peninsular, the Eidagale clan were viewed as "the recognized experts in the composition of poetry" by their fellow Somali contemporaries:

Among the tribes, the Eidagalla are the recognized experts in the composition of poetry. One individual poet of the Eidagalla may be no better than a good poet of another tribe, but the Eidagalla appear to have more poets than any other tribe. "if you had a hundred Eidagalla men here," Hersi Jama once told me, "And asked which of them could sing his own gabei ninety-five would be able to sing. The others would still be learning."

Somalis have a rich musical heritage centered on traditional Somali folklore. Most Somali songs are pentatonic; that is, they only use five pitches per octave in contrast to a heptatonic (seven note) scale such as the major scale.

Somali art is the artistic culture of the Somali people, both historic and contemporary. These include artistic traditions in pottery, music, architecture, wood carving and other genres. Somali art is characterized by its aniconism, partly as a result of the vestigial influence of the pre-Islamic mythology of the Somalis coupled with their ubiquitous Muslim beliefs. The country's shape gives a united country the nickname toddobo (seven).

Religion

Main article: Islam in Somalia

With very few exceptions, Somalis are entirely Muslims, the majority belonging to the Sunni branch of Islam and the Shafi‘i school of Islamic jurisprudence.

Merca is an ancient Islamic center in Somalia.

There are two theories about when Somalis began adopting Islam. One states that Islam probably arrived in Somalia in the 7th-century when followers of Muhammad came over to escape persecution from the Quraysh tribe in Mecca. An alternate theory states that Islam was brought to the coastal settlements of Somalia between the 7th- and the 10th-century by seafaring Arab and Persian merchants. The Sunni-Shia split within Islam occurred before Islam spread among Somalis, and Sunnis constitute the overwhelming majority of contemporary Somalis. Somali Sufi religious orders (tariqa) – the Qadiriyya, the Ahmadiya and the Salihiyya – in the form of Muslim brotherhoods have played a major role in Somali Islam and the modern era history of Somalia.

Of the three orders, the less strict Qaadiriya tariqa is the oldest, and it is the sect to which most Somalis belonged. The Qaadiriya order is named after Shaikh Muhiuddin Abdul Qadir Gilani of Baghdad. I. M. Lewis states that Qaadiriya has a high reputation for maintaining a higher standard of Islamic instruction than its rivals.

Ahmadiyah and its sub-sect Salihiyyah preached a puritanical form of Islam, and have rejected the popular sufi practice of tawassul (visiting the tombs of saints to ask mediation). B. G. Martin states that these two orders shared some of the views of the Wahhabis of Arabia. The religious differences between Qaadiriya and Salihiyya were controversial, as Salihis continued to oppose the Qadiris' practice of tawassul, and claimed the act to be invalid and improper religious activity.

The Ahmadiya has the smallest number of adherents of the three orders.

Qur'anic schools (also known as dugsi) remain the basic system of traditional religious instruction in Somalia. It is delivered in Arabic. They provide Islamic education for children. According to the UNICEF, the dugsi system where the content is based on Quran, teaches the greatest number of students and enjoys high parental support, is oftentimes the only system accessible to Somalis in nomadic as compared to urban areas. A study from 1993 found, among other things, that "unlike in primary schools where gender disparity is enormous, around 40 per cent of Qur'anic school pupils are girls; but the teaching staff have minimum or no qualification necessary to ensure intellectual development of children." To address these concerns, the Somali government on its own part subsequently established the Ministry of Endowment and Islamic Affairs, under which Qur'anic education is now regulated

Somali community has produced important Muslim figures over the centuries, many of whom have significantly shaped the course of Islamic learning and practice in the Horn of Africa and the Muslim world.

Religiosity

See also: Islam in Somalia

Mosque in Borama, Republic of Somaliland.

With few exceptions, Somalis are entirely Muslims, the majority belonging to the Sunni branch of Islam and the Shafi`i school of Islamic jurisprudence, although some are also adherents of the Shia Muslim denomination. Sufism, the mystical dimension of Islam, is also well-established, with many local jama'a (zawiya) or congregations of the various tariiqa or Sufi orders. The constitution of Somalia likewise defines Islam as the religion of the Somali Republic, and Islamic Sharia as the basic source for national legislation.

Islam entered the region very early on, as a group of persecuted Muslims had, at Prophet Muhummad's urging, sought refuge across the Red Sea in the Horn of Africa. Islam may thus have been introduced into Somalia well before the faith even took root in its place of origin.

Although Somali women were initially excluded from the many male-dominated religious orders, the all-female institution Abay Siti was formed in the late 19th century, incorporating Somali tradition and Islam.

In addition, the Somali community has produced numerous important Islamic figures over the centuries, many of whom have significantly shaped the course of Muslim learning and practice in the Horn of Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and well beyond. Among these Islamic scholars is the 14th century Somali theologian and jurist Uthman bin Ali Zayla'i of Zeila, who wrote the single most authoritative text on the Hanafi school of Islam, consisting of four volumes known as the Tabayin al-Haqa’iq li Sharh Kanz al-Daqa’iq.

Important Islamic figures

Sheikh Ali Ayanle Samatar, a prominent Somali Islamic scholar.

- Abdirahman bin Isma'il al-Jabarti – 10th century Islamic leader in northern Somalia.

- Sheikh Isaaq Bin Ahmed Al Hashimi – 12th century Islamic leader in the northwestern Somalia area.

- Yusuf bin Ahmad al-Kawneyn – 13th century scholar, philosopher and saint. Associated with the development of Wadaad writing.

- Abadir Umar ar-Rida – 13th century Sheikh and patron saint of Harar.

- Uthman bin Ali Zayla'i – 14th century Somali theologian and jurist who wrote the single most authoritative text on the Hanafi school of Islam, consisting of four volumes known as the Tabayin al-Haqa’iq li Sharh Kanz al-Daqa’iq.

- Sa'id of Mogadishu – 14th century Somali scholar and traveler. His reputation as a scholar earned him audiences with the Emirs of Mecca and Medina. He travelled across the Muslim world and visited Bengal and China.

- Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (c. 1507 – 21 February 1543) – 16th century Imam and military leader that led the Conquest of Abyssinia.

- Nur ibn Mujahid – 16th century Somali Emir and patron saint of Harar.

- Ali al-Jabarti (d. 1492) – 16th century Somali scholar and politician in the Mamluk Empire.

- Hassan al-Jabarti (d. 1774) – Somali mathematician, theologian, astronomer and philosopher; considered one of the great scholars of the 18th century.

- Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti (1753–1825) – Somali scholar living in Cairo that recorded the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt.

- Abd al Aziz al-Amawi (1832–1896) – 19th century influential Somali diplomat, historian, poet, jurist and scholar living in the Sultanate of Zanzibar.

- Shaykh Abd Al-Rahman bin Ahmad al-Zayla'i (1820–1882) – Somali scholar who played a crucial role in the spread of the Qadiriyyah movement in Somalia and East Africa.

- Shaykh Sufi (1829–1904) – 19th century Somali scholar, poet, reformist and astrologer.

- Sheikh Uways Al-Barawi (1847–1909) – Somali scholar credited reviving Islam in 19th century East Africa and with followers in Yemen and Indonesia.

- Mohammed Abdullah Hassan (1856-1920) – Somali religious leader credited with the start of Somali Saalihiya Sufi order, the Dervish movement and being the father of Somali nationalism

- Abdallah al-Qutbi (1879–1952) – Somali polemicist theologian and philosopher; best known for his five-part Al-Majmu'at al-mubaraka ("The Blessed Collection"), published in Cairo.

- Sheikh Muhammad al-Sumali (1910-2005) – Somali scholar and teacher in the Masjid Al-Haram in Mecca. He influenced many of the prominent Islamic scholars of today.

Languages

Main articles: Somali language and Languages of Somalia

The Somali language is the official language of Somalia. It is a member of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family, and its nearest relatives are the Afar and Oromo languages. Somali is the best documented of the Cushitic languages, with academic studies of it dating from before 1900.

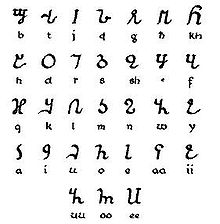

The Osmanya writing script.

Somali dialects are divided into three main groups: Northern, Benaadir and Maay. Northern Somali (or Northern-Central Somali) forms the basis for Standard Somali. Benaadir (also known as Coastal Somali) is spoken on the Benadir coast from Adale to south of Merca, including Mogadishu, as well as in the immediate hinterland. The coastal dialects have additional phonemes which do not exist in Standard Somali. Maay is principally spoken by the Digil and Mirifle (Rahanweyn) clans in the southern areas of Somalia.

Since Somali had long lost its ancient script, a number of writing systems have been used over the years for transcribing the language. Of these, the Somali alphabet is the most widely used, and has been the official writing script in Somalia since the government of former President of Somalia Siad Barre formally introduced it in October 1972.

The script was developed by the Somali linguist Shire Jama Ahmed specifically for the Somali language, and uses all letters of the English Latin alphabet except p, v and z. Besides Ahmed's Latin script, other orthographies that have been used for centuries for writing Somali include the long-established Arabic script and Wadaad's writing. Indigenous writing systems developed in the twentieth century include the Osmanya, Borama and Kaddare scripts, which were invented by Osman Yusuf Kenadid, Sheikh Abdurahman Sheikh Nuur and Hussein Sheikh Ahmed Kaddare, respectively.

In addition to Somali, Arabic is an official national language of Somalia. Many Somalis speak it due to centuries-old ties with the Arab World, the far-reaching influence of the Arabic media, and religious education.

English is also widely used and taught. Italian used to be a major language, but its influence significantly diminished following independence. It is now most frequently heard among older generations who were in contact with the Italians at that time or later as migrants into Italy. Other minority languages include Bravanese, a variant of the Bantu Swahili language that is spoken along the coast by the Bravanese people.

Clan and family structur

Main article: Demographics of Somalia

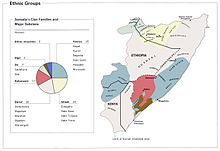

Traditional Somali clans

The clan groupings of the Somali people are important social units, and clan membership plays a central part in Somali culture and politics. Clans are patrilineal and are divided into sub-clans and sub-sub-clans, resulting in extended families.

Major Somali clans include:

- Isaaq

- Darod

- Dir

- Hawiye

- Rahanweyn (Digil and Mirifle)

For more about clan structure visit the Demographics of Somalia

Literature

Main article: Somali literature

Somali language books on display.

Somali scholars have for centuries produced many notable examples of Islamic literature ranging from poetry to Hadith. With the adoption of the Latin alphabet in 1972 to transcribe the Somali language, numerous contemporary Somali authors have also released novels, some of which have gone on to receive worldwide acclaim. Of these modern writers, Nuruddin Farah is probably the most celebrated. Books such as From a Crooked Rib and Links are considered important literary achievements, works which have earned Farah, among other accolades, the 1998 Neustadt International Prize for Literature. Farah Mohamed Jama Awl is another prominent Somali writer who is perhaps best known for his Dervish era novel, Ignorance is the enemy of love. Mohamed Ibrahim Warsame is considered by many to be the greatest living Somali poet, and several of his works have been translated internationally.