Culture of Solomon Islands

Culture Name

Solomon Islander

Alternative Name

Melanesia; Melanesians; Wantoks ("one people," people from the Melanesian region sharing certain characteristics, especially the use of pidgin English).

Orientation

Identification. When Spanish explorer Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira visited the Solomon Islands in 1568, he found some gold at the mouth of what is now the Mataniko River. By a turn of an amused fate, he erroneously thought that this could be one of the locations in which King Solomon (the Israelite monarch) obtained gold for his temple in Jerusalem. Mendaña then named the islands after King Solomon—Solomon Islands.

The islands are most widely known to the outside world for the World War II battles that were fought there, especially on Guadalcanal. Peace prevailed for most of the rest of the century in a country that was sometimes called the "Happy Islands," until ethnic conflict erupted in late 1998.

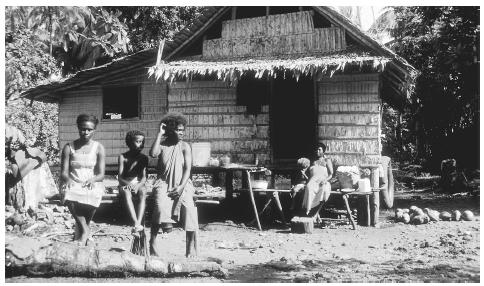

Location and Geography. The Solomon Islands lie northeast of Australia in the South Pacific Ocean. They are part of a long chain of archipelagos called Melanesia, which stretches from Papua New Guinea in the north to New Caledonia and Fiji in the south. Second largest in the Melanesian chain, the Solomon Islands archipelago covers approximately 310,000 square miles (803,000 square kilometers) of ocean and consists of 10,639 square miles (27,556 square kilometers) of land. There are a total of 992 islands in the Solomon Islands, including the six main islands of New Georgia, Choiseul, Santa Isabel, Guadalcanal, Malaita, and San Cristóbal.

The climate of the Solomon Islands is equatorial, tempered by the surrounding ocean. Rainfall is often heavy especially in the interior near the mountains and on the windward sides of the large islands. Coastal areas of the main islands sheltered from the prevailing wind get less rain and, therefore, are drier. Honiara, the capital, is situated on Guadalcanal, in a rain shadow cast by a high mountain range.

Demography. The population of the Solomon Islands is estimated to be approximately 450,000. It is comprised predominantly of Melanesians with the rest of the population consisting of Polynesians, Micronesians, and small pockets of Chinese and Europeans. The annual growth rate is around 3.5 percent.

Most of the population (85 percent) live in villages. Only those with paid employment are found in the urban centers and provincial headquarters of Honiara (the capital), Auki, Gizo, Buala, Kira Kira, and Lata.

Linguistic Affiliation. The Melanesian region of the Pacific is known for its polylinguism. Among Melanesians and Polynesians in the Solomon Islands, approximately 63 to 70 distinct languages are spoken and perhaps an equal number of dialects. Each of the languages and several of the dialects are associated with distinct cultural groups.

Solomon Islanders also speak a variant of English called pidgin English (a form of Creole). And in formal places, such as in church services and in schools, English is spoken although it is usually interspersed with pidgin English and the native languages.

Symbolism. The multiplicity of ethnic groups made it quite difficult for the nation to agree on one symbol for itself. The leaders at independence, therefore, chose an amalgam of symbols to closely represent the different islands and their cultures. This is shown in the national coat of arms, which displays a crocodile and a shark upholding the government (represented by a crown) and a frigate bird

Solomon Islands

supporting both. Also displayed are an eagle, a turtle, a war shield, and some fighting spears. The coat of arms also includes the phrase "to lead is to serve," which characterizes the general belief of the founding fathers who called on every member of the new nation to cherish duty and responsibility.

History and Ethnic Relations

The first discoverers of the Solomon Islands were the island peoples themselves. They settled the main islands and developed land-based communities, first with agriculture and then through animal husbandry, particularly pigs. They also developed fishing and other marine skills, especially in the lagoons.

Subsequent migrants, finding that the big islands were occupied, settled on the outlying islands, most of which are coral outliers. Sikaiana, Reef Islands and the Temotu Islands. These migrants were mostly Polynesians, and they mastered fishing and navigation.

The first contact with Europeans was in 1568 with Spanish explorer Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira. Mendaña left and returned a second time in 1595 with the intent to settle. He died of malaria, and the settlement was short-lived.

Until 1767, when English explorer Philip Carteret landed in the islands, contact with outsiders was limited. It was in the 1800s, when traders and whalers arrived, that contact with Europeans became constant and enduring. Entrepreneurs, church missionaries, and the British colonial government officers soon arrived thereafter.

Before Britain proclaimed protectorate status over the islands in 1893, there was no single centralized politico-cultural system. What existed were numerous autonomous clan-based communities often headed by a male leader with his assistants. Unlike Polynesian societies, there had not been a known overall monarch ruling the islands.

Within the islands, there was intercommunity trading and even warring networks. These networks were further cemented by intermarriages and mutual help alliances.

With the arrival of churches and government, communication was made easier between the islanders, and further networks then developed. The British also put an end to intertribal warfare and conflicts. As a result, the predominant cultures of Melanesia and Polynesia were deeply intertwined with the cultures of the different churches, and both urban and rural lifestyles. Added to this was the introduction of western popular culture.

Emergence of the Nation. The emergence of nationhood came late to most Pacific nations so that the Solomon Islands was given political autonomy from Britain only in 1978, in a peaceful transfer of power. Calls for political independence, however, preceded the 1970s. Starting in the 1990s, Solomon Islanders made several attempts at independence through indigenous movements. Government was an anathema to the leaders of these movements because they did not see why they had to pay taxes when they received little in return from the government.

National Identity. In the Solomon Islands, national culture developed from the convergence of a number of factors. One of the most important is the high level of tolerance and comity developed between different churches in the last century. Unlike the government, church missions have done a lot for the people. They have provided schools, clinics, church buildings, and overall good will. The churches have enabled different cultures to assimilate such teachings as the social gospel of sharing and caring.

Another factor that congeals national culture is the sharing of a lingua franca, the "Solomon Islands pidgin English." Although pidgin English is not a compulsory subject in schools, it is the social glue that cements relationships particularly in a country with multiple languages.

Concomitant with the above is the concept of wantokism. Wantokism is a rallying philosophy that brings together, in common cause, people who are related, those who speak similar languages, those from the same area or island, and even the country as a whole. Its social malleability means that it can be applied in more than one situation especially when one is new to a place or unfamiliar to a group of people. It is a concept in which mutual hospitality is shared among and between different individuals and groups. The concept also traverses national boundaries. It is shared particularly among the three main Melanesian nations, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, and Papua New Guinea.

The development of a national culture was also influenced by the battles Solomon Islanders experienced during World War II. Although the "war was not our war," the fact that many Solomon Islanders had common experiences, including putting their lives at risk to save their country from the enemy (the Japanese), helped unite them into one people.

Ethnic Relations. The ethnic groups of the Solomon Islands reflect the natural division of the islands. A Guadalcanal person would readily identify with others from Guadalcanal. This would equally apply to a Malaita person who would easily relate to another Malaita person. But within the islands, ethnic associations follow the different languages. Having more than seventy languages in the Solomon Islands means, then, that there are more than seventy ethnic groups as well. It was only in the late twentieth century that ethnic relations became politicized, resulting in violence.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

With a relatively small population and large land area, space is affordable in the Solomon Islands. In urban areas, however, the choice of space is limited because of the restricted availability of houses and the nature of freehold land tenure. In such circumstances, Solomon Islanders have to fit into these new environments and quickly adapt to what is generally known as the taon kalsa ("town culture"). This includes developing relationships with one's neighbors from other islands and sharing transportation.

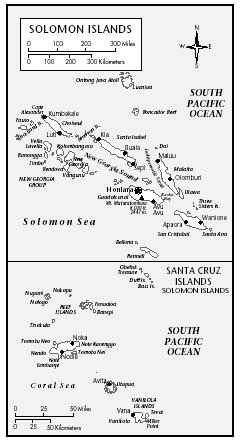

Houses in towns usually take the form of the Western bungalow with three bedrooms on average. These are built mostly of cement and timber, with corrugated iron roofing. A kitchen and other convenient amenities are included therein. Often, however, the practice of having in-house toilets infracts the tradition, as still practiced in rural areas, of having separate toilets for men and women as a sign of deep respect for one's siblings.

In rural areas, large villages are often situated on tribal land. Villages comprise individual families placing their homes next to other relatives. There is usually a village quad (square) where children can play and meetings can be held. Sometimes, village squares are used for games consisting of intervillage competitions. In other areas, family homes are made on artificial islands built over shallow shoals in a lagoon by gathering rocks and piling them together to make a "home over the sea." This lifestyle has several advantages: living over the sea is generally cooler, most of these artificial islands are mosquito-free, and families have greater privacy so they can bring up their children as they wish without the undesirable influences from other children.

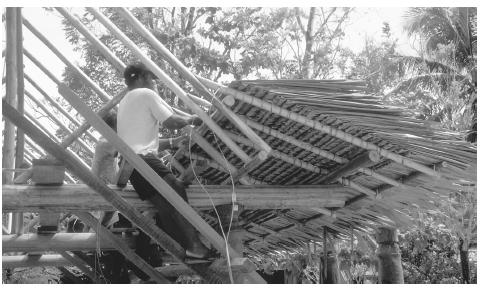

In rural areas, most Solomon Island dwellings are made of sago-palm thatching often with a separate kitchen. Most dwellings are rectangular in shape, raised on stilts with windows for ventilation to take advantage of the frequent land and sea breezes. A separate kitchen is convenient where open-stove cooking is done especially with the family oven, which is used for large Sunday cooking or for public festivals, such as weddings and funerals.

For those who live in mountain areas, which often experience cold nights, houses are generally built low. Often the living area includes a fireplace for heat. In places such as the Kwaio Mountains, on Malaita, where traditional worship is still practiced, men's houses are built separate from family houses. Also, the separately built bisi (menstruating and birthing hut) is where women go during monthly menses and during childbirth.

An important piece of national architecture is the parliament house, which was built as a gift from the United States to Solomon Islands. The building features rich frescoes in the ceiling telling stories of various life-phases in the islands. On the pinnacle of the roof overlooking the whole town are carvings of ancestral gods, which are totemic guides to the different peoples. The building epitomizes the unity of the country besides being a symbolic haven for democratic deliberation and decision making.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Traditionally, yams, panas, and taros are the main staples in the Solomon Islands. These are usually eaten with fish and seashells, for those on the coast, or greens, snails, eels, and opossums, for those inland and in the mountains. The traditional diet does not distinguish between breakfast, lunch, and dinner. What is eaten is usually what is available at that time. Solomon Islanders do not use many spices in their cooking except for coconut milk. During harvesting seasons, breadfruits and ngali nuts are gathered, and eaten or traded.

Today, the traditional diet has changed markedly, especially in urban areas. Rice is becoming the main staple, and is often eaten with tea. For lunch and dinner, rice is eaten with canned meat or fish. The locally-produced Solomon Taiyo (canned tuna) has become a favorite protein source.

For urban families with limited income, breakfast consists of tea with leftovers from previous meals. More affluent families drink tea or coffee and eat buttered bread, rolls, or biscuits. Lunch and dinner are usually the big meals of the day. Eating does not necessary follow time, but as they say, "it follows the tummy." Most families eat together so they can talk. Traditionally, the habit of eating at tables was not the norm. Today, it is becoming one.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. There is a saying that "everyone who goes to a feast expects to eat." Usually a lot of preparation is required for ceremonial occasions. This might involve preparing a pig for the oven, making manioc, taro, yam or swamp-taro pudding, and roasting fish; when it can be afforded, a cow is prepared.

Traditionally, there are no special drinks (particularly alcoholic ones) that go with the food. Water is the main drink. But if the hosts prefer, green coconuts are prepared, to be drunk after the main courses.

Often, in kastom feasts, guests are provided with betel nuts to chew. Similar to desserts, betel nuts are eaten as the final food that tops off a good meal.

Basic Economy. Most of the people are rural villagers who depend on subsistence agriculture for sustenance. Therefore, agriculture and fishing are the mainstays of village life. Any surplus food or fish is bartered or sold at the markets.

Land Tenure and Property. In the Solomon Islands, 85 percent of land is managed under customary tenure, meaning that local clans and members of clan groups have control over it. Traditionally, people do not own the land; the land owns them. People merely have stewardship over the land which is held in "good faith" for them and for subsequent generations.

Commercial Activities. Beginning in the early 1990s, small-scale industries were encouraged, resulting in goods that are sold mostly in the local area at retail and wholesale stores. Examples of these locally-produced products are beer, furniture, and noodles. Otherwise, agricultural products have been the main commodities for sale. In the service sector, hotels and small motels were established in the late twentieth century to encourage small-scale tourism.

Major Industries. Except for Marubeni Fishing Company, which produces canned tuna, and Gold Ridge mine, which produces gold, most of the industries are comprised small or medium-sized businesses. The main industries are geared toward local markets, including the food processing sector, which produces such items as rice, biscuits, beer, and twisties , a brand of confectionery. Other manufacturers produce twisted tobacco, corrugated roofing sheets, nails, fibro canoes and tanks, timber, and buttons.

The tourism industry has only been recently encouraged. The Solomon Islands has stellar scenery, including lagoons, lakes, fauna and flora. The government has encouraged controlled tourism to attract Australians, Japanese, Americans, and scuba divers.

Trade. The export of palm oil and kernels, copra (dried coconut), cocoa, fish, and timber constitute the bulk of the country's trade. The main destinations for these products are Japan, the United Kingdom, Thailand, South Korea, Germany, Australia,

A family relaxes on benches in front of their house in Falamai Village. Stilts and windows provide needed ventilation in the equatorial climate.

the Netherlands, Sweden, and Singapore. Other exported products that are traded in relatively smaller quantities include beer, buttons, precious stones, shell money, and wooden carvings.

Division of Labor. Most Solomon Islanders are self-employed. According to the most recent census data available (1986), 71.4 percent of the economically active population (133, 498) was engaged in non-monetary work in villages, including subsistence farming. The labor force engaged exclusively in wage-earning activities was only 14 percent. A further 14.5 percent was engaged in both wage-earning and subsistence production.

In the formal monetary sector, there were approximately 34,000 employed persons in 1996. Looking at the distribution of this number in terms of economic sectors, 58 percent of the employed were in the service sector including the public service, financial services, and trade; 26 percent in the primary sector, which includes agriculture, fisheries, and forestry; and 16 percent in the secondary sector including manufacturing and construction. It is also useful to look at the relative roles of the public and private sectors in providing employment. In the year under consideration the public sector accounted for 32 percent of the total wage employment while the private sector accounted for the remaining two-thirds.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. The Solomon Islands does not have caste or class divisions as found among some Asian cultures. Instead, the country has different tribal groups found on the different islands. Individuals and groups gravitate towards their own kith and kin. Broader still, they move along island lines or interisland groupings according to various affiliations, including marriages, church memberships, and general friendship.

The emergence of a semblance of class was brought about during the colonial days between those who moved to urban centers and those who remained in villages. Today, those who are employed in the formal sector form a sort of elite class, in contrast to those who are not formally employed either in the public or the private sector. The late twentieth century saw the emergence of another class, a small group of businesspeople.

Symbols of Social Stratification. Social stratification is more obvious in urban areas where people are known by where they live. The well-to-do often live in suburbs such as Ngosi, Tandai, and Lingakiki. Those who live in Kukum Labor line or at the mouth of Mataniko River are usually less affluent. In a similar manner, people are known by the cars they drive, the houses they live in, and the restaurants and bars they frequent.

Political Life

Government. On the eve of political independence in 1978, Solomon Islands' government leaders decided to retain the parliamentary system of government that had been employed during the colonial era. The nation has a governor-general who represents the British monarch, a prime minister as the head of the executive, a speaker of the house who heads parliament, and a chief justice as the highest legal officer. There is no limit to the term a person can serve as prime minister. The speaker is voted for a five-year term, while the chief justice remains in office until retirement unless he or she has proven unable to carry out his or her constitutional duties. The fifty-member parliament is elected every four years.

Leadership and Political Officials. Leadership in traditional culture follows the "big man system." People become leaders when they gain influence by the manipulation of their abilities around followers and resources. Today, most leaders are elected through either consensus or popular ballot.

National leadership in the Solomon Islands has long been dominated by Solomon Mamaloni, who died in January 2000, and Peter Kenilorea. Mamaloni's style of leadership was the "all rounder" who rubs shoulders with almost everybody whom he comes across. He was ready to help those who seek his assistance. It was his professed belief that Solomon Islanders should do things for themselves, as much as possible. Kenilorea, on the other hand, takes a different stance—a gentleman's approach with the usual formality and selectivity. Kenilorea is a real statesman and his contributions to the country have been well-recognized by the jobs he has been given after his occasional spells from politics.

By and large, most Solomon Islanders respect the members of parliament because many leaders have established close rapport with their people. Solomon Islands has experience with coalition governments, resulting from a weak party system, shifting party alliances, and frequent "number contests," often devoid of political merit. Inevitably, this leads to a lot of personal politics and the cult of individuals.

Social Problems and Control. For a long time the Solomon Islands has been free from large-scale social problems. Most problems were concentrated in urban areas, particularly Honiara. Otherwise the rural areas were quite free of conflicts other than the occasional land dispute cases and community arguments that emerged among villagers.

Unlike other countries where sectarian conflicts have flared among members of different religious groups, religious comity in the country is enviable. In the early twenty-first century, the most serious conflict was centered on Guadalcanal, where Guadalcanal residents faced off against resident Malaita people. The conflict arose when the police without due cause or care shot a Guadalcanal man. Thereafter, the conflict raged on. The Guadalcanal people formed an ethnic freedom fighters group called Isatabu Freedom Fighters and chased 20,000 people from Malaita who lived on Guadalcanal. Guadalcanal militants asserted that Malaitans have contributed to many of their problems. Later, a Malaita force was formed, called the Malaita Eagle Force. More than 50 people were killed in the early years of the conflict.

Other social problems prevalent mostly in urban areas include burglary, theft, break-ins, and general social discord between neighbors. During soccer matches, fights often break out between rival supporters. These fracas take serious dimensions when games are held between different island groups, especially during the annual competition between the best provincial teams, competing for the Solomon Cup.

Military Activity. The nation has no standing army or navy. It was only when the Bougainville Crisis spilled over from Papua New Guinea into the Solomon Islands in the early 1990s that the Police Field Force (PFF), a paramilitary unit, was established. Since the Guadalcanal conflict began in late 1998, the PFF has been instrumental in keeping order, arresting offenders and troublemakers and maintaining imposed government decrees in Honiara and around Guadalcanal.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

The government of Bartholomew Ulufalu, which gained power in the 1997 election, was accommodating to major structural adjustment programs (SAPs) pushed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. For a long time, various governments were skeptical about SAPs. The fear was that devaluing the dollar, wage cuts, and other economic stringencies were meant to help only the urban economy. Rural areas, it was believed, would be adversely affected.

Ulufalu, however, as a trained economist, was inclined to adopt the program of the IMF and World Bank, and did so. Although the economy began recovering and revenue collection improved markedly, rural villagers saw their purchasing power diminished. The cost of essential services began to soar. School fees, for example, increased by more than 100 percent. Many rural parents could no longer afford to send their children to school. Thus, the structural adjustment program that was meant to improve social conditions merely exacerbated them.

Nongovernmetal Organizations and Other Associations

Except for the churches, Nongovermental organizations (NGOs) arrived in the Solomon Islands in a big way only in the 1980s. There are the usual ones, which include the Red Cross, Rotary Club, Save the Children, and Catholic Relief. The best known NGO and the one that can be regarded as indigenous is the Solomon Islands Development Trust (SIDT). Well organized, well funded, and innovative in its aims and approach, SIDT has contributed to development in quite a revolutionary way with its emphasis on total change for the person ( metanoia ). It has mobile teams spreading their network in all corners of the country. In addition to a women's group, SIDT also offers opportunities for training and learning for those who would like to look at development and life in more innovative and empowering ways.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. In traditional societies, kastom dictates the roles of women and men. This was true in all the villages. Household duties were the preserve of the women, as were such gardening tasks as organizing garden boundaries, planting, and weeding. Men took care of felling trees to clear areas for gardens, building canoes, hunting, and fishing.

As Solomon Islanders encounter the Western lifestyle, there is a blurring of these traditional roles. Many Solomon Islanders, however, do not challenge traditional roles, rather they attempt to reconcile these roles with their new ones as doctors, lawyers, teachers, or even ministers and pastors in the churches.

Marriage, Family and Kinship

Marriage. Traditionally, parents and adult relatives often arranged marriages. One of the reasons for this was to ensure not individual but social/ communal compatibility. Love was developed not outside of marriage but within marriage. Marriage outside of the clan was often the norm but sometimes arrangements were made for marriage within the clan for exceptional reasons. Great care was taken that close relatives, ranging from first to third cousins, were not involved. The existence of a bride price (better termed "bride gift") differed from one group to the other and from one island group to another. The bride price was not a payment but compensation to the parents and the family for the "loss" of a family member.

Today marriage has changed markedly. Although traditional arranged marriage is still practiced, many marriages are a mixture of individuals making their choice with the blessings of the family. Today marriage can take the form of a court marriage, kastom marriage, church marriage, private marriage, or mere cohabiting. Cohabiting is not widely practiced because it is still socially stigmatized.

Domestic Unit. The family, by definition and through socialization, is "extended" in the Solomon Islands. Even in urban areas, family comes before money and food. As the saying goes, "one cannot cry for money and food but certainly one weeps when one's relative or family member passes away."

Who makes a family decision depends on the criticalness of the issue. Men often make critical decisions because they have to negotiate and account for the decisions if need be. Women often make decisions pertaining to the household, those that involve women's affairs, and those that involve her own relatives. Although men take on the critical decisions, women often play a role in these decisions in the background, out of the gaze of others.

Inheritance. In the Solomon Islands inheritance differs from one group and one island to another, with both patrilineal and matrilineal inheritance being practiced. For example, on Malaita it is patrilineal while on Guadalcanal it is matrilineal. Custom courts in these islands are cognizant of this. Even the national court system considers these differences in its decision making.

Inheritance includes not only material things but also knowledge, wisdom, and magical powers, which are often regarded as heirlooms of the tribe.

Residents of Honiara stroll on the street. As many as seventy distinct languages are spoken in the islands; one legacy of British colonizers is the use of English in formal places.

Fathers often pass on canoes, adzes, spears, and the necessary skills to use onto their sons. Where these are scarce, the first born is often given custody of the items, although the other sons may seek permission for their use from time to time. Mothers often pass on to their daughters body decorations, gardening and fishing skills, and magical incantations.

In towns, inheritance mostly involves money and Western goods and properties, such as houses and cars. In such cases, Western laws apply, especially the British laws of property.

Kin Groups. Belonging to a kinship group is still important in the Solomon Islands. The stigma that comes with not belonging to a kinship group is a heavy one—tantamount to be regarded a bastard.

As mentioned above, there are matrilineal kinship groups on islands such as Guadalcanal, Isabel, Shortlands, and Bougainville, and patrilineal groups on islands such as Malaita. Although one belongs to one's father's group or one's mother's group, secondary membership in the other side is never discounted. Today, there is a mixing of both sides and the strength of such relationship is regarded in terms of "how often and easy people do things together." Being visible during a kinship event is important in order to make oneself known to other members, especially the young ones.

Socialization

Infant Care. It is the parents' primary and foremost responsibility to care for their children. In the Solomon Islands, members of the extended family often help. Solomon Islanders believe that a child, especially an infant, should not have unrelated people close to her or him all the time; a close relative should look after the child. It is believed that infants should be soothed, calmed, or fed every time they cry for attention. It is only when children start to speak and think for themselves that they are slowly left alone.

Child Rearing and Education. Again, it is the parents and relatives who are responsible for the formative education and training of children. Children are taught to watch carefully, ask few questions, and then follow through by participating when asked. A good child is said to behave very much like her mother, if she is a girl, or father, if he is a boy. Good children carry family values with them in life. When one makes a mistake, the parents are often blamed. If the children do well, the parents receive the credit first.

A boy is said to be mature when he can build a house and canoe and make a garden. A girl is regarded as grown up when she can cultivate food gardens, hew wood, carry water, and look after her family and family members even when her mother is absent.

Higher Education. Higher education is highly prized in the Solomon Islands. Although fees are high, parents go to great lengths to pay for at least one of their children to get a decent education. Some wealthy families send their children to such places as New Zealand and Australia for their high school education. Only in 1992 did the first Solomon Islander receive a Ph.D.

Etiquette

In the Solomon Islands, respect for elders and women, particularly in rural areas, is a must. On Malaita, infraction of such rules, especially those pertaining to the dignity of married women, often incurs the immediate payment of compensation. When one is talking to a woman who is not a relative, one is expected to look away as a sign of respect. Strangers are expected to be respected particularly as they are regarded as new and know little of community kastoms. Often when they make mistakes, strangers are gently reminded of community protocols.

Girls are not to show signs of friendliness to strangers, or even boyfriends, when they are with their brothers or relatives. Boys are mutually required to do the same as sign of respect to their sisters and relatives. When guests come to one's house, it is hospitable to allow them to eat first and eat the best. To do otherwise is a sign of moral weakness and lack of respect and dignity for oneself and one's family.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Traditionally, Solomon Islanders believe that ancestors, although invisible, are still around. Therefore, one can invoke their help if need be or ask that their wrath or curse befall one's enemies. Animism was practiced before Christianity reached the islands. For believers in animism, most living things have spirits and it bodes well to maintain a cordial relationship with one's ancestors and the whole ecosystem. For those who live near the coast, totem gods include sharks, octopi, and stingrays. Inland people worship crocodiles, snakes, the eagle, and the owl as deity totems.

Today Christianity pervades most of the country. There is a lot of syncretism between Christian worship and traditional beliefs. People usually pray to the Christian God but use ancestors or those who have recently died as mediators. The belief is that those who have passed on are closer to God and can "see" better.

Today, 90 percent of Solomon Islanders are professed Christians. The five main Christian churches are the Catholic, Anglican, South Sea Evangelical, Seventh Day Adventist, and Christian Fellowship (a derivative of Methodism). Beside Christians, there are traditional practitioners, Mormons, Muslims, and Baha'is.

Religious Practitioners. Teaching and preaching are accented in churches. Healing is one of the sacraments but not the major one. Some people in the Solomon Islands still practice traditional healing. In the Western Solomons, there are healers who can fix broken bones, massage swollen bodies, and cure aching heads. Others have the power to pull cursed objects from a victim's body by sucking them out or by sending another spirit to bring them back. Still others practice black magic.

Rituals and Holy Places. In the Solomon Islands, shrines are always taboo places. These are the places where ancestral remains are kept and ancestral spirits live. Small children are not allowed as the spirits would cause them harm. Nowadays, very few of these places have sacrifices offered as many people have become Christianized.

Today, only Christian rituals are regularly practiced and performed. For example, during the Easter season the stations of the cross is performed and special prayers offered. There are prayer walks in the night as faithful prayer warriors stage spiritual warfare against Satan and his host of angels.

Death and the Afterlife. Death is as important as birth in the Solomon Islands. When people are born, there is celebration. When they die, there is festivity to mark the passing away of a life.

It is believed that when people die, they merely "take the next boat" to the other world. But spirits do not go away immediately after death. They linger for a while as they find it difficult parting from their loved ones. Then after some time, the deceased spirits move on.

When there is a death, the corpse is kept above ground as long as possible. This is to allow all the

Workers tying thatch onto a new house in Honiara, Guadalcanal.

loved ones and family members to pay their last respects. After the deceased is buried, people resume their normal lives. The widow or widower and close relatives then cleanse themselves and continue life again.

Medicine and Health Care

In traditional Solomon Island society, every disease has a spiritual cause or explanation to it. Before Western-introduced diseases, there were traditional cures for most diseases. With the introduction of Western diseases and medicine, the whole equation changed drastically.

Today, the Solomon Islands is accosted in varying degrees with diseases and medical challenges like most third world countries. Lifestyle diseases—including cardiovascular disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes—have been blamed on dietary changes, namely the increasing dependence on imported foods such as white flour, white rice, sugar, and canned meat, as well as an increase in smoking and alcohol consumption. Among vector-borne diseases, malaria is prevalent in the country.

Despite the above, great strides have been made in the country. In the 1990s the average life expectancy was 63 years for men and 65 years for women.

Secular Celebrations

The Solomon Islands has a number of secular celebrations. The first is Independence Day (7 July), which is a colorful day when most island people converge on the capital (Honiara) to celebrate. Queen's birthday (12 June), is usually co-celebrated with Independence Day, and commemorates the birth of Queen Elizabeth II of England. Honors and medals are given to those who have done heroic and great things for the country and people. Christmas Day (25 December) is always a time when families disperse from the capital and meet with their loved ones at their homes to celebrate Christ's birthday. The Christmas holiday is not only a religious holiday, but also the longest holiday of the year for most people. New Year (1 January) is the most celebrated day of each year. There is a tradition of playing a lot of games, especially water games, and competitions between villages.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. Artists in the Solomon Islands are mostly self-supporting. With the encouragement of tourism in the late twentieth century, many more people have taken up the arts, with the specific intention of making money from their artistic skills.

Literature. Literature, both written and oral, has had a sporadic history in the Solomon Islands. It has been seriously studied only since the 1970s. There is a writers' association that has an open membership for all who are interested. This has encouraged both oral and written literatures.

Graphic Arts. The graphic arts are also a relatively new area promoted mostly through touristic advertisements and salesmanship. Graphic arts courses are now offered during summer semesters at the University of the South Pacific Center in Honiara. With more businesses being set up in the capital, many graphic artists have had tremendous income earnings. Sign writing, for example, has been a big moneymaker.

Performance Arts. Music has been a popular pastime in the Solomon Islands. In most of the islands, music is made to keep people together and enhance their companionship. Many Solomon Islanders are natural song composers. The Sulufou Islanders and the Fuaga Brothers are two of the more popular bands.

Drama is valued for its ability to pass on certain messages and influence decisions. Many schools have drama groups that perform historical stories, such as World War II battle tales.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

The Solomon Islands College of Higher Education (SICHE) is an institution founded in 1984 that grew out of the old Teachers' Training College. Since its inception, its achievements have been remarkable. SICHE's schools include industrial arts, agriculture, nursing and health studies, and education. SICHE also has a Solomon Islands studies program, which has not yet been fully developed.

Bibliography

Akin, David. Negotiating culture in East Kwaio, Malaita, Solomon Islands, Ph.D. diss., University of Hawaii, Honolulu, 1993.

Australian Agency for International Development. The Solomon Islands Economy: Achieving Sustainable Economic Development, 1995.

Gegeo, David. "History, Empowerment, and Social Responsibility: Views of a Pacific Islands Indigenous Scholar." Keynote address delivered at the 12th meeting of the Pacific History Association, Honiara, Solomon Islands, June 1998.

——. Kastom and Binis: towards integrating cultural knowledge into rural development in Solomon Islands." Ph.D. diss., University of Hawaii at Manoa, 1994.

——, "Indigenous Knowledge in Community and Literacy Development: Strategies for Empowerment from Within." Unpublished paper, 1997.

Hogbin, Ian H. "Coconuts and Coral Islands," National Geographic Magazine 65 (3), 1934.

Kabutaulaka, Tarcisus. "Solomon Islands: A Review." Contemporary Pacific: A Journal of Island Affairs 11 (2): 443–449, 1999.

LaFranchi, Christopher. Islands Adrift? Comparing Industrial and Small-Scale Economic Options for Maravovo Lagoon Region of the Solomon Islands, 1999.

Lockwood, Victoria S., Thomas G. Harding, and Ben J. Wallace. Contemporary Pacific Societies: Studies in Development and Change, 1993.

O'Callaghan, Mary-Lousie. Solomon Islands: A New Economic Strategy, 1994.

O'Connor, Gulbun Coker. The Moro movement of Guadalcanal, Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1973.

Talu, Alaimu, and Max Quanchi, eds., Messy Entanglements, 1995.

Tryon, Darrell T., and B. D. Hackman. Solomon Island Languages: An Internal Classification, 1983.

United Nations Development Program. Pacific Human Development Report, 1999: Creating Opportunities, 1999.