Culture of Slovenia

Culture Name

Slovenian

Alternative Names

Slovenia is officially known as the Republic of Slovenia and called Slovenija by its residents.

Orientation

Identification. Slovenia takes its name from the Slovenes, the group of South Slavs who originally settled the area. Eighty-seven percent of the population considers itself Slovene, while Hungarians and Italians constitute significant groups and have the status of indigenous minorities under the Slovenian Constitution, guaranteeing them seats in the National Assembly. There are other minority groups, most of whom immigrated, for economic reasons, from other regions of the former Yugoslavia after World War II.

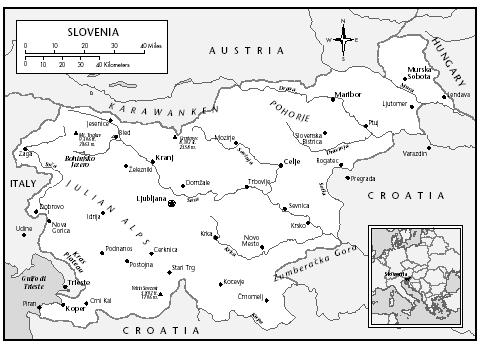

Location and Geography. Slovenia is situated in southeastern Europe on the Balkan Peninsula and is bordered by Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the south and southeast, and Italy and the Adriatic Sea to the west. A mountainous country, Slovenia sits in the foothills of the eastern Alps just south of the Julian Alps, the Kamnik-Savinja Alps, the Karawanken chain, and the Pohorje Massif on the Austrian border. The Adriatic coast of Slovenia is about 39 miles (50 kilometers) in length, running from the border with Italy to the border with Croatia. Slovenia's Kras plateau, between central Slovenia and the Italian frontier, is an interesting area of unusual geological formations, underground rivers, caves, and gorges. Three main rivers located in the northeast, the Mura, the Drava, and the Sava, provide valuable sources of water. On the Pannonian plain to the east and northeast, near the borders with Hungary and Croatia, the landscape is primarily flat. Nevertheless, the majority of the country is hilly to mountainous with about ninety percent of its land at least 650 feet (200 meters) above sea level. Slightly smaller than the state of New Jersey, Slovenia is approximately 7,906 square miles (20,273 square kilometers) in area. In addition to the capital, Ljubljana, other important cities include Maribor, Kranj, Novo Mesto, and Celje. Areas along the coast enjoy a warm Mediterranean climate while those in the mountains to the north have cold winters and rainy summers. The plateaus to the east, where Ljubljana is located, have a mild, more moderate climate with warm to hot summers and cold winters.

Demography. In 2000, Slovenia had an overall population of about 1,970,056 with an overall population density of 252 people per square mile (97 per square kilometer). The majority of the population was ethnically Slovene, a Slavic group. The rest of the population was made up of Croats (2.7 percent), Serbs (2.4 percent), Bosnians (1.3 percent), Hungarians (0.43 percent), Montenegrins (0.22 percent), Macedonians (0.22 percent), Albanians (0.18 percent) and Italians (0.16 percent). Almost half of all Slovenes live in urban areas, mostly in Ljubljana and Maribor, the two largest cities, with the rest of the population distributed throughout rural areas.

Linguistic Affiliation. The official language of the republic, Slovene, is a Slavic language. About 7 percent of the population speaks Serbo-Croatian. Most Slovenes speak at least two languages. Unlike other Slavic cultures, the Slovenes have been greatly influenced by German and Austrian cultures, a result of centuries of rule by the Austrian Habsburgs. Italian influence is evident in the regions that border Italy. These non-Slavic influences are reflected in the Slovene language, which is written in the Latin alphabet, while most Slavic languages use the Cyrillic alphabet. The variety of dialects is also a result of the shared borders with four different nations. During the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation, Slovenia's language, which

Slovenia

had been considered a peasant language compared to the more prestigious German, was used by political and religious factions as an instrument of propaganda. Although initially a political tool, Slovene eventually gained a new level of prestige and provided a linguistic identity that helped shape Slovenia's national identity.

Symbolism. Two important national symbols are the linden tree and the chamois, a European antelope, both of which are abundant throughout the country. Slovenia's flag consists of three horizontal bands of white on the top, blue, and then red on the bottom with a shield in the upper left. On the shield are three white mountain peaks with three gold six-pointed stars above them. The stars were taken from the coat of arms of the Counts of Celje, the Slovenian dynastic house of the late fourteenth–early fifteenth centuries.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. Starting in the sixth century C.E. , the area that is now Slovenia was perpetually invaded by the Avars, a Mongol tribe, who were in turn, driven out by the Slavs. In 623 C.E. , chieftain Franko Samo created the first independent Slovene state, which covered an area from Lake Balaton, now located in Hungary, to the Mediterranean. This independent state persisted until the latter part of the eighth century when it was absorbed into the Frankish empire. In the tenth century, Slovenia fell under the control of the Holy Roman Empire and was reorganized as the duchy of Carantania by the Holy Roman Emperor Otto I (912–973). With the exception of four years of rule by Napoléon (1809–1813), when, along with Croatia, it was a part of the Illyrian Provinces, Slovenia was a part of the Austrian Hapsburg Empire, from 1335 to 1918.

In 1918, at the end of World War I, Slovenia joined with other Slavic groups to form the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. Renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929 by a Serbian monarch, Slovenia and its neighboring Yugoslav states fell under Nazi Germany's control in World War II. Communist partisans, under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito, fiercely resisted the German, Italian, and Hungarian occupation, leading to the establishment of a socialist Yugoslavia toward the end of the war. During the postwar Communist period, Slovenia was the most prosperous region of Yugoslavia.

After Tito's death in 1980, serious disagreements and unrest among Yugoslavia's regions began to grow, and the central government in Belgrade sought to further strengthen its control. The local Slovene government resisted and in September 1989, the General Assembly of the Yugoslav Republic of Slovenia adopted an amendment to its constitution asserting the right of Slovenia to secede from Yugoslavia. On 25 June 1991, the Republic of Slovenia declared its independence. A bloodless tenday war with Yugoslavia followed, ending in the withdrawal of Belgrade's forces and official recognition of Slovenia's status as an independent republic.

As a newly independent state, Slovenia has sought economic stabilization and governmental reorganization, emphasizing its central European heritage and its role as a bridge between eastern and western Europe. With its increased regional profile, including its status as a nonpermanent member of the United Nations Security Council and as a charter member of the World Trade Organization, Slovenia plays an important role in world politics considering its small size.

National Identity. Under the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Slovenia was a part of the Austrian crown lands of Carinthia, Carniola, and Styria, except for a minority of Slovenes living under the republic of Venice. During the Napoleonic Wars, when Slovenia was part of the Illyrian Provinces, a period of relative liberal rule helped fuel the growth of Slovene and Slav nationalism, which ultimately triumphed at the end of World War I. Despite forced transfers during World War II, most Slovenes have managed to remain in Slovenia, and in 1947 Istria, the Slovenian-speaking area of Italy on the Adriatic coast, also joined the republic. More than 87 percent of the population identifies itself as Slovene although minorities are an integral part of the society.

Ethnic Relations. Although Slovenia was a part of Yugoslavia from 1918 to 1991, the country has always identified strongly with central Europe, maintaining a balance between its Slavic culture and language and Western influences. The ethnic conflicts and civil unrest that have plagued other regions of the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s and early twenty-first century, have been avoided in Slovenia. Conscious of its unique position as a bridge between east and west, Slovenia is developing its identity as a newly independent republic while maintaining a balanced relationship with the different cultures of its neighbors.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

Slovenia's towns have many well-preserved buildings representing various styles of architecture dating from the 1100s on. Fine examples of Roman-esque architecture can be found throughout Slovenia, including the church at Sticna Abbey and Podsreda Castle. Architecture from the late Gothic period also survives. Many buildings in older sections of Slovenia's towns are in the Italian Baroque style, particularly in Ljubljana. After a serious earthquake in 1895, extensive sections of Ljubljana were rebuilt in the Art Nouveau style. Throughout Slovenia the focus of town life revolves around the older city centers, squares, churches, and marketplaces.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Slovenia has a rich culinary tradition that is a product of both its climate and its location at the crossroads of central Europe. Slovene culinary heritage is reflective of Mediterranean, Alpine, and Eastern European cultures. Meals are an important part of Slovene family life, and enjoying a snack or a glass of wine at a café with friends is a typical social activity. Although every region in Slovenia has its own specialties, most of Slovenia's oldest traditional dishes are made using flour, buckwheat, or barley, as well as potatoes and cabbage. The town of Idrija, west of Ljubljana, is known for its idrija zlikrofi, spiced potato balls wrapped in thinly rolled dough, and zeljsevka, rolled yeast dough with herb filling. The town of Murska Sobota, Slovenia's northernmost city, is famous for its prekmurska gibanica, a pastry filled with cottage cheese, poppy seeds, walnuts, and apple. Slovenia also produces a variety of wines, an activity dating back to the days when the country was a part of the Roman Empire.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. There are some particular dishes prepared for special occasions including potica, a dessert with a variety of fillings, and braided loaves of traditional bread for Christmas. In country towns the slaughtering of a pig, all parts of which are used to make a variety of pork products, is still a major event.

Basic Economy. After its independence from Yugoslavia in 1991, Slovenia went through a period of transition as it adjusted to economic changes as a new, small republic moving away from socialism. Although the first few years were difficult, Slovenia has now emerged as one of the strongest economies among the former socialist countries of Eastern Europe. The economic outlook, however, remained unclear in the early twenty-first century as the rate of inflation hovered around 10 percent with unemployment at 14.5 percent. Slovenia's loss of its markets in the former Yugoslavia, which once accounted for 30 percent of its exports, has caused the country to modernize its factories and production methods as it seeks to attract foreign investment. Slovenia's growth rate in 2000 was estimated at 3.8 percent with per capita income around $9,000 (U.S.).

Land Tenure and Property. Primogeniture, inheritance by the oldest son, historically determined land distribution in Slovenia. Land and property were kept intact and passed down through families, a tradition that helped limit land fragmentation, which was common in other parts of the Balkans. Despite its years under Yugoslavia's socialist government, Slovenia's strong tradition of family-owned property helped it maintain its distribution of property. Agricultural land, accounting for almost 43 percent of the territory, and forests, covering more than half, make Slovenia the "greenest" country in Europe next to Finland. Nevertheless, 52 percent of Slovenes live in urban areas in small houses and apartment buildings. Formerly state-owned farms and land have been reprivatized.

Commercial Activities. Among the numerous commercial activities in Slovenia, many cater to tourism. Slovenia's proximity to the Alps and the Mediterranean, along with its climate, makes it a popular tourist destination. The business derived from tourist hotels, ski resorts, golf courses, and horseback-riding centers provides employment for a growing number of Slovenes.

Major Industries. Major industries include the production of electrical equipment, processed food, paper and paper products, chemicals, textiles, metal and wood products, and electricity. Other important industries include the manufacturing of shoes, skis, and furniture. Coal mines and steel mills continue to operate and new factories, such as the French Renault car assembly plant, reflect recent foreign investment in Slovenia.

Trade. Germany is Slovenia's most important trading partner both for exports and imports. Other important trading partners include Croatia, Italy, France, and Austria. Exports include chemical products, food and live animals, furniture, machinery, and transportation equipment. Slovenia imports manufactured products and consumer goods.

Division of Labor. In 1994 the process of privatizing state-owned businesses was begun and many Slovenes have taken advantage of these changes to become owners of or shareholders in companies. A large section of the population works in the tourism industry, but only one out of ten people work in agriculture. Many Slovenes, however, pursue small-scale agricultural activities, such as beekeeping and grape growing, as side businesses.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. According to the 1998 census, 87 percent of people are Slovenes. There are approximately 8,500 ethnic Hungarians, 3,000 Italians, and 2,300 Gypsies living in Slovenia. The Hungarian and Italian populations are recognized by the government as indigenous minorities and are protected under the constitution. The Gypsies, however, are viewed with suspicion and are frequently targets of ethnic discrimination. Despite government attempts, past and present, to provide employment and increase school attendance among Gypsies, most of them continue to hold on to their nomadic way of life, shunning mainstream education and jobs. Since the start of civil unrest in other regions of the former Yugoslavia, Slovenia has become a refuge for those escaping from both violence and poor economic conditions. There are also several thousand migrants from Croatia who enter Slovenia every day to work. The peasants, who once accounted for a large part of the population, decreased dramatically in numbers during the post-World War II era as Slovenia, along with the rest of Yugoslavia, underwent a rapid transformation from an agricultural to an industrial society. By the early 1980s, over half of agricultural workers were women. Postwar industrialization created a new class of workers, including government employees who achieved desirable positions through education and political connections. A small intellectual caste has been present in Slovenia since the nineteenth century. A large section of Slovenia's population is now a part of the well-educated, urban-dwelling middle class. Extreme class differences between rich and poor are not present.

Symbols of Social Stratification. Symbols of social stratification include the types of consumer goods found in many Western countries. As Slovenia's

A Slovenian peasant removes corn from the dried cobs while his wife holds his new hat. Clothing is one sign of Slovenia's new affluence; the country has one of the strongest economies among the formerly socialist East European nations.

economy and standard of living have grown, the demand for and ability to purchase consumer goods have increased. Cars, electronic appliances, and clothing are the most immediate signs of social stratification and the new affluence.

Political Life

Government. The process of government reform has been ongoing since the country's emergence as an independent nation in 1991. While some aspects of the former socialist rule have been maintained, the Slovene government has adopted several democratic measures, including a parliamentary form of government. A 1991 constitution guarantees basic civil rights, including universal suffrage for all Slovenes over the age of eighteen, freedom of religion, and freedom of the press. The National Assembly, or Drzavni Zbor, has exclusive control over the passage of new laws and consists of ninety deputies elected for four years by proportional representation. There is also a forty-member Council of State, the Drzavni Svet, which functions as an advisory body and whose members are elected for five-year terms by region and special interest group. The president is the head of state and supreme commander of the armed forces and cannot be elected for more than two five-year terms. Executive power is held by the prime minister and a fifteen-member cabinet.

Leadership and Political Officials. The seven political parties in Slovenia support ideologies ranging from the far right to the center-left. In the 1996 parliamentary elections a centrist alliance of three parties gained the majority. President Milan Kucan was elected for a second term in 1997, and Janez Drnovsek has served as prime minister since the first elections were held in 1992.

Social Problems and Control. Important social problems and issues include the country's transition to a free market economy, an aging population (the average age for men is thirty-five, for women, thirty-eight), creating jobs for an educated population, and coping with the increasing number of migrant workers and refugees.

The crime rate is low but there has been a rise in organized and economic crime since Slovenia's independence and change to privatization. Money laundering is a particularly increasing problem. Slovenia's location between Italy, Austria, and Hungary puts it in the middle of international money-laundering schemes. The Slovene government is actively fighting the resulting problems.

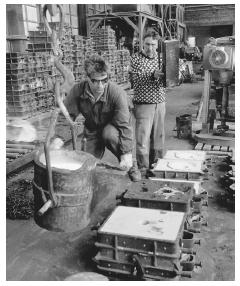

Foundry workers pouring molten metal into molds. While women comprise 45 percent of the workforce, they are largely confined to the welfare, public services, and hospitality fields.

Military Activity. Slovenia requires seven months of military service for all males at age eighteen. As of 1998, the country had an army of 9,550 active duty soldiers as well as a reserve force. A member of the United Nations, Slovenia has signed defense accords with Austria and Hungary.

Gender Roles and Status

Division of Labor by Gender. In Slovenia women comprise 45 percent of the overall workforce and more than 60 percent of the workforce in the agricultural sector. In addition, primary school teachers are almost exclusively women. Industrialization and education have dramatically changed women's roles in the workplace, but aspects of Slovenia's traditionally patriarchal society still persist. Women work primarily in three fields: cultural and social welfare, public services and administration, and the hospitality industry.

The Relative Status Women and Men. Although women were granted complete civil and political rights after World War II, feminist groups state that industrialization has not eradicated the traditional patriarchy but has only created a situation where women are exploited. Women are often treated as sex objects and are still expected to take care of all domestic matters even if they work full-time outside the home.

Marriage, Family and Kinship

Marriage. Despite years of socialism, Slovenian society is still oriented around the extended family. Rights and duties are more rigorously defined by family relationships than in the West. Although the average age for a first marriage has increased, marriage is considered important for maintaining and strengthening family bonds. Religious and cultural influences help keep the divorce rate low.

Domestic Unit. In urban areas, the domestic unit is typically married adults and their children, if they have any, and sometimes older relatives. In rural areas, extended families—often larger than those found in cities—live together or share property. Relatives who are unable to care for themselves usually reside with family members.

Kin Groups. Before the twentieth century, family-based organizations called zadruga held property and farmed land in common. Both formal and customary law determined the obligations and rights of zadruga members.

Socialization

Child Rearing and Education. Education is mandatory and free until age fifteen. After this, students can choose a school that is more specialized if they wish to continue education. Most of the population has some basic education; another 42 percent have secondary schooling (past age fifteen at a high school; and approximately 9 percent receive higher, university education. There is a national, standardized curriculum. Competition for university places is strong. For Slovenes over ten years old, the literacy rate is placed at 99 percent.

Higher Education. Around 36 percent of the people receive postsecondary or higher levels of education. There are thirty institutions of higher learning but only two universities, the University of Ljubljana, founded in 1595, and the University of Maribor. Admittance to the universities is competitive but there are numerous schools that offer professional degrees. It is also possible to obtain a two-year "first stage" degree, equivalent to an associate degree, at the universities.

A bridge leading to a Baroque-style church in Ljubljana. Slovenia's towns have many well-preserved buildings representing various styles of architecture dating from the 1100s on.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. The majority of Slovenes, approximately 71 percent, identify themselves as Roman Catholic; Roman Catholicism has undoubtedly influenced Slovene culture more than any other religious belief. Protestantism gained a strong position during the Reformation in the 1500s but later saw its numbers of practitioners diminish.

Eastern Orthodox Christians comprise 2.5 percent of the population, Protestants, 1 percent, and Muslims, 1 percent. Most of the Protestants belong to the Lutheran church in Murska Sobota. There was once a small Jewish population in Slovenia but Jews were banished from the area in the fifteenth century. Although the ruins of a synagogue can still be seen in Maribor, there is no longer an active Jewish temple anywhere in Slovenia today. The rabbi of Zagreb, Croatia, occasionally holds services for the tiny Jewish community that lives in Ljubljana.

Rituals and Holy Places. There are several churches that are considered pilgrimage sites and places of spiritual renewal. In Brezje, a basilica dedicated to Saint Vid was first established in the 1100s. At the center of this church is a chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary, with paintings by Leopold Layer. The Gothic church of Ptujska Gora, located on top of a mountain, was erected at the end of the fourteenth century and is famous for its beautiful altar. Another pilgrimage church is located at Sveta Gora in the foothills of the Alps. The feast days of the Virgin Mary are the central pilgrimage days for all three churches. There are two monasteries, Sticna Monastery and Pleterje Carthusian Monastery, which are open to visitors who often come not only for spiritual reflection but also to purchase the herbal remedies for which the monks are famous.

Medicine and Health Care

Health care is provided by the government for all of Slovenia's citizens. Life expectancy has increased and is almost at western European levels: seventy years for men and seventy-eight years for women. The birthrate is low, under 10 per 1,000 people, and infant mortality is 5.5 per 1,000 births.

Secular Celebrations

Important secular celebrations include 8 February, Preseren Day, a Slovene cultural day; 1 May, worker's holiday; 25 June, Slovenia Day, and 26 December, Independence Day.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. There is generally a strong interest in supporting the arts in Slovenia and enthusiastic patronage of cultural events. Under the Yugoslav socialist government, arts and culture received state support. As an independent nation, Slovenia is seeking to maintain the same level of support for the arts, although privatization is changing the way institutions and artists are funded.

Literature. Literature has always been enthusiastically supported in Slovenia, and with the country's high literacy rate, this interest continues to grow. The earliest written texts in Slovene, which were religious, date from around 970 C.E. The first published book in Slovene appeared in 1550, and in 1584 a Slovene grammar text and Bible were published. Until the late eighteenth century, however, almost all books published in Slovenia were in Latin or German. Slovenian literature flourished in the early 1800s during the Romantic period and began to develop an identity. During this period France Pres&NA;eren, considered Slovenia's greatest poet, published his works. In the second half of the nineteenth century, Fran Levstik published his interpretation of oral Slovene folktales, and in 1866 Josip Juri published the first long novel completely in Slovene, entitled The Tenth Brother . Slovenian literature immediately before and after World War II was heavily influenced by socialist realism and the struggles of the war period. Various other literary styles, such as symbolism and existentialism, have influenced Slovene writers since the 1960s.

Graphic Arts. Slovenia has an unusual variety of art ranging from Gothic frescoes to contemporary sculpture. The late nineteenth century saw the rise of a Slovene Expressionist school led by the painter Boñidar Jakac. In the early twentieth century a new trend in art emerged as a group of artists joined to form the Club of Independents, some of whom continued working under Tito's socialist government. Slovenia has a small but vibrant art community today that is dominated by the multimedia group Neue Slowenische Kunst and a five-member artists' cooperative called IRWIN. There is also a rich tradition of folk art which is best exemplified by the painted beehives illustrated with folk motifs that are found throughout Slovenia.

Performance Arts. Folk music and dance are an important part of Slovenia's culture. The Institute of Music and National Manuscripts in Ljubljana maintains an archive of the wide variety of traditional songs and fables set to music. Folk dances are still a part of traditional celebrations, and the first ballet school, which was established in Slovenia in 1918 as a part of the Ljubljana Opera, continues to perform. Other dance companies, including contemporary and avant-garde, have also been formed.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

Slovenia has a strong tradition in the sciences, with several important figures, including Janez Vajkard Valvasor, a seventeenth-century mathematician and Fritz Pregl, who won the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 1923. The Slovenian Academy of Arts and Sciences has a research center with fourteen institutes conducting research on all aspects of science, history, and culture.

Bibliography

Arnez, John. Slovenia in European Affairs: Reflections on Slovenian Political History, 1958.

Curtis, Glenn E. Yugoslavia: A Country Study, 1992.

Dickey, Karlene. Slovenia: A Study of the Educational System of the Republic of Slovenia, 1995.

Dizdarevic, Jasmina, and Lucka Letic. Slovenia, 2000.

Fallon, Steve. Slovenia: Lonely Planet Guide, 1995.

Fink-Hafner, Danica, and John Robbins. Making a New Nation: The Formation of Slovenia, 1997.

Minnich, Robert Gary. The Homemade World of Zagaj: An Interpretation of the "Practical Life" among Traditional Peasant Farmers in West Haloze, Slovenia, 1979.

Svetlik, Ivan. Social Policy in Slovenia: Between Tradition and Innovation, 1992.

Tollefson, James W. The Language Situation and Language Policy in Slovenia, 1981.