Culture of Malaysia

Culture Name

Malaysian

Alternative Names

Outsiders often mistakenly refer to things Malaysian as simply "Malay," reflecting only one of the ethnic groups in the society. Malaysians refer to their national culture as kebudayaan Malaysia in the national language.

Orientation

Identification. Within Malaysian society there is a Malay culture, a Chinese culture, an Indian culture, a Eurasian culture, along with the cultures of the indigenous groups of the peninsula and north Borneo. A unified Malaysian culture is something only emerging in the country. The important social distinction in the emergent national culture is between Malay and non-Malay, represented by two groups: the Malay elite that dominates the country's politics, and the largely Chinese middle class whose prosperous lifestyle leads Malaysia's shift to a consumer society. The two groups mostly live in the urban areas of the Malay Peninsula's west coast, and their sometimes competing, sometimes parallel influences shape the shared life of Malaysia's citizens. Sarawak and Sabah, the two Malaysian states located in north Borneo, tend to be less a influential part of the national culture, and their vibrant local cultures are shrouded by the bigger, wealthier peninsular society.

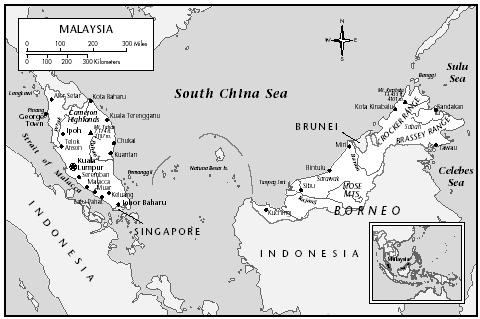

Location and Geography. Malaysia is physically split between west and east, parts united into one country in 1963. Western Malaysia is on the southern tip of the Malay peninsula, and stretches from the Thai border to the island of Singapore. Eastern Malaysia includes the territories of Sabah and Sarawak on the north end of Borneo, separated by the country of Brunei. Peninsular Malaysia is divided into west and east by a central mountain range called the Banjaran Titiwangsa. Most large cities, heavy industry, and immigrant groups are concentrated on the west coast; the east coast is less populated, more agrarian, and demographically more Malay. The federal capital is in the old tinmining center of Kuala Lumpur, located in the middle of the western immigrant belt, but its move to the new Kuala Lumpur suburb of Putra Jaya will soon be complete.

Demography. Malaysia's population comprises twenty-three million people, and throughout its history the territory has been sparsely populated relative to its land area. The government aims for increasing the national population to seventy million by the year 2100. Eighty percent of the population lives on the peninsula. The most important Malaysian demographic statistics are of ethnicity: 60 percent are classified as Malay, 25 percent as of Chinese descent, 10 percent of Indian descent, and 5 percent as others. These population figures have an important place in peninsular history, because Malaysia as a country was created with demography in mind. Malay leaders in the 1930s and 1940s organized their community around the issue of curbing immigration. After independence, Malaysia was created when the Borneo territories with their substantial indigenous populations were added to Malaya as a means of exceeding the great number of Chinese and Indians in the country.

Linguistic Affiliation. Malay became Malaysia's sole national language in 1967 and has been institutionalized with a modest degree of success. The Austronesian language has an illustrious history as a lingua franca throughout the region, though English is also widely spoken because it was the administrative language of the British colonizers. Along with Malay and English other languages are popular: many Chinese Malaysians speak some combination of Cantonese, Hokkien, and/or Mandarin; most Indian Malaysians speak Tamil; and

Malaysia

numerous languages flourish among aboriginal groups in the peninsula, especially in Sarawak and Sabah. The Malaysian government acknowledges this multilingualism through such things as television news broadcasts in Malay, English, Mandarin, and Tamil. Given their country's linguistic heterogeneity, Malaysians are adept at learning languages, and knowing multiple languages is commonplace. Rapid industrialization has sustained the importance of English and solidified it as the language of business.

Symbolism. The selection of official cultural symbols is a source of tension. In such a diverse society, any national emblem risks privileging one group over another. For example, the king is the symbol of the state, as well as a sign of Malay political hegemony. Since ethnic diversity rules out the use of kin or blood metaphors to stand for Malaysia, the society often emphasizes natural symbols, including the sea turtle, the hibiscus flower, and the orangutan. The country's economic products and infrastructure also provide national logos for Malaysia; the national car (Proton), Malaysia Airlines, and the Petronas Towers (the world's tallest buildings) have all come to symbolize modern Malaysia. The government slogan "Malaysia Boleh!" (Malaysia Can!) is meant to encourage even greater accomplishments. A more humble, informal symbol for society is a salad called rojak, a favorite Malaysian snack, whose eclectic mix of ingredients evokes the population's diversity.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. The name Malaysia comes from an old term for the entire Malay archipelago. A geographically truncated Malaysia emerged out of the territories colonized by Britain in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Britain's representatives gained varying degrees of control through agreements with the Malay rulers of the peninsular states, often made by deceit or force. Britain was attracted to the Malay peninsula by its vast reserves of tin, and later found that the rich soil was also highly productive for growing rubber trees. Immigrants from south China and south India came to British Malaya as labor, while the Malay population worked in small holdings and rice cultivation. What was to become East Malaysia had different colonial administrations: Sarawak was governed by a British family, the Brookes (styled as the "White Rajas"), and Sabah was run by the British North Borneo Company. Together the cosmopolitan hub of British interests was Singapore, the central port and center of publishing, commerce, education, and administration. The climactic event in forming Malaysia was the Japanese occupation of Southeast Asia from 1942-1945. Japanese rule helped to invigorate a growing anti-colonial movement, which flourished following the British return after the war. When the British attempted to organize their administration of Malaya into one unit to be called the Malayan Union, strong Malay protests to what seemed to usurp their historical claim to the territory forced the British to modify the plan. The other crucial event was the largely Chinese communist rebellion in 1948 that remained strong to the mid-1950s. To address Malay criticisms and to promote counter-insurgency, the British undertook a vast range of nation-building efforts. Local conservatives and radicals alike developed their own attempts to foster unity among the disparate Malayan population. These grew into the Federation of Malaya, which gained independence in 1957. In 1963, with the addition of Singapore and the north Borneo territories, this federation became Malaysia. Difficulties of integrating the predominately Chinese population of Singapore into Malaysia remained, and under Malaysian directive Singapore became an independent republic in 1965.

National Identity. Throughout Malaysia's brief history, the shape of its national identity has been a crucial question: should the national culture be essentially Malay, a hybrid, or separate ethnic entities? The question reflects the tension between the indigenous claims of the Malay population and the cultural and citizenship rights of the immigrant groups. A tentative solution came when the Malay, Chinese, and Indian elites who negotiated independence struck what has been called "the bargain." Their informal deal exchanged Malay political dominance for immigrant citizenship and unfettered economic pursuit. Some provisions of independence were more formal, and the constitution granted several Malay "special rights" concerning land, language, the place of the Malay Rulers, and Islam, based on their indigenous status. Including the Borneo territories and Singapore in Malaysia revealed the fragility of "the bargain." Many Malays remained poor; some Chinese politicians wanted greater political power. These fractures in Malaysian society prompted Singapore's expulsion and produced the watershed of contemporary Malaysian life, the May 1969 urban unrest in Kuala Lumpur. Violence left hundreds dead; parliament was suspended for two years. As a result of this experience the government placed tight curbs on political debate of national cultural issues and began a comprehensive program of affirmative action for the Malay population. This history hangs over all subsequent attempts to encourage official integration of Malaysian society. In the 1990s a government plan to blend the population into a single group called "Bangsa Malaysia" has generated excitement and criticism from different constituencies of the population. Continuing debates demonstrate that Malaysian national identity remains unsettled.

Ethnic Relations. Malaysia's ethnic diversity is both a blessing and a source of stress. The melange makes Malaysia one of the most cosmopolitan places on earth, as it helps sustain international relationships with the many societies represented in Malaysia: the Indonesian archipelago, the Islamic world, India, China, and Europe. Malaysians easily exchange ideas and techniques with the rest of the world, and have an influence in global affairs. The same diversity presents seemingly intractable problems of social cohesion, and the threat of ethnic violence adds considerable tension to Malaysian politics.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

Urban and rural divisions are reinforced by ethnic diversity with agricultural areas populated primarily by indigenous Malays and immigrants mostly in cities. Chinese dominance of commerce means that most towns, especially on the west coast of the peninsula, have a central road lined by Chinese shops. Other ethnic features influence geography: a substantial part of the Indian population was brought in to work on the rubber plantations, and many are still on the rural estates; some Chinese, as a part of counter-insurgency, were rounded up into what were called "new villages." A key part of the 1970s affirmative action policy has been to increase the number of Malays living in the urban areas, especially Kuala Lumpur. Governmental use of Malay and Islamic architectural aesthetics in new buildings also adds to the Malay urban presence. Given the tensions of ethnicity, the social use of space carries strong political dimensions. Public gatherings of five or more people require a police permit, and a ban on political rallies successfully limits the appearance of crowds in Malaysia. It is therefore understandable that Malaysians mark a

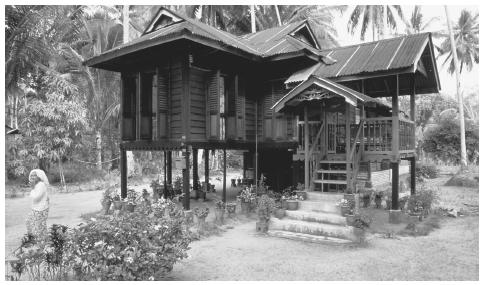

A house on Langkawi Island. Land ownership is a controversial issue in Malaysia, where indigenous groups are struggling to protect their claims from commercial interests.

sharp difference between space inside the home and outside the home, with domestic space carefully managed to receive outsiders: even many modest dwellings have a set of chairs for guests in a front room of the house.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Malaysia's diversity has blessed the country with one of the most exquisite cuisines in the world, and elements of Malay, Chinese, and Indian cooking are both distinct and blended together. Rice and noodles are common to all cuisine; spicy dishes are also favorites. Tropical fruits grow in abundance, and a local favorite is the durian, known by its spiked shell and fermented flesh whose pungent aroma and taste often separates locals from foreigners. Malaysia's affluence means that increasing amounts of meat and processed foods supplement the country's diet, and concerns about the health risks of their high-fat content are prominent in the press. This increased affluence also allows Malaysians to eat outside the home more often; small hawker stalls offer prepared food twenty-four hours a day in urban areas. Malaysia's ethnic diversity is apparent in food prohibitions: Muslims are forbidden to eat pork which is a favorite of the Chinese population; Hindus do not eat beef; some Buddhists are vegetarian. Alcohol consumption also separates non-Muslims from Muslims.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. When Malaysians have guests they tend to be very fastidious about hospitality, and an offer of food is a critical etiquette requirement. Tea or coffee is usually prepared along with small snacks for visitors. These refreshments sit in front of the guest until the host signals for them to be eaten. As a sign of accepting the host's hospitality the guest must at least sip the beverage and taste the food offered. These dynamics occur on a grander scale during a holiday open house. At celebrations marking important ethnic and religious holidays, many Malaysian families host friends and neighbors to visit and eat holiday delicacies. The visits of people from other ethnic groups and religions on these occasions are taken as evidence of Malaysian national amity.

Basic Economy. Malaysia has long been integrated into the global economy. Through the early decades of the twentieth century, the Malay peninsula was a world leader in the production of tin (sparked by the Western demand for canned food) and natural rubber (needed to make automobile tires). The expansion of Malaysia's industrialization heightened its dependence on imports for food and other necessities.

Land Tenure and Property. Land ownership is a controversial issue in Malaysia. Following the rubber boom the British colonial government, eager to placate the Malay population, designated portions of land as Malay reservations. Since this land could only be sold to other Malays, planters and speculators were limited in what they could purchase. Malay reserve land made ethnicity a state concern because land disputes could only be settled with a legal definition of who was considered Malay. These land tenure arrangements are still in effect and are crucial to Malay identity. In fact the Malay claim to political dominance is that they are bumiputera (sons of the soil). Similar struggles exist in east Malaysia, where the land rights of indigenous groups are bitterly disputed with loggers eager to harvest the timber for export. Due to their different colonial heritage, indigenous groups in Sarawak and Sabah have been less successful in maintaining their territorial claims.

Commercial Activities. Basic necessities in Malaysia have fixed prices and, like many developing countries, banking, retail, and other services are tightly regulated. The country's commerce correlates with ethnicity, and government involvement has helped Malays to compete in commercial activities long dominated by ethnic Chinese. Liberalization of business and finance proceeds with these ethnic dynamics in mind.

Major Industries. The boom and bust in primary commodities such as rubber and tin have given Malaysian society a cyclical rhythm tied to fickle external demand. In the 1970s the government began to diversify the economy (helped by an increase in oil exports) and Malaysia is now well on its way to becoming an industrial country. The country has a growing automotive industry, a substantial light-manufacturing sector (textiles, air conditioners, televisions, and VCRs), and an expanding high technology capacity (especially semi-conductors).

Trade. Malaysia's prominent place in the global economy as one of the world's twenty largest trading nations is an important part of its identity as a society. Primary trading partners include Japan, Singapore, and the United States, with Malaysia importing industrial components and exporting finished products. Palm oil, rubber, tropical hardwoods, and petroleum products are important commodities.

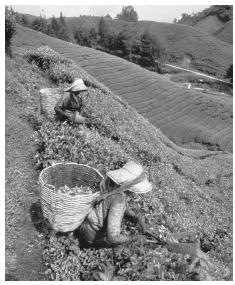

Division of Labor. The old ethnic division of labor (Malays in agriculture, Indians in the professions and plantations, and Chinese in mining and commerce) has steadily eroded. In its place, the Malaysian workforce is increasingly divided by class and citizenship. Educated urban professionals fill the offices of large companies in a multi-ethnic blend. Those without educational qualifications work in factories, petty trade, and agricultural small holdings. As much as 20 percent of the workforce is foreign, many from Indonesia and the Philippines, and dominate sectors such as construction work and domestic service.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. Class position in Malaysia depends on a combination of political connections, specialized skills, ability in English, and family money. The Malaysian elite, trained in overseas universities, is highly cosmopolitan and continues to grow in dominance as Malaysia's middle class expands. Even with the substantial stratification of society by ethnicity, similar class experiences in business and lifestyle are bridging old barriers.

Symbols of Social Stratification. In Malaysia's market economy, consumption provides the primary symbols of stratification. Newly wealthy Malaysians learn how to consume by following the lead of the Malay royalty and the prosperous business families of Chinese descent. A mobile phone, gold jewelry, and fashionable clothing all indicate one's high rank in the Malaysian social order. Given the striking mobility of Malaysian society, one's vehicle marks class position even more than home ownership. Most Malaysians can distinguish the difference between makes of cars, and access to at least a motor scooter is a requirement for participation in contemporary Malaysian social life. Kuala Lumpur has more motor vehicles than people. Skin color, often indicative of less or more time working in the hot tropical sun, further marks class position. Distinct class differences also appear in speech. Knowledge of English is vital to elevated class status, and a person's fluency in that language indexes their social background.

Political Life

Government. Malaysia's government is nominally headed by the king whose position rotates among the nine hereditary Malay rulers every five years. The king selects the prime minister from the leading coalition in parliament, a body which is further

Beginning in the 1970s, the government has attempted to increase the number of Malays living in urban areas like Kuala Lumpur (above).

divided into the elected representatives of the Dewan Rakyat and the appointed senators of the Dewan Negara. Since independence Malaysian national elections have been won by a coalition of ethnic-based political parties. Known first as the Alliance, and, following the 1969 unrest, as the National Front, this coalition is itself dominated by the United Malays National Organization (UMNO), a party composed of Malay moderates. UMNO rule is aided by the gerrymandered parliamentary districts that over-represent rural Malay constituencies. The UMNO president has always become Malaysia's prime minister, so the two thousand delegates at the biannual UMNO General Assembly are the real electoral force in the country, choosing the party leadership that in turn leads the country.

Leadership and Political Officials. Malaysian political leaders demand a great deal of deference from the public. The Malay term for government, kerajaan, refers to the raja who ruled from the precolonial courts. High-ranking politicians are referred to as yang berhormat (he who is honored), and sustain remarkable resiliency in office. Their longevity is due to the fact that successful politicians are great patrons, with considerable influence over the allocation of social benefits such as scholarships, tenders, and permits. Clients, in return, show deference and give appropriate electoral support. The mainstream press are also among the most consistent and most important boosters of the ruling coalition's politicians. Even with the substantial power of the political elite, corruption remains informal, and one can negotiate the lower levels of the state bureaucracy without paying bribes. However, endless stories circulate of how appropriate payments can oil a sometimes creaky process.

Social Problems and Control. Through its colonial history, British Malaya had one of the largest per capita police forces of all British colonies. Police power increased during the communist rebellion (the "Emergency") begun in 1948, which was fought primarily as a police action. The Emergency also expanded the influence of the police Special Branch intelligence division. Malaysia retains aspects of a police state. Emergency regulations for such things as detention without trial (called the Internal Security Act) remain in use; the police are a federal rather than local institution; and police quarters (especially in more isolated rural areas) still have the bunker-like design necessary for confronting an armed insurgency. Even in urban areas police carry considerable firepower. Officers with M-16s are not a rarity and guards at jewelry shops often have long-barrel shotguns. Criminals tend to be audacious given the fact that possession of an illegal firearm carries a mandatory death sentence. Since the police focus more on protecting commercial than residential property, people in housing estates and rural areas will sometimes apprehend criminals themselves. The most elaborate crime network is composed of Chinese triads who extend back in lineage to the colonial period. Malaysia is close to the opium producing areas of the "Golden Triangle" where Burma, Thailand, and Laos meet. Drug possession carries a mandatory death sentence.

Military Activity. The Malaysian military's most striking characteristic is that, unlike its neighbors, there has never been a military coup in the country. One reason is the important social function of the military to insure Malay political dominance. The highest ranks of the military are composed of ethnic Malays, as are a majority of those who serve under them. The military's controversial role in establishing order following the May 1969 urban rebellion further emphasizes the political function of the institution as one supporting the Malay-dominated ruling coalition. The Malaysian armed forces, though small in number, have been very active in United Nations peace-keeping, including the Congo, Namibia, Somalia, and Bosnia.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

The Malaysian government has promoted rapid social change to integrate a national society from its ethnic divisions. Its grandest program was originally called the New Economic Policy (NEP), implemented between 1971 and 1990 and continued in modified form as the National Development Policy (NDP). Since poverty eradication was an aim of the NEP a considerable amount of energy has gone to social welfare efforts. The consequences of these programs disseminate across the social landscape: home mortgages feature two rates, a lower one for Malays and a higher one for others; university admissions promote Malay enrollment; mundane government functions such as allocating hawker licenses have an ethnic component. But the government has also tried to ethnically integrate Malaysia's wealthy class; therefore many NEP-inspired ethnic preferences have allowed prosperous Malays to accrue even greater wealth. The dream of creating an affluent Malaysia continues in the government's 1991 plan of Vision 2020, which projects that the country will be "fully developed" by the year 2020. This new vision places faith in high technology, including the creation of a "Multi-Media Super Corridor" outside of Kuala Lumpur, as the means for Malaysia to join the ranks of wealthy industrialized countries, and to develop a more unified society.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

Through its welfare policies the government jealously guards its stewardship over social issues, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) work under its close surveillance. The state requires that all associations be registered, and failure to register can effectively cripple an organization. NGO life is especially active in urban areas, addressing problems peripheral to the state's priorities of ethnic redistribution and rapid industrialization. Many prominent NGOs are affiliated with religious organizations, and others congregate around issues of the environment, gender and sexuality, worker's rights, and consumers' interests.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. Malaysia's affluence has changed the gender divide in the public sphere of work while maintaining the gendered division

Young people are instructed at an early age to socialize primarily with kin.

of labor in the household. Most conspicuous among the new developments are the burgeoning factories that employ legions of women workers on the assembly lines. Domestic labor is a different matter, with cooking and cleaning still deemed to be female responsibilities. In wealthier families where both men and women work outside the home there has been an increase in hiring domestic servants. Since Malaysian women have other opportunities, nearly all of this domestic work goes to female foreign maids.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Generally men have more power than women in Malaysian society. Male dominance is codified in laws over such things as the guardianship of children. The top politicians, business leaders, and religious practitioners are predominately male. Yet Malaysian society shows considerable suppleness in its gender divisions with prominent women emerging in many different fields. Most of the major political parties have an active women's wing which provides access to political power. Though opportunities for men and women differ by ethnic group and social class, strict gender segregation has not been a part of modern Malaysian life.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Even with significant changes in marriage practices, weddings reveal the sharp differences in Malaysian society. There are two ways to marry: registering the union with the government; and joining in marriage before a religious authority. Christian Malaysians may marry Buddhists or Hindus answering only to their families and beliefs; Muslim Malaysians who marry non-Muslims risk government sanction unless their partner converts to Islam. Marriage practices emphasize Malaysia's separate ethnic customs. Indians and Chinese undertake divination rites in search of compatibility and auspicious dates, while Malays have elaborate gift exchanges. Malay wedding feasts are often held in the home, and feature a large banquet with several dishes eaten over rice prepared in oil (to say one is going to eat oiled rice means that a wedding is imminent). Many Chinese weddings feature a multiple-course meal in a restaurant or public hall, and most Indian ceremonies include intricate rituals. Since married partners join families as well as individuals, the meeting between prospective in-laws is crucial to the success of the union. For most Malaysians marriage is a crucial step toward adulthood. Although the average age for marriage continues to increase, being single into one's thirties generates concern for families and individuals alike. The social importance of the institution makes interethnic marriage an issue of considerable stress.

Domestic Unit. Malaysian households have undergone a tremendous transformation following the changes in the economy. The shift from agricultural commodities to industrial production has made it difficult for extended families to live together. Yet as family mobility expands, as a result of modern schedules, efforts to maintain kin ties also increase. Improved telecommunications keep distant kin in contact, as does the efficient transportation network. A dramatic example of this occurs on the major holidays when millions return to hometowns for kin reunions.

Inheritance. The critical issue of inheritance is land. With the importance Malays place on land ownership, it is rarely viewed as a commodity for sale, and the numerous empty houses that dot the Malaysian landscape are testament to their absentee-owners unwillingness to sell. Gold is also a valuable inheritance; Malaysians from all groups readily turn extra cash into gold as a form of insurance for the future.

Kin Groups. The crucial kin distinctions in Malaysian culture are between ethnic groups, which tend to limit intermarriage. Among the majority of Malays, kin groups are more horizontal than vertical, meaning that siblings are more important than ancestors. Those considered Malay make appropriate marriage partners; non-Malays do not. These distinctions are somewhat flexible, however, and those that embrace Islam and follow Malay customs are admitted as potential Malay marriage partners. Greater flexibility in kinship practices also appears among immigrant groups amid the fresh possibilities created by diasporic life. A striking example is the Baba community, Chinese who immigrated prior to British rule and intermarried with locals, developing their own hybrid language and cultural style. These dynamics point to the varied kinship arrangements possible between the different ethnic communities in Malaysian society.

Socialization

Infant Care. Malaysian babies are lavished with considerable care. Most are born in hospitals, though midwives still provide their services in more remote areas. Careful prohibitions are rigidly followed for both the infant and the mother, according to the various cultural customs. New mothers wear special clothes, eat foods to supplement their strength, and refrain from performing tasks that might bring bad luck to their babies. Grandmothers often live with their new grandchildren for the first few months of their new life.

Child Rearing and Education. Malaysian child rearing practices and educational experiences sustain the differences among the population. Most Malaysian children learn the importance of age hierarchy, especially the proper use of titles to address their elders. The family also teaches that kin are the appropriate source of friendly companionship. The frequent presence of siblings and cousins provides familiarity with the extended family and a preferred source of playmates. In turn, many families teach that strangers are a source of suspicion. The school experience reinforces the ethnic differences in the population, since the schools are divided into separate systems with Malay-medium, Mandarin-medium, and Tamil-medium instruction. Yet the schools do provide common experiences, the most important of which is measuring progress by examination, which helps to emphasize mastery of accumulated knowledge as the point of education. Outside of school, adolescents who mix freely with others or spend significant time away from home are considered "social," a disparaging remark that suggests involvement in illicit activity. A good Malaysian child respects

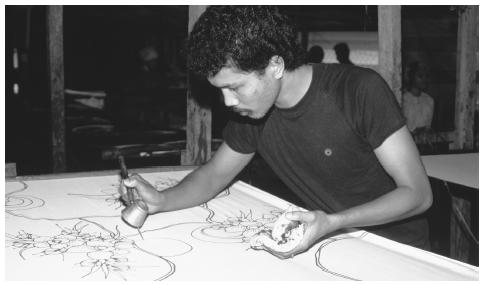

A textile worker creates a batik in Kota Bharu. Outside of northern peninsular Malaysia, batik designs are usually produced in factories.

hierarchy, stays close to kin, follows past examples, and is demure among strangers. These lessons teach Malaysian children how to fit into a diverse society.

Higher Education. Higher education is a vital part of Malaysian life, though the universities that are the most influential in the society are located outside the country. Hundreds of thousands of students have been educated in Britain, Australia, and the United States; the experience of leaving Malaysia for training abroad is an important rite of passage for many of the elite. Malaysia boasts a growing local university system that supplements the foreign universities. The quality of local faculty, often higher than that of the second- and third-tier foreign universities that many Malaysians attend, is rarely sufficient to offset the cachet of gaining one's degree abroad.

Etiquette

Malaysian society is remarkable due to its openness to diversity. The blunders of an outsider are tolerated, a charming dividend of Malaysia's cosmopolitan heritage. Yet this same diversity can present challenges for Malaysians when interacting in public. Because there is no single dominant cultural paradigm, social sanctions for transgressing the rights of others are reduced. Maintaining public facilities is a source of constant public concern, as is the proper etiquette for driving a motor vehicle. Malaysian sociability instead works through finding points of connection. When Malaysians meet strangers, they seek to fit them into a hierarchy via guesses about one's religion (Muslims use the familiar Arabic greetings only to other Muslims); inquiries into one's organization (as an initial question many Malaysians will ask, "who are you attached to?"); and estimations of age (unknown older men are addressed by the honorific "uncle," women as "auntie" in the appropriate language). Strangers shake hands, and handshaking continues after the first meeting (Malays often raise the hand to their heart after shaking), though it is sometimes frowned upon between men and women. Greetings are always expressed with the right hand, which is the dominant hand in Malaysian life. Since the left hand is used to cleanse the body, it is considered inappropriate for use in receiving gifts, giving money, pointing directions, or passing objects.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Nearly all the world religions, including Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Christianity are present in Malaysia. Religion correlates strongly with ethnicity, with most Muslims Malay, most Hindus Indian, and most Buddhists Chinese. The presence of such diversity heightens the importance of religious identity, and most Malaysians have a strong sense of how their religious practice differs from that of others (therefore a Malaysian Christian also identifies as a non-Muslim). Religious holidays, especially those celebrated with open houses, further blend the interreligious experience of the population. Tension between religious communities is modest. The government is most concerned with the practices of the Muslim majority, since Islam is the official religion (60 percent of the population is Muslim). Debates form most often over the government's role in religious life, such as whether the state should further promote Islam and Muslim practices (limits on gambling, pork-rearing, availability of alcohol, and the use of state funds for building mosques) or whether greater religious expression for non-Muslims should be allowed.

Religious Practitioners. The government regulates religious policy for Malaysia's Muslims, while the local mosque organizes opportunities for religious instruction and expression. Outside these institutions, Islam has an important part in electoral politics as Malay parties promote their Muslim credentials. Hindu, Christian, and Buddhist clergy often have a presence in Malaysian life through cooperative ventures, and their joint work helps to ameliorate their minority status. Religious missionaries work freely proselytizing to non-Muslims, but evangelists interested in converting Muslims are strictly forbidden by the state.

Rituals and Holy Places. Malaysia's most prominent holy place is the National Mosque, built in the heart of Kuala Lumpur in 1965. Its strategic position emphasizes the country's Islamic identity. Countrywide, the daily call to prayer from the mosques amplifies the rhythm of Islamic rituals in the country, as does the procession of the faithful to fulfill their prayers. Reminders of prayer times are included in television programs and further highlight the centrality of Islam in Malaysia. Important holidays include the birth of the Prophet and the pilgrimage to Mecca, all of which hold a conspicuous place in the media. The month of fasting, Ramadan, includes acts of piety beyond the customary refraining from food and drink during daylight hours and is followed by a great celebration. Non-Muslim religious buildings, practices, and holidays have a smaller public life in Malaysia. Part of this is due to fewer believers in the country, and part is due to public policy which limits the building of churches and temples along with the broadcasting of non-Muslim religious services. The important non-Muslim holidays include Christmas, Deepavali (the Hindu festival of light), and Wesak day (which celebrates the life of the Buddha). The Hindu holiday of Thaipussam merits special attention, because devotees undergo spectacular rites of penance before vast numbers of spectators, most dramatically at the famous Batu Caves, located in the bluffs outside of Kuala Lumpur.

Death and the Afterlife. Malaysians have a strong interest in the metaphysical, and stories about spirits and ghosts whether told in conversation, read in books, or seen on television gain rapt attention. Many of these stories sustain a relationship with people who have passed away, whether as a form of comfort or of fear. Cemeteries, including vast fields of Chinese tombs marked with family characters and Muslim graves with the distinctive twin stones, are sites of mystery. The real estate that surrounds them carries only a modest price due to the reputed dangers of living nearby. Muslim funerals tend to be community events, and an entire neighborhood will gather at the home of the deceased to prepare the body for burial and say the requisite prayers. Corpses are buried soon after death, following Muslim custom, and mourners display a minimum of emotion lest they appear to reject the divine's decision. The ancestor memorials maintained by Chinese clans are a common site in Malaysia, and the familiar small red shrines containing offerings of oranges and joss sticks appear on neighborhood street corners and in the rear of Chinese-owned shops. Faith in the efficacy of the afterlife generates considerable public respect for religious graves and shrines even from non-adherents.

Medicine and Health Care

Malaysia boasts a sophisticated system of modern health care with doctors trained in advanced biomedicine. These services are concentrated in the large cities and radiate out in decreasing availability. Customary practitioners, including Chinese herbalists and Malay healers, supplement the services offered in clinics and hospitals and boast diverse clientele.

Secular Celebrations

Given the large number of local and religious holidays observed in Malaysia, few national secular celebrations fit into the calendar. Two important ones

Farm workers harvesting tea leaves. Ethnic division of labor, in which Malays work almost entirely in agriculture, has eroded in recent years.

include the king's birthday, and the nation's independence day, 31 August. The strong Malaysian interest in sports makes victories for the national team, especially in badminton, a cause for revelry.

The Arts and the Humanities

Support for the Arts. Public support for the arts is meager. Malaysian society for the past century has been so heavily geared toward economic development that the arts have suffered, and many practitioners of Malaysia's aesthetic traditions mourn the lack of apprentices to carry them on. The possibility exists for a Malaysian arts renaissance amid the country's growing affluence.

Literature. The pre-colonial Malay rulers supported a rich variety of literary figures who produced court chronicles, fables, and legends that form a prominent part of the contemporary Malaysian cultural imagination. Developing a more contemporary national literature has been a struggle because of language, with controversies over whether Malaysian fiction should be composed solely in Malay or in other languages as well. Though adult literacy is nearly 90 percent, the well-read newspapers lament that the national belief in the importance of reading is stronger than the practice.

Graphic Arts. A small but vibrant group of graphic artists are productive in Malaysia. Practitioners of batik, the art of painting textiles with wax followed by dying to bring out the pattern, still work in northern peninsular Malaysia. Batik-inspired designs are often produced in factories on shirts, sarongs, table cloths, or dresses forming an iconic Malaysian aesthetic.

Performance Arts. Artistic performance in Malaysia is limited by the state's controls over public assembly and expression. The requirement that the government approve all scripts effectively limits what might be said in plays, films, and television. The preferred performance genre in Malaysia is popular music, and concerts of the top Malay pop singers have great followings in person and on television. Musical stars from Bombay and Hong Kong also have substantial numbers of very committed fans, whose devotion makes Malaysia an overseas stop on the tours of many performers. The favorite Malaysian entertainment medium is television, as most homes have television sets. Malaysians watch diverse programming: the standard export American fare, Japanese animation, Hong Kong martial arts, Hindi musicals, and Malay drama. The advent of the video cassette and the Internet was made for Malaysia's diverse society, allowing Malaysians to make expressive choices that often defeat the state's censorship.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

Given the Malaysian government's considerable support for rapid industrialization, scientific research is high on the list of its priorities. Malaysian universities produce sophisticated research, though they are sapped for funds by the huge expenditure of sending students overseas for their degrees. Malaysian scientists have made substantial contributions in rubber and palm oil research, and this work will likely continue to increase the productivity of these sectors. Government monitoring of social science research increases the risks of critical scholarship though some academicians are quite outspoken and carry considerable prestige in society.

Bibliography

Alwi Bin Sheikh Alhady. Malay Customs and Traditions , 1962.

Amir Muhammad, Kam Raslan, and Sheryll Stothard. Generation: A Collection of Contemporary Malaysian Ideas, 1998.

Andaya, Barbara Watson, and Leonard Y. Andaya. A History of Malaysia, 1982.

Ariffin Omar. Bangsa Melayu: Malay Concepts of Democracy and Community 1945-1950, 1993.

Carsten, Janet. The Heat of the Hearth, 1997.

Chandra Muzaffar. Protector? An Analysis of the Concept and Practice of Loyalty in Leader-Led Relationships within Malay Society, 1979.

Cheah Boon Kheng. Red Star Over Malaya, 1983.

Collins, Elizabeth. Pierced by Murugan's Lance: Ritual, Power, and Moral Redemption Among Malaysian Hindus, 1997.

Crouch, Harold. Government and Society in Malaysia, 1996.

Gomez, Edmund Terence and K. S. Jomo. Malaysia's Political Economy: Politics, Patronage, and Profits, 1997.

Gullick, John. Indigenous Political Systems of Western Malaya, 1958.

Harper, Timothy. The End of Empire and the Making of Modern Malaya, 1999.

Jomo, K. S. A Question of Class: Capital, the State, and Uneven Development in Malaya, 1986.

Kahn, Joel S., and Francis Loh Kok Wah, ed. Fragmented Vision: Culture and Politics in Contemporary Malaysia, 1992.

Kaur, Amarjit. Economic Change in East Malaysia: Sabah and Sarawak Since 1850, 1998.

Khoo Boo Teik. Paradoxes of Mahathirism: An Intellectual Biography of Mahathir Mohamad, 1995.

Kratoska, Paul. The Japanese Occupation of Malaya: A Social and Economic History, 1998.

Loh, Francis K. W. Beyond the Tin Mines: Coolies, Squatters and New Villagers in the Kinta Valley, c. 1880–1980, 1980.

Means, Gordon. Malaysian Politics: The Second Generation, 1991.

Milner, Anthony. The Invention of Politics in Colonial Malaya: Contesting Nationalism and the Expansion of the Public Sphere, 1995.

Mohamed Noordin Sopiee. From Malayan Union to Singapore Separation, 1974.

Nagata, Judith. Malaysian Mosaic: Perspectives from a Poly-Ethnic Society, 1979.

Ong, Aihwa. Spirits of Resistance and Capitalist Discipline: Factory Women in Malaysia, 1987.

Rehman Rashid. A Malaysian Journey, 1993.

Roff, William. The Origins of Malay Nationalism, 1967.

Shamsul, A. B. From British to Bumiputera Rule: Local Politics and Rural Development in Peninsular Malaysia, 1986.

Stenson, Michael. Class, Race, and Colonialism in West Malaysia: The Indian Case, 1980.

Strauch, Judith. Chinese Village Politics in the Malaysian State, 1981.

Sweeney, Amin. A Full Hearing: Orality and Literacy in the Malay World, 1987.

Tan Chee Beng. The Baba of Melaka: Culture and Identity of a Chinese Peranakan Community in Malaysia, 1988.

Winzeler, Robert L., ed. Indigenous Peoples and the State: Politics, Land, and Ethnicity in the Malayan Peninsula and Borneo, 1997.