Culture of Macau

Culture Name

Macanese

Alternative Names

Macao, Aomen, Haijing Ao

Orientation

Identification. Macau is a city in southern China's Guangdong province, and was until 20 December 1999 an overseas Portuguese territory, founded in 1557. It is now a special administrative region within the People's Republic of China, which agreed to recognize the city's special social and economic system for a period of fifty years.

Macau's status as an outpost of European settlement and commerce in China and its air of isolation gave it a special historical identity. Its population, while politically dominated by the Portuguese and their descendants, was always marked by an admixture of groups and by a steady influx of Chinese migrants. Since the early nineteenth century the majority of the population was Chinese. Macau was located on the old "silk route" and emerged as a major entrepôt (intermediary) trading center in Southeast Asia in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The name Macau is derived from the Chinese A-ma-gao Bay of A-Ma. A-ma was the name of a Chinese goddess, popular with the Chinese seafarers and fishermen who had a temple on the peninsula when the Portuguese first anchored there in 1513.

As a creation of the Portuguese, Macau represents a peculiar blend of Oriental and Western influences. This has given rise to a unique and hybrid urban culture, which gives the city an air of romance and nostalgia. At present, it is a rich commercial and industrialized city. Macau also has a reputation, dating from the 1920s and 1930s, as a place of smuggling, gambling, prostitution, and crime controlled by Chinese "triads" (crime syndicates). Macau's gambling houses were (and are) famous across Asia and still form a popular (Chinese) tourist destination.

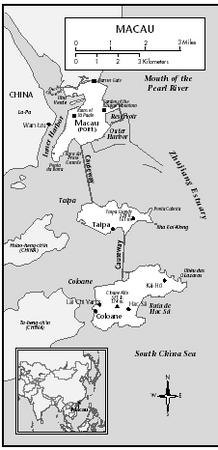

Location and Geography. Macau is located on a small peninsula and lies at the western shore of the great Pearl River Delta, opposite Hong Kong. Together with its two islands, Taipa and Coloane (connected to the peninsula by large bridges), it measures only some 8.5 square miles (22 square kilometers). Before inclusion into China in December 1999, Macau was separated from the mainland by the Barrier Gate (Portas do Cêrco) frontier. The city has good air links, and ferry and hydrofoil service to the neighboring islands, the mainland, and Hong Kong. A large international airport was opened in 1995.

There is no flora and fauna to speak of, as buildings have filled up most of the available space, and most primeval forest was used for construction and industrial purposes. Some pine forest remains on Coloane. In the late twentieth century significant land reclamation projects were carried out around the peninsula, creating space for new housing and industries, thus doubling the surface area of the city. The climate of Macau is subtropical and humid.

Demography. The city's population is about 465,000 (1999), with 95 percent ethnic Chinese. The Portuguese comprise about 3 percent of the population, with the rest including other Europeans, Indians, and various other groups, such as Filipinos. Immigration from China's mainland has always been significant, fueled by the opportunities of Macau's international trade and dynamic urban economy (especially in the twentieth century there was an exponential growth of immigration). At present, population growth is about 1.8 percent annually. Fertility (1.27 children per woman) is low according to Asian standards. Almost 50 percent of the ethnic Chinese population was born outside

Macau

Macau, but about 90 percent of the Portuguese were born in Macau.

Linguistic Affiliation. Indigenous languages spoken are Chinese-Cantonese (Yue dialect and Min dialects, about 96 percent of the population) and Portuguese (about 4 percent). Beijing-Chinese (Putonghua dialect) is a second language and growing in influence (for example, it is used in education). English is also expanding as a language in commerce and tourism. The old Macanese language (Patuá, or Makista) was a typical Creole language, based on Portuguese but heavily influenced by various Chinese dialects and by Malay. It has now virtually died out.

Symbolism. The coat of arms of Macau shows two angels around a shield with a crown, one holding a cross and one holding a globe. Beneath is the motto; "City of the Name of God, there is none more loyal," which refers to Macau's Catholic identity and bond with the Portuguese motherland. What the status of this coat of arms will be under Chinese rule is unclear.

As unofficial emblems or symbols of the town one might see the casino as the emblem of "modernity" (giving the city its main income), and the lone facade of Saint Paul's Cathedral as an apt symbol of Macau's past. This façade, a typical Portuguese structure, is the only remnant of an impressive Catholic church destroyed by fire in the eighteenth century. It may symbolize the near token presence of Portuguese culture in a now predominantly Chinese city that owes the larger part of its wealth to the Chinese fascination with gambling and to the efforts of Chinese businessmen and laborers.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. Although Portuguese sailors first anchored in 1513 and started using the peninsula for provisioning, Macau as a town was founded in 1557. It was a fixed point on the trade route to the Far East.

Macau always self-consciously maintained its bond with Portugal, even in times of war and turbulence. Religious identity played a great part in this. The city was a foothold for the Jesuits in their efforts to spread the gospel in Japan and China, though without much success. Beginning in the sixteenth century, other groups such as British Protestants, Japanese, and Indians also settled in Macau in small numbers.

Macau thus emerged as a Portuguese colonial settlement with a European-Christian identity, but as a result of its allowing Chinese immigration and settlement from early on, acquired a mixed character. Due to its open, commercial character and its weak military position vis-a`-vis China, there was never any exclusivist policy or national identity, though its political adherence was to Portugal.

Macau-Chinese relations were occasionally tense but never violent. Macau's historical status contrasts with that of Hong Kong, which was forced by Britain from China in an unfair treaty and under the threat of violence.

In 1887, Portugal by treaty received full sovereignty over Macau from China. This was reversed exactly one century later by a new treaty, ceding Macau to China.

National Identity. Macau is a peculiar amalgam of Portuguese and Chinese culture. This is evident in its rich and remarkable architecture, economic activities, and demography, as well as its political culture. Imperial, and later communist, China never gave up its claims to Macau as ultimately a part of China, but its relations toward Macau (and the Portuguese-Macanese attitude toward the Chinese) were marked by pragmatism, laissez-faire, and cooperation, a policy that was in tune with Macau's exceptional position as a hub of economic and commercial activity on the frontier of two worlds. The Chinese in Macau never clamored for inclusion into China (indeed, many came to Macau from the mainland as political and economic refugees) but did not protest when it became inevitable. They acquired, however, a distinguishable identity as Macanese-Chinese visa`-vis the rest of China's people, though this will inevitably fade after the handing over of Macau.

Ethnic Relations. Ethnic relations in Macau, though hierarchical and rooted in a colonial relationship, developed into a largely harmonious and relaxed pattern. Major tensions did occur when China interfered in the internal affairs of the city, as happened occasionally in the nineteenth century and in 1966, during the Cultural Revolution, when there were Chinese-inspired pro-communist riots.

Throughout its history, Macau always received people from many places, either forced (slaves from Africa) or voluntary (Indians, Malay, Filipinos). It also was a hospitable place for refugees, as most evident before and during World War II, when the Japanese offensives drove some 160,000 people (mainly Chinese) to the city, and after 1949, when the communists took over in China.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

The old urban architecture of Macau is one of the most attractive features of the city. Macau was built by the Portuguese, but the Mediterranean-European designs were always given an Oriental slant in actual building, and the Chinese made their own contribution in the form of shrines, temples, and Chinese gardens. The combination has charmed almost all visitors to the place; Macau's historical old city, its churches, forts, statues, parks, monuments, and government palaces give the city a romantic

A woman working on a toy car. The toy industry plays a prominent role in Macau's economy.

character. But this unique architecture is now also under threat, because massive modernization, population growth, and urban renewal have led to the demolishing and crowding out of many old buildings and neighborhoods. Before and after the handover of Macau to China, several statues and landmarks disappeared (some of them were even shipped to Portugal). Macau is one of the most densely built-up urban areas in the world. Environmental pollution is a growing problem.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. The Macanese cuisine is a much-praised mixture of Portuguese and Mediterranean cooking with some Indian and African influence (as people from Portugal's African colonies also came to Macau). Chinese influence was not pervasive. Macanese cuisine is popular among the Chinese population, and also outside Macau's boundaries, such as in Hong Kong.

Basic Economy. Macau is a rich city, with per capita gross domestic product (GDP) of US$17,500. It was built on entrepôt trade, gambling, and port services. These activities are still very important, despite the fact that the city also has developed into a major industrial center. Of growing significance is Macau's role as a center of financial services, both legal and illegal. Its status as a free port, its low taxes, the absence of foreign exchange controls, its flexible corporate laws, and its long experience in commerce and financial dealing make it an ideal place for uncontrolled, often criminal business schemes. Its relaxed system of governance has traditionally condoned this. There is a large "informal" unregistered sector.

Macau's economy has always been strongly dependent on ties with China and especially Hong Kong. Macau imports virtually all its food items (and even its water) from the Chinese mainland. China in turn derives great benefit from Macau, using it as a gateway to the capitalist world through which it imports and launders huge sums of unregistered money. This aspect of Macau's economy makes it a growing concern for global financial institutions and for the United States, which has identified Macau as a major center of money laundering and financial crime. Organized crime groups have a significant, but not clearly recorded, hold on Macau's economy. Corruption and bureaucratic red tape are a problem.

Land Tenure and Property. Most land is private property and owned by large business syndicates and individuals. Land prices are high due to great scarcity. The Chinese were allowed to acquire property in 1793. Since the 1920s there have been ongoing efforts at land reclamation, financed by both the government and private capital.

Commercial Activities. Macau's economy is based on commerce, import-export, tourism, and gambling (the latter accounting for about 25 percent of GDP), and expanding industrial production. Gambling brings in some 55 percent of the city government's revenue. Still, Macau has an aura of a city not only of casinos but also of shady business deals and financial crime. There are strong indications that China uses Macau as a major conduit of money laundering and unrecorded import-export transactions. Other tourist-related activities are horse, dog, and car races (the Grand Prix of Macau).

Major Industries. After the decline of its port, Macau succeeded in quickly reorienting its economy towards industrialization. Prominent industries include textiles, footwear, toys, incense, machinery, enamel, firecrackers, wooden furniture, Chinese wines, and electronic goods. Small and medium-sized businesses play a remarkably large role.

The tourism industry, centered around the twenty four-hour-a-day casinos, is of great importance, as are prostitution and racketeering. Through these activities the city had already become notorious in the late eighteenth century, with an upsurge in the 1920s and 1930s. Tourism declined somewhat in the late twentieth century.

Trade. International trade was the mainstay of Macau as a free port, and has been important until recently. Its first fortunes were made on the Europe-Japan trade route. Macau is a major importer of goods from China (food, textiles, clothing, electronics, and cheap consumer goods). Some of these are reexported.

Division of Labor. The Portuguese were active in the political administration, the higher civil service, and the army and police; the Macanese were mainly in the professions, in trade, and in some businesses; and the Chinese in business, casinos, fishing, crafts, manual labor, and other trade activities.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. Macau is largely a Chinese society, though significantly influenced by the specific urban culture and its Portuguese elite. During colonial times, there was a basic stratification in three groups: Portuguese (a small minority of "pure" Portuguese, often immigrants sent or appointed from Portugal), Macanese (a Creole group, some claiming descent from the original Portuguese-Malay unions), and Chinese (within this group there was a complex substratification). There was a prestige ranking of these groups and a certain amount of ethnic-"racial" prejudice, evident at critical social moments, such as choosing a marriage partner.

Economically speaking, the Portuguese were the original dominant class in Macau, although the Chinese, by virtue of their business success and connections with the mainland, soon came to form a powerful stratum. Following the December 1999 handover, the Portuguese political elite has been receding from the administration and government services. Chinese are becoming more prominent in the leading strata of Macanese society. The Portuguese have seemed to close their ranks, although the Macanese are in a more vulnerable position due to the pull of Chinese culture. Business and financial institutions are largely controlled by a small Chinese elite. In Macau's strongly commercial-capitalist economy there is a definite class structure based on wealth and business interests.

Symbols of Social Stratification. Dress, diet, and leisure activities distinguished the various groups from each other. According to social and community background (Portugese, Chinese and Macanese), people of the city visibly differentiate themselves by their religious behavior, leisure activities, and manner of dress, but wealth and social status have cut across any easy "ethnic" identification. Elite groups tend more to resemble each other, sharing smart western clothing, choice of the better residential areas, and leisure activities like attending horse and greyhound races and clubs, literary-cultural activities, and international traveling. In terms of diet, Portugese and other culinary traditions have to some extent mingled in Macau, but their essentials remained distinct and are still a mark of difference if not "identity" among the various communities.

Political Life

Government. Until December 1999, Macau was ruled by a Portuguese governor, appointed from Lisbon, and assisted by a Legislative Assembly of twenty-three members (citizens and officials). One-third of these were directly elected by the populace, and the rest were either appointed or "chosen" by business interest groups. There was also a ten-member Consultative Council, an advisory body.

Under Chinese rule and the new Basic Law (a temporary constitution, promulgated by the China's National People's Congress in 1993, and instituted in Macau in 1999), there is a chief executive, chosen in a complicated procedure. The Legislative Assembly remained, and was by law accorded sole legislative power. In practice, however, the chief executive has the decisive role. The Basic Law also gave citizens a large number of civic, social, and economic rights. But there was no significant expansion of democratic political rights.

Portuguese law codes still are at the basis of Macau's legal system, and the judiciary is held to be independent. There is a three-tier court system topped by a Supreme Court.

Leadership and Political Officials. The last Portuguese-appointed governor was general Vasco J. Rocha Vieira. In December 1999, Edmundo Ho Hau-Wah (a prominent and well-connected businessman, educated in Canada) assumed the top post of chief executive of Macau. There are no political parties.

Social Problems and Control. There are problems of organized crime, prostitution, trafficking in women, gang wars, and financial crime. Such crimes as assault, rape, and burglary are rare, but kidnappings, stabbings, and homicides frequently occur in the criminal world of the competing triads. The legal environment of Macau is not tight enough to allow the effective combating of organized crime—the traditional attractiveness of the city (and its wealth) is explained by its record of condoning loopholes in economic and financial laws.

Military Activity. Macau was a fortified city, with its own Portuguese army and city forts, that were built in the seventeenth century after a 1622 Dutch naval attack and reinforced after Chinese and British threats to the city. The army was also active against Chinese pirates that infested the Pearl River Delta beginning in the late sixteenth century. In 1975 the military were withdrawn and an internal security force of forty-six hundred men took its place. Since the 1999 handover, a Chinese army garrison of one thousand has been stationed in Macau, but it officially has no role to play in internal security.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

Existing programs in this field—support for orphans, the handicapped, and the aged; refugee care; social work—all have their origins in Christian religions institutions and missionary societies. In addition to the Church foundations, the government has also developed social safety-net provisions.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

There are many cultural and nongovernmental organizations in Macau, devoted to charity, public monuments, heritage preservation, and cultural life. Some of these are financed by prominent businessmen.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. Women are more and more active in business (forming about 43 percent of the workforce), but are not well-represented in political life. Chinese women in particular are taking their place in public and business life.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Women and men are equal before the law, and in all private and public organizations must receive equal pay for equal work. In recent years, there were no court cases concerning sex discrimination. There are no significant social or cultural barriers to the participation

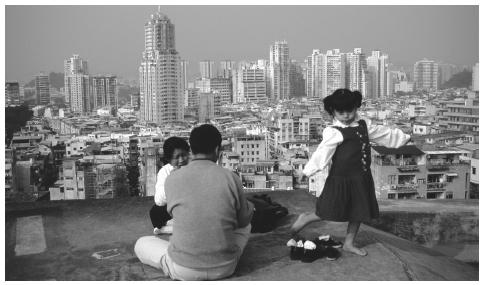

A family relaxing on a rooftop overlooking the cityscape. Despite continued Chinese dependence on larger, extended families, the nuclear family is most pervasive in Macau.

of women in society. Violence against women is not reported much. Among the Chinese and other Asian groups, women were subject to many more restrictions than among the Portuguese and other European groups, but this has changed due to economic developments.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. The three subcommunities of Macau— the Portuguese, Macanese, and Chinese—have traditionally intermingled, but as the population grew and the Chinese population became more predominant, intermarriage declined. The Portuguese and Macanese had formal monogamous marriage, while the Chinese also engaged in polygamous unions until the 1940s (depending on the economic situation of the husband). Weddings are important and costly occasions for celebration in both the Portuguese and Chinese communities.

Domestic Unit. Among the Chinese, the extended family, based on lineage connections, remains important; among Portuguese and Macanese, the nuclear family is the common domestic unit. Macau's capitalist economic development contributed to the nuclear family becoming the dominant form of domestic unit among all groups. In recent years, many young people live alone and/or marry late.

Inheritance. Inheritance still follows an adapted form of Portuguese law, but recognition is given to Chinese customary law on succession and family matters. Under Chinese rule, only laws approved by Macau's legislative and legal bodies are accepted, not Portuguese "imported" laws.

Kin Groups. Among the Chinese, lineage membership (with an emphasis on the father's side), and occasionally clan identity, remain important elements in social and ritual life. Lineages and extended kin (with some relatives often remaining in the Chinese area of origin) provided the moral framework of economic activity for the Chinese migrants. In Chinese business careers in Macau, the role of relatives on the mother's side has increased, indicating a development away from patrilineal orientation towards bilateral relationships: appealing to relatives from both father's and mother's as a resource.

Socialization

Infant Care. Children are cared for in the family tradition of their community. In the Chinese community, this means the extended family participates in child rearing.

Child Rearing and Education. Formal schooling is growing in importance as a framework of socialization. The school system is partly run by the government and partly in private hands (also subsidized by the city government). Education levels in Macau are still relatively low. About 25 percent of the population has secondary education, and less than 5 percent go to college. Education is compulsory up to only five years of primary school, though nine years of state education are provided free of charge. Parents show high levels of ambition for their children. There is an increasing demand for schooling, which has led to overcrowding. The overall literacy rate is about 90 percent (slightly less for women). About thirty thousand children (including many Chinese) are educated in Christian schools.

Higher Education. Higher education in Macau is well-developed, with two universities: the University of Macau (before 1991 called the University of East Asia) and the Macau Polytechnic. There are also various nonuniversity institutions, such as the Institute of Tourism Education, the Armed Forces College, and the International Institute of Software Technology.

Etiquette

Chinese culture emphasizes family integrity, lineage solidarity, reserved public behavior toward the powerful, and respect for parents and elder persons (that is, filial piety, or xiao ). These values are also largely maintained in Macau's urban culture. The Portuguese and the Macanese form relatively cohesive subsocieties of Catholics with their distinct values and preferences.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. According to 1996 census figures, a majority of the population (some 60 percent) claimed to have no religion. Buddhism is adhered to by some 17 to 20 percent of the population. There are minorities of Roman Catholics (7 percent), and of followers of Taoism and Confucianism (14 percent). There were also several popular Chinese spirit cults in Macau. Other religions such as Islam and Hinduism are adhered to by tiny minorities. In the late 1990s there also emerged a small but growing group of Falun Gong practitioners (although this is not considered a religion).

Notable in Macau's history is the great degree of tolerance and relaxed coexistence of the various religious communities. This is also reflected in the mixed architecture of the town, showing churches, temples, and other places of worship close to each other. The 1998 Religious Freedom Ordinance, which codified freedom of religion, is still in force after the handover to China.

Religious Practitioners. Macau has a Roman Catholic bishop and Buddhist dignitaries. The other religions do not have notable community leaders. Catholic and Buddhist officials often appear together at public functions in the city. Among the Chinese, many geomancers (i.e., diviners interpreting the [in]auspiciousness of lines and figures on the ground) are found.

Rituals and Holy Places. There are many churches and temples in Macau. The oldest religious structure is probably the Ma Kok Miu temple, dating back to a thirteenth century shrine. The most important churches are the Macau Cathedral, the Saint Joseph Seminary, and the Saint Laurence. Saint Paul's Church, of which only the facade remains, was built in the seventeenth century and was the largest church.

Death and the Afterlife. Attitudes toward death and belief in an afterlife differ according to the various religious doctrines. Many Chinese have domestic shrines for ancestor worship.

Medicine and Health Care

Medicine and health care are well-developed in Macau, with thirty-four hospitals and a doctor density of 1.5 per thousand inhabitants. The health-care system has its origins in Catholic Church institutions. There is a good disease- and epidemic-control system, which is important in a densely populated city with high rates of mobility. Health authorities are on alert for imported diseases brought by Chinese immigrants, such as hepatitis B and tuberculosis.

Secular Celebrations

The Chinese and Christian New Year are major holidays. An important Chinese festivity is the Dragon Boat festival.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. Before the handover, the city government designated Macau as a "city of culture.

Macau's urban architecture, as seen in Leal Senado Square (above), combines Portuguese and Chinese influences, which lend a romantic character to the city.

" It supported various arts foundations, such as the Fundação Macau and the Fundação Oriente. There are also private cultural foundations, such as the Instituto Português de Oriente. Since the mid-1990s, several new museums have opened, including the Chinese Robert Ho Tung Museum, the Luis de Camões Museum, and the Museum of Art. There is also a National Library. The tourist market and local people have created a demand for contemporary art.

Literature. There is a long Portuguese-Macanese literary tradition in the city, which likes to take inspiration from the myth that the famous seventeenth-century Portuguese poet Luis de Camões spent some time in Macau. The most famous writer in the Macau patois was José dos Santos Ferreira (d. 1993). Macau also inspired many local Chinese poets and authors (such as seventeenth-century poet Wu Li, and twentieth-century author Liang Piyun). The local Chinese and Portuguese literary traditions have remained relatively separate. Chinese Macanese literature is as a rule more political in content.

Graphic Arts. The Chinese graphic arts emerged as landscape painting, Chinese calligraphy, and book illustration. Some European painters (such as George Chinnery, d. 1852, and A. Borget, d. 1877) lived in Macau and depicted life and landscapes of Macau in many drawings, watercolors, and paintings. Notable local painters in nineteenth-century Macau were M. Baptista and Guan Qiaochang. Several Chinese painters in Macau show a creative mix of Chinese and European styles. There are also Portuguese-Macanese artists. The contemporary graphic arts scene (among both Portuguese and Chinese artists) is alive and well, supported by cultural foundations.

Performance Arts. In hotels and clubs one finds traditional Portuguese dance performances, fado singers, Chinese dance groups and foreign artists. The theater scene in Macau is relatively unimportant.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

The University of Macau is a notable center for technology studies, ICT, science and social studies. There is also the Inter-University Institute of Macau, which is active in ICT and technology studies. In the sciences, however, Macau stands in the shadow of Hong Kong, which has more institutions and research facilities.

Bibliography

Chaves, Jonathan. Singing of the Source: Nature and God in the Poetry of the Chinese Painter Wu Li, 1993.

Cremer, Rolf D., ed. Macau: City of Commerce and Culture, 2nd ed., 1991.

Batalha, Graciete Nogueira. Lingua de Macau, 1974.

Boxer, Charles R. "Macao as a Religious and Commercial Entrepôt in the sixteenth and seventeenth Centuries." Acta Asiatica, 26: 64–90, 1974.

——, ed. and trans. Seventeenth Century Macau in Contemporary Documents and Illustrations, 1984.

Gunn, Geoffrey C. Encountering Macau: A Portuguese City-State on the Periphery of China, 1557–1999, 1996.

Hing, Lo Shiu. Political Development in Macau, 1995.

Miu Bing Cheng, Christina. Macau: a Cultural Janus, 1999.

Porter, Jonathan. Macau: The Imaginary City, 1996.

Roberts, Elfed Vaughan, Sum Ngai Ling, and Peter Bradshaw. Historical Dictionary of Hong Kong and Macau, 1992.

Shipp, Steve. Macau, China: A Political History of the Portuguese Colony's Transition to Chinese Rule, 1997.