Culture of Libya

Culture Name

Libyan

Alternative Names

The Socialist Popular Libyan Arab Jamahiriya

Orientation

Identification. The Socialist Popular Libyan Arab Jamahiriya—literally, "state of the masses," is a nation that has been undergoing a radical social experiment over the last thirty years. This experiment has been underwritten by massive oil revenues and directed by the revolutionary government of Muammar Qaddafi.

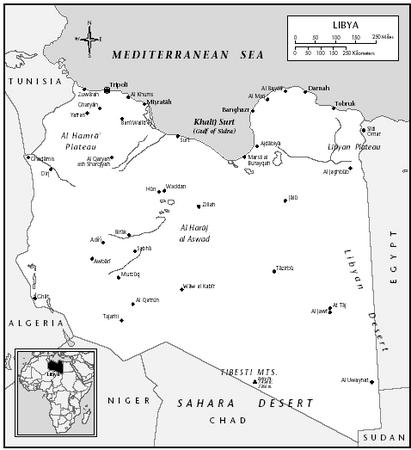

Location and Geography. Situated on the coast of North Africa, nearly all of the nation's land mass is within the Sahara Desert. The country is bounded to the north by the Mediterranean Sea, to the west by Tunisia and Algeria, and to the south by Chad and Niger. Egypt borders Libya to the east and Sudan is to the southeast. The landmass of 679,500 square miles (1,760,000 square kilometers) makes Libya the fourth largest country in Africa.

Each of the three provinces of Libya—Tripolitania on the western coast, Cyrenaica to the east, and Fezzan in the south—are influenced by the great Sahara in different ways. Tripolitania is sheltered by barrier mountains, the Jabal Nafusa, south of the coast. While the mountains create a favorable environment for agriculture, the coastal littoral, protected from the Sahara, is still arid and requires irrigation. The capital of Libya, Tripoli, is an oasis on the Tripolitanian coast and its inhabitants rely on aquifers to meet most of their water requirements. The coastal mountain range of Cyrenaica, the Jabal Akhdar, rises to a high plateau, which breaks precipitously down to the sea. There are five distinct ecological zones in this region, from a high plateau in the north to desert in the south, each with different combinations of pastoralism and agriculture. There are large towns in Cyrenaica, but until recently the nomadic Bedouins dominated the countryside.

The Gulf of Sirte is between eastern Tripolitania and the mountain chains in Cyrenaica. Primarily steppe country, it is suited to pastoral pursuits and historically has been a major seasonal grazing ground for some of the powerful tribes who spend winters in the interior of the desert.

South of the two mountain chains and the Gulf of Sirte lies the Sahara Desert and the province of Fezzan. The area is vast, extremely dry, and barren. It is characterized by large sand seas, eroded mountain ranges, and upland mesas. Aridity is a fact of existence in Libya. There is not a single permanent waterway in the whole country.

Permanent settlement in the south is limited to a number of depressions where irrigated agriculture may be pursued due to easily accessible supplies of fresh water from deep aquifers. These oases produce a wide variety of fruits and vegetables and support extensive date plantations. While these areas contain highly productive agricultural systems, they are restricted in population size due to the limitation on amounts of water available for irrigation.

Demography. This vast land has an extremely small population, estimated at 5.1 million in 2000, including approximately 163,000 non-nationals. The indigenous population is homogeneous, with 90 percent claiming to be of Arab ancestry. While largely rural, the massive oil wealth beginning in the 1960s changed the economic and residential profile of the population. For instance, between 1954 and l964, the citizen population of Tripoli grew by 58 percent, while Benghazi grew by 66 percent. A five-year plan introduced in the 1960s was geared to bring prosperity to rural areas. Its success slowed the migration to the urban areas and made paid employment widely available throughout the country. The oil industry brought large

Libya

numbers of European and North American workers to the country. Oil revenues allowed the state to greatly expand its work force while the wealth stimulated the private sector. Thus, over the years large numbers of guest workers have found their way to Libya from Eastern Europe and the surrounding Mediterranean and Arab states.

Linguistic Affiliation. The Bedouin invasion of North Africa in the eleventh century brought the Arabic language to Libya. In the western mountains of Libya, the Berber language is still spoken in places and remnants of it remain in the southern oases. Still, Libya is culturally homogeneous. Its citizens speak a distinctive dialect of Arabic in public while modern standard Arabic is taught in the schools and used in government and business. In culture, language, and religion, Libya forms a part of the greater Arab world.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. In Libya, as in most of the Middle East and North Africa, the modern concept of the territorially discreet nation is a recent development. Historically, Libya was characterized by sets of connections between relatively autonomous polities. Even under Turkish rule in the nineteenth century, the city of Tripoli was more of a city–state with commercial links to a politically autonomous countryside rather than a center of integrated rule. A large tented population of pastoral nomads, independent and aggressively autonomous, resided in the steppe and desert to the southeast and to the west. Smaller towns, some similar in commerce, trade, and political aspiration to Tripoli, occupied the shores of the Mediterranean to the west and east. The town of Misarata, with the support of the powerful Bedouin tribal allies of the Wafallah confederacy, challenged Tripoli's hegemony. To the south, the richly endowed agricultural communities of the Jabal Nafusa Mountains maintained an opposition to the coastal powers. With abundant rainfall and a temperate climate, crops were plentiful; citrus and olive groves abounded. Communities maintained independence, some supported by their kin among the powerful camel herding tribes to the south. Everyone was aware of the military prowess and political autonomy of the tribes.

Cyrenaica had a similar but more distinct antagonism between the desert and the town, and between pastoral tribal and sedentary agricultural society. Important towns like Ajadabya and Benghazi were isolated from a countryside occupied by Bedouin tribes who numbered over 90 percent of the province's population. The country was divided among the so-called noble tribes (i.e., landowners), all linked to one another through a common genealogical pedigree from a common ancestress, Sa-ada. In the south, there was a similar opposition between the oasis communities and the tribes.

Much of Libya was organized into agricultural centers surrounded by tribally-organized Bedouin nomads. There was no sense of nation; instead there was a series of social structures bound by the material conditions of trade in both practical and luxury goods. The only nineteenth-century institution that might be considered a defining characteristic of the country was the presence of a Turkish administration (the Porte). Even here the Porte was at a loss to exert its influence outside of the administrative centers.

The nascent strides toward a national identity began with the Italian invasion in the early twentieth century. The first Italian invasion in 1911 focused on the fertile coastal plain of Tripolitania and the city of Tripoli where political fragmentation gave the Italians an easy victory. Libyan allies were easy to gain if not to maintain. Having secured a foothold on the coast, the Italians mistakenly turned their attention to the Fezzan. They marched south through the Al Jufrah oases to Sebha, the modern capital of Fezzan, securing towns on their way. Once in Sebha, the tribes rallied, cut off the garrison and harassed the Italians as they tried to fight their way back to the coast. A decisive battle was fought in Sirte where the tribes under the Ulad Sleman defeated the Italians who then withdrew from the countryside.

In 1934, a more determined Italian force invaded. This time the primary opposition came from Cyrenaica where the tribes rallied under the banner of the Sanussi religious order and the leadership of such national heroes such as Umar al Mukhtar. A brutal and bloody ten-year guerilla war followed, pitting the modern military might of the Italians against a largely subsistence-based nomadic society. It is claimed that nearly 50 percent of the population of Cyrenaica perished during the struggle. The guerilla war represents an historic struggle in the minds of the Libyan people and its leader Umar al Mukhtar became Libya's first national hero.

The future king of Libya, Idris, the head of the Sanussi order (an ascetic Muslim sect), remained in exile during the colonial period, a symbol of regional if not national opposition to the Italians. He lent his support and that of his forces to the allied war effort in World War II, in exchange for a promise of national independence. The United Nations awarded Libya independence in 1951 and economic stability was assured by grants in aid from the United States and several European countries.

National Identity. In 1969, Libya underwent a revolution with far reaching consequences for the country both nationally and internationally. Muammar Qaddafi emerged as leader of the country. Under this regime, a series of far reaching social experiments have been tried, producing a somewhat unique political system. Internationally the pan-Arab and leftist leanings of the regime have had an impact, as the immense oil wealth of the country

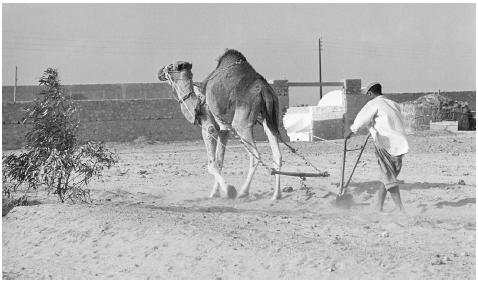

A man using a camel to plough a field along the Tunisia-Libya border.

has allowed the leadership a position on the international stage disproportionate to the country's size. The majority of Libyans have a pride in nation. The birth of the nation, the heroics of Umar al Mukhtar, and the 1969 revolution are commemorated in annual national celebrations as are the major religious events on the Islamic calendar.

Ethnic Relations. Although the Libyan people are in culture, language, and religion largely homogeneous, there have been and still are significant cultural minorities. Until the last half of the twentieth century there were relatively large Jewish and Italian communities in the country. Members of the Jewish community began to emigrate to Israel in 1948 and several anti-Israeli riots in 1948, 1956, 1967, and 1973 encouraged further emigration. In 1973, the revolutionary regime of Muammar Qaddafi confiscated all property owned by nonresident Jews. Also in 1973, Qaddafi's regime "invited" forty-five thousand Italian residents who remained from the Italian colonial era to leave the country, and all Italian properties were confiscated by the State.

Black Libyans are descendants of slaves brought to the country during the days of the slave trade. Some worked the gardens in the southern oases and on the farms along the coast. Others were taken in by Bedouin tribes or merchant families as retainers and domestics.

Berber peoples form a large, but less distinguishable minority in the Libyan population. The original inhabitants in most of North Africa, they were overrun in the eleventh and twelfth centuries by the Bedouin Arab armies of the expanding Islamic empire. Over the centuries, the Berber population largely fused with the conquering Arabs. Evidence of Berber culture still remains. The herdsmen and traders of the great Tuareg confederation are found in the south. Known as the "Blue Men of the Desert," their distinctive blue dress and the practice of men veiling distinguish them culturally from the rest of the population. Historically autonomous and fiercely independent, they stand apart from other Libyans and maintain links to their homelands in the Tibesti and Ahaggar mountain retreats of the central Sahara.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

Modern Libyan architecture throughout the country reflects the impact of the spectacular oil wealth. Modern apartment buildings and government and private office complexes abound in the major urban centers, while government (peoples') housing is a

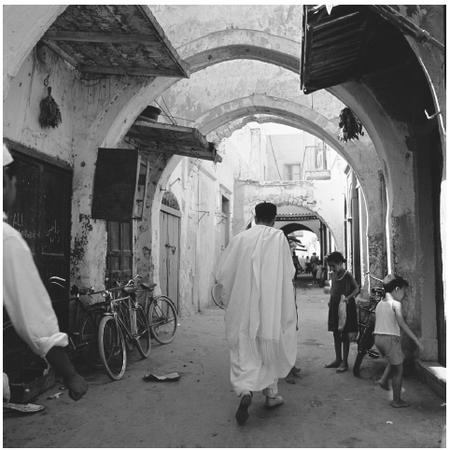

A man walking along a covered street in Tripoli. Walled fortifications dominate the old section of the city.

characteristic of the countryside. However, the distribution of political power among the sectors of Libyan society, to some degree, is reflected, still, in traditional forms of architecture. Walled fortifications, a testimony to tribal power as well as a reminder of the past as a piratical state, dominate the old section of Tripoli. Similar concerns for security characterized other ancient Libyan towns. In the mountains of Tripolitania, some settlements were constructed completely underground on hillsides. These towns of troglodytes maintained security by having only one entrance. Further south, the concern for defense also was a characteristic of architecture. Most oasis communities were walled and fortified. In the Sawknah oasis of Al Jufrah, for instance, the fortified wall extended around the entire residential area. There were only two gated entrances to the community, and the wall had parapets at intervals of twenty yards to allow defenders to catch the enemy in crossfire. In the center of the walled town stood a large fort whose ramparts commanded a line of fire on all sections of the outer wall. It stood as the last line and a sanctuary should the town be overrun. In many towns the traditional pattern of residence was a dense settlement of domestic units inside a fortified perimeter with agricultural lands lying at some distance from the residential areas.

Libyan towns are characterized by a strict distinction between public and private use of space. The streets, cafés, mosques, and shops are a man's world, while the domestic compound is the woman's world. The gardens, usually worked by families, are sanctuaries, not to be entered by strangers. The compact nature of fortified residential centers gives them a distinctive character. Streets are narrow and twisting. In some areas, kin groups, looking to extend the space available to developing extended families, have joined houses at the second-story level over the street to extend living quarters. This bridging effect produces long canopied cul-de-sacs, where kin groups may convert public to private space by gating the residential quarter. Whole communities may extend this concept of the privacy of space to the reception of strangers.

The use of space in relation to social distance is a major feature of Libyan custom. Public space is a busy, bustling, man's world. Private space is as rigidly defined for men as is public space for women. Traditional house design presents no windows at the first-floor level. Houses may have windows at the second-story level, but they are barred, sometimes with elaborate iron filigree. There is usually only one entrance, through a heavy wooden door. Some of the more luxurious homes have a large rectangular courtyard with elaborate gardens and fountains. The courtyard is completely enclosed, as is the private world of the immediate family. A wide balcony runs the full length and width of the second story and is accessed by one or two elegantly designed staircases. As the residence of a large extended family, rooms and apartments lead off from the center of the house on all sides and on both levels.

In the houses of prominent persons and local notables, another set of stairs is located immediately inside the front door without a view of the inner sanctuary of the courtyard. These stairs lead to the guestroom or marabour , a quasi-public space within the confines of the intensely private home. The head of the household entertains friends, business associates, clients, political supporters, and delegates in the marabour. Some of these rooms may accommodate as many as fifty guests. The marabour is almost always rectangular with mattresses lining the walls to provide seating and bedding for guests. Guests who are strangers are confined to this chamber and will not meet the women of the household.

In tented societies, spatial use and the distinction between public and private spaces are similar to that observed in the towns. Pastoral society has less of a problem defining public space. Bedouin camps consist of closely-related kin, and the physical distance between family groups in the same tribal section reinforces privacy. For most of the year, Bedouin camps spread across the countryside with groups separated from each other by several miles. Camps consist of discreet domestic units residing in tents that are placed in a single line.

Camps are organized to meet the complex demands of herd management and cottage industry. Individual male herd owners cooperate to accomplish the difficult task of managing several different herds with varied grazing and maintenance requirements. Male cooperation also extends to producing charcoal and to planting and harvesting cereal crops in years of plentiful rainfall. Women aid each other in weaving and spinning the wool and hair from the flocks; making tent tops, blankets, and storage bags; and milking and processing the products from the herds. Although members of the camp cooperate in daily activities, each married male member of the camp is an independent herd owner, with sons receiving their share of the family herd upon marriage.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Food in normal daily life reflects the simplicity of peasant and nomadic life styles. Libyan cooking styles are similar whether rural or urban, sedentary or nomadic. Main courses are almost always one–pot dishes. Couscous (cracked wheat), the national dish, is prepared in a spicy sauce of hot peppers, tomatoes, chick peas, and vegetables in season. All meals are eaten out of a communal bowl. Meals are of great symbolic importance; in the houses or the tents of prominent men, the major meal of the day rarely is taken without invited guests.

Most meals are frugal and simple with the daily consumption of meat kept to a minimum. The Bedouin rarely consume meat more than once a month. Agriculturists always seem to have adequate supplies of fruit, vegetables, and grain. Nomads have an abundance of milk, dates, and grain in most seasons. In both town and desert, meals are ended with three glasses of green tea, preparation and consumption of which is a distinct ritual.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Meals are prepared by the women of the household and served to guests by the young men of the household. Food is served on long low tables, tall enough to allow guests to sit cross legged and to belly up to the edge.

Meals served in the tented society vary slightly from presentation in towns. In tented society, important guests are honored with a sacrificial slaughter of a goat or sheep. In towns, sacrifice is not as frequent because there usually is easy access to daily markets. The animal is butchered, and the flesh is boiled to form the essential ingredient of a stew to be served over couscous . Sometimes various types of pasta may be used as a substitute for couscous . The main course usually is preceded by dried dates, milk, and buttermilk. Each liquid is served in a large communal bowl. Libyans drink green tea after all meals and throughout the day.

Lavish meals are prepared for almost all ritual occasions. Special and elaborate meals are prepared daily during the month of Ramadan when the daily fast is broken by a meal after sunset.

Basic Economy. The two major components of the traditional Libyan economy were agriculture and pastoralism, both largely subsistence activities. Most agricultural communities were kin-based, organized through patrilineal descent. Differences in wealth produced a class of local notables who relied upon the community for their influence and power. There was a tendency for communities to view themselves as corporate groups rather than agricultural communities or pastoral hinterlands. There were influential trading families in the larger commercial centers, but their power in the hinterland was limited. Communities tended to be self-contained and were based on subsistence activities in which families provided for most of their needs from their own labor. Surpluses were traded in local markets and exchanged in networks of pastoral families.

The economic specialization of pastoral and agricultural communities fostered cooperation as town and country sought each other's products. The Bedouin supplied the towns with meat, wool, hides, clarified butter, and security; markets in the towns provided necessary and luxury goods from artisans and traders (guns and ammunition) and agricultural products.

Land Tenure and Property. Traditionally, property was occasionally held communally, but most agricultural land was held privately. Land fragmentation led to a degree of local social stratification in which sharecropping developed. Generally, agriculture expanded onto marginal lands, mixing agriculture with herding. These communities were largely egalitarian, and less fortunate members of the community could count on support from their kinsmen.

In the pastoral realm, families owned their herds individually and secured land for grazing and watering rights as members of patrilineally-based corporations. Powerful tribes claimed ownership of discrete blocks of territory. A tribe is composed of a number of corporate land-owning groups who define relationships between themselves according to their relative position on the tribal genealogy. Tribal territory was subdivided between tribal sections following a genealogical charter. This charter of descent links the ancestors of the living corporate land-owning descent groups to each other in clearly defined measures of genealogical closeness or distance. Thus the members of one corporate landowning group see the members of an adjacent group as having rights to their territory by virtue of their descent from the brother of the founder of their own group.

Major Industries. Libya has been described as a "hydrocarbon state" since oil sales have an all pervasive role in the Libyan economy, politics, and social structure The discovery of oil in the late 1950s radically altered development and ushered in a period of massive economic redirection. In the first phase of exploration, the oil companies spent large sums and expenditures increased rapidly.

The first substantial oil revenues were paid to the government in 1962 and these revenues increased dramatically during the 1960s, providing rapid expansion in both the private and public sectors.

Two other industries that grew rapidly during the late 1950s and in the 1960s were construction and transportation. Construction, particularly in the cities, increased dramatically. Whole sections of Tripoli were built during this time. Construction was undertaken to provide suitable quarters for the many new local and foreign companies that grew in Libya. There also was an increase in construction of private dwellings in this period. New construction provided accommodations for the increased population and thriving business community in Tripoli.

Trade. Today, crude oil refined petroleum products and natural gas constitute nearly all Libya's exports, totaling $6 billion (U.S. dollars) in 1989. Major export partners were Italy, Germany, Spain, France, Sudan, and the United Kingdom. Major imports

Men gather with carts of melons near the Roman arch dedicated to Marcus Aurelius in Tripoli.

include machinery, transportation equipment, food, and manufactured goods. In 1989, Libya's major import partners were Italy, Germany, the United Kingdom, France, Tunisia, and Belgium.

Division of Labor. The increase in prosperity brought about a large-scale change in occupation. There was a major decline in persons working in agriculture but there was a sharp increase in laborers and clerical, sports and recreation, and transportation workers. The oil boom had massively changed the occupational and residential structure of the population in just a few years. In the countryside, the five-year plan of the 1960s ushered into existence a period of rural prosperity when many nomadic families became sedentary in order to take advantage of steady wage employment. A wide-scale patronage system developed that was administered through local political structures. Thus, "lamb barrel" politics, in a situation of radical economic change, reinforced family, lineage, tribal, and village structures. The traditional Libyan economy has continued to shrink as the oil economy has grown. By 1997, agriculture accounted for only 7 percent of the economic sector, while industry and services accounted for 47 percent and 46 percent respectively. But not even a revolution could dismantle the national lamb barrel.

Political Life

Government. On 1 September 1969, a group of army officers staged a successful bloodless coup that forced the king into exile and abolished the existing form of government. Muammar Qaddafi quickly emerged as the undisputed leader. The group of young officers considered themselves revolutionaries, but none of them had a background in revolutionary activity or schooling in radical politics. They aligned themselves with Gamal Abdul Nasser, leader of Egypt. Domestically, the conservative nature of the officers' policies became clear when they permanently closed nightclubs and prohibited the consumption of alcohol. They declared themselves to be socialist in politics and conservative in Islamic religious practices.

Once consolidated in power, the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC) undertook a series of radical initiatives to transform the economic, social, and political organization of Libya. Begun in 1973, this transformation was guided by the Green Book written by Qaddafi. The thesis of this book is a critique of participatory democracy in which it is argued that no man should represent another, but that the people should represent themselves directly. A contradictory argument of Qaddafi's is that the building blocks of society are family, tribe, and nation.

In the early 1970s, radical reform of the political process was undertaken to bring about direct participation of the people in the national democratic process. The municipalities in the country were reorganized territorially and their management was placed in the hands of locally elected peoples' committees. These committees were responsible for local government and the development of local budgets. Representatives of local committees presented budgets and other matters through a people's congress, which met once a year to discuss matters of concern and to deliver fiscal demands. This became one mechanism through which Libya redistributed some of the national wealth, and involved its citizens in a democratic process.

In 1975, a crisis developed in the ruling RCC and in the army concerning the course that the revolution should take. There was an attempted coup that was not successful; the army was purged and the RCC disbanded. The five remaining loyal RCC members were assigned to ministerial posts. Qaddafi,

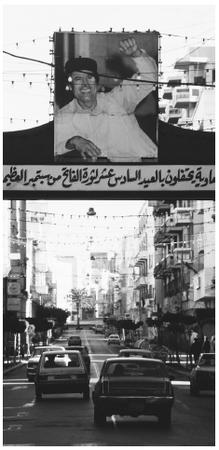

A Muammar Qaddafi banner hangs over a street in Tripoli. Qaddafi assumed leadership of Libya in 1969.

now firmly in control of the country, set a course that was enormously disruptive for the country and the international community.

Internally, Qaddafi unleashed the young zealots of the revolution, urging them to form revolutionary committees to instruct the people on the goals of the revolution. A rein of terror followed that was to last for over a decade. Revolutionary courts were soon established and nearly all institutions of government and commerce were put under the scrutiny of these committees. Only the institutions of banking and the oil industry were kept from their reach. Enemies of the revolution were ferreted out, tried secretly in revolutionary courts, jailed, tortured, and subjected to long prison sentences or death. Furor developed on the university campuses and on at least one occasion the student body witnessed the public hanging of fellow students who had been tried by students belonging to the revolutionary committee. There were numerous public hangings of citizens for crimes committed against the revolution, many of which were broadcast on national television. These measures were followed by other "reforms" which tore at the fabric of Libyan society. Private enterprise was abolished and all privately-owned shops were closed and replaced by government run Peoples' Markets. The regime nationalized all non-owner occupied housing and confirmed ownership on the occupants. Bureaucrats were sacked from government ministries and, in 1980, Qaddafi demonetized the currency, severely restricting the amounts of old money that citizens could convert to the new currency. There were reports of outraged citizens burning large piles of currency outside of the National Bank. These measures were adopted at a time when the world price for oil dropped severely, thus ushering in a decade of austerity in Libya. Qaddafi also canceled the stipends of thousands of Libyan students studying abroad and ordered them to return home. Many chose not to return and large numbers of citizens joined them in exile, most from the better-educated classes. By the mid 1980s, as many as 100,000 Libyans were living abroad, many joining political groups opposed to the revolution.

During the 1980s, the consequences of the revolution were being felt abroad. Qaddafi urged that revolutionary committees replace the diplomatic corps in Libyan embassies, renaming them "Peoples' Bureaus." In London a young female constable was shot dead outside the Peoples' Bureau where an anti-Qaddafi rally was under way. Qaddafi stepped up pressure on dissidents and called for the obligatory repatriation of all Libyan exiles. Noncompliance was to result in death. There were gang style executions of Libyan nationals in several European cities.

Internationally, Qaddafi played a controversial role. He fought a war with Chad, skirmished with Egypt, and trained a commando group which attacked a city in southern Tunisia. There were well-publicized financial contributions to Pakistan to aid in building the "Islamic Bomb," and to the Irish Republican Army, the Palestinian Liberation Organization, and other revolutionary organizations. There was also growing suspicion in the international community that the Qaddafi regime was involved directly in terrorism itself. These suspicions resulted in the United States and Britain severing diplomatic relations with Libya, putting in place severe economic sanctions and bombing the cities of Tripoli and Benghazi. Subsequently the Pan American Airline explosion over Lockerbie, Scotland was blamed on Libyan agents and the United Nations banned all air travel to Libya until the government was prepared to turn its agents over the Scottish government for trial. By late 1980s, Libya was thoroughly isolated by the international community.

This same period (1986–1987) marked a turning point in the revolution internally. The revolutionary committees were chastised for excesses. Qaddafi released prisoners from jail, personally supervising the destruction of one prison. He invited dissidents to return home without penalty; allowed citizens to travel freely, giving family members $1,000 (U.S.) each for the journey; and restored free enterprise. The liberalization has resulted in free market conditions with satellite dishes springing up everywhere, cell phones in use, and a full array of goods in the shops. But it does not appear that the liberalization has met with entrepreneurial fervor among the citizens. They seem to know that their mercurial government could change course at a moment's notice.

Libya has many characteristics which distinguish it organizationally from other states. Most importantly, the state does not rely upon taxation of its citizens for revenues. State budgets remain out of the realm of public discussion because those in power do not combine finance with politics. The central power seeks other means to gain compliance from its citizens. While direct democracy is a mechanism for distribution of some of the national wealth to the citizens, most of the national wealth remains to be used by those in power beyond public accountability. For instance, the budget for the military, one of the most important elements of Libya's new elite, is simply not published.

Military. The Libyan military has had a critical role in maintaining the Qaddafi regime in power. This support seems to have functioned from three perspectives. First, the military is extremely well funded. Although exact figures are difficult to obtain, Libya has spent at least $5 billion (U.S.) for military procurements every year since the late 1970s, with occasional military expenditures exceeding 40 percent of total government expenditures. The country spent $1,360 (U.S.) per capita in 1984. These figures are about twice the average per capita spending on defense for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and are rivaled only by Israel, Saudi Arabia, and a few oil rich Gulf Emirates. Second, these figures reflect an enormous procurement process in which the senior military seem to have profited greatly. There are accounts of senior officers living opulent life styles, building stately villas, and acquiring properties outside of normal channels. There is a suggestion here that Qaddafi has bought their loyalty. Third, there is hard evidence that tribalism has a role in the army. Qaddafi, during the revolutionary furor that he unleashed, appointed his family members as his bodyguards, trained his tribal kin as his elite army unit and, during the Revolutionary Committee period, appointed members of his tribe to the committee in the army. Thus opulent economic favor, nepotism, and tribal loyalty combined to assure that the most powerful institution in Libyan society continued to support the revolution and its leader.

Gender Roles and Statuses

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Purdah, the custom of secluding and veiling women, is a traditional feature of Libyan cultural life. Groups of veiled women are still found in markets in the company of kinsmen but they are infrequent visitors to mosques and absent entirely from café life. Women were traditionally placed in seclusion at puberty and appear in public veiled. They are only freed from this custom at menopause. The push toward female emancipation, as exhibited in the opening of public space to women, may be repealed at any time by either domestic male prerogative or national decree. Qaddafi established a military academy for females and, occasionally, has arrived at international meetings accompanied by female bodyguards dressed in battle fatigues.

Qaddifi claims that men and women are radically different in biology and nature. His view is that the nature of woman is to nurture and her role as mother and domestic is part of a natural order.

Where social life outside of the compound may be limiting for women due to the institution of purdah , within the household, the movements of women are not constrained. All are close kin and many are descendants of a common ancestor. As such they share a common daily social life. The movements of women are not restricted within the compound and both sexes may freely enter each other's abodes without invitation.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Descent kinship and marriage are major organizing factors in social, economic, and political life. Patrilineal descent defines group membership, while kinship is largely the product of marriage arrangements. Where the collective interests of descent groups are clearly defined, the patterns of kinship and marriage will reflect these interests. Marriages are arranged by the parents in consultation with members of the extended family and lineage. Libyan society, like much of the Arab world, places a premium on father's brother's daughter's marriage. This rule of "first right" is so important that in strongly-focused descent groups the male first cousin must waive his right to the girl before she is allowed to take a more socially distant spouse. Girls may marry at age fourteen, while men must usually wait until they are in their mid-to-late twenties. The age qualification for marriage between cousins thus restricts this form of marriage.

Approximately 20 percent of all marriages are "first right." Such arrangements give many descent groups a second set of social relationships. Since the father's brother's daughter's marriage removes the rule against group endogamy found in other societies, people are free to arrange marriages within the group outside the range of siblings and within generation. Thus, multiple strands of kinship crosscut group structure and further reinforce the corporate descent group.

Although groups may strive toward endogamy, other interests of the family and corporate group may lead to marriages being contracted between distant relations. In Bedouin society it is normal for groups to contract marriage with groups in distant ecological zones. Failure of the rains in one territory may lead to an invitation by more fortunate kin to visit and graze and water one's animals on their territory for the season.

Occasionally, there are marriages between the Bedouin and families of trading partners in oases. Marriages between adversaries in a feud may occur at the conclusion of the peace agreement. Marriages also are a way of binding groups in alliance since the offspring of successful unions will have close kin in two different groups. Thus marriage reflects family and group interests, and the patterns weave a web of mutual interest between families, lineages, and tribes.

Marriage arrangements require that siblings are married sequentially according to age. For a man to marry, he must be able to pay a "bride price" to the bride's family. Weddings may tax family resources because the more distantly related the bride, the

Libyans tending an urban vegetable patch.

higher the "bride price." Groups of brothers work together to gather the resources necessary for marriage. In Bedouin society, the resources used to marry come from the family herds. In towns, men contribute a portion of their pay to a brother's bride price.

Indications that in the urban areas some of the structures described above have been modified are manifest in several ways. Many women are now seen unveiled in public. A recent report now claims that there are more female than male university students. And the Qaddafi regime has prohibited the admission of foreign women into the country unaccompanied by senior male kinsmen, as the bride price for mail-order brides from surrounding Arab states is significantly less than for Libyan women. These suggestions of social transformation have not been adequately analyzed as yet.

Domestic Unit. The social makeup of Bedouin camps almost always consists of closely-related patrilineal relatives and their wives. A camp may consist of a large central tent housing a couple and their unmarried sons and daughters. Adjacent tents will house married sons and their wives and children. Occasionally a distant relative or friend and his family may join the camp for a season. In the line of tents, social solidarities are expressed by the proximity of tents in the line. Close kin, brothers, and fathers position their tents so that the tent pegs overlap and the guide ropes of the tents cross one another. The tent of a more remotely related member of the camp will be at the end of the line, a few yards from his neighbor, without guide ropes crossing.

Kin Groups. Descent groups with clearly-focused interests usually reside in contiguous residential structures, marry endogamously, cooperate in all social, economic, and political matters, and have a highly ramified social life within the group. For the most part, life is extremely comfortable.

The tribal land-owning corporations are themselves patrilineal descent groups or lineages whose members acquire rights by virtue of being the sons and daughters of a particular man. In theory all members of the group are patrilineal descendants of the founder. Members are said to be of one flesh and bone with equal rights to territorial resources. Equal rights also implies equal obligations. Members have the obligation to defend the territory against the encroachment of neighboring corporations. Liability is not an individual matter, but a matter between groups. Injury leads to a "state of feud" between groups in which all members of the offended group are required to take revenge against any male member of the offending group; this can lead to anarchy with a continual cycle of killings. Feuds have rules of conduct in which groups may decide to end the matter by a payment of a "blood price" whereby the offending group must compensate the offended group for the loss of life with payment. The members of the offending corporation must all contribute to the blood price, while all members of the offended group share in the compensation.

The institution of the feud makes possible a fairly orderly set of relations between competing groups where there are no institutions of government. While feuds may lead to peace through settlement, the relationships between groups defined through the genealogy will lead to a stand-off of equal numbers through opposition. The tribal segmentary system thus fosters an ethic of egalitarianism with its expression found in the members of the corporate patrilineal descent groups.

Nicknaming within tribes is prevalent as an expression of individual personality. The descent group is an institution that gives pride of place to its members, demands extreme loyalty of them, and provides a warm, nurturing support system to men and women of all ages.

The oil wealth has radically transformed the Libyan economy and its demography with widespread urbanization and wage employment. This process has only partially undermined traditional social structures as they were first reinforced by the pre-Revolutionary patronage system and then by the post-revolution political system. In the urban areas the constraints of family, lineage, and tribe have no doubt loosened. While the upper level bureaucrats—a second major section of the new elite—may answer to Qaddafi and his ruling clique, this is not true for the rural areas. There, ties of family, lineage, tribe, and residence still remain the dominant forms of organization. This striking feature of Libyan life is partially the result of the implementation of the political structures described by Qaddafi in the Green Book. Local committee members and bureaucrats are themselves members of local kin-based groups whose loyalty they must retain and whose wishes they must consider. While this is a society where immense oil wealth might lead to radical social transformation, in the rural areas, at least, this has not happened. There, cultural traditions have been slow to change as the political and economic institutions of government are refracted through family, lineage, and tribal interests.

Socialization

Higher Education. Libya has two universities, several technical schools, and a well developed primary and secondary school system. By the mid 1980s, there were 1,245,000 students enrolled in primary and secondary education: 54 percent were males and 46 percent were females. During this period the government claimed to have constructed 32,000 new classrooms while the number of teachers increased from about 19,000 to 79,000.

University enrollments also show dramatic increases from 3,000 students in 1969 to more than 25,000 during the 1980s with female enrollments numbering about 25 percent. Education is free and university students receive generous stipends. Even though large strides have been made in Libyan education, the country still lacks technical expertise in many areas. The military lacks the skilled personnel to adequately maintain its weapons systems. Most doctors, dentists, and pharmacists are foreign nationals, while 60 percent of Libya's top bureaucrats and 40 percent of the work force are expatriates.

Etiquette

A polite stranger, when approaching a camp, will pause about one hundred yards from the line of tents. A series of activities converting private into public space begins. Either one tent in the line will be vacated and converted into a guest tent, or the large tent of the oldest male will be divided down the middle to produce a guest compartment separated from the domestic section. Entertainment of guests in tented society is similar to towns. One difference in tented society is that a guest will not be asked his social identity until after the meal when the breaking of bread has placed the guest under his host's protection. This rule of sanctuary ensures that members of rival groups or those in a feuding relationship may travel the desert in relative safety.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Most traditional Libyans are devout Muslims and practice a simple and deeply personal religion. Adults follow the strictures of Islam; they pray five times a day, give alms to the poor, and fast for the month of Ramadan. There is a certain austerity to Libyan Islam shaped by the harshness of traditional life. This asceticism was reinforced by the Sanussi order, which was abolished by the Qaddafi regime for political reasons. In its place, the regime instituted fundamentalist practices with very little impact on rural life, where the Libyan version of an ascetic Islam is still practiced.

Religious Practitioners. The Ulama, or religious scholars, have been upstaged by the regime, but in the countryside mosques are well attended. The folk religion of the people subscribes, in part, to a deviation from traditional Islam. In Libya, as in other parts of North Africa, the cult of saints is highly developed. There are individual living saints, marabout , whose miracles are widely reported and whose services in a curative capacity are sought. People also visit the tombs of men of reputation, seeking cures for illness, success in business, and luck in passing an examination. There are small tribes whose members are said to have inherited baraka , the quality of goodness or holiness, and minister to local people. There are also lineages who are said to be descendants of the prophet Mohammed. They are given the title of sharif.

Bibliography

Allan, J. A. Libya. The Experience of Oil , 1981.

——. Libya Since Independence: Economic and Social Development , 1982.

Anderson, L. The State and Social Transformation in Tunisia and Libya , 1986.

Arnold, G. The Maverick State. Gaddafi and the New World Order , 1996.

Behnke, R. H., Jr. "The Herders of Cyrenaica: Economy and Kinship Among the Bedouin of Eastern Libya," Illinois Studies in Anthropology , 12; 1980.

Blundy, D. and A. Lycett. Qaddafi and the Libyan Revolution , 1987.

Cockburn, A. "Libya," National Geographic Magazine , March 2001: 2-32.

Cooley, J. K. Libyan Sandstorm: The Complete Account of Qaddafi's Revolution , 1983.

Dalton, W. G. "Economic Change and Political Continuity in a Saharan Oasis Community," Man , 1973.

——. "Lunch with Abdullah: An Account of Politics in the Fezzan Region of Libya." Proceeding of the African Studies Association, Brandeis University, 1978.

——. "Sedentarization of Nomads: The Libyan Case." In Salzman and Galaty, ed. Nomads in a Changing World , 1990.

Davis, J. Libyan Politics: Tribe and Revolution , 1987.

Evans-Pritcharsd, E. E. The Sanusi of Cyrenaica , 1949.

Farley, R. Planning for Development in Libya: The Exceptional Economy in the Developing Word , 1971.

El-Fathaly, O. and Palmer, M. "Institutional Development in Qaddafi's Libya." In Vanderwalle, D. ed., Qaddafi's Libya 1969-1994.

——. Political Development and Bureaucracy in Libya , 1997.

First, R. Libya: The Elusive Revolution , 1975.

Khadduri, M. Modern Libya: A Study in Political Development , 1963.

Khouri, P. and J. Kostiner eds. Tribes and State Formation in the Middle East , 1990.

Library of Congress. Libya , 1987.

National Salvation Front. Libya Under Qaddafi and the NFSL Challenge , 1992.

Pelt, A. Libyan Independence and the United Nations , 1970.

Peters, E. L. "Aspects of the Family Among the Bedouin of Cyrenaica," In M. F. Nomkoff, ed. Comparative Family Systems , 1965.

——. "Some Structural Aspects of the Feud Among the Camel-Herding Bedouin of Cyrenaica," Africa 37: 261-82, 1967.

——. "The Tied and the Free: An Account of a Type of Patron-Client Relationship Among the Bedouin Pastoralists of Cyrenaica." In J. G. Peristiany, ed. Contributions to Mediterranean Sociology 167-88, 1968.

——. "The Proliferation of Segments in the Lineages of the Bedouin of Cyrenaica." In L. M. Sweet, ed. Peoples and Cultures of the Middle East : 363-98, 1970.

Roumani, J. "From Republic to Jamahiriya: Libya's Search for Political Community," Middle East Journal 37 2: 151-68, 1983.

Vandewalle, D. Libya Since Independence , 1998.

Wright, J. Libya: A Modern History , 1982.