Culture of Kenya

Culture Name

Kenyan

Alternative Names

Jamhuri ya Kenya

Orientation

Identification. The country takes its name from Mount Kenya, located in the central highlands.

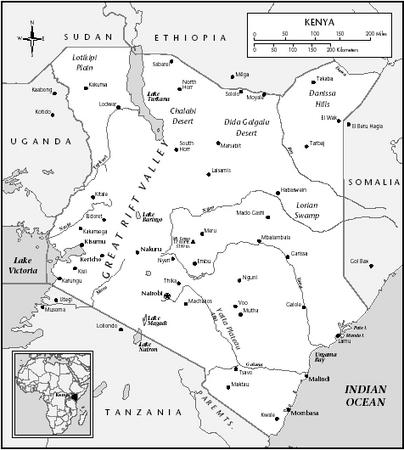

Location and Geography. Kenya is located in East Africa and borders Somalia to the northeast, Ethiopia to the north, Sudan to the northwest, Uganda to the west, Tanzania to the south, and the Indian Ocean to the east. The country straddles the equator, covering a total of 224,961 square miles (582,600 square kilometers; roughly twice the size of the state of Nevada). Kenya has wide white-sand beaches on the coast. Inland plains cover three-quarters of the country; they are mostly bush, covered in underbrush. In the west are the highlands where the altitude rises from three thousand to ten thousand feet. Nairobi, Kenya's largest city and capital, is located in the central highlands. The highest point, at 17,058 feet (5,200 meters), is Mount Kenya. Kenya shares Lake Victoria, the largest lake in Africa and the main source of the Nile River, with Tanzania and Uganda. Another significant feature of Kenyan geography is the Great Rift Valley, the wide, steep canyon that cuts through the highlands. Kenya is also home to some of the world's most spectacular wildlife, including elephants, lions, giraffes, zebras, antelope, wildebeests, and many rare and beautiful species of birds. Unfortunately, the animal population is threatened by both hunting and an expanding human population; wildlife numbers fell drastically through the twentieth century. The government has introduced strict legislation regulating hunting, and has established a system of national parks to protect the wildlife.Demography. According to an estimate in July 2000, Kenya's population is 30,339,770. The population has been significantly reduced by the AIDS epidemic, as have the age and sex distributions of the population. Despite this scourge, however, the birth rate is still significantly higher than the death rate and the population continues to grow.

There are more than forty ethnic groups in the country. The largest of these is the Kikuyu, representing 22 percent of the population. Fourteen percent is Luhya, 13 percent is Luo, 12 percent is Kalenjin, 11 percent Kamba, 6 percent Kisii, and 6 percent Meru. Others, including the Somalis and the Turkana in the north and the Kalenjin in the Great Rift Valley, comprise approximately 15 percent of the population. These ethnic categories are further broken down into subgroups. One percent of the population is non-African, mostly of Indian and European descent.

Linguistic Affiliation. The official languages are English and Kiswahili (or Swahili). Swahili, which comes from the Arabic word meaning "coast," is a mix of Arabic and the African language Bantu. It first developed in the tenth century with the arrival of Arab traders; it was a lingua franca that allowed different tribes to communicate with each other and with the Arabs. The major language groups native to the region include Bantu in the west and along the coast, Nilotic near Lake Victoria, and Cushitic in the north.

English is the language generally used in government and business. It is also used in most of the schools, although there has been movement towards using Kiswahili as the teaching language. English is not spoken solely by the elite, but only people with a certain level of education speak it.

Symbolism. The Kenyan flag has three horizontal stripes—red, black, and green—separated by thin

Kenya

white bands. The black symbolizes the people of Kenya, the red stands for the blood shed in the fight for independence, and the green symbolizes agriculture. In the center of the flag is a red shield with black and white markings and two crossed spears, which stands for vigilance in the defense of freedom.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. The Great Rift Valley is thought to be one of the places where human beings originated, and archeologists working in the valley have found remains of what they speculate are some of the earliest human ancestors. The first known inhabitants of present-day Kenya were Cushitic-speaking tribes that migrated to the northwest region from Ethiopa around 2000 B.C.E. Eastern Cushites began to arrive about one thousand years later, and occupied much of the country's current area. During the period from 500 B.C.E. to 500 C.E. , other tribes arrived from various parts of Africa. Tribal disagreements often led to war during this time.

In the 900s, Arab merchants arrived and established trading centers along the coast of East Africa. Over the ensuing eight centuries, they succeeded in converting many Kenyans to Islam. Some Arabs settled in the area and intermarried with local groups.

Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama landed at Mombasa in 1498, after discovering a sailing route around the Cape of Good Hope. The Portuguese colonized much of the region, but the Arabs managed to evict them in 1729. In the mid-1800s, European explorers stumbled upon Mount Kilimanjaro and Mount Kenya, and began to take an interest in the natural resources of East Africa. Christian missionaries came as well, drawn by the large numbers of prospective converts.

Britain gradually increased its domain in the region, and in 1884–1885, Kenya was named a British protectorate by the Congress of Berlin, which divided the African continent among various European powers. The British constructed the Uganda Railway, which connected the ports on Kenya's coast to landlocked Uganda. The increasing economic opportunities brought thousands of British settlers who displaced many Africans, often forcing them to live on reservations. The Africans resisted—the Kikuyu in particular put up a strong fight—but they were defeated by the superior military power of the British.

During the early twentieth century, the British colonizers forced the Africans to work their farms in virtual slavery, and kept the upper hand by making it illegal for the Kenyans to grow their own food. In the early 1920s, a Kikuyu named Harry Thuku began to encourage rebellion among his tribe and founded the East Africa Association. He was arrested by the British in 1922, provoking a popular protest. The British reacted violently, killing twenty-five people in what came to be called the Nairobi Massacre.

Desire for self-rule continued to build and in 1944 the Kenya African Union, a nationalist party, was founded. In 1946, the Kikuyu leader Jomo Kenyatta returned after sixteen years in England and began agitating for Kenyan independence. Back on his home soil, he was elected president of the

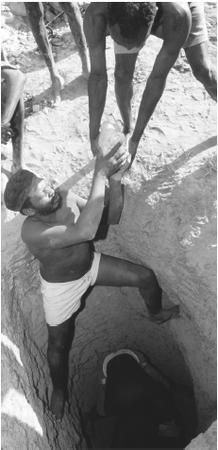

Turkana men working at a gold mine in northern Kenya pass blocks of gold-bearing ore to the surface of a shaft. The mines often lie sixty or so feet below the ground.

Kenya African Union. His rallying cry was uhuru, Swahili for freedom. While Kenyatta advocated peaceful rebellion, other Kikuyu formed secret societies that pledged to win independence for Kenya using whatever means necessary, including violence. In the early 1950s, members of these groups (called Mau Mau) murdered 32 white civilians, as well as 167 police officers and 1,819 Kikuyu who disagreed with their absolutist stance or who supported the colonial government. In retaliation for these murders, the British killed a total of 11,503 Mau Mau and their sympathizers. British policy also included displacing entire tribes and interning them in barbed-wire camps.

Despite Kenyatta's public denouncement of the Mau Mau, the British tried him as a Mau Mau leader and imprisoned him for nine years. While Kenyatta was in jail, two other leaders stepped in to fill his place. Tom Mboya, of the Luo tribe, was the more moderate of the two, and had the support of Western nations. Oginga Oginga, also a Luo, was more radical, and received support from the Soviet bloc. One common goal of the two was to give blacks the right to vote. In a 1957 election, blacks won their first representation in the colonial government and eight blacks were elected to seats in the legislature. By 1961, they constituted a majority of the body.

In 1960 at the Lancaster House Conference in London the English approved Kenyan independence, setting the date for December 1963. Kenyatta, released from prison in 1961, became prime minister of a newly independent Kenya on 12 December 1963 and was elected to the office of president the following year. Although he was a Kikuyu, one of Kenyatta's primary goals was to overcome tribalism. He appointed members of different ethnic groups to his government, including Mboya and Oginga. His slogan became harambee, meaning "Let's all pull together." In 1966, however, Oginga abrogated his position as vice-president to start his own political party. Kenyatta, fearing cultural divisiveness, arrested Oginga and outlawed all political parties except his own. On 5 July 1969, Tom Mboya was assassinated, and tensions between the Luo and the Kikuyu increased. In elections later that year, Kenyatta won reelection and political stability returned. Overall, the fifteen years of Kenyatta's presidency were a time of economic and political stability. When Kenyatta died on 22 August 1978, the entire nation mourned his death. The vice-president, Daniel Toroitich arap Moi (a Kalenjin of the Tugen subgroup) took over. His presidency was confirmed in a general election ninety days later.

Moi initially promised to improve on Kenyatta's government by ending corruption and releasing political prisoners. While he made some progress on these goals, Moi gradually restricted people's liberty, outlawing all political parties except his own. In 1982, a military coup attempted to overthrow Moi. The coup was unsuccessful, and the president responded by temporarily closing the University of Nairobi, shutting down churches that dissented from his view, and giving himself the power to appoint and fire judges. Moi did away with secret ballots, and several times changed election dates spontaneously to keep people from voting. Moi's opposition has faced even more blatant obstacles: Legislator Charles Rubia, who protested the policy of waiting in line to vote, was arrested and later lost his seat in a rigged election; Robert Ouko, Moi's Minister of Foreign Affairs, threatened to expose government corruption, and was later found with a bullet in his head, his body severely burned. Pro-democracy demonstrations in the early 1990s were put down by paramilitary troops, and leaders of the opposition were thrown in jail. Western nations responded by demanding that Kenya hold multi-party elections if they wanted to continue to receive foreign aid, and in December 1992 Moi won reelection, despite widespread complaints of bribery and ballot tampering. During this time, the economy floundered: inflation skyrocketed, the Kenyan currency was devalued by 50 percent, and unemployment rose.

In 1995, the various opposition groups united in an attempt to wrest the presidency from Moi and formed a political party called Safina. Opposition efforts have been unsuccessful so far, however. In July 1997, demonstrators demanding constitutional reforms were teargassed, shot, and beaten, resulting in eleven deaths.

Despite Moi's unpopularity and his advanced age (he was born in 1924), he maintains his grip on the presidency. Kenya continues to suffer from tribalism and corruption, as well as high population growth, unemployment, political instability, and the AIDS epidemic.

National Identity. Kenyans tend to identify primarily with their tribe or ethnic group, and only secondarily with the nation as a whole. The Kikuyu, who were better represented in the independence movement than other groups, and who continue to dominate the government, are more likely to identify themselves as Kenyans.

Ethnic Relations. The Kikuyu are the largest tribe in the highlands, and tend to dominate the nation's politics. Over the centuries, they consolidated their power by trading portions of their harvests to the hunter-gatherers for land, as well as through inter-marriage. This gradual rise to domination was peaceful and involved a mingling of different ethnic groups. While the Kikuyu have enjoyed the most power in the post–independence government, they were also the hardest–hit by brutal British policies during the colonial period. The Kikuyu traditionally had an antagonistic relationship with the Maasai, and the two groups often raided each other's villages and cattle herds. At the same time, there was a good deal of intermarriage and cultural borrowing between the two groups. Relations among various other ethnic groups are also fraught with tension, and this has been a major obstacle in creating a united Kenya. These conflicts are partly a legacy of colonial rule: the British exaggerated ethnic tensions and played one group against another to reinforce their own power. Under British rule, different ethnic groups were confined to specific geographic areas. Ethnic tensions continue to this day, and have been the cause of violence. In the early 1990s tribal clashes killed thousands of people and left tens of thousands homeless. Conflicts flared again in the late 1990s between the Pokots and the Marakwets, the Turkanas and the Samburus, and the Maasai and the Kisii.

Kenya has a fairly large Indian population, mostly those who came to East Africa in the early twentieth century to work on the railroad. Many Indians later became merchants and storeowners. During colonial times, they occupied a racial netherland: they were treated poorly by the British (although not as poorly as blacks), and resented by the Africans. Even after independence, this resentment continued and half of the Indian population left the country.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

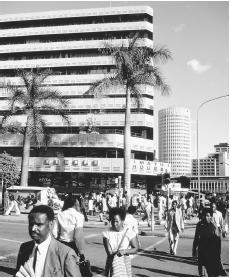

About 70 percent of the population is rural, although this percentage has been decreasing as more Kenyans migrate to the cities in search of work. Most of those who live in urban areas live in either Nairobi or Mombasa. Nairobi was founded at the beginning of the twentieth century as a stop on the East African Railway and its population is growing rapidly. Nairobi is a modern city with a diverse, international population and a busy, fast-paced lifestyle. The city is in close proximity to Nairobi National Park, a forty-four square mile preserve inhabited by wild animals such as giraffes and leopards. Around the perimeter of the city, shantytowns of makeshift houses have sprung up as the population has increased, and the shortage of adequate housing is a major problem in urban areas.

Mombasa is the second-largest city; located on the southern coast, it is the country's main port. Its history dates back to the first Arab settlers, and Mombasa is still home to a large Muslim population. Fort Jesus, located in the old part of the city, dates to the Portuguese settlement of the area in 1593, and today houses a museum. Kisumu, on Lake Victoria, is the third-largest city and is also an important port. Two smaller cities of importance are Nakuru in the Eastern Rift Valley and Eldoret in western Kenya.

In the cities, most people live in modern apartment buildings. In the countryside, typical housing styles vary from tribe to tribe. Zaramo houses are made of grass and rectangular in shape; rundi houses are beehive-like constructions of reed and bark; chagga houses are made from sticks; and nyamwezi are round huts with thatched roofs. Some rural people have adapted their houses to modern building materials, using bricks or cement blocks and corrugated iron or tin for roofs.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Corn (or maize) is the staple food of Kenyans. It is ground into flour and prepared as a porridge called posho, which is sometimes mixed with mashed beans, potatoes, and vegetables, to make a dish called irio. Another popular meal is a beef stew called ugali. This is eaten from a big pot, and each diner takes a piece of ugali, which he or she uses as a spoon to pick up beans and other vegetables. Boiled greens, called mboga, are a common side dish. Banana porridge, called matoke, is another common dish. Meat is expensive, and is rarely eaten. Herders depend on milk as their primary food, and fish is popular on the coast and around Lake Victoria. Mombasa is known for its Indian foods brought by the numerous immigrants from the subcontinent, including curries, samosas, and chapatti, a fried bread. Snacks include corn on the cob, mandazi (fried dough), potato chips, and peanuts.

Tea mixed with milk and sugar is a common drink. Palm wine is another popular libation, especially in Mombasa. Beer is ubiquitous, most of it produced locally by the Kenyan Breweries. One special type of brew, made with honey, is called uki.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. For special occasions, it is customary to kill and roast a goat. Other meats, including sheep and cow, are also served at celebrations. The special dish is called nyama choma, which translates as "burnt meat."

Basic Economy. Kenya's economy has suffered from inefficiency and government corruption. The tourist industry has also been harmed by political violence in the late 1990s. Seventy-five to 80 percent of the workforce is in agriculture. Most of these

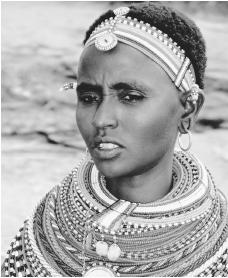

A young Samburu woman wearing traditional ornamentation.

workers are subsistence farmers, whose main crops are corn, millet, sweet potatoes, and such fruits as bananas, oranges, and mangoes. The main cash crops are tea and coffee, which are grown on large plantations. The international market for these products tends to fluctuate widely from year to year, contributing to Kenya's economic instability.

Many Kenyans work in what is called the jua kali sector, doing day labor in such fields as mechanics, small crafts, and construction. Others are employed in industry, services, and government, but the country has an extremely high unemployment rate, estimated at 50 percent.

Land Tenure and Property. During colonial rule, Kenyan farmers who worked the British plantations were forced to cultivate the least productive lands for their own subsistence. After independence, many of the large colonial land holdings were divided among Kenyans into small farms known as shambas. The government continues to control a large part of the economy, although in the late 1990s it began selling off many state farms to private owners and corporations.

Commercial Activities. The main goods produced for sale are agricultural products such as corn, sweet potatoes, bananas, and citrus fruit. These are sold in small local markets, as well as in larger markets in the cities, alongside other commercial goods and handicrafts. Bargaining is an expected, and at times lengthy, process in financial interactions.

Major Industries. The main industries are the small-scale production of consumer goods, such as plastic, furniture, and textiles; food processing; oil refining; and cement. Tourism is also important to Kenya's economy, due mainly to game reserves and resorts along the coast, but the industry has been hurt by recent political instability.

Trade. The primary imports are machinery and transportation equipment, petroleum products, iron, and steel. These come from the United Kingdom, the United Arab Emirates, the United States, Japan, and Germany. Kenya exports tea, coffee, horticultural products, and petroleum products to Uganda, the United Kingdom, Tanzania, Egypt, and Germany.

Division of Labor. Kikuyu are the best represented ethnic group in jobs of the highest status, followed by the Luo. Members of these two groups hold most of the highest positions in government, business, and education. Many Luo are fishermen and boat-builders; those who have moved to the cities often take up work as mechanics and craftsmen, and dominate Kenyan trade unions. A number of Maasai and Samburu have taken jobs as park rangers and safari guides. Along the coast, most merchants and storekeepers are of Indian or Arab descent. In farming communities, work is divided among people of all different ages; children begin helping at a very young age, and the elderly continue to work as long as they are physically able.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. There is a great deal of poverty in Kenya. Most of the wealthiest people are Kikuyu, followed by the Luo. Kenyans of higher economic and social class tend to have assimilated more Western culture than those of the lower classes.

Symbols of Social Stratification. Among herders such as the Masai, wealth is measured in the number of cattle one owns. Having many children is also a sign of wealth. In urban areas, most people dress in Western-style clothing. While western clothing does not necessarily indicate high status, expensive brand-name clothing does. Many women wear a colorful kanga, a large piece of cloth that can be wrapped around the body as a skirt or shawl and head scarves are also common. Some ethnic groups, such as the Kikuyu and the Luo, have adopted Western culture more readily than others, who prefer to retain their distinctive styles of dress and ornamentation. Women of the northern nomadic tribes, for example, wear gorfa, a sheepskin or goatskin dyed red or black and wrapped around the body, held in place with a leather cord and a rope belt.

Among some ethnic groups, such as the Rendille, a woman's hairstyle indicates her marital status and whether or not she has children. A man's stage of life is revealed by specific headdresses or jewelry. The Pokot and Maasai wear rows of beaded necklaces, as do the Turkana women, who wear so many strands that it elongates their necks. The above practices are indicators of marital and social standings within Kenyan society.

Political Life

Government. Kenya is divided into seven provinces and one area. The president is both chief of state and head of the government. He is chosen from among the members of the National Assembly, and is elected by popular vote for a five-year term. The president appoints both a vice-president and a cabinet. The legislature is the unicameral National Assembly, or Bunge. It consists of 222 members, twelve appointed by the president and the rest elected by popular vote.

Leadership and Political Officials. According to Kenya's constitution, multiple parties are allowed, but in fact it is President Moi's Kenya African National Union (KANU) that controls the government. The main opposition groups (which have little clout) are the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy-Kenya (FORD–Kenya), the National Development Party, the Social Democratic Party, and the Democratic Party.

Social Problems and Control. Crime (mostly petty crime) and drug use are rampant in the cities. Kenya has a common law system similar to that of Britain. There are also systems of tribal law and Islamic law, used to settle personal disputes within an ethnic group or between two Muslims. Citizens are not granted free legal aid except in capital cases, and as a result many poor Kenyans are jailed simply for lack of a legal defense. Kenya has a spotty record in the area of human rights, and does not allow independent monitoring of its prison system.

Nairobi, Kenya, is a thriving urban center.

Military Activity. Kenya's military includes an army, navy, air force, and the paramilitary General Service Unit of the Police, which has been used to put down civilian rebellions and protests. The country's military expenditures total 2 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP). Serving in the military is voluntary.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

Most social welfare is provided by the family rather than the government. There are government-run hospitals and health clinics, as well as adult literacy programs.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

There are a number of international organizations that work in Kenya to provide humanitarian aid and to help with the state of the economy and health care. These include the World Health Organization, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and others. There are also a number of human rights organizations, including the Kenya Antirape Organization, the Legal Advice Center, and the Catholic Justice and Peace Commission. Kenya is a member of the United Nations, the Commonwealth of Nations, and the Organization of African Unity.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. Among herders, men are responsible for the care of the animals. In agricultural communities, both men and women work in the fields but it is estimated that women do up to 80 percent of the work in rural areas: in addition to work in the fields, they take care of the children, cook, keep a vegetable garden, and fetch water and are also responsible for taking food to market to sell. It is common for men to leave their rural communities and move to the city in search of paying jobs. While this sometimes brings more income to the family, it also increases the women's workload. In urban areas women are more likely to take jobs outside the home; in fact, 40 percent of the urban work force is female. For the most part, women are still confined to lower-paying and lower status jobs such as food service or secretarial work, but the city of Kisumu has elected a woman mayor, and there are several women in Parliament.

The Relative Status of Men and Women. For the most part, women are treated as second-class citizens in Kenya. Despite the disproportionate amount of work that women do, men usually control the money and property in a family. Wife beating is common, and women have little legal recourse. Another women's issue is clitoridectomy, or female genital mutilation, which leaves many women in continual pain and vulnerable to infection. As women gain access to education, their status in society is increasing. Women's groups such as the National Women's Council of Kenya have been instrumental in pushing for just laws and in teaching women skills that allow them to earn a living.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Polygamy is traditional, and in the past it was not uncommon for men to have five or six wives. The practice is becoming less typical today as it has been opposed by Christian missionaries, and is increasingly impractical as few men can afford to support multiple partners. When a man chooses a potential wife, he negotiates a bride price of money or cattle with the woman's father. The price is generally higher for a first wife than for subsequent ones. The wedding ceremony and feast are celebrated in the husband's home.

Domestic Unit. In the traditional living arrangement, a man builds a separate hut for each of his wives, where she will live with her children, and a hut for himself. In a family with one wife, the parents often live together with girls and younger boys, while the older boys have smaller houses close by. It is common for several generations to live together under the same roof. According to tradition, it is the responsibility of the youngest son to care for his aging parents. Among the Maasai, houses are divided into four sections: one section for the women, one section for the children, one section for the husband, and one section for cooking and eating.

Inheritance. According to the tradition, inheritance passes from father to son. This is still the case today, and there are legal as well as cultural obstacles to women inheriting property.

Kin Groups. Extended families are considered a single unit; children are often equally close to cousins and siblings, and aunts and uncles are thought of as fathers and mothers. These large family groups often live together in small settlements. Among the Maasai, for example, ten or twelve huts are built in a circle surrounded by a thornbush fence. This is known as a kraal.

Socialization

Infant Care. Mothers usually tie their babies to their backs with a cloth sling. Girls begin caring for younger siblings at a very early age, and it is not uncommon to see a five- or six-year-old girl caring for a baby.

Child Rearing and Education. Child rearing is communal: responsibility for the children is shared among aunts, uncles, grandparents, and other members of the community. Boys and girls have fairly separate upbringings. Each is taught the duties and obligations specific to their sex: girls learn early how to carry water, cook, and care for children, while boys are schooled in the ways of herding or working in the fields. Children are also grouped into "age sets" with peers born in the same year. Members of a given age set form a special bond, and undergo initiation rituals as a group.

Primary school, which children attend from the age of seven to the age of fourteen, is free. Secondary school for students ages fourteen to eighteen is prohibitively expensive for most of the population. Only half of all children complete the first seven years of schooling, and only one-seventh of these

Farms in the Great Rift Valley of Kenya. In the 1990s, the government began selling state farms to private enterprises.

continue on to high school. After each of the two levels, there is a series of national exams which students must pass in order to continue in their studies.

Kenya's education system has been plagued with widespread accusations of cheating, and there is a shortage of qualified teachers to educate the burgeoning population of school-age children. In addition to government-run schools, churches and civic groups have established self-help or harambee schools, with the help of volunteers from the United States and Europe. These schools now outnumber government-run secondary schools.

Higher Education. There are eight universities in Kenya. The largest of these is the University of Nairobi, the Kenyatta University College is also located in the capital. In addition to universities, Kenya has several technical institutes which train students in agriculture, teaching, and other professions. Those who can afford it often send their children abroad for post-secondary education.

Etiquette

Kenyans are generally friendly and hospitable. Greetings are an important social interaction, and often include inquiries about health and family members. Visitors to a home are usually offered food or tea, and it is considered impolite to decline. Elderly people are treated with a great deal of respect and deference.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. The population is 38 percent Protestant and 28 percent Roman Catholic. Twenty-six percent are animist, 7 percent are Muslim, and 1 percent follow other religions. Many people incorporate traditional beliefs into their practice of Christianity, causing some tension between Kenyans and Christian churches, particularly on the issue of polygamy. Religious practices of different ethnic groups vary, but one common element is the belief in a spirit world inhabited by the souls of ancestors. The Kikuyu and several other groups worship the god Ngai, who is said to live on top of Mount Kenya.

Religious Practitioners. In traditional religions, diviners are believed to have the power to communicate with the spirit world, and they use their powers to cure people of diseases or evil spirits. Diviners are also called upon to help bring rain during times of drought. Sorcerers and witches are also believed to have supernatural powers, but unlike the diviners they use these powers to cause harm. It is the job of the diviners to counter their evil workings.

Rituals and Holy Places. Among the Masai, the beginning of the rainy season is observed with a celebration which lasts for several days and includes singing, dancing, eating, and praying for the health of their animals. For the ritual dances, the performers die their hair red, paint black stripes on their bodies, and don ostrich-feather headdresses. The Kikuyu mark the start of the planting season with their own festivities. Their ceremonial dances are often performed by warriors wearing leopard or zebra skin robes and carrying spears and shields. The dancers dye their bodies blue, and paint them in white patterns.

Initiation ceremonies are important rites of passage, and they vary from tribe to tribe. Boys and girls undergo separate rituals, after which they are considered of marriageable age. Kikuyu boys, for example, are initiated at the age of eighteen. Their ears are pierced, their heads shaved, and their faces marked with white earth. Pokot girls are initiated at twelve years old, in a ceremony that involves singing, dancing, and decorating their bodies with ocher, red clay, and animal fat.

Weddings are important occasions throughout the country, and are celebrated with up to eight days of music, dance, and special foods.

Death and the Afterlife. At death, Kenyans believe that one enters the spirit world, which has great influence in the world of the living. Many Kenyans believe in reincarnation, and children are thought to be the embodiment of the souls of a family's ancestors.

Medicine and Health Care

The health care system in Kenya is understaffed and poorly supplied. The government runs clinics throughout the country that focus primarily on preventive medicine. These clinics have had some success in reducing the rate of sleeping sickness and malaria through the use of vaccines, but the country is still plagued with high rates of gastroenteritis, dysentery, diarrhea, sexually transmitted diseases, and trachoma. Access to modern health care is rare, particularly in rural areas, and many people still depend on traditional cures including herbal medicines and healing rituals.

Kenya has one of the world's highest birth rates, and birth control programs have been largely ineffective. The life expectancy, while higher than in some other African nations, is still only fifty-four years. AIDS has been devastating to the country, and at least five hundred Kenyans die of the disease each day. President Moi has declared the AIDS epidemic a national disaster, but has nonetheless refused to encourage condom use.

Secular Celebrations

New Year's Day is celebrated on 1 January, and Labor Day, 1 May. Other holidays include Madaraka Day anniversary of self-rule, 1 June; Moi Day commemorating the president's installation in office, on 10 October; Independence Day also called Jamhuri Day, on 12 December; Kenyatta Day, celebrating Jomo Kenyatta as the national hero, on 20 October. Also called Harambee Day, this festival includes a large parade in the capital and celebrations throughout the country.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. The National Gallery in Nairobi has a special gallery and studio space set aside for emerging artists. The University of Nairobi also supports a national traveling theater company.

Literature. Kenya has a strong oral tradition. Many folktales concern animals or the intervention of the spirits in everyday life; others are war stories detailing soldiers' bravery. The stories are passed from generation to generation, often in the form of songs. Contemporary Kenyan literature draws extensively from this oral heritage, as well as from Western literary tradition. Ngugi wa Thiong'o, a Kikuyu, is Kenya's most prominent writer. His first novels, including Weep Not, Child (1964) and Petals of Blood (1977) were written in English. Though they were strong messages of social protest, it was not until he began to write exclusively in Swahili and Kikuyu that Ngugi became the victim of censorship. He was jailed for one year, and later exiled to England. Other contemporary Kenyan writers, such as Sam Kahiga, Meja Mwangi and Marjorie Oludhe Macgoye, are less explicitly political in their work.

Graphic Arts. Kenya is known for its sculpture and wood-carving, which often has religious significance. Figures of ancestors are believed to appease the inhabitants of the spirit world, as are the elaborately carved amulets that Kenyans wear around their necks. In addition to wood, sculptors also work in ivory and gold. Contemporary sculptors often blend traditional styles with more modern ones.

Only half of Kenyan children complete the first seven years of schooling.

Artists also create the colorful masks and headdresses that are worn during traditional dances, often fashioned to represent birds or other animals. Jewelry is another Kenyan art form, and includes elaborate silver and gold bracelets and various forms of colorful beadwork.

In some tribes, including the Kikuyu and the Luhya, women make pottery and elaborately decorated baskets.

Performance Arts. Dancing is an important part of Kenyan culture. Men and women usually dance separately. Men perform line dances, some of which involve competing to see who can jump the highest. Dance is often an element of religious ceremonies, such as marriage, child naming, and initiation. Costume is an important element of many traditional dances, as are props: dancers often don masks and carry shields, swords, and other objects.

The music of Kenya is polyrhythmic, incorporating several different beats simultaneously. The primary instruments are drums but lutes, woodwinds, and thumb pianos are also used. Singing often follows a call-and-response pattern, and singers chant rhythms that diverge from those played on the instruments. Kikuyu music is relatively simple; the main instrument is the gicandi, a rattle made from a gourd. Other groups, such as the Luhya, have more complex music and dance traditions, incorporating a variety of instruments.

In the cities, benga, a fusion of Western and Kenyan music, is popular. Benga was originated by the Luo in the 1950s, and incorporates two traditional instruments, the nyatiti, a small stringed instrument, and the orutu, a one-string fiddle, as well as the electric guitar. Taarab music, which is popular along the coast, shows both Arabic and Indian influence. It is sung by women, with drums, acoustic guitar, a small organ, and sometimes a string section accompanying the singers.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

Kenya has few facilities for the study of physical sciences. The National Museum in Nairobi has collections of historical and cultural artifacts and the museum at Fort Jesus in Mombasa is dedicated to archeology and history.

Much of what scientific activity there is in Kenya revolves around conservation. There are a number of National Parks where the animals are protected, and scientists come from around the world to study the nation's rich and diverse wildlife.

Bibliography

Aieko, Monica. Kenya: Water to Unburden Women, 1999.

Clough, Marshall S. Mau Mau Memoirs: History, Memory, and Politics, 1998.

Kyle, Keith. Politics of the Independent Kenya, 1999.

Maxon, Robert M. and Thomas P. Ofacansky. Historical Dictionary of Kenya, 2000.

McGeary, Johanna, et al. "Terror in Africa." Time South Pacific, 17 August 1999.

"Moi, Lord of the Empty Dance." The Economist, 15 May 1999.

Morton, Andrew. Moi: The Making of an African Statesman, 1998.

"No Pastures New." The Economist, 18 January 1997.

Oded, Arye. Islam and Politics in Kenya, 2000.

Ogot, B. A. and W. R. Oghieng', eds. Decolonization and Independence in Kenya 1940-93, 1995.

Oucho, John O. Urban Migrants and Rural Development in Kenya, 1996.

Patel, Preeti. "The Kenyan Election." Contemporary Review, 1 April 1998.

Robinson, Simon. "Free as the Wind Blows." Time, 28 February 2000.

——. "A Rough Kind of Justice." Time South Pacific, 10 May 1999.

Russell, Rosalind. "Kenya Calls AIDS National Disaster, Bars Condom News Alerts." Reuters NewMedia, 30 November 1999.

Sayer, Geoff. Kenya: Promised Land?, 1998.

"Serial Killer at Large." The Economist, 7 February 1998.

Simmons, Ann M. "'Inherited' Kenya Widows Fear Spread of AIDS." Los Angeles Times, 13 March 1998.

Srujana, K. Status of Women in Kenya: A Sociological Study, 1996.

Turner, Raymond M., et al. Kenya's Changing Landscape, 1998.

Vine, Jeremy. "View from Nairobi." New Statesman, 2 January 1999.

Watson, Mary Ann, ed. Modern Kenya: Social Issues and Perspectives, 2000.

Women and Land Rights in Kenya, 1998.