Culture of Kazakhstan

Culture Name

Kazakh, Kazakhstani, Republic of Kazakhstan (note the spelling of Kazakhstan can be found with or without an h ; currently it is officially spelled with an h )

Alternative Names

Kazak, Central Asian or Post-Soviet People

Orientation

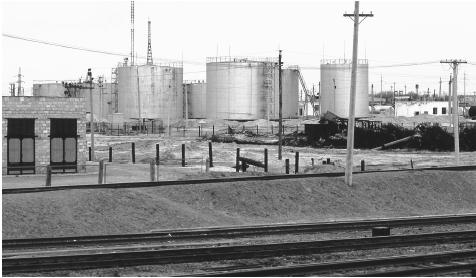

Identification. The Kazakh steppeland, north of the Tien Shan Mountains, south of Russian Siberia, west of the Caspian Sea, and east of China, has been inhabited since the Stone Age. It is a land rich in natural resources, with recent oil discoveries putting it among the world leaders in potential oil reserves. The newly independent Republic of Kazakhstan ranks ninth in the world in geographic size (roughly the size of Western Europe) and is the largest country in the world without an ocean port.

The Kazakhs, a Turkic people ethnically tied to the Uighur (We-goor) people of western China and similar in appearance to Mongolians, emerged in 1991 from over sixty years of life behind the Iron Curtain. Kazakhstan, which officially became a full Soviet socialist republic in 1936, was an important but often neglected place during Soviet times. It was to Kazakhstan that Joseph Stalin exiled thousands of prisoners to some of his most brutal gulags. It was also to Kazakhstan that he repatriated millions of people of all different ethnicities, in an effort to "collectivize" the Soviet Union. Kazakhstan was also the site of the Soviet nuclear test programs and Nikita Khrushchev's ill-conceived "Virgin Lands" program. These seventy years seem to have had a profound and long-lasting effect on these formerly nomadic people.

The process of shedding the Soviet Union and starting anew as the democratic Republic of Kazakhstan is made difficult by the fact that a large percentage of Kazakhstan is not Kazakh. Russians still make up 34.7 percent of the population, and other non-Kazakhs such as Ukrainians, Koreans, Turks, Chechnians, and Tatars, make up another 17 percent. Many of the non-Kazakh people of Kazakhstan have met attempts by the Kazakh government to make Kazakh the central, dominant culture of Kazakhstan with great disdain and quiet, nonviolent resistance. The picture is further complicated by the fact that many Kazakhs and non-Kazakhs are struggling (out of work and living below the poverty level). Democracy and independence have been hard sells to a people who grew accustomed to the comforts and security of Soviet life.

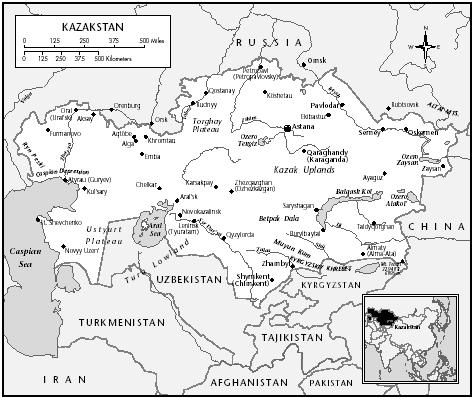

Location and Geography. Kazakhstan, approximately 1 million square miles (2,717,300 square kilometers) in size, is in Central Asia, along the historic Silk Road that connected Europe with China more than two thousand years ago. Five nations border current-day Kazakhstan: China to the east; Russia to the north; the Caspian Sea to the west; and Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan to the south. A pair of beautiful mountain ranges, the Altay and the Tien Shan, with peaks nearly as high as 22,966 feet (7,000 meters), runs along Kazakhstan's southeastern border. The area north and west of this is the vast Kazakh steppe. Life on the steppe is harsh, with extreme temperatures and intense winds. The lands leading up to the Caspian Sea in the west are below sea level and rich in oil. The historic Aral Sea is on Kazakhstan's southern border with Uzbekistan. In recent years the sea has severely decreased in size and even split into two smaller seas due to environmental mismanagement. The climate of Kazakhstan is extremely variable. The very south experiences hot summers, with temperatures routinely over 100 degrees Fahrenheit (38 degrees Celsius). The very north, which is technically southern Siberia, has extreme winters, with lows of well below 0 degrees Fahrenheit (-18 degrees Celsius), with strong winds, making the temperature feel like -50 to -60 degrees Fahrenheit

Kazakhstan

(-46 to -51 degrees Celsius). There are beautiful parts of Kazakhstan, with lakes and mountains that would rival many tourist destinations in the world. There are also parts of Kazakhstan that are flat and barren, making it seem at times like a forsaken place.

The capital of Kazakhstan was moved in 1996 to Astana, in the north-central part of the country far from any of Kazakhstan's borders. The former capital, Almaty, is still the largest city and most important financial and cultural center. It is located at the base of the Tien Shan Mountains in the far southeast near both China and Kyrgyzstan.

The move of the capital was very controversial among many in Kazakhstan. There are three main theories as to why the move was made. The first theory contends that the move was for geopolitical, strategic reasons. Since Almaty is near the borders with China and Kyrgyzstan (which is a friend but too close to the Islamic insurgent movements of Tajikistan and Afghanistan), this theory maintains that the new, central location provides the government with a capital city well separated from its neighbors. A second theory asserts that the capital was moved because Kazakh president Nursultan Nazarbayev wanted to create a beautiful new capital with new roads, buildings, and an airport. The final theory holds that the Kazakh government wanted to repatriate the north with Kazakhs. Moving the capital to the north would move jobs (mostly held by Kazakhs) and people there, changing the demographics and lessening the likelihood of the area revolting or of Russia trying to reclaim it.

Demography. The population of Kazakhstan was estimated to be 16,824,825 in July 1999. A census taken just after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 indicated a population of more than 17 million. The decreasing nature of Kazakhstan's population (-.09 percent in 1999) is due, in part, to low birth-rates and mass emigration by non-Kazakhs, mainly Russians and Germans (Kazakhstan's net migration rate was -7.73 migrants per 1,000 people in 1999). Given the emigration, Kazakhstan's ethnic make up is ever-changing. For 1999 the best estimates were Kazakhs 46 percent, Russians 34.7 percent, Ukrainians 4.9 percent, Germans 3.1 percent, Uzbeks 2.3 percent, Tartar 1.9 percent, and others 7.1 percent. Many observers predict that continued emigration by non-Kazakhs and encouraged higher birthrates of Kazakhs by the government will lead to Kazakhs increasing their numbers relative to other ethnicities in Kazakhstan.

Linguistic Affiliation. Language is one of the most contentious issues in Kazakhstan. While many countries have used a common language to unite disparate ethnic communities, Kazakhstan has not been able to do so. Kazakh, the official state language of Kazakhstan, is a Turkic language spoken by only 40 percent of the people. Russian, which is spoken by virtually everyone, is the official language and is the interethnic means of communications among Russians, Kazakhs, Koreans, and others.

The move to nationalize Kazakhstan through the use of Kazakh has presented two main problems. During Soviet times, when Russian was the only real language of importance, Kazakh failed to keep up with the changing vocabulary of the twentieth century. In addition, Russian is still very important in the region. Knowledge of Russian allows Kazakhstan to communicate with the fourteen other former Soviet republics as well as with many people in their own country.

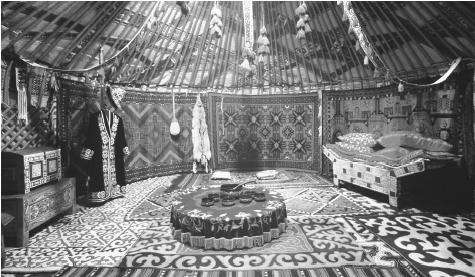

Symbolism. Kazakhs are historically a nomadic people, and thus many of their cultural symbols reflect nomadic life. The horse is probably the most central part of Kazakh culture. Kazakhs love horses, riding them for transportation in the villages, using them for farming, racing them for fun, and eating them for celebrations. Many Kazakhs own horses and keep pictures of them in their houses or offices. Also a product of their formally nomadic lives is the yurt, a Central Asian dwelling resembling a tepee, which was transportable and utilitarian on the harsh Central Asian steppe. These small white homes are still found in some parts of Kazakhstan, but for the most part they are used in celebrations and for murals and tourist crafts.

Also central to Kazakh symbolism are Muslim symbols. Kazakhs are Muslim by history, and even after seventy years of Soviet atheism, they incorporate Islamic symbols in their everyday life. The traditionally Muslim star and crescent can be widely seen, as can small Muslim caps and some traditionally Muslim robes and headscarves in the villages.

Kazakhs are also very proud of their mountains, rare animals such as snow leopards, eagles, and falcons (a large eagle appears on the Kazakh flag under a rising sun), and their national instrument, the dombra, a two-stringed instrument with a thin neck and potbelly base, resembling a guitar.

The symbols of Soviet Kazakhstan still exist and are important to some people. At its peak there was hardly a town that did not have a statue of Lenin; a street named after the revolution; or a large hammer, sickle, and Soviet red star on many of its houses and public buildings. Much like the attempt to assert the Kazakh language, the increased use of Kazakh symbols on money, in schools, on television, and in national holidays has been tempered by those who do not wish to part with the Soviet symbols of the past.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. Humans have inhabited the Central Asian steppe since the Stone Age. Dramatic seasonal variations coupled with movements, conflicts, and alliances of Turkic and Mongol tribes caused the people of Central Asia often to be on the move.

In the eighth century a confederation of Turkish tribes, the Qarluqs, established the first state in Kazakhstan in what is now eastern Kazakhstan. Islam was introduced to the area in the eighth and ninth centuries, when Arabs conquered what is now southern Kazakhstan. The Oghuz Turks controlled western Kazakhstan until the eleventh century.

The eleventh through the eighteenth centuries saw periodic control over Kazakhstan by Arabs, Turks, and Mongols. The people of Kazakhstan consider themselves great warriors and still honor many of the war heroes of this time period.

What might be called the modern-day history of Kazakhstan started in the eighteenth century, when the three main hordes (groups) of Kazakh nomads (who had begun to distinguish themselves linguistically and culturally from the Uzbeks, Kyrgyz, and Turkmen) started seeking Russian protection from Oryat raiders from the Xhinjian area of western China.

In 1854 the Russian garrison town of Verny (modern-day Almaty) was founded. It was not long before Russian incursions into Central Asia became much more frequent. By the end of the nineteenth century the Russians had a firm foothold in the area and were starting to exert their influence on the nomadic Kazakhs, setting the stage for the twentieth century transformation of the region by the Soviets.

The Soviet Union's interaction with Kazakhstan started just after the 1917 October Revolution, with Lenin granting the peoples of Central Asia the right to self-determination. This did not last long, and during the 1920s Moscow and the Red Army put down Muslim revolts throughout Central Asia after the Russian civil war. Centuries of nomadic tribal wars among Turks, Mongols, and Arabs were being replaced by a new kind of domination: the military might of the Red Army and the propagandistic Soviet machine of Stalin's Kremlin.

In 1924 Kazakhstan was given union republic status, and in 1936 full Soviet socialist republic status—a status that did not change until Kazakhstan was the last Soviet republic to break from Moscow and declare independence, on 16 December 1991.

The years between 1924 and 1991 were truly transformative for the people and land of Kazakhstan. Factories were built, schools reorganized, borders closed, and life changed in almost every facet. Soviet years were a time of immigration into Kazakhstan. Stalin's collectivization campaign after World War II brought people from the Caucasus, southern Russia, and the Baltic to Kazakhstan. Khrushchev's "Virgin Land" campaign in 1954 made much of Kazakhstan into farmland, run by huge collective farms, largely made up of the Russian and Ukrainian settlers brought in to run them.

Soviet wars were also very difficult for this region. World War II and the war in Afghanistan in the late 1970s killed many young Kazakh men and women. Kazakhstan was integral to the Soviet Union for its oil and minerals, fertile farmlands, tough warriorlike heritage, and its vast, wide-open lands suitable for nuclear testing.

In 1986 the Soviet Union and the world got a glimpse of how intact Kazakh nationalism remained. Riots broke out on 16 December in reaction to the Russian Gennady Kolbin being named head of the Kazakh Communist Party machine. Kazakhstan had been changed by the Soviet Union; its people looked and acted differently and its language had partially been neglected, but the Kazakh people were still proud of their history and their heritage.

In 1991, then Kazakh Communist Party leader Nursultan Nazarbayev declared independence for Kazakhstan. He had stayed faithful to Moscow the longest and supported Mikhail Gorbachev's efforts to keep the Union intact. The years since 1991 have seen many changes in Kazakhstan and its people. Democracy is attempting to take root in a land that hasn't known democracy at any time in its three thousand-year history. Nomadism, tribal warfare, Mongol dynasties, foreign domination, and Soviet communism have been all the Kazakh land has known.

National Identity. Several factors that are unique to Kazakhstan, its land, and its history, unite its people. Kazakhstanis are proud of the nation's abundant natural resources, agricultural potential, and natural beauty. They are also united in their shared history as a neglected republic during the Soviet years. While they toiled under Soviet rule, producing much of the agricultural and industrial product for the Soviet Union, the rest of the Union looked upon Kazakhstan as a barren place.

A very structured and uniform educational system exists in Kazakhstan. All ethnicities, whether urban or rural, study a similar curriculum. Thus, students throughout the country share the same education.

Ethnic Relations. According to many people of Kazakhstan, during the Soviet years they wanted for very little. Everyone had jobs, everyone had a house or an apartment, and food was abundant. The Kazakhs were part of a powerful union that challenged the United States and the other powers of the world. They lived in a socialist system that based its success on the hard work of its people. But to say that everything was equal and that there were no underlying tensions, especially between Russians and Kazakhs, would be untrue. Since the very days of Russian influence in Central Asia, many Kazakhs have met their presence with contempt and skepticism. This was furthered during the Soviet years when Russian language, Russian culture, and the power in Moscow took very prominent places in Kazakhstan. While tensions between the two groups were often subtle and barely visible, they erupted violently during the 16 December, 1986 riots over Russian control of the Kazakh Communist Party. The day of 16 December is a very important and proud one in recent Kazakh history, as evidence of their nationalism and unity as a people (in 1991, when independence was declared, 16 December was symbolically chosen as Independence Day).

Interior of a yurt, a mobile dwelling used by nomadic Kazakhs.

The latent tensions of 150 years of Russian influence in Kazakhstan, coupled with the increasingly more visible disapproval by Kazakhs of Russian domination, set the stage for the difficult first years of post-Soviet life. Kazakh nationalism has been unpopular with many non-Kazakhs, especially the Russians, and thousands have left as a result. Streets and schools have been renamed, statues of Lenin taken down, the national anthem and flag changed, old Soviet holidays forgotten, and new Kazakh holidays promoted. Ethnic tensions have been further strained by an economy and a political system that has produced extreme haves and have-nots. The guarantee of work, an apartment, free health care, and higher education that kept tensions low for seventy years have been replaced by unemployment, decaying health care, and expensive higher education.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

The yurt is the main architectural remnant from the Kazakh nomadic years. The yurt is a round, transportable dwelling not unlike the Native American tepee (the yurt being shorter and flatter than the tepee). The yurt was very useful to the nomadic Kazakhs, who needed a sturdy dwelling to protect them from the elements of the harsh plains, and its inhabitants would sit and sleep in them on thick mats on the floor. Very few Kazakhs live in yurts today, but sitting on the floor is still very common in many Kazakh homes, many preferring it to sitting in chairs or at a regular table. Yurts are widely used in national celebrations and in Kazakh arts and poetry as reminders of the Kazakhs' nomadic past.

Russian settlers in Kazakhstan also had an effect on Kazakhstani architecture. Small A-frame houses, Russian orthodox churches, and many new wooden buildings went up as Russians settled the area in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Very few of these building have survived the times besides some churches, which have been restored and protected.

The twentieth century and the Soviet Union brought many architectural changes to Kazakhstan. Hard work and unity were two central themes of the socialist years in Kazakhstan, and the architecture from this period is a large reflection of that. Most of the buildings built during this period were big and utilitarian. Hospitals, schools, post offices, banks, and government buildings went up from Moscow to Almaty in basically the same shape, size, and color. The materials used were usually just as rough, with concrete and brick being the most common.

Large Soviet apartment blocks went up in all of the cities across Kazakhstan. Arranged in small microdistricts, these buildings were usually five or six stories high and had three to four apartments of one, two, or three bedrooms each per floor.

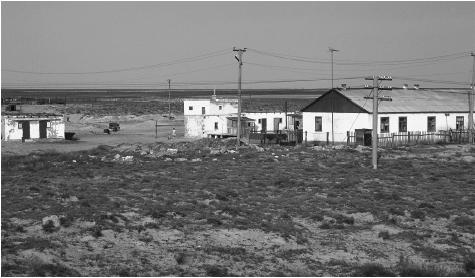

The villages and collective farms of Kazakhstan were of a different kind of Soviet architecture. Small two- to three-room, one-story houses, usually painted white and light blue (the light blue is thought to keep away evil spirits), adorn the countryside in Kazakhstan. The government built all houses, and there was no individualizing, excessive decorating, or architectural innovation. Very few, if any, houses were allowed to be more than one story high. A big house or an elaborate apartment was thought to be gaudy and very bourgeois.

While work and utilitarianism had definite effects on Kazakhstan's architecture, so did the belief in unity and the rights of the people. Public space was very important to the Soviets; in fact, nothing was privately owned, including one's home. Large collective farms were formed, transforming small villages into working communities, all with the same goal. Large squares and parks were built in almost every town and city. Everything belonged to the people, through the Communist apparatus in Moscow.

Times have certainly changed, as has the architecture in these post-Soviet days of independence. The old buildings, and the people who designed and built them, still exist. Some parts of Kazakhstan are in good repair and upkeep, while other parts look like an old amusement park that hasn't been used in years. In some cases cranes and forklifts stand in the exact places they were in when independence was declared and government money ran out. Rusted and covered in weeds and grass, much of the Soviet architecture and the people occupying it are in desperate need of help. This picture is further complicated and contrasted by the introduction of new buildings and new wealth by some people in Kazakhstan.

Oil money, foreign investments, and a new management style have created a whole new style in Kazakhstan. Almaty and Astana both have five-star high-rise hotels. The big cities have casinos, Turkish fast food restaurants, and American steak houses; modern bowling alleys and movie theaters are opening up amid old and decaying Soviet buildings. Private homes are also changing; sometimes next to or between old Soviet-style one-story austere houses, new two- and three-story houses with two-car garages and large, fenced-in yards are being built.

Food and Economy

Food in Kazakh culture is a very big part of their heritage, a way of respecting guests and of celebrating. When sitting down to eat with a Kazakh family one can be sure of two things: There will be more than enough food to eat, and there will be meat, possibly of different types.

Food in Daily Life. In daily life Kazakhs eat some of their own national dishes, but have borrowed some from the Russians, Ukrainians, Uzbeks, and Turks that they live among. Daily meals for Kazakhs usually are very hearty, always including bread and usually another starch such as noodles or potatoes and then a meat. One common dish is pilaf, which is often associated with the Uzbeks. It is a rice dish usually made with carrots, mutton, and a lot of oil. Soups, including Russian borscht, also are very common. Soups in Kazakhstan can be made of almost anything. Borscht is usually red (beet-based) or brown (meat-based), with cabbage, meat, sometimes potatoes, and usually a large dollop of sour cream. Pelimnin, a Russian dish that is made by filling small dough pockets with meat and onions, is very popular with all nationalities in Kazakhstan and is served quite often as a daily meal.

A more traditional Central Asian dish, although not conclusively Kazakh, is manti, a large dough pocket filled with meat, onions, and sometimes pumpkin.

Bread (commonly loaves or a flat, round bread called leipioskka ) and seasonal fruits and vegetables are served with almost every meal. Kazakhstan is known for its apples, and the Soviets are known for their love of potatoes (for both eating and making vodka).

Shashlik, marinated meat roasted over a small flame and served on a stick, is of great popularity in this region. The style of meat, which locals claim originated in the Caucasus is not often eaten on a daily basis at home but is eaten quite often at roadside cafés and corner shashlik stands. High quality shashlik in large quantities is served at home on special occasions or if an animal is slaughtered.

With their daily meals, Kazakhs drink fruit juices, milk, soft drinks, beer, water, and tea. Tea is an integral part of life in Kazakhstan. Many people sit down and drink tea at least six or seven times a day. Every guest is always offered tea, if not forced to stay and drink some. Tea is almost always consumed hot, as people in Kazakhstan think that drinking cold beverages will make one sick. Soft drinks, beer, and other drinks are drunk cold but never too cold, for fear of sickness.

Two children peruse movies advertisements in Alma Ata.

Tea drinking habits vary between Russians and Kazakhs. Russians drink their tea in teacups filled to the brim with hot tea. Kazakhs drink their tea in small wide-mouthed saucers called kasirs that they never fill more than halfway (usually only a quarter full). The intent is that the tea should never get cold, and the passing of the empty cup by a guest or a family member to the woman pouring tea serves as a way to keep them interacting, a way of showing respect. Kazakhs take tea drinking very seriously, and the ritualistic brewing, drinking, passing, and refilling of teacups take on a real rhythm and beauty when observed.

Kazakhs are both very traditional and superstitious and thus have a multitude of food and drink taboos. As Muslims, Kazakhs do not eat pork. This is a general rule, followed much more closely in the villages than in the more secular cities. Kazakhs also have great respect for bread. It should never be wasted or thrown away and should always be placed on the table right side up. Kazakhs will often forbid you to leave their house unless you have eaten at least some of their bread, even if it is just a small crumb.

A national habit is eating with one's hands. This is naturally more common in the villages, where traditions are more evident, but it is not uncommon to see Kazakhs in cities eat with their hands. In fact, the Kazakh national dish beshbarmak means "five fingers" in Kazakh.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Kazakhs have always held guests in high regard. Certain traditional Kazakh foods are usually served only on special occasions such as parties, holidays, weddings, and funerals. The most notable of these is beshbarmak, most traditionally made of horse meat. It is essentially boiled meat on the bone served over noodles and covered in a meat broth called souppa. The host, usually a man, takes the various pieces of meat and gives them out in an order of respect usually based on seniority or distance traveled. Each different piece of the horse (or goat, sheep or cow, never chicken or pig) symbolizes a different attribute such as wisdom, youth, or strength. Beshbarmak is always served in large quantities and usually piping hot.

When beshbarmak is made of sheep, the head of the sheep also will be boiled, fully intact, and served to the most honored guest. That guest then takes a bit of meat for himself or herself and distributes other parts of the head to other people at the table.

Another national food that is present at all celebrations is bausak, a deep-fried bread with nothing in the middle and usually in the shape of a triangle or a circle. The bread is eaten with the meal, not as dessert, and is usually strewn all over the traditional Kazakh table, which is called destrakan (the word refers more to a table full of traditional food than to an actual table). Bausak is strewn all over the table so that no part of the table is showing. Kazakhs like to have every inch of service area covered with food, sometimes with more food than will fit on the table, as a way of showing respect and prosperity.

A fermented horse's milk called kumis in Kazakh is also occasionally drunk at ceremonial occasions. This traditional milk dates back to the nomadic days, and many people in Central Asia think that the intoxicating beverage is therapeutic.

Vodka is consumed at all ceremonies. It is usually consumed in large quantities, and can be homemade or bought from a store (although usually only Russians make it at home). Toasts almost always precede a drink of vodka, and are given not only at special events but also at small, informal gatherings. Vodka permeates Kazakh and non-Kazakh culture and is central to all important meals and functions.

Basic Economy. Because of the richness of its land and resourcefulness of its people, the Kazakh basic economy is not very dependent on foreign trade and imports. The degree to which this is true varies greatly between the cities and towns, and the villages of the countryside. Almost every rural Kazakh has a garden, sheep and chickens, and some have horses. There are many meals in rural Kazakhstan where everything people eat and drink is homemade and from the person's garden or livestock. People in this region have been taught to be very resourceful and careful with what little they have. Most men can fix their own cars, houses, and farm equipment; women can cultivate, cook, sew, or mend almost everything they use in daily life. In fact, many rural dwellers make a living of growing foods or handmaking goods for sale in the local markets or in the cities.

For other goods, Kazakhs rely on a local market, where they buy clothes, electronics or other goods, mostly from Russia, Turkey, China, and South Korea. Urban Kazakhs rely much on grocery stores and now even big shopping malls in some cities for their goods and services.

Land Tenure and Property. Most people in Kazakhstan now own a house or an apartment for which they paid very little. Houses and property built and subsidized by the former Soviet government were very cheap and available to all during the Soviet years. With the collapse of the USSR most people retained the property that they had during Soviet years. New houses have been built and new property developed, and these are bought and sold in much the same way property is in any Western country. Most apartments are bought outright, but slowly the concept of developing an area and renting out the apartments and stores is becoming more popular. The area may face a real crisis as the houses and apartments that remain from the Soviet era need to be torn down or rebuilt, as people do not have much money for property or building supplies.

Commercial Activities. Seventy years of living in a land without imports or major foreign trade made the people of Kazakhstan rely heavily on their Soviet neighbors and on producing for themselves. In local markets, all types of goods and services are for sale, from produce to clothes, cars, and livestock. Kazakh carpets and handicrafts are probably some of the most famous exports from Kazakhstan. In addition, mineral and oil exports bring in much-needed revenue.

Major Industries. The major industries of Kazakhstan are oil, coal, ore, lead, zinc, gold, silver, metals, construction materials, and small motors. Kazakhstan produces 40 percent of the world's chrome ore, second only to South Africa. Besides the major fossil fuels and important minerals extraction, which is being supported by both foreign investment and the Kazakh government, much of the major industrial production in Kazakhstan has slowed or stopped. An industrial growth rate of -2.1 percent in 1998 was very frustrating to a country and people with such a rich land but with such a poor infrastructure and rate of capital investment.

Trade. Kazakhstan trades oil, ferrous and non-ferrous metals, chemicals, grains, wool, meat, and coal on the international market mostly with Russia, the United Kingdom, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, the Netherlands, China, Italy, and Germany. For the years between 1990-1997, 28 percent of working males were active in agriculture; 37 percent in industry; and 35 percent in services. During that same time period, 15 percent of working women were engaged in agriculture; 25 percent in industry; and 60 percent in services.

Division of Labor. Liberal arts colleges have only existed in Kazakhstan since independence in 1991. Until that time all institutes of higher education trained workers for a specific skill and to fill a specific role in the economy. This is still very much the case with high school seniors deciding among careers such as banking, engineering, computer science, or teaching.

A system of education, qualifications, work experience, and job performance is for the most part in place once a graduate enters the workforce. In recent years there have been widespread complaints of nepotism and other unfair hiring and promotion practices, often involving positions of importance. This has lead to cynicism and pessimism regarding fairness in the job market.

Social Stratification

Class and Castes. Some would argue that there is no bigger problem in Kazakhstan than rising social stratification at all levels. Kazakh capitalism has been a free-for-all, with a few people grabbing almost all of the power regardless of who suffers.

The terms "New Kazakh" or "New Russian" have been used to describe the nouveau riche in Kazakhstan, who often flaunt their wealth. This is in contrast to the vast number of unemployed or underpaid. A culture of haves and have-nots is dangerous for a country composed of many different ethnic groups used to having basic needs met regardless of who they were or where they came from. Poverty and accusations of unfair treatment have raised the stakes in tensions between Kazakhs and non-Kazakhs, whose interactions until recently have been peaceful.

Symbols of Social Stratification. The symbols of stratification in Kazakhstan are much like they are in many developing countries. The rich drive expensive cars, dress in fashionable clothes, and throw lavish parties. The poor drive old Soviet cars or take a bus, wear cheap clothes imported from China or Turkey, and save for months just to afford a birthday party or a wedding.

Political Life

Government. American legal and constitutional experts helped the Kazakhstani government write their constitution and form their government in1995. The system is a strong presidential one, with the president having the power to dissolve the parliament if his prime minister is rejected twice or if there is a vote of no confidence. The president also is the only person who can suggest constitutional amendments and make political appointments. There are some forms of checks and balances provided by a bicameral legislature called the Kenges. The Majlis, or lower house, has sixty-seven deputies

In villages, women are responsible for the domestic chores.

and the upper house, the Senate, has forty-seven senators. The powers of the legislature are severely limited; most glaringly, they don't even have the power to initiate legislation. The legal system is based on the civil law system. There is a Supreme Court of forty-four members and a Constitutional Court of seven members. While much of the control is centered in Astana with the president, legislature, and courts, there are fourteen provinces or states, called oblasts in Russian, with governors and certain rights.

Leadership and Political Officials. The president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, was the top Communist leader of the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic when the Soviet Union disbanded in 1991. After independence, Nazarbayev was easily elected president in November 1991. In March 1995 he dissolved parliament, saying that the 1994 parliamentary elections were invalid. A March 1995 referendum extended the president's term until 2000, solidifying Nazarbayev's control and raising serious doubts among Kazakhstani people and international observers as to the state of Kazakhstani democracy.

Multiparty, representative democracy has tried to take hold in Kazakhstan but has been met by opposition from Nazarbayev's government. The main opposition parties are the Communist Party, Agrarian Party, Civic Party, Republican People's Party, and the Orleu, or progress movement. A number of smaller parties have formed and disbanded over the years. The opposition parties have accused Nazarbayev and his Republican Party of limiting any real power of the opposition by putting obstacles and loopholes in their way, if not actually rigging the elections.

The most notable example of suppression of political opposition has been the case of Akezhan Kazhageldin, who was Nazarbayev's prime minister from 1994 to 1997. In 1999 Kazhageldin was banned from running in the 1999 presidential elections. He and his wife were charged with tax evasion (the conviction of a crime under the Kazakhstani constitution prevents a potential candidate from running for office) and arrested in September 1999 at the Moscow airport after arriving from London. Sharp criticism by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) over how the arrest was set up and carried out allowed Kazhageldin to return to London. The end result was that he was still not registered for the October election, and Nazarbayev won easily, with more than 80 percent of the vote. The OSCE and the United States criticized the election as unfair and poorly administered.

Social Problems and Control. In urban areas, robberies and theft are common. Murder, suicide, and other violent crimes are on the rise. The system for dealing with crime in Kazakhstan is based, in theory, on a rule of law and enforced by the police and the courts. Local and state police and local and national courts are set up much as they are in the United States and much of the rest of the Western world. The problem is the lack of checks and controls on this system. There are so many police and so many different units (remnants of the Soviet apparatus still exist, such as intelligence gatherers, visa and registration officers, and corruption and anitgovernmental affairs divisions, as well regular police and border controls) that it is often that jurisdiction is unclear. The strong sense of community, with neighbors looking out for each other, acts as a deterrent against crime. Civic education and responsible citizenry is emphasized in schools, and the schools work closely with local communities in this area.

The drug trade from Afghanistan and long, hard-to-patrol borders have given rise to organized crime, putting a strain on Kazakhstan's police and border patrol.

White-collar crime, such as embezzlement, tax fraud, and abuse of power and privilege are almost daily events, which seem to be tacitly accepted.

Military Activity. The military of the Soviet Union was very strong and well-trained. The armies of the post-Soviet republics are much weaker and less supported by the government. The available Kazakhstani military manpower of males between ages fifteen and forty-nine was estimated at 4.5 million in 1999, with about 3.5 million of those available being fit for service. All males over age eighteen must serve in the military for two years. Exemptions are made for those in school and the disabled. The 1998 fiscal year expenditures on the military were $232.4 million (U.S.)—1 percent of the GDP of Kazakhstan.

Kazakhstan is in a semiprecarious location. It has a friendly, although weakened, neighbor to the north in Russia. Recent complaints by Russians in Kazakhstan have begun to resonate in Moscow, putting some strain on relations that are for the most part friendly. Kazakhstan has a historical fear of China and thus watches its border with that country closely, but the most unstable areas for Kazakhstan involve its neighbors to the south. Movements in Afghanistan have spread to the failed state of Tajikistan, forming a center of Islamic fundamentalism not far to Kazakhstan's south. Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan have already dealt with attacks from rebel groups in Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan has significantly increased its military presence on its borders with Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. The region does not seem to be one that will readily go to war, while memories of the war in Afghanistan in the late 1970s are fresh in most people's minds.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

There is a government-sponsored program of pension and disability benefits. There is also support for single mothers with multiple children. The problem is that there is very little money for these programs. Pension levels have not kept up with inflation, and pensions are rarely paid on time, with those elderly, disabled, or unemployed often going months without payment.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

Kazakhstan and the rest of the former Soviet Union have seen a massive infusion of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and international aid programs. The passage of the Freedom Support Act by the United States' Congress has provided millions of dollars for direct U.S. governmental involvement in Kazakhstan and much-needed money for NGOs to operate there. The Peace Corps, United Nations Volunteers, and many other aid and educational organizations have been working hard in Kazakhstan. The groups are well received by the people and, for the most part, allowed to do their work by the Kazakhstani government.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. There is a large distinction between work and the home in Kazakhstani society. Women occupy very important roles in the Kazakhstani workforce. Women are, for example, school principals, bank presidents, teachers, accountants, police officers, secretaries, and government workers and make up almost half of the workforce. This may be a carryover from Soviet times when women were very important parts of a system that depended on every citizen to work and contribute.

Women are often the best students in a school and more qualified than men for many of the jobs in Kazakhstan. However, often women have not been promoted to the top positions in national government and the private sector. With alcoholism on the rise, especially among men, and educational performance among men often lower than average, women may play an even more significant role in the future Kazakhstani economy.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Kazakh culture is traditionally a patriarchal one, with much respect being given to men, especially elderly men. Symbols in the culture often represent power and warriorlike behavior, often associated with men. This can be seen in many Kazakh households. In villages and small towns women always prepare the food, pour the tea, and clean the dishes. Men will often lounge on large pillows or stand outside and smoke while women prepare food or clean up after a meal. Men do work around the house, but it is usually with the horses, garden, or car. There are many marriage and courtship customs that further assert the male as dominant in Kazakh society.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Marriage in Kazakhstan is similar to that in the United States and Europe. The reasons and even the process of marriage in Kazakhstan are also very similar. While years ago it was common for women to marry very young, times have changed; education has become much more important for both genders, and marriages for people in their mid-twenties are becoming more common. Marriages are not arranged by the parents but are usually formed through dating and courtship. Interracial marriage is rare but tolerated.

Three aspects of traditional Kazakh culture still occasionally affect marriage today in Kazakhstan. Marriage is forbidden to any couple related over the past seven generations. In addition, the male should be older than the female. Finally, the nomadic tradition of stealing a bride is still practiced, although rarely, by some Kazakhs.

Families of the bride and groom are usually heavily involved in the process of the wedding and subsequent marriage. The families meet before the wedding, and exchange gifts and dowries. Kazakh weddings are three-day events.

Divorce is not uncommon, especially in the urban centers. It is viewed in Kazakhstan as it is in other parts of the world—it is never ideal but some marriages were not meant to last. There are no formal rules for who gets what when a marriage ends, but women usually keep the children.

Domestic Unit. Households vary greatly in Kazakhstan. Some couples have only one or two children, while other families have eight or nine. Kazakhs tend to have more children than Russians. Men exercise most of the symbolic authority in both Kazakh and non-Kazakh households. But there are many very strong women and powerful matriarchs who wield all practical control.

Domestic units in Kazakhstan are very rarely just a mother, father, and their children. The practice of grandparents and extended family living

Oil refineries next to train tracks near Kul'Sary, Kazakhstan. Oil is one of the major industries in Kazakhstan.

within one household is very common. Kazakhs especially make very little distinctions among cousins, second cousins, aunts, uncles, and grandparents. Kazakhs also still largely adhere to an old custom of care for the elderly. The youngest son in Kazakh families is expected to stay at home until his parents die. He may take a wife and have a family of his own, but he is expected to care for his parents into their old age.

Kin Groups. Kin groups are central to the life of almost every Kazakh life. Who you are, who your family is, and where you are from are very important. Dating back hundreds of years to the times when the Kazakhs were divided into three distinct hordes or large tribes, it has been important to know about your kin groups. Extended families are large support networks, and relatives from far away can be expected to help financially in times of crisis.

Socialization

Infant Care. Childbirth in Kazakhstan occurs in a hospital under the care of a doctor whenever possible. Every district in the country has a hospital, and medical care is free; patients only pay for drugs and specialized tests and care. Mothers usually stay in the hospital with their infants for a few days after birth. Some Kazakhs practice a custom of not letting anyone besides close family members see a newborn for the first forty days of life; then the family holds a small party and presents the baby to extended family and friends. Babies are well cared for and cherished by all cultures in Kazakhstan. Independence and access to markets have brought improved access to infant care products.

Child Rearing and Education. Generally children go to kindergarten at ages four or five in Kazakhstan. First grade and formal schooling start at age six, when many Kazakhs have large parties celebrating the event.

Children in Kazakhstan are assigned to classes of about twenty-five students in the first grade; the class remains together through the eleventh grade. The class has the same teacher from the first through the fourth grade and then a different teacher from the fifth through the eleventh grade. These teachers become like second mothers or fathers to the students in that class, with discipline being an important factor. Homework is extensive and grades difficult, and students are very grade-conscious.

Kazakhstani schools stress the basics: literature, math, geography, history, grammar, and foreign languages. Workdays are held where students clean the school and the town. Classes on citizenship and army training are required. After school, arts and dance performances are very popular.

Higher Education. Many high school students—often as high as 75 percent—go on to attend some form of schooling after graduation. Liberal arts schools, many run by foreigners, are opening in the bigger cities. Technical schools and state universities are widespread and very popular. A tendency still exists to pigeonhole students by making them choose a profession before they enter school—a Soviet remnant that preached that every citizen had a specific role in society and the sooner he or she realized it and learned the trade the better. Unfortunately this practice is less flexible in the ever-changing Kazakhstani economy, leaving many young people underqualified for many of the emerging jobs.

Etiquette

Etiquette and cultural norms related to acceptable and unacceptable behavior vary between urban and rural Kazakhs. As a rule, rural Kazakhs tend to follow the cultural norms more strictly.

Kazakh men always shake hands with someone they know when they see each other for the first time in a day. Usually the younger man initiates this, and shows respect by extending both hands and shaking the older man's hand.

Both Kazakhs and non-Kazakhs remove their shoes when inside a house. Guests always remove their shoes at the door and often put on a pair of slippers provided by the host or hostess. Central Asian streets often can be very dusty or muddy, so wearing shoes indoors is a serious social offense.

Greetings are also very structured in Kazakhstan. In Kazakh culture, elder women and men are greeted with certain phrases showing respect. A Russian system of patronymics is still widely used.

Kazakhs can be superstitious, and whistling inside a house is unacceptable in almost all Kazakh homes. It is believed that whistling inside will make the owner of the house poor.

In general smoking by women is not accepted, especially in rural areas, and women who are seen walking and smoking at the same time are considered prostitutes.

Kazakhs, and many other people from the former Soviet Union, often don't smile at people in public except to those they know. Kazakhs rarely form lines when boarding crowded buses.

Many people in Kazakhstan treat foreigners with a visible degree of skepticism. With the work of the Peace Corps and many other international groups and companies, the image of a foreigner as a spy is starting to fade. Nevertheless Kazakhstani people will often stare at foreigners as they walk by.

Public affection between friends is very common. Women and girls often hold hands as they walk; boys wrestle and often hook arms or walk with their arms around each other. Kissing cheeks and embracing is perfectly acceptable between good friends.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Religion in Kazakhstan is in a time of change. Arabs brought Islam to the region in the ninth century, and more than a thousand years later, Russian Orthodoxy was introduced by Russian settlers from the north. For all intents and purposes no religion was practiced for the seventy years of Soviet influence over the region; religious participation was banned, and many churches and mosques were destroyed—religious traditions were lost in the name of Soviet atheism. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, 47 percent of the people profess to be Muslim (mainly Sunni branch) and 44 percent Russian Orthodox. However, few people practice religion in any formal way, but Kazakhs have incorporated religion into some parts of their everyday life; for example, they cover their faces in a short prayer when they pass graveyards where someone they know is buried, and they often say prayers after meals. Sayings such as "God willing" and "this is from God" are very common in everyday speech.

There are virtually no visible tensions between Muslims and Christians in Kazakhstan. Religion was such a nonfactor for so many years, and continues to occupy so little of everyday life, that it is simply not an issue of importance between Russians and Kazakhs.

Religious Practitioners. Most town mosques are cared for and staffed by a mullah, who conducts religious services at the mosque as well as funerals, weddings, and blessings. Russian Orthodox churches are in many parts of Kazakhstan, especially in the north and in large cities. Orthodox priests perform services and baptize children much as in the West.

Death and the Afterlife. Both Kazakhs and non-Kazakhs believe that the deceased go to a heaven after they die. Funerals and burials reflect this, as

A farm on the steppe grasslands near Kul'Sary, Kazakhstan. Many rural Kazakhs acquire the food they eat from their own land.

great care is taken in preparing bodies and coffins for burial. Funerals in this part of the world are very intense, with wailing being a sign of respect and love for the dead.

Funerals are usually held in the home of the deceased with people coming from afar to pay their respects. Russians and Kazakhs are usually buried in separate sections of the graveyard. If the means are available, a Kazakh can be buried in a mausoleum.

Medicine and Health Care

There are some hospitals in Kazakhstan where it is possible to get good health care, but many more are in poor repair, without heat or electricity, lacking basic drugs and medical supplies, and staffed by underqualified and severely underpaid doctors and nurses.

Doctors are still trained under the Soviet system of specialties, with very few general practitioners. Doctors also rely heavily on symptomatic diagnosis, as they do not have access to the latest machines and testing devices; often simple blood tests cannot be done. Nevertheless, doctors are trusted and respected.

People also rely heavily on home remedies such as hot teas, honey, vodka and Banya (a very hot version of a sauna used mainly for cleaning purposes, but also for sweating out diseases and impurities).

Secular Celebrations

Some of the principal secular celebrations are 8 March, Women's Day, a very important day in Kazakhstan and celebrated by all. Women are honored on this day and showered with flowers and entertained with skits and jokes by their male coworkers and family members. Narooz, Kazakh New Year—a holiday mainly celebrated by Kazakhs on 22 March, but also observed by Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, Turkmen, Iranians. It occurs on summer solstice. Kazakhs cook traditional foods, have horse races, and set up many yurts.

Victory Day on 9 May commemorates the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany. Day of the Republic, 25 October, was the day independence was declared. This day is a day of Kazakh nationalism, with many speeches, songs, and performances in Kazakh. Independence Day is celebrated on 16 December—this date was chosen to remember the riots in Almaty on 16 December 1986. The riots were the first display of Kazakh nationalism and solidarity. Independence day is celebrated much like the Day of the Republic.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. Under the Soviet Union, funding and support of the arts were available for those who enrolled in specialized schools for artists, dancers, and musicians. However today, government money for arts, besides what is provided through public schools and municipals houses of culture, has virtually dried up. Many artisans are supported through NGOs such as Aid to Artisans and the Talent Support Fund.

Literature. Students study both Kazakh and Russian literature. Great Russian and Kazakh writers such as Tolstoy, Pushkin, and Abai are well known in Kazakhstan. A high societal value is put on those who have read the famous works and can quote and discuss them.

Performance Arts. Despite funding cutbacks, plays, dance performances, art museums, and the upkeep of historical museums are very important to the people of Kazakhstan. There are beautiful theaters in the larger cities, and almost every town has a house of culture where plays, art classes, concerts, and dance performances can take place. Many cultures in Kazakhstan have a strong tradition of instrument playing, traditional dancing, and theatrical performances.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

The Soviet Union had, and its now independent republics have, some very well respected science universities in the world. Higher education is very specialized in Kazakhstan, with many universities or programs focusing on specialized fields of physics, technology, engineering, math, philosophy, and politics. Many famous academics have come from this part of the world, and education in these fields has remained important, although funding for them has slowed with the economic downturn in the region.

Bibliography

Abazov, Rafis. The Formation of Post-Soviet International Politics in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan, 1999.

Abraham, Kurt S. "A World of Oil—Kazakhstan, an Oasis in FSU Bureaucratic Quagmire; International Deals." World Oil, 220 (11): 29, 1999.

Agadjanian, Victor. "Post-Soviet Demographic Paradoxes: Ethnic Differences in Marriage and Fertility in Kazakhstan." Sociological Forum, 14 (3): 425, 1999.

Akiner, Shirin. Central Asia: A Survey of the Region and the Five Republics, 1999.

Arenov, M. M., and Kalmykov, S. K. "The Present Language Situation in Kazakhstan." Russian Social Science Review: A Journal of Translations, 38 (3): 56, 1997.

Asia and Pacific Review: World of Information, 6 September 2000.

Auty, R. M. The IMF Model and Resource-Abundant Transition Economies: Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, 1999.

Bhavna, Dave. "Politics of Language Revival: National Identity and State Building in Kazakhstan." Ph.D. Dissertation, Syracuse University, 1996.

Benko, Mihaly. Nomadic life in Central Asia, 1998.

Berler, Rouza. Cattle car to Kazakhstan: a Woman Doctor's Triumph of Courage in World War II, 1999.

Burkitbayev, S. "Rail transport in Kazakhstan." Rail International, 31 (3): 18, 2000.

Campbell, Craig E. Kazakhstan: United States Engagement for Eurasian Security, 1999.

Eizten, Hilda. "Scenarios of Statehood: Media and Public Holidays in Kazakhstan." Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, 1999.

Grant, Steven. Charms of Market, Private Sector Continue to Elude Three Central Asian Republics, 2000.

——. Order Trumps Liberty for Many in Three Central Asian Nations: Ethnic Differences Brewing?, 2000.

Hoffman, Lutz. Kazakhstan 1993–2000: Independent Advisors and the IMF, 2000.

Landau, Jacob M. Politics of Language in the ex-Soviet Muslim States: Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, 2000.

Luong, Pauline Jones and Weinthal, Erika. "The NGO Paradox: Democratic Goals and Non-democratic Outcomes in Kazakhstan." Europe-Asia Studies, (7): 1267–1294, 1999.

Mitrofanskaya, Yuliya, and Bideldinov, Daulet. "Modernizing Environmental Protection in Kazakhstan." Georgetown International Environmental Law Review, 12 (1): 177, 1999.

Pirseyedi, Bobi. The Small Arms Problems in Central Asia: Features and Implications, 2000.

Pohl, Michaela. "The Virgin Lands between Memory and Forgetting: People and the Transformation of the Soviet Union, 1954–1960. Ph.D. dissertation, Indiana University, 1999.

Privratsky, Bruce G. "Turkistan: Kazakh Religion and Collective Memory." Ph.D. dissertation, University of Tennessee, Knoxville. 1998.

Sabol, Steven. "'Awake Kazak!': Russian Colonization of Central Asia and the Genesis of Kazakh National Consciousness, 1868–1920." Ph.D. dissertation, Georgia State University, 1998.

Schatz, Edward. "The Politics of Multiple Identities: Lineage and Ethnicity in Kazakhstan." Europe-Asia studies, 52 (3): 489–506, 2000.

Smith, Dianne L. Opening Pandora's Box: Ethnicity and Central Asian Militaries, 1998.

Sullivan, Barry Lynn. "Kazakhstan: An Analysis of Nation-Building Policies." M.A. dissertation, University of Texas, El Paso, 1999.

Svanberg, Ingvar. Contemporary Kazakhs: Cultural and Social Perspectives, 1999.

Timoschenko, Valery, and Krolikova, Tatiana. "Oil Pipeline Imperils the Black Sea." Earth Island 12 (3): 23, 1997.

Vartkin, Dmitri. Kazakhstan: Development Trends and Security Implications, 1995.

Werner, Cynthia Ann. A Profile of Rural Life in Kazakhstan, 1994–1998: Comments and Suggestions for Further Research, 1999.