Culture of Belize

Culture Name

Belizean

Orientation

Identification. Previously called British Honduras, the country now known as Belize derives its name from one of two historical sources: Maya root words or the surname of the Scottish buccaneer Peter Wallace, who maintained a camp near present-day Belize City in the seventeenth century. Belizeans affectionately refer to their country as "the Jewel."

The formation of a consciousness of a national culture coincided with the growth of the nationalist movement in the 1950s toward independence. It was a phenomenon that occurred simultaneously among neighboring British West Indian colonies.

Ethnic and geographic identification coincides with the areas where ethnic groups settled. In the north and west there are the mestizos, people formed by the union of Spaniards and Maya. In the central part, there are the Creoles, formed by the intermarriage of the British and their African slaves. In the south, there are the Garifuna, also called Black Caribs, along the coast and the Maya farther inland.The building of the capital city, Belmopan, in the late 1960s was a crowning achievement of the nationalist movement, radically transforming the settlement pattern. The immediate reason was to rebuild after the massive destruction of the old capital, Belize City, by a hurricane in 1961; another reason was to attract the population into the hinterland to engage in agriculture, which the government was promoting to replace timber, the hallmark of the colonial economy. The government was attempting to build a national culture emerging from colonialism with a new settlement pattern and a new economy.

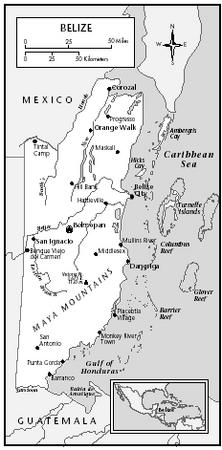

Location and Geography. Belize is at the southern end of the Yucatan peninsula, facing the Caribbean Sea. It covers 8,866 square miles (23,000 square kilometers) and has the second largest barrier reef in the world, which shelters scores of cays.

Demography. Immigration has been a major demographic factor. The latest massive inflow came from Latinos in the neighboring countries fleeing the civil unrest of the 1980s. Together with the long-resident Spanish-speaking group, they have become the largest ethnic group, according to the census of 1991. This group numbered 81,275, or 44 percent, of the national population of 189,392. The other main groups are the Creoles, 55,386 (30 percent); Maya, 20,447 (11 percent); and Garifuna, 12,343 (7 percent). While immigration has built the population, emigration has introduced a transnational fluidity between Belize and the United States. Since the 1960s thousands have left to settle in American cities, although many of those people retain family ties in Belize.

Linguistic Affiliation. The different groups speak their own languages, but the language spoken across ethnic lines is a form of pidgin English called Creole. There is much bilingualism and multilingualism. English is taught in all primary schools; however, its use is limited to official discourse and it appears more often in the written form than in the spoken.

Symbolism. The proponents of the nationalist movement introduced symbols as essential parts of the national culture they were crafting in the 1960s and 1970s. Prominent among them were the national bird, the toucan; tree, mahogany; and animal, tapir. In official discourse there was increasing use of the term "fatherland" to galvanize public sentiment away from a distant colonial power to a new nation state rooted in the cultural history of the Maya, the aboriginal settlers of the subregion.

Belize

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. The metamorphosis of Belize from a colony to a nation followed a set procedure postwar Britain had followed with dozens of other colonies: handing over the instruments of political power gradually to a democratically elected leadership. In Belize, the steps included introducing adult suffrage in 1954 and internal self-government in 1964, concluding an agreement with Guatemala to continue negotiations over its claims to Belizean territory, and gaining full independence on 21 September 1981.

National Identity. The development of a national identity became a task for the political party that won all the elections until 1984, becoming the voice of the nationalist movement and therefore earning the right to receive the instruments of statehood from Britain. Heading the party was an elite group whose members were Creole, urban-based, well educated, and mainly of lighter skin color.

Ethnic Relations. Transforming the nature of ethnic relations was a crucial task for the emerging political elite. The major change was from a British-imposed pecking order to a system in which all ethnic groups would have full access to the rights and privileges of citizenship. It was a deliberately inclusive approach that was popular and gave the impression of generating full public participation.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

At a distribution rate of eight persons per square kilometer, Belize has one of the lowest population densities in the hemisphere. The impact of underpopulation and the dispersed location of communities becomes clear when traveling through the countryside for miles and finding clusters of small villages nucleated around small towns. Traditionally, communities were built along waterways— both seacoast and riverbanks— to facilitate the transportation of timber logs for export. This basic pattern still remains for almost all the towns.

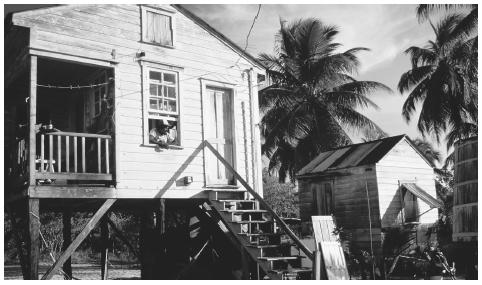

Another trait reflective of the earlier easy availability of timber is the predominance of wood as the basic material for housing. Hurricane devastation, however, has led to the greater use of ferro-concrete for building after 1960.

The architecture has also changed with the use of the main building material. Up to the middle of this century the design of houses was influenced by styles from the turn of the twentieth century found throughout the British West Indies.

At the private level the current small sizes of houses for the large numbers of occupants leads to relatively small space available for individuals. On the other hand, there has been too little allocation of space for public parks, where children and adults can spend recreation time. The country's landscape, therefore, consists of a series of small but congested communities, an irony for a country with abundant land.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Imported bleached wheat flour, corn, beans, rice, and poultry are the daily staples. There are hardly any food taboos, but there are beliefs across ethnic groups that certain foods, notably soups and drinks, help restore health.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Apart from specific preferences for some food items at large religious ceremonies, especially among the Garifuna, the items eaten at ceremonies are basically those eaten daily. At such ceremonies, there are usually store-bought alcoholic beverages. Only in some rural communities are home-fermented fruit wines drunk.

Basic Economy and Trade. The national currency is known as the Belizean dollar. In the 1990s, there were periods when the country was self-sufficient in corn, rice, beans, poultry, pork, and beef, marking the first time that demand for those staples was satisfied consistently. However, the third largest import is food, which in 1996 amounted to 17 percent of total imports.

Food production for export receives favorable treatment by the government, including lobbying for international markets. The result is that food items—mainly sugar, citrus, and banana— accounted for 86 percent of exports in 1996 and contributed almost 80 percent of foreign exchange earnings.

Land Tenure and Property. The most pervasive legacy of colonialism in the modern economy is the concentration of land in large holdings owned by foreigners who use the land for speculation. This monopoly resulted in only 15 percent of the land available for agriculture being used for that purpose in the early 1980s. The government has never had a comprehensive land redistribution policy.

Commercial Activities and Major Industries. The gross domestic product (GDP) index shows the services sector (including banks, restaurants, hotels and personal services) as the largest, totaling 57 percent of a total GDP of $718 million in 1996. Within this sector, trades, restaurants, and hotels made up 18 percent. The main industry in the private sector remains agriculture, with fishing and logging lagging far behind.

Division of Labor. The most significant characteristic of the division of labor is the extensive movement of people, including foreign laborers entering agricultural industries andservice workers moving from their communities to areas where jobs are

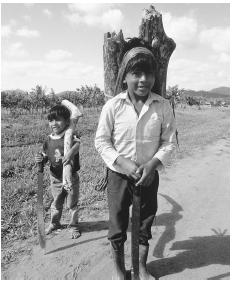

Two boys carry firewood in Maya Centre.

available. Agriculture supplies about 30 percent of all jobs. It consists of manual labor dominated by men from Honduras and Guatemala. Belizeans predominate in professional jobs and white-collar services. They commute daily from various parts of the country or stay during the week in Belmopan, Belize City, and the cays, where tertiary-sector jobs are available.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. While there is the traditional stratification into ethnic groups in the countryside, in urban communities there are conspicuous degrees of socioeconomic inequality in which skin color supersedes ethnicity. At the highest level, there are lighter-skinned Creoles, mestizos, and newly arrived North Americans, east Indians, and Middle Easterners. At the lower levels, there are darker-skinned Creoles and Garifuna. The highest levels retain control of the two political parties and the retail trade and other services in the tertiary sector. Those in the lower levels are largely unemployed.

The Maya and Garifuna demonstrate the surviving tribal traits of the aboriginal peoples. Both have the highest levels of poverty and participate least in the political and socioeconomic arenas. The Maya are subdivided into the Mopan and Ketchi peoples.

Political Life

Government. The government is a parliamentary democracy, and there is separation of the executive, legislature, and judiciary. However, the political parties have virtually eliminated the power of the legislature in favor of a cabinet of ministers.

Leadership and Political Officials. The Peoples United Party and the United Democratic Party provide the informal mechanisms that make the formal structures of the government function. Both draw support across all ethnic groups and social classes. All members of the government maintain openness to the public and encourage their constituents to communicate with them.

Social Problems and Control. The police force is the first line of intervention against crime. However, the police are active only in urban communities and the few villages with police stations. The judiciary is a survival from the British system, and appeals can still proceed as far as the Privy Council in London. Locally, the formal functioning of the system is jeopardized by a lack of judges, magistrates, and prosecutors, resulting in a backlog of cases.

The violent crimes that occur most frequently are murder and manslaughter, rape, and indecent assault. The most prevalent property crimes are larceny, theft, burglary, and robbery.

Military Activity. The national army provides protection against Guatemala, which in the past threatened to invade and implement its claim to Belizean territory. The army also is involved in drug interdiction efforts and assists in disaster preparedness and relief.

Social Welfare, Change Programs, and Nongovernmental Organizations

The government provides minimal amounts of money as relief for the indigent and for the public in times of disaster. Social change programs are targeted at groups such as youth, refugees, and the poor, usually in cooperation with multilateral agencies. The programs have been primarily ameliorative rather than focusing on skills and entrepreneurial training.

Several nongovernmental organizations are the intermediaries for international funding for these

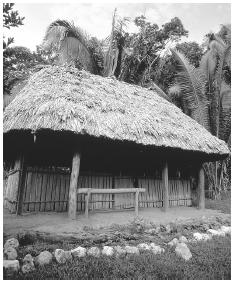

The exterior of a healer's hut, Panti Maya Medicinal Trail. Most people go to Mexico or Guatemala for Western medical treatment.

programs. Starting in the 1980s, the nongovernmental organizations have carried out many programs in raising social consciousness, research, environmental conservation, and economic development. With the steady dwindling of international support the nongovernmental organizations have declined in numbers. The few remaining are seriously attempting to finds alternative sources of support locally. They are increasingly factoring voluntarism within their support base. Such voluntarism had been the cornerstone of voluntary organizations that preceded the current crop of nongovernmental organizations in community self-help.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. Only a few women participate in the political, economic, social, and religious spheres; for example, among the twenty-nine elected members of the House of Representatives, there are only two women. A similar pattern exists in the religious ministries and the private sector.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Gender status tends to be more equitable at the levels of the household and the smaller community. Nominally there are more women-headed households among the Garifuna and Creole than among the Maya and mestizos. However, even among the Creole and Garifuna, deference is shown to male partners or relatives—whether they are co-resident or not—if they contribute financially and morally to the well-being of the household. In many rural communities, men and women function equally as shamans and healers.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Despite a tradition of openly accepted liaisons, there has always been a high social value placed on church-blessed unions. Among the Creoles and Garifuna, there may be prolonged common-law unions that are eventually recognized. Among the Maya, men and women start their conjugal lives before age 18 years life. Mestizos start a few years later and tend to remain in long-lasting unions. There are stringent requirements for divorce, but partners of broken marriages often live with others in common-law unions.

Domestic Unit and Kin Groups. Childbearing is not confined within the domestic unit among many Belizeans. The first child or two may be born without any agreement between the parents to form a domestic unit. This leads to high rates of illegitimacy in some ethnic groups. For example, between 1970 and 1980, illegitimacy among the Creole and Garifuna was 70 to 80 percent, whereas among mestizos it was around 40 percent.

The separation of childbearing from domesticity leads to a need for extended families, which are primarily cognate kin groups. Apart from child rearing, the functions performed by kin groups include labor exchange and providing general support in times of need.

Inheritance. Most Belizeans die intestate but abide by the spirit of the laws governing inheritance. Priority is given to legal spouses and children whether from a legal marriage or not. Similar legislation was being planned in 1999 for surviving common-law spouses.

Socialization

Child Rearing and Education. Child rearing and early education are areas where urban people expect government support. Traditional practice persist in rural communities, where child rearing is provided by the extended family.

By law, a child has to attend primary school up to age fourteen. Through rote memory, a child learns the three R's and develops an appreciation of the national culture as well as learning basic Christian beliefs. Only 40 percent of primary school leavers go on to secondary schools because of poor performance in the national school-leaving examination and for lack space and limited funds for uniforms, textbooks, and fees.

Higher Education. Less than 1 percent of the population qualifies for higher education. A national university that was started in 1987 offers a limited range of programs; it has a student population of less than five hundred. The country also subscribes to the University of the West Indies, where annually about fifty Belizeans start their studies.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Christianity is the main religion. Most of the people are Roman Catholics, Anglican, Methodists, Baptists, or Mennonites. There are some Moslems and Hindus.

Religious Practitioners. The power of churches comes from their spiritual strength as well as from the state. State law allows for the incorporation of churches, relieving them from paying taxes. Ministers are state-sanctioned marriage officers, and the state integrates them as copartners in managing the vast majority of primary schools.

Rituals and Holy Places. Belize City and Belmopan are important sites for religious denominations. The Anglican Saint John's Cathedral was consecrated in Belize City in 1826. Roman Catholics have cathedrals in Belize City and Belmopan.

Death and Afterlife. In the areas of death and the afterlife, the non-Christian belief systems of the ethnic groups are most noticeable. Most groups celebrate elaborate ceremonies on behalf of the deceased. All the ethnic groups believe that their ancestors can intervene to influence events daily life.

Medicine and Health Care

Because of the inadequacy of the health care system, Belizeans use the medical services in Guatemala and Mexico. Many also resort to traditional systems, which employ amulets, plants, baths, incantations, and ancestral rituals. While Western-trained health workers once ostracized practitioners of the traditional system, the government has advocated some collaboration in the case of birth attendants.

A house on stilts in Placencia. Hurricane damage has led to more use of ferro-concrete in post-1960s dwellings.

Secular Celebrations

Three secular holidays predate the nationalist movement. Baron Bliss Day on 9 March celebrates a British benefactor who established a trust fund for the country's welfare. Commonwealth Day on the fourth Monday in May celebrates participation the British Commonwealth of Nations. Saint George's Caye Day on 10 September commemorates the victory by settlers in the last military effort of Spain to retake Belize in 1798. Holidays introduced as a result of the nationalist movement and later independence are 1 May, 21 September, 12 October, and 19 November. International Labour Day occurs on 1 May, 21 September marks the day Belize acquired independence in 1981, 12 October is Pan American Day, and 19 November commemorates the arrival and settlement of the Garifuna people.

The Arts and Humanities

Artists support themselves primarily by selling their works at exhibitions and performing at concerts. The buyers include wealthy Belizeans who display art for their private pleasure. The National Arts Council promotes training and the display of various forms of art.

Literature, Graphic Arts, and Performance Arts. A small body of written literature is published locally. There is a potentially rich source of oral literature, but hardly any is preserved in writing. The best developed graphic arts are painting and sculpture. Sculpture builds on a rich tradition of the use of wood. Mainly self-taught persons whose work demonstrates folkloric dimensions engage in painting and sculpture. A similar localized mode prevails in the performance arts, except drama and dance. Regional and international plays are performed in schools and occasionally for the public. There is much public support for those events.

Punta rock music is a component of the national culture that was created in the early 1980s by the Garifuna. It has become popular along the Caribbean coast of Central America.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

Foreign scientists mainly from North America do almost all the scientific research in the country. Studies in the fields of Maya archaeology, natural history, and the physical environment are primary contributors to our understanding of the significance of Belize within the subregion. Plans for consolidation of the University College of Belize includes promoting research for its students and faculty.

Bibliography

Bolland, O. Nigel. New Nation in Central America , 1986.

——. Colonialism and Resistance in Belize: Essays in Historical Sociology , 1988.

Dobson, Narda. A History of Belize , 1973

Government of Belize. Belize Estimates of Revenue and Expenditure for Fiscal Year 1999/2000 as Passed by the House of Representatives on Friday, 20 March 1999 , 1999.

——. Abstract of Statistics, Belize 1998 , 1998.

Krohn, Hunter Lita, et al., eds. Readings in Belizean History, 2d ed. , 1987.

Palacio, I. Myrtle. Who and What in Belizean Elections 1954 to 1993 , 1993.

——. Redefining Ethnicity: The experiences of the Garifuna and Creole , 1995.

Palacio, Joseph O. Development in Belize 1960–1980 , 1996.

Phillips, Michael D., ed. Belize: Selected Proceedings from the Second Inter disciplinary Conference on Belize , 1996.

Shoman, Assad. "The Birth of the Nationalist Movement in Belize 1950–1954." Journal of Belizean Affairs 2: 3–40, 1973.

——. Party Politics in Belize 1950–1986 , 1987.

Stone, Michael Cutler. Caribbean Nation, Central American State: Ethnicity, Race, and National formation in Belize, 1798–1990 , 1994.

UNICEF. A Situation Analysis of Children in Belize 1997 , 1997.

Vernon, Dylan. International Migration and Development in Belize: An Overview of Determinants and Effects of Recent Movement , 1988.

Wilk, Richard, and Mac Chapin. Ethnic Minorities in Belize: Mopan, Kekchi, and Garifuna , 1990.