Culture of Belarus

Culture Name

Belarusian

Alternative Names

Republic of Belarus, Respublika Belarus; before 1991, the country was known as the Belorussian (also spelled Byelorussian) Soviet Socialist Republic. Sometimes called White Russia or alternatively White Ruthenia, especially in relation to the pre-1918 history of the region. Culture name also known as Belarussian.

Orientation

Identification. The name Belarus probably derives from the Middle Ages geographic designation of the area as "White Russia." Historians and linguists argue about its etymology, but it was possibly used as a folk name referring to northern territories. Some historic sources also mention Red and Black Rus in addition to White Rus. Such labeling probably predates the times when the Kievan Kingdom came into existence. Historic sources mention Belarus during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries as a geographic name; it later gained specific political meaning, including nation-state identification.Although Belarusians are the dominant ethnic group in the country, the culture includes people of various ethnicities such as Lithuanians, Poles, Ukrainians, Russians, Jews, and Tartars. The richness and blend of the culture reflects the complexity of ethnic interactions that have been taking place in this region for hundreds of years.

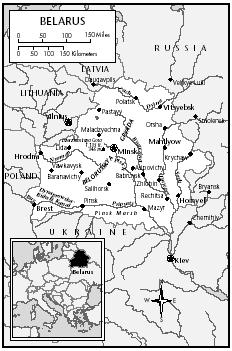

Location and Geography. Belarus is bounded by Poland and Lithuania on the west, Latvia in the northwest, Russia in the northeast and east, and Ukraine in the south. Belarus is a large plain about the size of Kansas, with a total area of 80,200 square miles (207,600 square kilometers).

The country is in the western portion of the East European Plains within the basins of the Dnepr, West Dvina, and Neman Rivers. The basins are connected, forming a system of natural waterways that link the Baltic and Black Seas. Much of the country is lowland with gently rolling hills; forests cover one-third of the land and their peat marshes are a valuable natural resource.

Modern Belarus is fairly evenly populated, with the exceptions of the marshes along the southern boundary with Ukraine. The capital, Minsk, is the largest and one of the oldest cities in the region and is centrally located.

Belarus has a moderate continental climate that is influenced by the Baltic Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. The summers are cool with some warm days, and winters are cold, while the average annual precipitation ranges 21.5 inches (546 mm) to 27.3 inches (693 mm). Average temperature ranges are from 63.5 degrees Fahrenheit (17.5 degrees Celsius) in July to 20 degrees Fahrenheit (-7 degrees Celsius) in January.

Demography. The population of Belarus was estimated to be 10,366,719 in 2000. The major ethnic groups in 2000 were Belarusians (77.9 percent), Russians (13.2 percent), Poles (4.16 percent), Ukrainians (2.9 percent), Jews (1.1 percent), Tartars, and Lithuanians (less than 1 percent). The demographic distribution remained consistent for centuries, but changed profoundly during the course of the twentieth century, especially due to the murder of Jews and Poles during the Holocaust and the influx of ethnic Russians.

The population density was estimated at 127 inhabitants per square mile in 2000. Women make up 53 percent of the population, and men the remaining 47 percent. Approximately 69 percent of the population is urban. The biggest city is Minsk, with around 1.7 million residents.

Belarus

Linguistic Affiliation. The official language is Belarusian, but Russian is also widely spoken. Furthermore, each ethnic minority—Polish, Ukrainian, and Lithuanian—also speaks its own language. Most Belarusians speak two or three languages, usually including Belarusian and Russian. About 98 percent of adult Belarusians are literate.

The Belarusian language belongs to the family of Slavic languages and is very close to Russian and Ukrainian. All the three languages use the Cyrillic alphabet, with minor modifications in Ukrainian and Belarusian. Until the early twentieth century, the Belarusian language stood out as a symbol of ethnic distinction. In the communist era, Russian became dominant. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, however, Belarusian is again being spoken and taught in schools as the national language.

"Lacinka" is the name of the Latin-script in Belarusian writing. It originated in the mid-sixteenth century as an aftermath of influence from Poland. Reformation, Counter-Reformation, and the expansion of the Western style of education were among the major factors leading to the considerable changes in the archaic Belarusian written language.

Symbolism. The state symbols of Belarus changed repeatedly throughout the twentieth century. In 1918 the Belarusian People's Republic took "The Pursuit" emblem (a horseman in motion, carrying a sword and shield) and the white–red–white flag as the state symbols. In 1919 the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic approved another state emblem: a hammer and sickle in the rays of the rising sun, surrounded by a garland of wheat. In 1956 the new Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR) approved a flag. It consisted of an upper red stripe and a lower green one. Additionally, there was a white Belarusian folk ornament on the red field. In 1991 the Republic of Belarus acquired the status of an independent sovereign state and "The Pursuit" emblem again became the state symbol and the white– red–white striped flag again became the state flag.

After the referendum in 1995, the state emblem of the Republic of Belarus was changed to an image of the republic's geographic outline in golden sunrays over the globe, with a five-pointed red star above. The image is framed by a garland of wheat, clover, and flax flowers. The golden inscription below reads "Republic of Belarus." The Belarusian national flag, which was accepted in 1995, looks like the 1956 design: two horizontal stripes (red and green) and a vertical element of white folk-design lace presented against the red background. The new state anthem has lyrics and music that reflect the everlasting aspiration of the Belarusian people for freedom and independence, and proclaims their commitment to ideals of humanism, goodness, and justice.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. Around the end of the ninth and the beginning of the tenth centuries, the Kievan Rus kingdom formed. Its two administrative provinces, the Polock and the Turov Principalities, covered the area of today's Belarus. For several centuries the Belarusian territories were strongly influenced by the Byzantine culture, including Orthodox Christianity, stone architecture, and literature. After the destruction of the Kievan Rus in the mid-thirteenth century by the Mongols the two Belarusian principalities were incorporated into the Great Lithuanian Duchy. A century later the Duchy formed a union with the Polish Kingdom. This new administrative and political situation brought a strong Western European influence to the region, including the Roman Catholic religion. A large Jewish population also settled in Belarus in the fourteenth century.

The Polish-Lithuanian Union created a strong political, economic, and military power in Eastern Europe. In 1569 the Great Lithuanian Duchy and the Polish Kingdom fused into a multiethnic federal state, one of the wealthiest and mightiest in Europe of the time, called the Commonwealth ( Rzeczpospolita ). The state enjoyed a powerful position in Europe for two centuries.

Following the partitions of the Commonwealth in 1772, 1793, and 1795 by Russia, Prussia, and Austria, respectively, the Belarusian territories became a part of the Russian empire. Great poverty under Russian rule, particularly among Jews, led to mass emigration to the United States in the nineteenth century. The second half of the nineteenth century witnessed the rapid development of capitalism in Belarus.

Beginning in the late 1880s, Marxist ideas proliferated in Belarus, and the 1905–1907 revolution produced the Belarusian national liberation movement. The nationalist newspaper Nasha Niva ("Our Land") was first published around this time. The most significant event in this national awakening process took place in April 1917, when the Congress of the Belarusian National Organizations took place. Its delegates claimed autonomy for Belarus. However, after the October Socialist Revolution in Petrograd succeeded, the Bolsheviks seized power in Belarus. In December 1917, they dissolved the all-Belarusian Congress in Minsk. Regardless of Soviet occupation, the all-Belarusian Congress and the representatives of the political parties declared the Belarusian People's Republic the first independent Belarusian state on 25 March 1918. Ten months later, the Bolsheviks proclaimed the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR). The new nation-state was formally incorporated into the Soviet Union (USSR), and remained part of that union until 1991.

On 27 July 1991, the Supreme Soviet of the BSSR adopted the Declaration on State Sovereignty. In August 1991, the Supreme Soviet of the BSSR suspended the Communist Party of Belarus and renamed the country the Republic of Belarus. In December 1991, the USSR dissolved and Belarus became a cofounder of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

In March 1994, Belarus adopted a new constitution, creating a presidency and reconstructing the 260-seat Parliament. On 10 July 1994, Alyaksandr Lukashenka was elected as the first President of Belarus. In 1997, the Treaty on the Union of Belarus and Russia was signed.

National Identity. National identity is symbolically linked to two significant moments in the Belarusian history. The national holiday is officially celebrated on 3 July, commemorating the day Soviet troops entered Minsk in 1944, liberating the city from Nazi forces. For some Bellarussians, 25 March is celebrated as an unofficial Independence Day. The date commemorates the short time period when Belarus broke free from the Bolshevik Russia in March 1918, only to be reoccupied in December 1918.

Ethnic Relations. Throughout the centuries, Belarusian lands were home to an ethnically and religiously diverse society. Muslims, Jews, Orthodox Christians, Roman and Greek Catholic Christians, and Protestants lived together without any major confrontations; Belarusians, Poles, Russians, Jews, Lithuanians, Ukrainians, and Roma (Gypsies) also lived in peace in Belarus. Although the twentieth century brought many challenges to this peaceful coexistence, Belarus is in many senses a culture of tolerance. The current population is primarily Belarusian but also includes Russians, Poles, Ukrainians, and Jews. All ethnic groups enjoy equal status, and there is no evidence of hate or ethnically-biased crimes.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

Belarus is predominantly rural with several large cities. Urban centers such as Minsk have been important in the development of Eastern European architecture since the eleventh century. Important religious monuments include the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Polotsk (begun in 1044), and churches such as Saint Euphrocine-Saviour Church in Polotsk, the Annunciation Church in Vitebsk, the Saint Boris and Gleb Church in Grodno (all built in the twelfth century). Many military fortifications and facilities were built between the thirteenth and the seventeenth centuries, in both Gothic and Renaissance styles. Many castles dating from the Middle Ages and Renaissance still stand, and in some cases the original wooden architecture has survived. Baroque churches were built in the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries, and at the end of the eighteenth century classicism began to dominate local architecture. Russian architects participated in town planning in the late nineteenth–early twentieth centuries, and towns were intensively

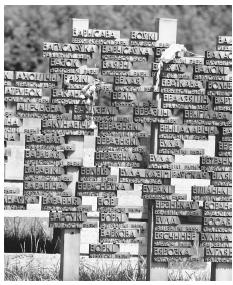

The Graveyard of Villages memorializes the 185 Belorussian towns destroyed by Nazi forces during World War II. The monument stands on the site of one of the towns, Khatyn, which burned to the ground in 1943.

built up. The architecture of twentieth century was characterized by both modernism and constructivism (such as the National Library of Belarus, built 1930–32).

Belarus is a farming country. Twenty-nine percent of the farm land is devoted to arable land; 15 percent to permanent pastures; 1 percent to permanent crops; 34 percent to forests and woodland; and 21 percent to other uses.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Belarusian eating habits are not very different from those of people in other Eastern European cultures. They usually have three main daily meals, and staples include red meat and potatoes. Belarusians are also very fond of spending their free time in the woods searching for the many types of mushrooms that are used in soups and other dishes.

Favorite Belarusian dishes include borscht ,a soup made with beets that is served hot with sour cream; filet àla Minsk and Minsk cutlet; potato dishes with mushrooms; and pickled berries. Mochanka is a thick soup mixed with lard accompanied by hot pancakes. There is also a large selection of international and Russian specialities available. A favorite drink is black tea, and coffee is generally available with meals and in cafés, although standards vary. Soft drinks, fruit juices, and mineral waters are widely available.

Ethnographic studies confirm that most Belarusians in the beginning of the twentieth century subsisted on a rather poor diet. No significant change can be noticed since the inception of the Soviet rules after the Bolshevik Revolution and the picture of a family eating from a common bowl has been changing slowly. After World War II, due to industrialization and economic changes, the eating habits have changed, but not profoundly.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Food customs often involve women and point out their role in society. For instance, setting a food table was customarily a woman's job. Men would not engage in such activity. An interesting food custom is related to matchmaking, which was always associated with drinking vodka and having food. First the matchmaker would visit a house of a potential bride and offer drinks and food. If the suitor was accepted, he would appear with the matchmaker at the woman's house with vodka and the woman's parents would provide food. Interestingly, the ceremony could be repeated several times until the couple would be officially engaged. If the engagement were broken, whoever broke the engagement would have to repay the other side for all expenses.

After a funeral, the mourners gather together for a meal.

Basic Economy. The official currency is the rouble (R) (also known as the zaichik ) divided into 100 kopecks. Belarus is an industrial state with developed and diversified agriculture. The main industries include electric power, timber, metallurgy, chemicals and petrochemicals, pulp and paper, building materials, medical, printing, machine-building, microbiology, textiles, and food industries.

The agricultural products are dairy and beef products, pork, poultry, potatoes, and flax. Agricultural production is highly industrialized and is based on the use of modern technology such as tractors, machine tools, trucks, equipment for animal husbandry and livestock feeding, and chemical fertilizers. Agricultural lands make up more than 46 percent of Belarus's territory, and agriculture accounts for about 20 percent of the national income. State-run farms are main producers of agrarian goods. Privately-owned farms are in the state of development.

A teacher instructs students during a physical education class at their school in Minsk. The state controls child rearing and education.

The nuclear accident at the Chernobyl (Ukraine) power plant in 1986 had a devastating effect on Belarusian agricultural industry. As a result of the radiation, agriculture in a large part of the country was destroyed, and many villages were abandoned.

Since gaining its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Belarus has moved relatively slowly on privatization and other market reforms, emphasizing instead close economic relations with Russia. About 80 percent of all industry remains in state hands, and foreign investment has been hindered by a political climate not always friendly towards business. Economic output, which had been declining for several years, revived somewhat in the late 1990s. Privatization of enterprises controlled by the central government virtually ceased in 1996, and the Belarusian economy was in crisis. The volume of production in all branches of industries has decreased. The Russian financial crisis that began in autumn 1998 severely affected Belarus's Soviet-style planned economy. Belarus is almost completely dependent on Russia, which buys 70 percent of its exports. Belarus has seen little structural reform since 1995, when President Lukashenka launched the country on the path of "market socialism." Belarus's trade deficit has grown steadily since then, from 8 percent of total trade turnover in 1995 to 14 percent in the first quarter of 1997, despite the government's efforts to promote exports and limit imports. Lukashenka also re-imposed administrative control over prices and the national currency's exchange rate, and expanded the state's right to intervene arbitrarily in the management of private enterprise. Given Belarus's limited fiscal reserve, continued growth in the trade deficit will increase vulnerability to economic crisis.

Land Tenure and Property. Prior to the partition of the Commonwealth by the end of the eighteenth century, all land belonged to the local gentry and petty noblemen (predominantly Polish or Polonized Belarusians). Before 1861, when peasants were freed, only small parcels of land were in the hands of Belarusian farmers. Peasants had to work three days a week or one hundred fifty six days a year for the noblemen. Some landlords preferred cash to labor. The landlords also hired peasants (those who did not own land) as paid labor. In the beginning of the twentieth century small stretches of land were owned by the state (about 5 percent), some land was communal (about 34 percent), and the majority was in private hands (60 percent). By 1917 the state, church, and gentry owned 9.3 percent while the individual farmers held 90.7 percent of all arable land. Farms were grouped in small hamlets rather than villages (two to ten households). With each generation the family lots got smaller. Some farmers rented additional land from the noblemen or wealthy farmers. After the Bolshevik Revolution of the 1917, all land belonged to the state and large state-owned collective farms. This situation persisted at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

Major Industries. The vast Belarusian forests support a large lumber industry, contributing about one-third of the gross national product (GNP). Among the most developed branches of industry are automobile and tractor building, agricultural machinery, production of machine tools and bearings, electronics, oil extraction and processing, production of synthetic fibers and mineral fertilizers, pharmaceuticals, production of construction materials, textiles, and food industries. Much of the national industry is focused on ready-made products for export.

Trade. The country's main trading partners are the other CIS states. Among the primary products traded are buckwheat, chalk, chloride, clay, limestone, peat, potassium, quartz sand, rye, sodium chloride, sugar beets, timber, tobacco, wheat, farm machinery, fertilizers, glass, machine tools, synthetic fibers, and textiles. In 1999 Belarus exported $6 billion (U.S.) worth of goods. Among the most significant export partners are Russia (66 percent of export), Ukraine, Poland, Germany, and Lithuania.

Belarus imports such commodities as oil, natural gas, coal, ferrous metal, lumber, chemicals chemical semi-products, cement, cotton, silk, cars, buses, household appliances, paper, grain, sugar, fish. In 1999 Belarus spent approximately $6.4 billion (U.S.) on goods imported primarily from Russia (54 percent), Ukraine, Germany, Poland, and Lithuania.

Political Life

Government. The Republic of Belarus is united democratic, legal state. It is divided into six administrative regions: five provinces ( voblastsi, singular - voblasts' ; the administrative center name follows in parentheses): Brestskaya (Brest), Homyel'skaya (Homyel'), Hrodzyenskaya (Hrodna), Mahilyowskaya (Mahilyow), and Vitsyebskaya (Vitsyebsk), and one municipality ( horad ), Minsk. The basic law is the Constitution of 1994 (with variations and additions), amended by a referendum in 1996. The chief of state, the President, is elected by the population for a five year term. The legislative body, the National Assembly, is composed of the House of Representatives (one-hundred-ten deputies, elected by the population) and Council of Republic (sixty-four members, fifty six elected by domestic councils of deputies, eight appointed by the president). Members of the National Assembly serve four-year terms. A Ministerial Council, headed by the prime minister, is appointed by the President with the consent of the House of Representatives. Local government is managed by local Councils with executive and administrative power. The supreme judicial organ is the Supreme Court, which interprets the constitution.

Leadership and Political Officials. Critics and opposition members denounce the increasingly oppressive political atmosphere and human rights violations in Belarus under the Soviet-style authoritarianism of President Alyaksandr Lukashenko. In 1999, the year President Lukashenko was to step down, he held what was internationally considered to be a rigged national referendum. The referendum changed the constitution and allowed Lukashenk to cancel the elections and remain president.

Military Activity. Belarus has a sizable army, with approximately 98,400 active duty personnel. Military branches include the army (51 percent of personnel) and the air force (27 percent). The remaining 22 percent is divided among the air defense force, interior ministry troops, and border guards. As a landlocked country, Belarus does not have a navy. Military service is mandatory for males over eighteen years of age. Belarusian military expenditure amounts to approximately $156 million (U.S., in 1998), which is 1.2 percent of the gross domestic product and 1.8 percent of the GNP.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

There are several nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in Belarus. One of them is The Belarus Project, which supports judges, lawyers, human rights advocates, and journalists in making their case before international audiences and intergovernmental bodies regarding President Lukashenka's violations of human rights and the rule of law in Belarus. Much effort goes toward bringing Belarusian civic leaders to the U.S. State Department and to the United Nations to tell their own stories of the situation in Belarus. This also gives them the opportunity to meet with their international colleagues and with human rights organizations and other NGOs that may be helpful to their cause at home.

Commuters climb on and off a city bus in Minsk, the largest city, with a population of almost two million.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. Modern Belarus is a part of the industrialized world. But certain cultural traits, which are observable today, might be traced back to the past. During the last fifty years some changes can be noticed in terms of traditional labor patterns. Today men and women do the same jobs and they might even be compensated equal wages. But ethnographic sources confirm a strong division of labor by gender existing in the beginning of the twentieth century and some of those patterns can still be recognized today. They relate to eating and childrearing patterns. One of them is the obligation of setting the dinner table, which is exclusively a woman's job. It is usually a mother or wife who is responsible for the arrangements. A man would not interfere with this obligation; it may even be considered degrading for a man to perform this task. Also, children under fourteen years old traditionally were under mothers' care and fathers would not interfere.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Gender roles in Belarus remain very traditional. Men are considered the more powerful gender and as breadwinners, while women are required to take care of the children and household. This traditional structure is slowly changing, and women are beginning to gain more recognition and power. The gay movement is also slowly entering the region, although with some opposition.

Men occupy all top positions in various spheres of the economy and politics. After some gains, a considerable decline in the professional and social status of women has been observed recently. Belarusian women are the least protected social group on the job market, and their unemployment rate is around 65 percent. Part of the gender inequality problem is that Belarusian women do not identify their rights and interests as specifically women's issues. Many Belarusians do not see social injustice in the low status of women, and so do not protest the situation.

The first appearance of feminist initiatives came in 1991, when the Belarusian Committee of Soviet Women was transformed into the Union of Women in Belarus. Other independent women's organizations followed, such as the League of Women in Belarus, the Committee of Soldiers' Mothers, and the Women's Christian-Democratic Movement. From 1993 to 1996, the Ministry of Justice of Belarus registered other organizations that, in addition to the protection of women's rights, were designed to achieve other goals like promotion of the development of culture, the revival of national traditions, and environmental protection. These groups have appeared within the structures of trade unions in order to resolve problems of both working and unemployed women.

In the late 1990s, a number of women's organizations were formed that were tightly linked with certain political structures. For example, the Belarusian feminist movement "For the Renaissance of the Fatherland" united women of social-democratic orientation, while the "League of Women-Electors" were mainly members of the United Civil Party; a women's organization was set up within the Liberal-Democratic Party, called Women's Liberal Association. In 2000, there were more than twenty women's organizations registered by the Ministry of Justice in Belarus.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Traditionally, marriage was a matter of mutual consent between the young, but the custom also required the consent of the families involved. Daughters enjoyed considerable freedom and had many opportunities to meet young men. Several times a year there were public gatherings in a larger village or town. The young couple had to live with the husband's family and often marriage was a compromise. Both the bride and the groom were expected to contribute something to the marriage and the farm, and most often it was just labor. The most sought qualities of a woman were for her to be a good field worker and housekeeper. Personal beauty and wealth were of secondary importance. Belarusians required high moral qualities from their spouses and virginity of the bride, and occasionally also the groom, was a prerequisite for marriage. The wedding was celebrated in both houses and expenses were shared. Divorce was also by mutual consent.

Domestic Unit. Until modern times households based on extended kinship relations ( zadruga – joint families) were popular. The traditional zadruga household includes the father and all his sons living on one piece of land. Each married son would have his own hut, but the land, animals, and equipment was owned by the entire family. The family also worked and ate together. Private ownership was limited to personal belonging. Such extended family may have included as many as fifty members united under the authority of one senior. Interestingly, the family's head was not always the natural father or grandfather and the extended family often included distant relatives or even strangers who may have been adopted as family members. Labor invested in the farm rather than blood relations regulated the kin membership. A stranger could have become a family member temporarily or for a lifetime and in some situation could have acquired a status of the head of the extended household.

Usually, the father would assume the position of the family's head and after his death any of his sons (usually the oldest), or his brother, or even a stranger, could take up his position in the family. There was no official title of the position, although several folk terms exist. The kinship also regulated profit sharing. If an adult member had been separated from the kin and had not contributed labor, he would not participate in profit sharing. A son who was absent and did not contribute to the welfare of the kin would not get the same share as other family members including those who were not blood related. Some remains of this kin structure persisted until the Soviet times.

The senior of the kin always directed the work of the men, while his wife took care of the women's activities. The father held the legal title to the property, but he was limited in the possibilities to sell or trade the family assets for as long as there were legal heirs. The custom was designed to protect the children and their rights to own property. When the property was sold, minors, after reaching the legal age, could have claimed the sold property as theirs. There are records that on several occasions courts ruled in their favor.

Inheritence. With certain exceptions for unmarried daughters, men and women were equal to family property. Whatever they brought in to the marriage remained theirs forever. Only the common investments were considered as family holdings. After the death of the spouse, the property went back to their legal heirs or was returned to the home of their origin. All money that a woman made from selling her garden products was her property and the family had no right over such assets. Also, a daughter's earnings outside a farm, although handed over to the family, were her private property. The wife was not responsible for her husband's debts, but the husband was for his wife's. Belarusian married women enjoyed relative equality in decision-making and economic share. But daughters had no share in the family estates, and brothers were under the obligation to marry off their sisters. When there were only daughters in the family, they inherited the whole estate, and the husband of the eldest one was under obligation to take care of the younger until they married.

Socialization

Child Rearing and Education. Child rearing and education are controlled by the state. Mothers can take paid maternity leaves and paid sick-days when their children are ill. Schooling is free and primary and secondary schooling is mandatory. The state runs affordable kindergartens. More than 10 percent of the population continue their education in several universities around the country. Literacy level is very high; 98 percent of the population age fifteen and over can read and write.

Higher Education. There were fifty-five higher educational institutions in Belarus at the end of the twentieth century, including thirteen private schools. The largest state institutions are the Belarusian University; the University of Informatics and Radio-electronics; the Economic, Technological, Agricultural Technological, and Pedagogical Universities; the Polytechnic Academy; the Academy of Arts; the Academy of Music; the Academy of Physical Training and Sports; the Academy of Agriculture; the Brest, Gomel, Grodno, Vitebsk, Mogilev, and Minsk Linguistic Universities; the Vitebsk Technological University; and medical institutes in Gomel, Grodno, Vitebsk, and Minsk. There were 292 scientific establishments in Belarus, employing 26,000 scientists. The main scientific center is the National Academy of Sciences.

Etiquette

"Sardechna zaprashayem!" is the traditional expression used when welcoming guests, who are usually presented with bread and salt. Shaking hands is the common form of greeting. Hospitality is part of the Belarusian tradition; people are welcoming and friendly; and gifts are given to friends and business associates.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Christianity is the dominant faith. Byzantine Christianity was introduced to Belarus with the rise of the Kievan kingdom in the tenth century. With the incorporation of the Belarusian territories into the Great Lithuanian Duchy and later into the Polish-dominated Commonwealth, Roman Catholicism and Protestantism flourished in Belarus. At the end of the sixteenth century, the struggle between the Russian Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches produced the Orthodox Uniate Church, governed by the Vatican. The Orthodox Church dominated following the Russian defeat of uprisings in 1863 and 1864.

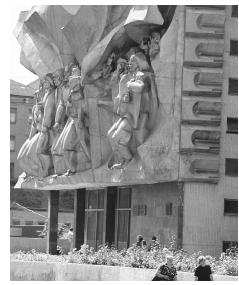

An imposing sculpture decorates the front of an apartment house in Minsk. Historical and domestic subjects were a common theme of early twentieth-century Belarusian art.

In 2000, Russian Orthodoxy claimed the most Belarusian believers (80 percent), followed by Roman Catholicism. The Christian community in Belarus is currently very diverse and includes several communities of Seventh-Day Adventists, Jehovah's Witnesses, Evangelists, Calvinists, and Lutherans, as well as Roman Catholics Orthodox practitioners, and Uniates. The most prevalent Protestant groups are Evangelic Christians and Christians of Evangelic Faith.

There are now about 44,000 Muslims, including people from the former Soviet republics and about 1,500 Arab students, in Belarus. The country has four mosques (in Ivye, Novogrudok [Navahradak], Slonim, and Smilovichi) and a fifth one at Vidzy in the Braslav district of the Vitebsk region will soon be designated.

Most of the Jews fled the region before World War II, were exterminated during that war, or emigrated after it ended. At the end of the eighteenth century, about 7 percent of Belarus's population was Jewish. At the beginning of the twentieth century, there were 704 synagogues; in 1995, only fifteen of them remained.

The number of Jews in Belarus can be estimated from the current number of members of the Union of Religious Jewish Congregations of the Republic of Belarus. This organization had at least 20,000 members in 2000 and has twelve regional offices. It effectively represents virtually the entire observant community and the Jewish community at large. It supplies humanitarian and medical aid and is affiliated with World Jewish Relief in the United Kingdom and B'nai B'rith in the States. The Main Synagogue of Minsk has daily morning and evening services.

Since the inception of Christianity into the region, the practitioners of Eastern Orthodoxy always outnumbered the followers of other religions. Regardless the times of religious freedom, there were also times of religious intolerance and persecutions. Religious rivalry between Catholicism and Orthodox Christianity amplified after 1839, when the Unite Church was abolished. All major political powers inflicted their policies against certain religions but the Poles and Soviets imposed the most drastic measures. Religious practices were seriously limited during the Soviet area or even outlawed. For instance, Jewish religion and culture, which has strong roots in Belarus, were discriminated under the Soviet rule. Most synagogues have been closed and the teaching of Hebrew and Judaism forbidden. Nevertheless, many Jews practiced their religious activities in secret. Since the Soviet era, the Eastern Orthodox Church in Belarus was a structural part of the Russian Orthodox Church. In February of 1992 the Belarusian Exarchate of the Moscow Patriarchate was created, but Moscow still heavily influences the Belarusian Church. Since 1989 the Vatican has been sending Catholic priests from Poland to work in Belarus.

Rituals and Holy Places. Among the most important religious holidays are Easter, Christmas, and days of remembrance. Russian Orthodox Easter is celebrated sometime between late March and early May, and the difference between Orthodox Easter and Catholic Easter may be up to six weeks. Roman Catholic Easter varies according to a lunar calendar. Russian Orthodox Christmas is celebrated on 5 January, and Roman Catholics celebrate on 25 December. Russian Orthodox practitioners observe Radaunitsa, a remembrance day, on 28 April, and Roman Catholics celebrate All Souls Day ( Dsiady ) on 2 November.

There are several places in Belarus that are related to various saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church, including Polock, Sluck, Brest, and Turov. The holiest place of the Russian Orthodox Church is the Garbarka Hill, in eastern Poland.

Medicine and Health Care

Hospital treatment and some other medical and dental treatment is normally provided without fee. Belarus has several large, diverse healthcare facilities, both hospitals and outpatient institutions. Specialized medicine is expanding and improving in the country, although students learn medicine in four medical institutes (in Minsk, Vitebsk, Grodno, Gomel), while eighteen medical schools prepare other medical personnel extensive epidemics of diphtheria have been reported in recent years.

Life expectancy at birth is 62 years for men and 74 years for women, with a population average of 68 years.

Secular Celebrations

Secular celebrations include the following national holidays: 1 January is New Year's Day; 8 March is International Women's Day, honoring the contribution of women to society; 1 May is Labor Day, celebrating the significance and the contribution of the working class and including a parade of citizens; Victory Day, celebrated 9 May, commemorates the victory over Nazi Germany in 1945. Independence Day is celebrated on 3 July and signifies the liberation of Minsk from the Nazi troops during WWII. The October Revolution Holiday, commemorating victory of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, is celebrated on 7 November.

The Arts and Humanities

Literature. The origins of Belarusian literature may be traced to the times of The Kievan Rus. Its formative period was during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and culminated in the sixteenth century when Francisk Skaryna, a publisher, humanist, scientist, and writer, published the first book—the Bible—in Belarusian.

Modern Belarusian literature originated in the nineteenth century, with a sense of national identity. V. Dunin-Marcinkevich, a poet and playwright, was the most dominant figure of the times. He developed literary forms new to Belarus (such as the idyll, ballad, and comedy), and significantly influenced the formation of the literature, dramatic art, and spiritual culture of Belarusians.

Belarusian literature flourished in the twentieth century; key figures were Yakub Kolas and Yanka

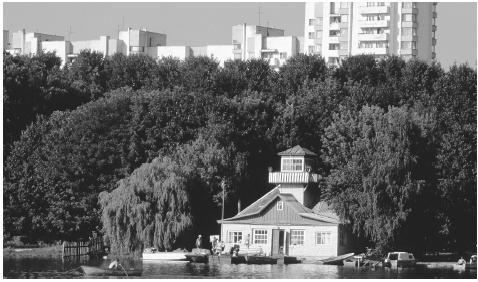

Swimmers and boaters congregate at a bathhouse on the shore of a lake, Minsk. The Baltic Sea and Atlantic Ocean influence the moderate climate.

Kupala, both poets, novelists, playwrights, critics, publicists, public figures, and founders of the modern Belarusian literature and language.

Graphic Arts. Painting first developed in Belarus in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, under influence of Byzantine art. Few works of that period remain, but fresco paintings like those in the Polotsk Sofia Cathedral have been preserved. In the sixteenth century, a fresco painting school was formed in Belarus. Works from the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries were stylistically connected with the painting of Poland and Western Europe; portraiture was popular.

"The Vitebsk School" played a major role in developing the Belarusian national art in the early twentieth century. The best internationally known member of the School was Marc Chagall, who was born near Vitebsk. He emigrated in 1922 and subsequently lived in France, Mexico, and the United States. Often his works depict scenes of his native Vitebsk, and Jewish life in a Belarusian town.

After the October Revolution of 1917, Socialist Realism became popular, with emphasis on historical and domestic subjects. Beginning in the 1940s, artists focused on battle scenes, particularly of the Great Patriotic War. In the 1980s and 1990s, Belarusian painting followed western trends and addressed intellectual and philosophical topics, relying on symbolic meanings and metaphors.

Since the 1980s, decorative and applied arts have been revived. Ceramics, glass, batik, and especially tapestry are popular. Folk art, like weaving from straw, is gaining prominence as well.

Performance Arts. Belarusian music shows strong folk and religious influences. During the nineteenth century the collection, publication, and study of Belarusian ethnic songs was begun. Folk influences still inspire many Belarusian composers, and there are many folk music festivals and competitions held annually. Many amateur ensembles of national song and dance, folklore groups, and ensembles of the folklore-scenic form take part in those cultural events.

Belarus has the National Academic Opera and Ballet Theater, as well as the State Musical Comedy Theater and State Symphonic Concert Orchestra. Belarusian opera and ballet are well known and admired internationally. Performing arts centers are found in big cities like Minsk, which has a thriving cultural scene with opera, ballet, theaters, puppet theater, and a circus. Brest also has a renowned puppet theater. Rock music in the Belarusian language first developed in the 1990s.

The Belarusian theater originated from folk traditions from various religious and secular holidays, and from family and domestic rites. One of the longest lasting traditions is puppet theater; it has played a major role in shaping national theatrical traditions. During the eighteenth century, several aristocratic families sponsored their own theaters, and in the twentieth century many new theaters emerged. Today the most famous are the State Theater of Musical Comedy, the Gorkiy State Theater, and the Theater-studio of the Film Actor in Minsk.

Belarusian cinematography tends to focus on heroic and romantic genres, as well as the psychology of characters. Belarusian directors are particularly known for their animated films. There is also an all female film studio in Belarus, Tatyana.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

All scientific activity is state-funded and organized through academic institutions, universities, or the institutes of the National Academy of Sciences. Belarus has a well-developed scientific community: the National Academy of Sciences, the Belarusian State University, and scientific and research institutes conduct investigations in the fields of quantum electronics, solid-state physics, genetics, chemistry, powder metallurgy, and other research fields.

Traditionally, academic emphasis has been on historical disciplines like archaeology, ethnology, ethnography, history, and art history, but the social sciences like sociology, psychology, and political science are gaining popularity.

Bibliography

Belarus (Now and Then), 1993.

Dawisha, Karen. Democratic Changes and Authoritarian Reactions in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova, 1997.

Ethnography of Belarus, 1989.

Garnett, Sherman W., ed. Belarus at the Crossroad, 2000.

Kelly, Robert C., ed. Belarus, Country Review 1999/2000, 2000.

Levy, Patricia. Belarus, 1998.

Marples, David. Belarus: From Soviet Rule to the Nuclear Catastrophe, 1996.

——. Belarus: Denationalized Nation, 1999.

Novik, Uladzimir. Belarus: A new country in Eastern Europe, 1994.

Vakar, Nicholas P. Belorussia. The Making of a Nation, 1956.

Zaprudnik, Jan. Belarus: At a Crossroads in History, 1993.