Culture of Bangladesh

Culture Name

Bangladeshi

Alternative Names

Bengali

Orientation

Identification. "Bangladesh" is a combination of the Bengali words, Bangla and Desh, meaning the country or land where the Bangla language is spoken. The country formerly was known as East Pakistan.

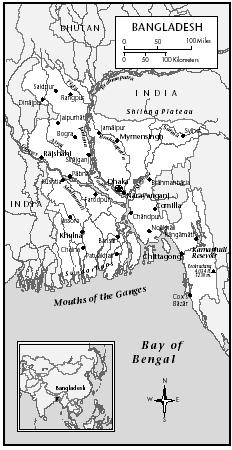

Location and Geography. Bangladesh straddles the Bay of Bengal in south Asia. To the west and north it is bounded by India; to the southeast, it borders Myanmar. The topography is predominantly a low-lying floodplain. About half the total area is actively deltaic and is prone to flooding in the monsoon season from May through September. The Ganges/Padma River flows into the country from the northwest, while the Brahmaputra/ Jamuna enters from the north. The capital city, Dhaka, is near the point where those river systems meet. The land is suitable for rice cultivation.

In the north and the southeast the land is more hilly and dry, and tea is grown. The Chittagong Hill Tracts have extensive hardwood forests. The vast river delta area is home to the dominant plains culture. The hilly areas of the northeast and southeast are occupied by much smaller tribal groups, many of which have strongly resisted domination by the national government and the population pressure from Bangladeshis who move into and attempt to settle in their traditional areas. In 1998 an accord was reached between the armed tribal group Shanti Bahini and the government.

Demography. Bangladesh is the most densely populated nonisland nation in the world. With approximately 125 million inhabitants living in an area of 55,813 square miles, there are about 2,240 persons per square mile. The majority of the population (98 percent) is Bengali, with 2 percent belonging to tribal or other non-Bengali groups. Approximately 83 percent of the population is Muslim, 16 percent is Hindu, and 1 percent is Buddhist, Christian, or other. Annual population growth rate is at about 2 percent.

Infant mortality is approximately seventy-five per one thousand live births. Life expectancy for both men and women is fifty-eight years, yet the sex ratios for cohorts above sixty years of age are skewed toward males. Girls between one and four years of age are almost twice as likely as boys to die.

In the early 1980s the annual rate of population increase was above 2.5 percent, but in the late 1990s it decreased to 1.9 percent. The success of population control may be due to the demographic transition (decreasing birth and death rates), decreasing farm sizes, increasing urbanization, and national campaigns to control fertility (funded largely by other nations).

Linguistic Affiliation. The primary language is Bangla, called Bengali by most nonnatives, an Indo-European language spoken not just by Bangladeshis, but also by people who are culturally Bengali. This includes about 300 million people from Bangladesh, West Bengal, and Bihar, as well as Bengali speakers in other Indian states. The language dates from well before the birth of Christ. Bangla varies by region, and people may not understand the language of a person from another district. However, differences in dialect consist primarily of slight differences in accent or pronunciation and minor grammatical usages.

Language differences mirror social and religious divisions. Bangla is divided into two fairly distinct forms: sadhu basha, learned or formal language, and cholit basha, common language. Sadhu basha is the language of the literate tradition, formal essays

Bangladesh

and poetry, and the well educated. Cholit basha is the spoken vernacular, the language of the great majority of Bengalis. Cholit basha is the medium by which the great majority of people communicate in a country in which 50 percent of men and 26 percent of women are literate. There are also small usage variations between Muslims and Hindus, along with minor vocabulary differences.

Symbolism. The most important symbol of national identity is the Bangla language. The flag is a dark green rectangle with a red circle just left of center. Green symbolizes the trees and fields of the countryside; red represents the rising sun and the blood spilled in the 1971 war for liberation. The national anthem was taken from a poem by Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore and links a love of the natural realm and land with the national identity.

Since independence in 1971, the national identity has evolved. Islamic religious identity has become an increasingly important element in the national dialogue. Many Islamic holy days are nationally celebrated, and Islam pervades public space and the media.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. The creation of the independent nation represents the triumph of ethnic and cultural politics. The region that is now Bangladesh has been part of a number of important political entities, including Indian empires, Buddhist kingdoms, the Moghul empire, the British empire and the Pakistani nation.

Until 1947 Bangladesh was known as East Bengal province and had been part of Great Britain's India holding since the 1700s. In 1947, Britain, in conjunction with India's leading indigenous political organizations, partitioned the Indian colony into India and Pakistan. The province of East Bengal was made part of Pakistan and was referred to as East Pakistan. West Pakistan was carved from the northwest provinces of the British Indian empire. This division of territory represented an attempt to create a Muslim nation on Hindu India's peripheries. However, the west and east wings of Pakistan were separated by more than 1,000 miles of India, creating cultural discontinuity between the two wings. The ethnic groups of Pakistan and the Indian Muslims who left India after partition were greatly different in language and way of life from the former East Bengalis: West Pakistan was more oriented toward the Middle East and Arab Islamic influence than was East Pakistan, which contained Hindu, Buddhist, Islamic, and British cultural influences.

From the beginning of Pakistan's creation, the Bengali population in the east was more numerous than the Pakistani population in the western wing, yet West Pakistan became the seat of government and controlled nearly all national resources. West Pakistanis generally viewed Bengalis as inferior, weak, and less Islamic. From 1947 to 1970, West Pakistan reluctantly gave in to Bengali calls for power within the government, armed forces, and civil service, but increasing social unrest in the east led to a perception among government officials that the people of Bengal were unruly and untrust worthy "Hinduized" citizens. Successive Pakistani regimes, increasingly concerned with consolidating their power over the entire country, often criticized the Hindu minority in Bengal. This was evident in Prime Minister Nazimuddin's attempt in 1952 to make Urdu, the predominant language of West Pakistan, the state language. The effect in the east was to energize opposition movements, radicalize students at Dhaka University, and give new meaning to a Bengali identity that stressed the cultural unity of the east instead of a pan-Islamic brotherhood.

Through the 1960s, the Bengali public welcomed a message that stressed the uniqueness of Bengali culture, and this formed the basis for calls for self-determination or autonomy. In the late 1960s, the Pakistani government attempted to fore-stall scheduled elections. The elections were held on 7 December 1970, and Pakistanis voted directly for members of the National Assembly.

The Awami League, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, was largely a Bengali party which called for autonomy for the east. Sheikh Mujib wanted to reconfigure Pakistan as a confederation of two equal partners. His party won one of 162 seats in the East Pakistan provincial assembly and 160 of the three hundred seats in the National Assembly. The Awami League would control national politics and have the ability to name the prime minister. President Yahya, however, postponed the convening of the National Assembly to prevent a Bengali power grab. In response, Sheikh Mujib and the Awami League led civil disobedience in East Pakistan. West Pakistan began to move more troops into the east, and on 25 March 1971, the Pakistani army carried out a systematic execution of several hundred people, arrested Mujib, and transported him to the west. On 26 March the Awami League declared East Pakistan an independent nation, and by April the Bengalis were in open conflict with the Pakistani military.

In a 10-month war of liberation, Bangladeshi units called Mukhti Bahini (freedom fighters), largely trained and armed by Indian forces, battled Pakistani troops throughout the country in guerrilla skirmishes. The Pakistanis systematically sought out political opponents and executed Hindu men on sight. Close to 10 million people fled Bangladesh for West Bengal, in India. In early December 1971, the Indian army entered Bangladesh, engaged Pakistani military forces with the help of the Mukhti Bahini, and in a ten-day period subdued the Pakistani forces. On 16 December the Pakistani military surrendered. In January 1972, Mujib was released from confinement and became the prime minister of Bangladesh.

Bangladesh was founded as a "democratic, secular, socialist state," but the new state represented the triumph of a Bangladeshi Muslim culture and language. The administration degenerated into corruption, and Mujib attempted to create a one-party state. On 15 August 1975 he was assassinated, along with much of his family, by army officers. Since that time, Bangladesh has been both less socialistic and less secular.

General Ziaur Rahman became martial law administrator in December 1976 and president in 1977. On 30 May 1981, Zia was assassinated by army officers. His rule had been violent and repressive, but he had improved national economy. After a short-lived civilian government, a bloodless coup placed Army chief of staff General Mohammed Ershad in office as martial law administrator; he later became president. Civilian opposition increased, and the Awami League, the Bangladesh National Party (BNP), and the religious fundamentalist party Jamaat-i-Islami united in a seven-year series of crippling strikes. In December 1990, Ershad was forced to resign.

A caretaker government held national elections early in 1991. The BNP, headed by Khaleda Zia, widow of former President Zia, formed a government in an alliance with the Jamaat-i-Islami. Political factionalism intensified over the next five years, and on 23 June 1996, the Awami League took control of Parliament. At its head was Sheikh Hasina Wazed, the daughter of Sheikh Mujib.

National Identity. Bangladeshi national identity is rooted in a Bengali culture that transcends international borders and includes the area of Bangladesh itself and West Bengal, India. Symbolically, Bangladeshi identity is centered on the 1971 struggle for independence from Pakistan. During that struggle, the key elements of Bangladeshi identity coalesced around the importance of the Bengali mother tongue and the distinctiveness of a culture or way of life connected to the floodplains of the region. Since that time, national identity has become increasingly linked to Islamic symbols as opposed to the Hindu Bengali, a fact that serves to reinforce the difference between Hindu West Bengal and Islamic Bangladesh. Being Bangladeshi in some sense means feeling connected to the natural land–water systems of the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and other rivers that drain into the Bay of Bengal. There is an envisioning of nature and the annual cycle as intensely beautiful, as deep green paddy turns

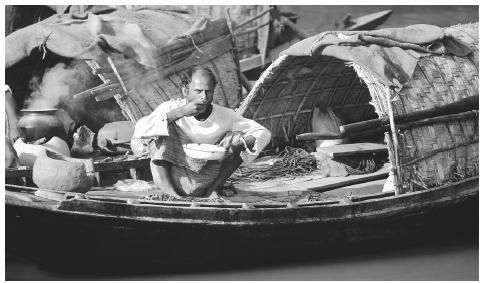

A man eating a meal on his houseboat in Sunderbans National Park. Fish and rice are a common part of the diet.

golden, dark clouds heavy with monsoon rains gradually clear, and flooded fields dry. Even urban families retain a sense of connectedness to this rural system. The great poets of the region, Rabindranath Tagore and Kazi Nurul Islam have enshrined the Bengali sense of the beauty and power of the region's nature.

Ethnic Relations. The most significant social divide is between Muslims and Hindus. In 1947 millions of Hindus moved west into West Bengal, while millions of Muslims moved east into the newly created East Pakistan. Violence occurred as the columns of people moved past each other. Today, in most sections of the country, Hindus and Muslims live peacefully in adjacent areas and are connected by their economic roles and structures. Both groups view themselves as members of the same culture.

From 1976 to 1998 there was sustained cultural conflict over the control of the southeastern Chittagong Hill Tracts. That area is home to a number of tribal groups that resisted the movement of Bangladeshi Muslims into their territory. In 1998, a peace accord granted those groups a degree of autonomy and self-governance. These tribal groups still do not identify themselves with the national culture.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

Bangladesh is still primarily a rural culture, and the gram or village is an important spatial and cultural concept even for residents of the major cities. Most people identify with a natal or ancestral village in the countryside.

Houses in villages are commonly rectangular, and are dried mud, bamboo, or red brick structures with thatch roofs. Many are built on top of earthen or wooden platforms to keep them above the flood line. Houses have little interior decoration, and wall space is reserved for storage. Furniture is minimal, often consisting only of low stools. People sleep on thin bamboo mats. Houses have verandas in the front, and much of daily life takes place under their eaves rather than indoors. A separate smaller mud or bamboo structure serves as a kitchen ( rana ghor ), but during the dry season many women construct hearths and cook in the household courtyard. Rural houses are simple and functional, but are not generally considered aesthetic showcases.

The village household is a patrilineal extended compound linked to a pond used for daily household needs, a nearby river that provides fish, trees that provide fruit (mango and jackfruit especially), and rice fields. The village and the household not only embody important natural motifs but serve as the locus of ancestral family identity. Urban dwellers try to make at least one trip per year to "their village."

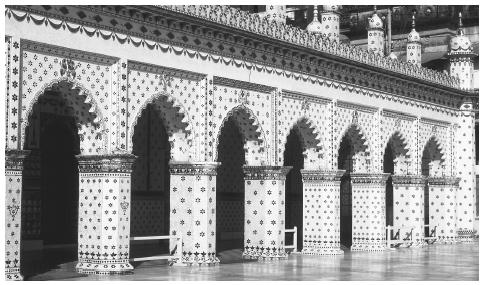

Architectural styles in the cities show numerous historical influences, including Moghul and Islamic motifs with curved arches, windows, and minarets, and square British colonial wood and concrete construction. The National Parliament building (Shongshad Bhabon) in Dhaka, designed by the American architect Louis Kahn, reflects a synthesis of western modernity and curved Islamic-influenced spaces. The National Monument in Savar, a wide-based spire that becomes narrower as it rises, is the symbol of the country's liberation.

Because of the population density, space is at a premium. People of the same sex interact closely, and touching is common. On public transportation strangers often are pressed together for long periods. In public spaces, women are constrained in their movements and they rarely enter the public sphere unaccompanied. Men are much more free in their movement. The rules regarding the gender differential in the use of public space are less closely adhered to in urban areas than in rural areas.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Rice and fish are the foundation of the diet; a day without a meal with rice is nearly inconceivable. Fish, meats, poultry, and vegetables are cooked in spicy curry ( torkari ) sauces that incorporate cumin, coriander, cloves, cinnamon, garlic, and other spices. Muslims do not consume pork and Hindus do not consume beef. Increasingly common is the preparation of ruti, a whole wheat circular flatbread, in the morning, which is eaten with curries from the night before. Also important to the diet is dal, a thin soup based on ground lentils, chickpeas, or other legumes that is poured over rice. A sweet homemade yogurt commonly finishes a meal. A typical meal consists of a large bowl of rice to which is added small portions of fish and vegetable curries. Breakfast is the meal that varies the most, being rice- or bread-based. A favorite breakfast dish is panthabhat, leftover cold rice in water or milk mixed with gur (date palm sugar). Food is eaten with the right hand by mixing the curry into the rice and then gathering portions with the fingertips. In city restaurants that cater to foreigners, people may use silverware.

Three meals are consumed daily. Water is the most common beverage. Before the meal, the right hand is washed with water above the eating bowl. With the clean knuckles of the right hand the interior of the bowl is rubbed, the water is discarded, and the bowl is filled with food. After the meal, one washes the right hand again, holding it over the emptied bowl.

Snacks include fruits such as banana, mango, and jackfruit, as well as puffed rice and small fried food items. For many men, especially in urbanized regions and bazaars, no day is complete without a cup of sweet tea with milk at a small tea stall, sometimes accompanied by confections.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. At weddings and on important holidays, food plays an important role. At holiday or formal functions, guests are encouraged to eat to their capacity. At weddings, a common food is biryani, a rice dish with lamb or beef and a blend of spices, particularly saffron. On special occasions, the rice used is one of the finer, thinner-grained types. If biryani is not eaten, a complete multicourse meal is served: foods are brought out sequentially and added to one's rice bowl after the previous course is finished. A complete dinner may include chicken, fish, vegetable, goat, or beef curries and dal. The final bit of rice is finished with yogurt ( doi ).

On other important occasions, such as the Eid holidays, a goat or cow is slaughtered on the premises and curries are prepared from the fresh meat. Some of the meat is given to relatives and to the poor.

Basic Economy. With a per capita gross national product (GNP) of $350 and an overall GNP of $44 billion, Bangladesh is one of the poorest countries in the world. The only significant natural resource is natural gas.

Approximately 75 percent of the workforce is involved in agriculture, and 15 percent and 10 percent are employed in the service and industrial sectors, respectively. Bangladesh has been characterized as a nation of small, subsistence-based farmers, and nearly all people in rural areas are involved in the production or processing of agricultural goods. The majority of the rural population engages in agricultural production, primarily of rice, jute, pulses, wheat, and some vegetables. Virtually all agricultural output is consumed within the country, and grain must be imported. The large population places heavy demands on the food-producing sectors of the economy. The majority of the labor involved in food production is human- and animal-based. Relatively little agricultural export takes place.

A Bangladeshi man hanging fish to dry in the sun in Sunderbans. Bangladesh topography is predominantly a low-lying floodplain.

In the countryside, typically about ten villages are linked in a market system that centers on a bazaar occurring at least once per week. On bazaar days, villagers bring in agricultural produce or crafts such as water pots to sell to town and city agents. Farmers then visit kiosks to purchase spices, kerosene, soap, vegetables or fish, and salt.

Land Tenure and Property. With a population density of more than two thousand per square mile, land tenure and property rights are critical aspects of survival. The average farm owner has less than three acres of land divided into a number of small plots scattered in different directions from the household. Property is sold only in cases of family emergency, since agricultural land is the primary means of survival. Ordinarily, among Muslims land is inherited equally by a household head's sons, despite Islamic laws that specify shares for daughters and wives. Among Hindu farmers inheritance practices are similar. When agricultural land is partitioned, each plot is divided among a man's sons, ensuring that each one has a geographically dispersed holding. The only sections of rural areas that are not privately owned are rivers and paths.

Commercial Activities. In rural areas Hindus perform much of the traditional craft production of items for everyday life; caste groups include weavers, potters, iron and gold smiths, and carpenters. Some of these groups have been greatly reduced in number, particularly weavers, who have been replaced by ready-made clothing produced primarily in Dhaka.

Agriculture accounts for 25 percent of GDP. The major crops are rice, jute, wheat, tea, sugarcane, and vegetables.

Major Industries. In recent years industrial growth has occurred primarily in the garment and textile industries. Jute processing and jute product fabrication remain major industries. Overall, industry accounted for about 28 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 1998.

Trade. Exports totaled $4.4 billion in 1996, with the United States consuming one-third of those exports. Primary export markets are for jute (used in carpet backing, burlap, and rope), fish, garments, and textiles. Imports totaled $7.1 billion and largely consisted of capital goods, grains, petroleum, and chemicals. The country relies on an annual inflow of at least $1 billion from international sources, not including the humanitarian aid that is part of the national economic system. Agriculture accounted for about 25 percent of the GDP in 1998.

Transporting straw on the Ganges River Delta. The majority of Bangladeshi, about 75 percent, are agricultural workers.

Division of Labor. The division of labor is based on age and education. Young children are economically productive in rural areas, hauling water, watching animals, and helping with postharvest processing. The primary agricultural tasks, however, are performed by men. Education allows an individual to seek employment outside the agricultural sector, although the opportunities for educated young men in rural areas are extremely limited. A service or industry job often goes to the individual who can offer the highest bribe to company officials.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. The Muslim class system is similar to a caste structure. The ashraf is a small upperclass of old-money descendants of early Muslim officials and merchants whose roots are in Afghanistan, Turkey, and Iran. Some ashraf families trace their lineage to the Prophet Mohammed. The rest of the population is conceived of as the indigenous majority atraf. This distinction mirrors the Hindu separation between the Brahman and those in lower castes. While both Muslim and Hindu categories are recognized by educated people, the vast majority of citizens envision class in a more localized, rural context.

In rural areas, class is linked to the amount of land owned, occupation, and education. A landowner with more than five acres is at the top of the socioeconomic scale, and small subsistence farmers are in the middle. At the bottom of the scale are the landless rural households that account for about 30 percent of the rural population. Landowning status reflects socioeconomic class position in rural areas, although occupation and education also play a role. The most highly educated people hold positions requiring literacy and mathematical skills, such as in banks and government offices, and are generally accorded a higher status than are farmers. Small businessmen may earn as much as those who have jobs requiring an education but have a lower social status.

Hindu castes also play a role in the rural economy. Hindu groups are involved in the hereditary occupations that fill the economic niches that support a farming-based economy. Small numbers of higher caste groups have remained in the country, and some of those people are large landowners, businessmen, and service providers.

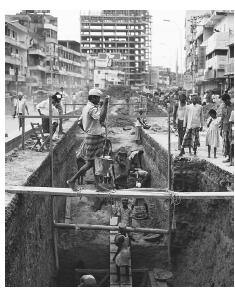

In urban areas the great majority of people are laborers. There is a middle class of small businessmen and midlevel office workers, and above this is an emerging entrepreneurial group and upper-level service workers.

Symbols of Social Stratification. One of the most obvious symbols of class status is dress. The traditional garment for men is the lungi, a cloth tube skirt that hangs to the ankles; for women, the sari is the norm. The lungi is worn by most men, except those who consider themselves to have high socioeconomic status, among whom pants and shirt are worn. Also indicative of high standing are loose white cotton pajama pants and a long white shirt. White dress among men symbolizes an occupation that does not require physical labor. A man with high standing will not be seen physically carrying anything; that task is left to an assistant or laborer. Saris also serve as class markers, with elaborate and finely worked cloth symbolizing high status. Poverty is marked by the cheap, rough green or indigo cotton cloth saris of poor women. Gold jewelry indicates a high social standing among women.

A concrete-faced house and a ceramic tile roof provide evidence of wealth. An automobile is well beyond the means of most people, and a motorcycle is a sign of status. Color televisions, telephones, and electricity are other symbols associated with wealth.

Political Life

Government. The People's Republic of Bangladesh is a parliamentary democracy that includes a president, a prime minister, and a unicameral parliament ( Jayitya Shongshod ). Three hundred members of parliament are elected to the 330-seat legislature in local elections held every five years. Thirty seats are reserved for women members of parliament. The prime minister, who is appointed by the president, must have the support of a majority of parliament members. The president is elected by the parliament every five years to that largely ceremonial post. The country is divided into four divisions, twenty districts, subdistricts, union parishads, and villages. In local politics, the most important political level is the union in rural areas; in urban regions, it is the municipality ( pourashava ). Members are elected locally, and campaigning is extremely competitive.

Leadership and Political Officials. There are more than 50 political parties. Party adherence extends from the national level down to the village, where factions with links to the national parties vie for local control and help solve local disputes. Leaders at the local level are socioeconomically well-off individuals who gain respect within the party structure, are charismatic, and have strong kinship ties. Local leaders draw and maintain supporters, particularly at election time, by offering tangible, relatively small rewards.

The dominant political parties are the Awami League (AL), the BNP, the Jatiya Party (JP), and the Jamaat-i-Islami (JI). The Awami League is a secular-oriented, formerly socialist-leaning party. It is not stringently anti-India, is fairly liberal with regard to ethnic and religious groups, and supports a free-market economy. The BNP, headed by former Prime Minister Khaleda Zia, is less secular, more explicitly Islamic in orientation, and more anti-India. The JP is close to the BNP in overall orientation, but pushed through a bill in Parliament that made Islam the state religion in 1988. The JI emphasizes Islam, Koranic law, and connections to the Arab Middle East.

Social Problems and Control. Legal procedures are based on the English common-law system, and supreme court justices and lower-level judges are appointed by the president. District courts at the district capitals are the closest formal venues for legal proceedings arising from local disputes. There are police forces only in the cities and towns. When there is a severe conflict or crime in rural areas, it may take days for the police to arrive.

In rural areas, a great deal of social control takes place informally. When a criminal is caught, justice may be apportioned locally. In the case of minor theft, a thief may be beaten by a crowd. In serious disputes between families, heads of the involved kinship groups or local political leaders negotiate and the offending party is required to make restitution in money and/or land. Police may be paid to ensure that they do not investigate. Nonviolent disputes over property or rights may be decided through village councils ( panchayat ) headed by the most respected heads of the strongest kinship groups. When mediation or negotiation fails, the police may be called in and formal legal proceedings may begin. People do not conceive of the informal procedures as taking the law into their own hands.

Military Activity. The military has played an active role in the development of the political structure and climate of the country since its inception and has been a source of structure during crises. It has been involved in two coups since 1971. The only real conflict the army has encountered was sporadic fighting with the Shakti Bahini in the Chittagong Hill Tracts from the mid-1970s until 1998, after which an accord between the government and those tribal groups was produced.

Road workers undertake construction work in Decca. Laborers make up the vast majority of workers in urban areas.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

Bangladesh is awash in social change programs sponsored by international organizations such as the United Nations, the World Bank, Care, USAID, and other nations' development agencies. Those organizations support project areas such as population control, agricultural and economic development, urban poverty, environmental conservation, and women's economic development.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

The Grameen Bank created the popular microcredit practice, which has given the poor, especially poor women, access to credit. This model is based on creating small circles of people who know and can influence each other to pay back loans. When one member has repaid a loan, another member of the group becomes eligible to receive credit. Other nongovernmental organizations include the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee, Probashi, and Aat Din.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. Women traditionally are in charge of household affairs and are not encouraged to move outside the immediate neighborhood unaccompanied. Thus, most women's economic and social lives revolve around the home, children, and family. Islamic practice reserves prayer inside the mosque for males only; women practice religion within the home. Bangladesh has had two female prime ministers since 1991, both elected with widespread popular support, but women are not generally publicly active in politics.

Men are expected to be the heads of their households and to work outside the home. Men often do the majority of the shopping, since that requires interaction in crowded markets. Men spend a lot of time socializing with other men outside the home.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. The society is patriarchal in nearly every area of life, although some women have achieved significant positions of political power at the national level. For ordinary women, movement is confined, education is stressed less than it is for men, and authority is reserved for a woman's father, older brother, and husband.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Marriage is almost always an arranged affair and takes place when the parents, particularly the father, decide that a child should be married. Men marry typically around age twenty-five or older, and women marry between ages fifteen and twenty; thus the husband is usually at least ten years older than the wife. Muslims allow polygynous marriage, but its occurrence is rare and is dependent on a man's ability to support multiple households.

A parent who decides that a child is ready to marry may contact agencies, go-betweens, relatives, and friends to find an appropriate mate. Of immediate concern are the status and characteristics of the potential in-law's family. Generally an equal match is sought in terms of family economic status, educational background, and piousness. A father may allow his child to choose among five or six potential mates, providing the child with the relevant data on each candidate. It is customary for the child to rule out clearly unacceptable candidates, leaving a slate of candidates from which the father can choose. An arrangement between two families may be sealed with an agreement on a dowry and the types of gifts to be made to the groom. Among

The Sitara (star) mosque in Dacca. Religion plays a fundamental role in society, and almost every village has a mosque.

the educated the dowry practice is no longer prevalent.

Divorce is a source of social stigma. A Muslim man may initiate a divorce by stating "I divorce you" three times, but very strong family pressure ordinarily ensures that divorces do not occur. A divorce can be most difficult for the woman, who must return to her parent's household.

Domestic Unit. The most common unit is the patrilineally-related extended family living in a household called a barhi. A barhi is composed of a husband and wife, their unmarried children, and their adult sons with their wives and children. Grandparents also may be present, as well as patrilineally-related brothers, cousins, nieces, and nephews. The oldest man is the authority figure, although the oldest woman may exert considerable authority within the household. A barhi in rural areas is composed of three or four houses which face each other to form a square courtyard in which common tasks are done. Food supplies often are shared, and young couples must contribute their earnings to the household head. Cooking, however, often is done within the constituent nuclear family units.

Inheritance. Islamic inheritance rules specify that a daughter should receive one-half the share of a son. However, this practice is rarely followed, and upon a household head's death, property is divided equally among his sons. Daughters may receive produce and gifts from their brothers when they visit as "compensation" for their lack of an inheritance. A widow may receive a share of her husband's property, but this is rare. Sons, however, are custom-bound to care for their mothers, who retain significant power over the rest of the household.

Kin Groups. The patrilineal descent principle is important, and the lineage is very often localized within a geographic neighborhood in which it constitutes a majority. Lineage members can be called on in times of financial crisis, particularly when support is needed to settle local disputes. Lineages do not meet regularly or control group resources.

Socialization

Infant Care. Most women give birth in their natal households, to which they return when childbirth is near. A husband is sent a message when the child is born. Five or seven days after the birth the husband and his close male relatives visit the newborn, and a feast and ritual haircutting take place. The newborn is given an amulet that is tied around the waist, its eye sockets may be blackened with soot or makeup, and a small soot mark is applied to the infant's forehead and the sole of the foot for protection against spirits. Newborns and infants are seldom left unattended. Most infants are in constant contact with their mothers, other women, or the daughters in the household. Since almost all women breastfeed, infant and mother sleep within close reach. Infants' needs are attended to constantly; a crying baby is given attention immediately.

Child Rearing and Education. Children are raised within the extended family and learn early that individual desires are secondary to the needs of the family group. Following orders is expected on the basis of age; an adult or older child's commands must be obeyed as a sign of respect. Child care falls primarily to household women and their daughters. Boys have more latitude for movement outside the household.

Between ages five and ten, boys undergo a circumcision ( musulmani ), usually during the cool months. There is no comparable ritual for girls, and the menarche is not publicly marked.

Most children begin school at age five or six, and attendance tends to drop off as children become more productive within the household (female) and agricultural economy (male). About 75 percent of children attend primary school. The higher a family's socioeconomic status, the more likely it is for both boys and girls to finish their primary educations. Relatively few families can afford to send their children to college (about 17 percent), and even fewer children attend a university. Those who enter a university usually come from relatively well-off families. While school attendance drops off overall as the grades increase, females stop attending school earlier than do males.

Higher Education. Great value is placed on higher education, and those who have university degrees and professional qualifications are accorded high status. In rural areas the opportunities for individuals with such experience are limited; thus, most educated people are concentrated in urban areas.

Bangladesh has a number of excellent universities in its largest urban areas that offer both undergraduate through post-graduate degrees. The most prominent universities, most of which are state supported, include: Dhaka University, Rajshahi University, Chittagong University, Jahngirnagar University, Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, and Bangladesh Agricultural University. Competition for university admission is intense (especially at Dhaka University) and admission is dependent on scores received on high school examinations held annually, as in the British system

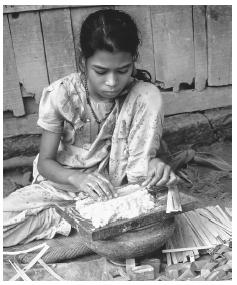

A young girl makes matchboxes in the slums of Khulna. There is a marked split between rich and poor in most of the country.

of education. University life in Bangladesh can be difficult. A four-year degree may actually require five to eight years to complete due to frequent university closings. The student bodies and faculties of universities are heavily politicized along national political party lines. Protests, strikes, and sporadic political party-based violence are common, as student groups play out national political agendas on their campuses and vie for members. Virtually every university student finds it easier to survive the system by becoming a member of the student wing of a political party.

While the universities are the scenes of political struggle, they are also centers of intellectual and cultural creativity. Students may obtain excellent training in all fields, including the arts, law, medicine, and engineering. Universities are also somewhat like islands where some of the ordinary rules of social interaction are relaxed. For example, male– female interaction on campuses is more open and less monitored than in society as a whole. Dance and theater presentations are common, as are academic debates.

Etiquette

Personal interaction is initiated with the greeting Assalam Waleykum ("peace be with you"), to which the required response is, Waleykum Assalam ("and with you"). Among Hindus, the correct greeting is Nomoshkar, as the hands are brought together under the chin. Men may shake hands if they are of equal status but do not grasp hands firmly. Respect is expressed after a handshake by placing the right hand over the heart. Men and women do not shake hands with each other. In same-sex conversation, touching is common and individuals may stand or sit very close. The closer individuals are in terms of status, the closer their spatial interaction is. Leave-taking is sealed with the phrase Khoda Hafez.

Differences in age and status are marked through language conventions. Individuals with higher status are not addressed by personal name; instead, a title or kinship term is used.

Visitors are always asked to sit, and if no chairs are available, a low stool or a bamboo mat is provided. It is considered improper for a visitor to sit on the floor or ground. It is incumbent on the host to offer guests something to eat.

In crowded public places that provide services, such as train stations, the post office, or bazaars, queuing is not practiced and receiving service is dependent on pushing and maintaining one's place within the throng. Open staring is not considered impolite.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. The symbols and sounds of Islam, such as the call to prayer, punctuate daily life. Bangladeshis conceptualize themselves and others fundamentally through their religious heritage. For example, the nationality of foreigners is considered secondary to their religious identity.

Islam is a part of everyday life in all parts of the country, and nearly every village has at least a small mosque and an imam (cleric). Prayer is supposed to be performed five times daily, but only the committed uphold that standard. Friday afternoon prayer is often the only time that mosques become crowded.

Throughout the country there is a belief in spirits that inhabit natural spaces such as trees, hollows, and riverbanks. These beliefs are derided by Islamic religious authorities.

Hinduism encompasses an array of deities, including Krishna, Ram, Durga, Kali, and Ganesh. Bangladeshi Hindus pay particular attention to the female goddess Durga, and rituals devoted to her are among the most widely celebrated.

Religious Practitioners. The imam is associated with a mosque and is an important person in both rural and urban society, leading a group of followers. The imam's power is based on his knowledge of the Koran and memorization of phrases in Arabic. Relatively few imams understand Arabic in the spoken or written form. An imam's power is based on his ability to persuade groups of men to act in conjunction with Islamic rules. In many villages the imam is believed to have access to the supernatural, with the ability to write charms that protect individuals from evil spirits, imbue liquids with holy healing properties, or ward off or reverse of bad luck.

Brahman priests perform rituals for the Hindu community during the major festivals when offerings are made but also in daily acts of worship. They are respected, but Hinduism does not have the codified hierarchical structure of Islam. Thus, a Brahman priest may not have a position of leadership outside his religious duties.

Rituals and Holy Places. The primary Islamic holidays in Bangladesh include: Eid-ul-Azha (the tenth day of the Muslim month Zilhaj ), in which a goat or cow is sacrificed in honor of Allah; Shob-i-Barat (the fourteenth or fifteenth day of Shaban ), when Allah records an individual's future for the rest of the year; Ramadan (the month Ramzan ), a month-long period of fasting between dawn and dusk; Eid-ul-Fitr (the first day of the month Shawal, following the end of Ramzan ), characterized by alms giving to the poor; and Shob-i-Meraz (the twenty-seventh day of Rajab ), which commemorates the night when Mohammed ascended to heaven. Islamic holidays are publicly celebrated in afternoon prayers at mosques and outdoor open areas, where many men assemble and move through their prayers in unison.

Among the most important Hindu celebrations are Saraswati Puja (February), dedicated to the deity Saraswati, who takes the form of a swan. She is the patron of learning, and propitiating her is important for students. Durga Puja (October) pays homage to the female warrior goddess Durga, who has ten arms, carries a sword, and rides a lion. After a nine-day festival, images of Durga and her associates are placed in a procession and set into a river. Kali Puja (November) is also called the Festival of Lights and honors Kali, a female deity who has the power to give and take away life. Candles are lit in and around homes.

A young Bengali woman performs a traditional Manipuri dance. Almost all traditional dancers are women.

Other Hindu and Islamic rituals are celebrated in villages and neighborhoods and are dependent on important family or local traditions. Celebrations take place at many local shrines and temples.

Death and the Afterlife. Muslims believe that after death the soul is judged and moves to heaven or hell. Funerals require that the body be washed, the nostrils and ears be plugged with cotton or cloth, and the body be wrapped in a white shroud. The body is buried or entombed in a brick or concrete structure. In Hinduism, reincarnation is expected and one's actions throughout life determine one's future lives. As the family mourns and close relatives shave their heads, the body is transported to the funeral ghat (bank along a river), where prayers are recited. The body is to be placed on a pyre and cremated, and the ashes are thrown into the river.

Medicine and Health Care

The pluralistic health care system includes healers such as physicians, nonprofessionally trained doctors, Aryuvedic practitioners, homeopaths, fakirs, and naturopaths. In rural areas, for non-life-threatening acute conditions, the type of healer consulted depends largely on local reputation. In many places, the patient consults a homeopath or a nonprofessional doctor who is familiar with local remedies as well as modern medical practices. Professional physicians are consulted by the educated and by those who have not received relief from other sources. Commonly, people pursue alternative treatments simultaneously, visiting a fakir for an amulet, an imam for blessed oil, and a physician for medicine.

A nationally run system of public hospitals provides free service. However, prescriptions and some medical supplies are the responsibility of patients and their families.

Aryuvedic beliefs based on humoral theories are common among both Hindus and Muslims. These beliefs are commonly expressed through the categorization of the inherent hot or cold properties of foods. An imbalance in hot or cold food intake is believed to lead to sickness. Health is restored when this imbalance is counteracted through dietary means.

Secular Celebrations

Ekushee (21 February), also called Shaheed Dibash, is the National Day of Martyrs commemorating those who died defending the Bangla language in 1952. Political speeches are held, and a memorial service takes place at the Shaheed Minar (Martyr's Monument) in Dhaka. Shadheenata Dibash, or Independence Day (26 March), marks the day when Bangladesh declared itself separate from Pakistan. The event is marked with military parades and political speeches. Poila Boishakh, the Bengali New Year, is celebrated on the first day of the month of Boishakh (generally in April). Poetry readings and musical events take place. May Day (1 May) celebrates labor and workers with speeches and cultural events. Bijoy Dibosh, or Victory Day (16 December), commemorates the day in 1971 when Pakistani forces surrendered to a joint Bangladeshi–Indian force. Cultural and political events are held.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. Artists are largely self-supporting. The Bangla Academy in Dhaka provides support for some artists, particularly writers and poets. Many artists sell aesthetic works that have utilitarian functions.

Literature. Most people, regardless of their degree of literacy, can recite more than one poem with dramatic inflection. Best known are the works of the two poet–heroes of the region: Rabindranath Tagore and Kazi Nurul Islam. Tagore was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913. Although from West Bengal, he is respected as a Bengali who championed the preservation of Bangla language and culture. His poem "Golden Bengal" was adopted as the national anthem.

The most famous contemporary writer is Taslima Nasreen, whose novellas and essays question the Islamic justification for the customary treatment of women. Conservative religious authorities have tried to have her arrested and have called for her death for blasphemy. She lives in exile.

Graphic Arts. Most graphic arts fall within the domain of traditional production by Hindu caste groups. The most pervasive art form throughout the country is pottery, including water jugs and bowls of red clay, often with a red slip and incising. Some Hindu sculptors produce brightly painted works depicting Durga and other deities. Drawing and painting are most visible on the backs of rickshaws and the wooden sides of trucks.

Performance Arts. Bengali music encompasses a number of traditions and mirrors some of the country's poetry. The most common instruments are the harmonium, the tabla, and the sitar. Generally, classical musicians are adept at the rhythms and melodic properties associated with Hindu and Urdu devotional music. More popular today are the secular male–female duets that accompany Bengali and Hindi films. These songs are rooted in the classical tradition but have a freer contemporary melodic structure. Traditional dance is characterized by a rural thematic element with particular hand, foot, and head movements. Dance is virtually a female-only enterprise. Plays are traditionally an important part of village life, and traveling shows stop throughout the countryside. Television dramas portray family relationships, love, and economic advantage and disadvantage. Plays in the cities, particularly in Dhaka, are attended by the educated young.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

Dhaka University offers courses in most academic disciplines. Sciences such as physics and chemistry have very good programs, although there is a lack of up-to-date laboratories and equipment. In the social sciences, the field of economics is particularly strong, along with anthropology, sociology, and political science. Many top students in the physical and social sciences study abroad, especially in the United States and Europe. The top engineering program is at the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology. Electrical, ocean/naval, civil, and mechanical engineering have very good programs. Education in computer engineering is improving rapidly.

Bibliography

Ahmed, Nafis. A New Economic Geography of Bangladesh, 1976.

Ali, A. M. M. Shawkat. Politics and Land System in Bangladesh, 1986.

Alim, A. Bangladesh Rice, 1982.

Baxter, Craig. New Nation in an Old Setting, 1984.

— Bangladesh: From a Nation to a State, 1997.

Bessaignet, Pierre. Tribesmen of the Chittagong Hill Tracts, 1958.

Blanchet, Therese. Women, Pollution, and Marginality, 1984.

Bornstein, David. The Price of a Dream: The Story of the Grameen Bank and the Idea That is Helping the Poor to Change Their Lives, 1997.

Chowdhury, Subrata Roy. The Genesis of Bangladesh: A Study in International Legal Norms and Permissive Conscience, 1972.

Glassie, Henry. Art and Life in Bangladesh, 1997.

Hartman, James, and Betsy Boyce. Needless Hunger, 1979.

Huq, Syed Mujibul, translator. Selected Poems of Kazi Nurul Islam, 1983.

Islam, Aminul A. K. M. Bangladesh Village: Political Conflict and Cohesion, 1982.

Majumdar, R. C. History of Bengal, 1943.

Nicholas, Marta, and Philip Oldenburg. Bangladesh: Birth of a Nation, 1972.

Novak, James J. Bangladesh: Reflections on the Water, 1993.

O'Donnell, Charles Peter. Bangladesh: Biography of a Muslim Nation, 1984.

Ray, Rajat Kanta. Mind, Body and Society: Life and Mentality in Colonial Bengal, 1995.

Sisson, Richard, and Leo Rose. War and Secession: Pakistan, India, and the Creation of Bangladesh, 1991.

United States Department of State. Bangladesh Background Notes, 1998.

Wennergren, E. Boyd, Charles H. Antholt, and Morris D. Whitaker. Agricultural Development in Bangladesh, 1984.

Wood, Geoffrey. Whose Ideas, Whose Interests?, 1991.