Culture of Armenia

Culture Name

Armenian

Alternative Names

Hayastan/Hayasdan; Haygagan/Haykakan/Haigagan; Haikakan

Orientation

Identification. The designation "Armenia" applies to different entities: a "historical" Armenia, the Armenian plateau, the 1918–1920 U.S. State Department map of an Armenia, and the current republic of Armenia. The notion "Armenian culture" implies not just the culture of Armenia but that of the Armenian people, the majority of whom live outside the current boundaries of the republic of Armenia.

Armenians call themselves hay and identify their homeland not by the term "Armenia" but as Hayastan or Hayasdan. The origins of these words can be traced to the Hittites, among whose historical documents is a reference to the Hayasa. In the Bible, the area designated as Armenia is referred to as Ararat, which the Assyrians referred to as Urartu. Armenians also identify themselves as the people of Ararat/Urartu and of Nairi, and their habitat as nairian ashkharh or yergir nairian . Armenians have called themselves Torkomian or Torgomian . They also call themselves Haigi serount or Haiki seround , descendants of Haig/Haik.

Location and Geography. Armenia has been identified with the mountainous Armenian plateau since pre-Roman times. The plateau is bordered on the east by Iran, on the west by Asia Minor, on the north by the Transcaucasian plains, and on the south by the Mesopotamian plains. The plateau consists of a complex set of mountain ranges, volcanic peaks, valleys, lakes, and rivers. It is also the main water reservoir of the Middle East, as two great rivers—the Euphrates and the Tigris— originate in its high mountains. The mean altitude of the Armenian plateau is 5,600 feet (1,700 meter) above sea level.

Present-day Armenia—the republic of Armenia—is a small mountainous republic that gained its independence in 1991, after seven decades of Soviet rule. It constitutes one-tenth of the historical Armenian plateau. Surrounding Lake Sevan, it has an area of approximately 11,600 square miles (30,000 square kilometers). Its border countries are Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan-Naxçivan, the Republic of Georgia, Iran, and Turkey. Its climate is highland continental, with hot summers and cold winters. Despite its small size, it was one of the most densely populated republics of the Soviet Union. Half of its inhabitants live in the Ararat plain, which constitutes only 10 percent of its territory and includes the capital city of Yerevan. Yerevan houses one-third of the country's population.

Armenia is a rugged, volcanic country with rich mineral resources. It is highly prone to earthquakes and occasional droughts.

Demography. Approximately 3 million people live in the republic of Armenia. Another 3 million Armenians live in various countries of the ex-Soviet Union—mainly in Russia. One and a half million Armenians are dispersed in the Americas. About one million Armenians live in various European countries, and half a million Armenians live in the Middle East and Africa. The ethnic composition of Armenia's population is 93.3 percent Armenian; 1.5 percent Russian; 1.7 percent Kurdish; and 3.5 percent Assyrian, Greek, and other.

Linguistic Affiliation. Armenian is the official language. When Armenia was under Russian and Soviet rule, Russian constituted the second official language. The Armenian language is an Indo-European language. Its alphabet was invented by the monk Mesrob in 406 C.E. . There are two major standardized versions of Armenian: Western Armenian,

Armenia

which was based on a version of nineteenth century Armenian spoken in Istanbul and is used mainly in the Diaspora, and Eastern Armenian, which was based on the Armenian spoken in Yerevan and is used in the ex-Soviet countries and Iran. This latter dialect was subjected to orthographic reforms during the Soviet era. There is also "Grabar" Armenian, the original written language, which is still used in the liturgy of the Armenian national (Apostolic) church.

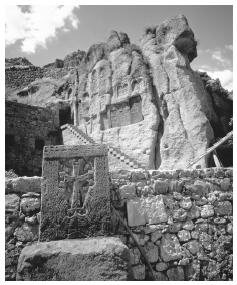

Symbolism. Mount Ararat has had symbolic significance for all Armenians. Today it lies outside the boundaries of Armenia. It may be seen on the horizon from Yerevan, but like a mirage it remains inaccessible to Armenians. Ancient manuscripts depicting the history of Armenia are housed in the national library, Madenataran, and are valued national and historical treasures. Particularly significant symbols of Armenian culture include the statue of Mother Armenia; Dsidsernagabert, a shrine with an ever-burning fire in memory of the Armenian victims of the 1915 genocide; the ruined ancient monasteries; khatchkars engraved stone burial crosses; the ruins of Ani, the last capital of historic Armenia, which fell in 1045; and the emblem of the 1918 first republic of Armenia, its tricolor flag.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of The Nation. Many prehistoric sites have been unearthed in and around Armenia, showing the existence of civilizations with advanced notions in agriculture, metallurgy, and industrial production, with diverse standardized manufacturing processes and pottery.

The origins of the Armenians have long been subject to debate among historians, linguists, and archaeologists. In the 1980s, linguists drew attention to the existence of many similarities between the Indo-European and Semitic languages. The only way to explain the linguistic similarities between these two linguistic groups would be to geographically move the cradle of the Indo-European linguistic groups farther east, to the Armenian plateau.

The Armenians and their plateau have been subject to various invasions. They witnessed Alexander the Great's expeditions toward the east. They fought the Roman legions and the Sassanid Persians, and in most cases lost. They stopped the Arabian expansion toward the north and provided emperors to the Byzantine throne. Having lost their own kingdom in the eleventh century to the invading Tartars and Seljuks, they managed to create a new kingdom farther south and west, in Cilicia, that flourished until 1375, playing a significant role during the Crusades. Then, they lost their last monarchy to the emerging Ottoman Empire, after the latter's westward expansion was stopped at the gates of Vienna. For more than two centuries, Armenia was devastated by the wars between two empires: the Iranian and the Ottoman. Starting at the end of the eighteenth century, the Russian empire also gained a foothold south of the Caucasus Mountains, defeating the Iranians and the Ottomans in a series of wars. The Armenian plateau thus became subject to the advances of three empires.

At the onset of the twentieth century, historical Armenia was divided between the Russian and the Ottoman (Turkish) Empires. Starting in the 1890s, periodical massacres of Armenians were organized by the Turkish authorities, which culminated in the genocide of 1915–1923. The Young Turk leadership of the Ottoman Empire, which had come to power

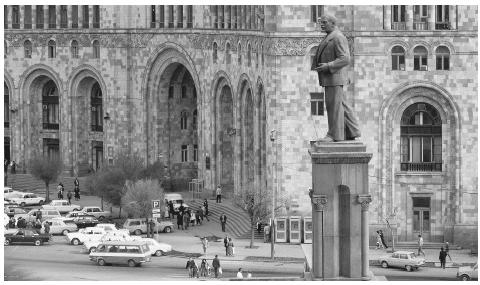

A statue of Russian Communist leader Vladimir Lenin in a square in Yerevan. Armenia was under Soviet rule from 1920 through 1990.

in 1908, seized the opportunity of World War I to physically remove the Armenian population. They envisioned a new Turkish nation-state (Turan), based on a monoethnic and monoreligious society, extending from Istanbul to Lake Baykal (in Central Asia). The entire Armenian population living under Turkish rule was thus subjected to systematic annihilation and the survivors scattered through the world in the aftermath of what would be known later as the first documented genocide of the twentieth century. Estimates of the Armenian dead vary from six hundred thousand to 2 million. A report of a United Nations human rights subcommission gave the figure of "at least one million."

In late 1917 the Russian empire collapsed and its armies withdrew from the Caucasus front. Eastern or Russian Armenia was left unprotected and by the spring of the next year, the Turkish army was advancing toward the east, trying to reach the oil fields of Baku, on the Caspian Sea. Only a last-ditch effort at the gates of Yerevan saved the Armenians of the east (in Russian Armenia) from the fate of their western compatriots (in Turkey). After the victorious battles of Sardarapat and Bash-Aparan, the Turkish onslaught was contained and reversed, and Armenia declared its independence on 28 May 1918.

Independence, however, was short-lived. After two years, due to the increasing pressure of, on the one hand, advancing Kemalist Turkish forces, and on the other, the Bolsheviks, the small landlocked republic of Armenia was forced to sign treaties that led to the loss of its territories and to its becoming a Soviet republic. Soviet rule lasted seventy years.

Having essentially followed the same path as most other nations under Soviet rule, the Armenians welcomed the dawn of the glasnost era, proclaimed by the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, as a means to correct the decades-old injustices imposed upon them.

Armenians believed in glasnost, and framed their demands in its rhetoric. In February 1988 there were impressive demonstrations in Yerevan and Stepanakert (the capital of Nagorno-Karabakh, an Armenian enclave in Azerbaijan) requesting the reunification of Karabakh with Armenia on the basis of self-determination rights. Following these demonstrations, on 28 May 1988, the seventeenth anniversary of the independence of Armenia was celebrated for the first time since Soviet rule. During the summer of 1988, mass demonstrations continued, followed by general strikes. In November 1988, Armenians were subjected to further massacres in Azerbaijan, leading to massive refugee problems. Emergency measures were established in both republics and Azerbaijan began a blockade of Armenia. The disastrous earthquake in Armenia on 7 December 1988 added to the existing refugee and economic problems. On 12 January 1989, a special commission to administer the Karabakh region, under the direct control of Moscow, was established. On 28 May 1989, the Soviet Armenian government recognized 28 May as the official anniversary of the republic of Armenia. During the summer of 1989, the Armenian National Movement acquired legal status, and held its first congress in November 1989. In January 1990, further Armenian massacres were reported in Baku and Kirovabad. During the spring elections, members of the Karabakh Committee, Soviet dissidents, came to power in parliamentary elections. The republic of Armenia gained its independence on 21 September 1991.

National Identity. The Armenian national identity is essentially a cultural one. From the historical depths of its culture and the dispersion of its bearers, it has acquired a richness and diversity rarely achieved within a single national entity, while keeping many fundamental elements that ensure its unity. Its bearers exhibit a strong sense of national identity that sometimes even clashes with the modern concept of the nation-state. It is an identity strongly influenced by the historical experiences of the Armenians. Events such as the adoption of Christianity as a state religion in 301 C.E. , the invention of the Armenian alphabet in 406 C.E. , and the excessively severe treatment at the hands of foreign powers at various times in its history have had a major impact.

Ethnic Relations. The republic of Armenia has thus far escaped the ethnic turmoil characterizing life in the post-Soviet republics. Minority rights are protected by law.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

The great majority of Armenians in Armenia and in the Diaspora are urbanites. In the republic of Armenia, 68 percent live in urban areas with a population density of 286 persons per square mile (110.5 per square kilometer).

Contemporary Armenian architecture has followed the basic characteristics of its historical architectural tradition: simplicity, reliance on locally available geological material, and the use of volcanic tufa for facings. During the Soviet era, however, prefabricated panels were used to build apartment

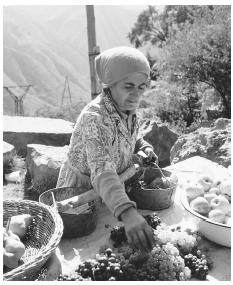

A woman sells fruit at a roadside stand. Armenia has focused on small-scale agriculture since gaining independence in 1991.

buildings, many of which collapsed during the 1988 earthquake.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Staple foods are bread and salt. Harissa a traditional meal, consists of wheat grain and lamb cooked over low heat. Armenians everywhere love barbecued meats and vegetables. The pomegranate, with its symbolic association with fertility, is the national fruit. Armenia is also vine and grape country. When speaking of friendship, Armenians say "we have bread and salt among us." In the state protocol, when dignitaries are welcomed, bread and salt are presented.

Breakfasts on nonworking days are sometimes major get-together events. In huge pots khash is prepared, cattle legs are boiled and served with spices and garlic and consumed with Armenian brandy.

Basic Economy. Since its independence from the Soviet Union, Armenia has been focusing on small-scale agriculture. In 1992, the state-run industries, including agriculture, were immediately privatized as Armenia adopted a Western-style economic system.

Major Industries. During Soviet rule, Armenia began to develop and concentrate on computer-based high technology, alongside a manufacturing sphere, the production of brandy, heavy industry, and mining. The 1991 blockade of the country by Azerbaijan led to a fuel shortage that often left its industries at a standstill. Nuclear energy was shut down after the 1988 earthquake as well, but production was resumed after a few years for lack of other reliable sources of energy. The current trend in industrial development is toward small volume/high-value products such as diamond cutting and electronic components, since transportation is still a major problem for the landlocked republic.

Trade. Armenia has been subject to an economic blockade since the early 1990s by its neighboring countries, with the exception of Iran and Georgia. Trade relations are newly developing. Armenia exports woven and knit apparel; beverages, including brandy; preserved fruits; art and handicrafts; books; precious stones; metals; and electrical machinery.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. For several centuries until the end of monarchic historical Armenia in 1045 and Cilicia in 1375, there were aristocratic noble houses with their respective court-related responsibilities. Afterwards, the notion of a generalized middle class emerged. Most Armenians were peasants until the turn of the twentieth century. During the Soviet era, class was de-emphasized. A new elite had emerged, however, based on the nomenclature or system that prevailed during Soviet rule.

Political Life

Government. The republic of Armenia is a democratic constitutional state. A constitution was adopted by national referendum in July 1995. Parliamentary elections were held in July 1995 and May 1999. Presidential elections were held in March 1998.

In 1999, fifteen parties and six political blocs took part in parliamentary elections.

Leadership and Political Officials. Robert Kocharian was the second president elected in the republic of Armenia since its independence. There is an elected national assembly ( Azgayin Joghov ), or parliament. The cabinet is formed by a prime minister designated by the president.

Social Problems and Control. During Soviet rule, Armenia had followed Soviet criminal and civil law. Since independence, a new autonomous legal system has been developing. The post independence period has also witnessed a rise in awareness in the media of organized crime and sex service rings.

Military Activity. Gradually, an autonomous army and defense system are being developed. Armenia joined the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) in March 1992 and signed the CIS Defense Treaty in May 1992.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

During the Soviet period, there was a well-established welfare system. Since then, the social welfare system has been affected by the economic crisis. Although the old age security system or pension is still in place, the amount of funding designated as monthly payment is not sufficient to maintain a subsistence living.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

The number of organizations registered as of 31 December 1998 broke down as follows: seventy-six political parties, 1,938 nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and 905 Media Outlets. The number of NGOs registered with the NGO Training and Resource Center totaled seven hundred.

Gender Roles and Statuses

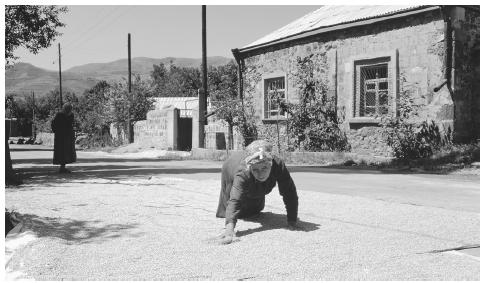

Division of Labor by Gender. Armenian culture has historically stressed a division of domains among the sexes. The home/household is a woman's domain. The grandmother/mother-in-law was the manager of the household. Women and men both worked outside the home. In the domestic sphere, women had no choice when it came to the chores. It was their duty and responsibility to maintain the household.

Women and men have equal access to all sectors of the economy. Nevertheless, only five banks, out of the total of 57, are managed by women. In terms of employment, there is a high rate of women's participation in the labor force. Also there is "equal pay for work of equal value." More women, however, are working in lower paid jobs. As a result, the average salary of women constitutes two thirds of men's salaries. The main work areas of women are in the sectors of education and health. The percentage of women working in industry is 40–42 percent. Women constitute 63.9 percent of unemployed workers. Women also account for most of

An Armenian woman drying grain beside the road in Garni Village, circa 1967. Historically, Armenian women were viewed as having responsibility for domestic chores and maintaining their households.

the domestic unpaid labor as well as for subsistence farming work.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. During the first republic of Armenia (1918–1920), women enjoyed equal voting and election rights. Four women were elected to the national parliament and one woman, Diana Apgar, became the ambassador to Japan. During the Soviet period, in spite of the legislation that stressed women's equality at all levels, women found it difficult to get into the higher decision-making processes. In 1991, during the first democratic elections in the newly independent republic of Armenia, women candidates won in only nine constituencies out of 240, representing only 3.6 percent of the parliament membership. None of the permanent parliamentary committees include any female members.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Armenians are monogamous. In some cases, marriages are arranged. The accepted practice is to avoid marriage with close kin (of up to seven kin-distances). Because of housing shortages in Soviet Armenia, the new couple resided with the groom's family (patrilocality). The preference, however, has been and continues to be for neolocality, that is, the new couple forming a new household.

Domestic Unit. The married couple and their offspring constitute the domestic unit. During Soviet rule, the domestic unit consisted of a multi generational family. Often paternal grandparents, their married offspring, and unmarried aunts and uncles resided together. In pre-Soviet times, each region had its own preference. The most common domestic unit, however, was a patrilocal multi generational family.

Inheritance. Although inheritance laws have undergone changes and reforms over the years, historically, men and women have been treated equally. Diaspora Armenian communities follow the inheritance laws of their respective countries.

Kin Groups. Kin relations are bilateral. Descent, however, is determined by the patrilineal line.

Socialization

Infant Care. Mothers are seen as the main providers of infant care. During Soviet rule, free infant day care was available to all, but Armenians preferred to leave their infants with grandmothers and

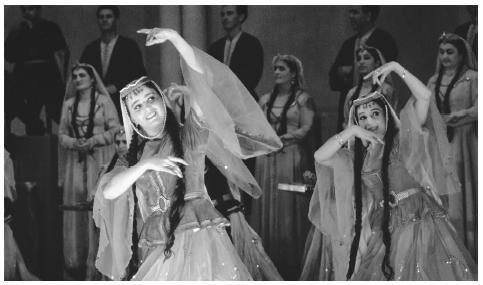

Armenian folk dancers in Yerevan. Armenia has a long tradition of musical art dating back to prehistoric times.

other close kin. Day-care workers were also mainly women. During the Soviet era, women were guaranteed their employment after a prolonged, paid maternity leave. The practice has continued after independence, pending new reforms, which observers fear may decrease paid maternity leave.

Child Rearing and Education. Women are considered to be the bearers and transmitters of culture, customs, and tradition and are seen as responsible for child rearing. Children are highly valued and they occupy the center of attention in households until they reach puberty. At puberty they are disciplined and are expected to take on responsibilities. Education is valued and is given great weight as an agent of socialization. In Armenia throughout the twentieth century, education was free and accessible to all. Because of privatization trends in the post reindependence period, however, there are fears that education may not remain accessible to all.

Higher Education. Armenia has stressed free access to education. A national policy directed at the elimination of illiteracy began in the first republic (1918–1920) and continued in Soviet times, resulting in a nearly 100 percent literacy rate. Women enjoy equal rights at all levels of education. A private higher education system was introduced in 1992. Although there is no discrimination on the basis of sex, some fields have become labeled "female." Of the students in the health-care field, 90 percent are women. In arts and education women constitute 78 percent of the students, in economics the number drops to 44.7 percent, for agriculture, 41 percent, and for industry, transportation, and communications, 40 percent.

Etiquette

Armenians put great emphasis on hospitality and generosity. There is also an emphasis on respect for guests.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Christianity has been the state religion in Armenia since 301. During Soviet rule, religious expression was not encouraged. The emphasis was on atheism. Armenians had continued to attend church, however, in particular for life-crisis events and rites of passage. The majority of Armenians adhere to the Armenian Apostolic Church. There are also adherents to Catholic, Evangelical, and Protestant denominations.

The church has been a symbol of national culture. It has been seen as the home of Armenians and the bearer of Armenian culture.

A temple cut into a Tufa rockface.

Religious Practitioners. The Armenian Apostolic Church has two catholicosate sees: the Catholicos of All Armenians at Etchmiadzin, Armenia, and Cilicia, in Antelias, Lebanon. The two sees are organized differently. Each has its own educational system and hierarchy of priests. Among the Armenians there are celibate and married priests. There are also two patriarchates: one in Istanbul and another in Jerusalem. Women are not ordained into priest-hood. There is only one women's order: the Kalfayian sisters.

Death and the Afterlife. Most Armenians believe in the Christian vision of death and afterlife. The Apostolic Church, unlike some Christian institutions, does not put emphasis on sin and redemption. Likewise the notion of purgatory is absent. Armenians pay special attention to remembering the dead. After every mass, or badarak , there is a memorial service for the dead. The seventh day after death, the fortieth day, and annual remembrance are the accepted way of respecting the dead. Cemeteries are well kept. The communion between the living and the dead is seen in the frequent visits to the graves of loved ones. Food and brandy are served to the dead. The birthdays of dead loved ones are also celebrated.

Medicine and Health Care

Western medical practices are followed in the health sector. Until recently, medicine and health care were universal and state run. The introduction of a private health sector has been discussed. There are already a number of private clinics operating in the republic of Armenia. In addition, a few clinics operate under the sponsorship of Diaspora voluntary associations, such as the Armenian General Benevolent Union and the Armenian Relief Society.

Secular Celebrations

New Year's Eve (or Amanor, Nor Dari, or Gaghant/Kaghand) is a secular holiday. Other secular holidays include: Women's Day 7 April; the commemoration of the 1915 genocide of the Armenians 24 April; the Independence day of the first Armenian republic of 1918, and 28 May; the Independence Day of the current republic of Armenia, 21 September.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. In the republic of Armenia, following the policies put forth during the pre-Soviet and Soviet eras, the state has been supporting the arts and humanities. In recent years, because of economic difficulties, there has been a privatization trend. State support is diminishing. In the Diaspora, the arts and humanities rely on local fund-raising efforts, Armenian organizations, and the initiative of individuals. In the republic of Armenia, artists are engaged full time in their respective arts. In the Diaspora, however, artists are rarely self-supporting and rarely make a living through their art.

Literature. Armenians have a rich history of oral and written literature. Parts of the early oral literature was recorded by M. Khorenatsi, a fourth-century historian. During the nineteenth century, under the influence of a European interest in folklore and oral literature, a new movement started that led to the collection of oral epic poems, songs, myths, and stories.

The written literature has been divided into five main epochs: the fifth century golden age, or vosgetar following the adoption of the alphabet; the Middle Ages; the Armenian Renaissance (in the nineteenth century); modern literature of Armenia and Constantinople (Istanbul) at the turn of the twentieth century; and contemporary literature of Armenia and the Diaspora. The fifth century has been recognized internationally as a highly productive epoch. It was also known for its translations of various works, including the Bible. In fact, the clergy have been the main producers of Armenian literary works. One of the most well-known early works is Gregory Narekatzi's Lamentations . During medieval times, a tradition of popular literature and poetry gradually emerged. By the nineteenth century, the vernacular of eastern (Russian and Iranian) Armenia became the literary language of the east, and the vernacular of Istanbul and western (Ottoman Turkish) Armenia became the basis of the literary rebirth for Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire.

Armenian literature has been influenced by European literary styles and movements. It also reflects the tragic history of its people. The 1915 genocide led to the death of the great majority of the Armenian writers of the time. The period immediately after the genocide was marked by a silence. Eventually there emerged a Diaspora literature with centers in Paris, Aleppo, and Beirut. In Soviet Armenia, the literary tradition followed the trends in Russia with a recognizable Armenian voice. Literature received the support of the Soviet state. A writers union was established. At the time of glasnost and perestroika, the emerging leaders belonged to the writers union.

Graphic Arts. Historically, Armenian art has been associated with architecture, bas-reliefs, stone engravings, steles, illuminated manuscripts, and tapestry. Since the Armenian Renaissance during the nineteenth century, interest in drawing, painting, sculpture, textiles, pottery, needlework, and lace has intensified. During the Soviet period, graphic arts were particularly encouraged. A new Armenian style of bright colors emerged in painting. An interest in landscape painting, rustic images, a focus on rural life, and ethnographic genre paintings were noticeable in Soviet Armenia. A national art gallery houses the works of Sarian, M. Avedissian, Hagopian, Soureniantz, and other artists of the Soviet epoch. In the current republic, there are outdoor exhibits of newly emerging painters, and new private initiatives are being made.

Performance Arts. Armenia has a long tradition of musical art, dating back to prehistoric times, and Armenian musicians played a fundamental role in the modernization of oriental music during the nineteenth century. Armenian traditional music differs from its oriental counterparts by its sobriety.

The republic of Armenia has thus far continued the trend set in Soviet years. The opera house, the theaters, and the concert halls are the pride of Armenians and have remained highly accessible to the general public. Armenian folk, classic, and religious music, as well as its composers, such as Komitas and A. Khatchadourian, have been known throughout the world. The folk-dance ensembles have also been participating in various international festivals.

The State of Physical and Social Sciences

In the republic of Armenia, as in Soviet Armenia, as well as in the Armenian republic of 1918, the state has been the main support system for the physical and social sciences. There is a well-established Academy of Sciences, where the social sciences and humanities have been and are represented. In recent years Armenia has been experiencing a dramatic financial crisis. The state is unable to continue its support of research and development. There have been calls for Diaspora fund-raising support. International foundations have also been approached to provide financing.

Bibliography

Alem, Jean-Pierre. Armenie. Paris , 3rd ed., 1972.

Aprahamian, S. "Armenian Identity: Memory, Ethnoscapes, Narratives of Belonging in the Context of the Recent Emerging Notions of Globalization and Its Effect on Time and Space." Feminist Studies in Aotearoa Journal 60 , 1999.

Armenia. National Report on the Conditions of Women , 1995.

Bauer-Manndorff, Elisabeth. Armenia, past and present. Translated by Frederick A. Leist, 1981.

Berndt, Jerry. Armenia: Portraits of Survival, 1994.

Bjorklund, Ulf. "Armenia Remembered and Remade: Evolving Issues in a Diaspora." Ethnos 58: 3-4, 335-360, 1993.

Cox, Caroline, and John Eibner. Ethnic Cleansing in Progress: War in Nagorno Karabakh, 1993.

Der Manuelian, Lucy, and Murray L. Eiland. Weavers, Merchants, and Kings: The Inscribed Rugs of Armenia. Edited by Emily J. Sano, 1984.

Der Nersessian, Sirarpie. The Armenians, 1969.

Hamalian, Arpi. The Armenians: Intermediaries for the European Trading Companies, 1976.

Hovannisian, Richard G. Armenia on the Road to Independence, 1918, 1967.

——. The Republic of Armenia. Berkeley: (In six volumes). 1971.

——, ed. The Armenian genocide in perspective, 1986.

——, ed. Remembrance and Denial: The Case of the Armenian Genocide, 1998.

Kasbarian, Lucine. Armenia: A Rugged Land, an Enduring People, 1998.

Kazandjian, Sirvart. Les origines de la musique Arménienne, 1984.

Khorenatsi, Moses. History of the Armenians. Translated by Robert W. Thomson, 1978.

Lang, David Marshall. Armenia: Cradle of Civilization, 1970.

——. The Armenians, a People in Exile, 1981.

Libaridian, J. Gerard, ed. Armenia at the Crossroads: Democracy and Nationhood in the Post-Soviet Era, 1991.

Lynch, H. F. B. Armenia, Travels and Studies, 2 vols., 1901.

Mandelstam, Osip. Journey to Armenia, Translated by Clarence Brown, 1980.

Marashlian, Levon. Politics and Demography: Armenians, Turks and Kurds in the Ottoman Empire, 1991.

Marsden, Philip. The Crossing Place: A Journey among the Armenians, 2nd ed., 1995.

Mouradian, Claire. De Staline à Gorbatchev: Histoire d'une republique sovietique: l'Arménie, 1990.

Nersessian, Vrej Nerses, comp. Armenia, 1993.

Oshagan, Vahe, special ed. Armenia, 1984.

Samuelian, Thomas J., ed. Classical Armenian Culture: Influences and Creativity, 1981.

——, and Michael E. Stone, eds. Medieval Armenian Culture, 1984.

Somakian, Manoug Joseph. Empires in Conflict: Armenia and the Great Powers, 1895-1920, 1995.

Tashjian, Nouvart. Armenian Lace, Edited by Jules and Kaethe Kliot, 1982.

Thierry, Jean-Michel. Armenian Art. Translated by Celestine Dars, 1989.

Toriguian, Shavarsh. The Armenian Question and International Law, 1973.

Utudjian, Edouard. Armenian Architecture, 4th to 17th century. Translated by Geoffrey Capner. 1968.

Vassilian, Hamo B., ed. The Armenians: A Colossal Bibliographic Guide to Books Published in the English Language, 1993.

Walker, Christopher J. Armenia, the Survival of a Nation, rev. ed., 1990.